Regulating Ayurvedic Medicine in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Assembly Official Records Fifty-Fourth Session

United Nations A/54/PV.19 General Assembly Official Records Fifty-fourth session 19th plenary meeting Thursday, 30 September 1999, 3 p.m. New York President: Mr. Gurirab ...................................... (Namibia) The meeting was called to order at 3.05 p.m. responsibilities, and are confident that this body will be well served in the months ahead. We shall cooperate with Address by Mr. Joaquim Alberto Chissano, President of you in every way we can. the Republic of Mozambique A well-deserved tribute is also due to your The President: The Assembly will first hear an predecessor, His Excellency Mr. Didier Opertti of address by the President of the Republic of Mozambique. Uruguay, for the exemplary manner in which he spearheaded the proceedings of the Organization during Mr. Joaquim Alberto Chissano, President of the the last session. Republic of Mozambique, was escorted into the General Assembly Hall. I would also like to express my high regard to the Secretary-General for his continued commitment to The President: On behalf of the General Assembly, international peace and security and for his leadership in I have the honour to welcome to the United Nations the dealing with an ever-increasing array of challenges President of the Republic of Mozambique, His Excellency worldwide. I wish to encourage him to continue on this Mr. Joaquim Alberto Chissano, and to invite him to address positive path. the Assembly. My Government welcomes the recent admission to President Chissano: On behalf of my Government the membership of the United Nations of the Republic of and on my own behalf, I wish to join previous speakers in Kiribati, the Republic of Nauru and the Kingdom of congratulating you, Sir, most sincerely on your election as Tonga. -

Chronology of Major Political Events in Contemporary Nepal

Chronology of major political events in contemporary Nepal 1846–1951 1962 Nepal is ruled by hereditary prime ministers from the Rana clan Mahendra introduces the Partyless Panchayat System under with Shah kings as figureheads. Prime Minister Padma Shamsher a new constitution which places the monarch at the apex of power. promulgates the country’s first constitution, the Government of Nepal The CPN separates into pro-Moscow and pro-Beijing factions, Act, in 1948 but it is never implemented. beginning the pattern of splits and mergers that has continued to the present. 1951 1963 An armed movement led by the Nepali Congress (NC) party, founded in India, ends Rana rule and restores the primacy of the Shah The 1854 Muluki Ain (Law of the Land) is replaced by the new monarchy. King Tribhuvan announces the election to a constituent Muluki Ain. The old Muluki Ain had stratified the society into a rigid assembly and introduces the Interim Government of Nepal Act 1951. caste hierarchy and regulated all social interactions. The most notable feature was in punishment – the lower one’s position in the hierarchy 1951–59 the higher the punishment for the same crime. Governments form and fall as political parties tussle among 1972 themselves and with an increasingly assertive palace. Tribhuvan’s son, Mahendra, ascends to the throne in 1955 and begins Following Mahendra’s death, Birendra becomes king. consolidating power. 1974 1959 A faction of the CPN announces the formation The first parliamentary election is held under the new Constitution of CPN–Fourth Congress. of the Kingdom of Nepal, drafted by the palace. -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR)

Nine Years On: The 1999 eLection and Nepalese politics since the 1990 janandoLan' John Whelpton Introduction In May 1999 Nepal held its th ird general election since the re-establishment of parliamentary democracy through the 'People's Movement' (janandolan) of spring 1990. it was in one way a return to the start ing point si nce, as in the first (1991) electio n, the Nepali Congress achieved an absolute majority, whilst the party's choice in 1999 for Prime Minister, Krishna Prasad Bhat tami, had led the \990-9\ interim government and would have conti nued in otTi ce had it not been for his personal defeat in Kathmandu-i constituency. Whilst the leading figu re was the same, the circumstances and expectations we re, of course, ve ry different. Set against the high hopes of 1990, the nine years of democracy in praclice had been a disill us ioning ex perience for mosl Ne palese, as cynical manoeuvring for power seemed to have replaced any attempt 10 solve the deep economic and social problems bequeathed by the Panchayat regime. This essay is an allempt to summarize developments up to the recent election, looking at wha t has apparently go ne wrong but also trying to identify some positive ac hievements.l The political kaleidoscope The interim government, which presided over the drafting of the 1990 I I am grateful 10 Krishna Hachhelhu for comments on an earlier draft oflhis paper and for help in collecting materials. 1 The main political developments up to late 1995 are covered in Brown (1996) and Hoftun et al. -

1990 Nepal R01769

Date Printed: 11/03/2008 JTS Box Number: lFES 8 Tab Number: 24 Document Title: 1991 Nepalese Elections: A Pre- Election Survey November 1990 Document Date: 1990 Document Country: Nepal lFES ID: R01769 • International Foundation for Electoral Systems 1620 I STREET. NW "SUITE 611 "WASHINGTON. D.c. 20006 "1202) 828·8507 • • • • • Team Members Mr. Lewis R. Macfarlane Professor Rei Shiratori • Dr. Richard Smolka Report Drafted by Lewis R. Macfarlane This report was mcuJe possible by a grant • from the U.S. Agency for International Development Any person or organization is welcome to quote information from this report if it is attributed to IFES. • • BOARD OF Patricia Hutar James M. Cannon Randal C. Teague FAX: 1202) 452{)804 DIRECTORS Secretary Counsel Charles T. Manatt F. Clihon White Robert C. Walker • Chairman Treasurer Richard M. Scammon • • Table of Contents Mission Statement ............................ .............. i • Executive Summary .. .................. ii Glossary of Terms ............... .. iv Historical Backgrmlnd ........................................... 1 History to 1972 ............................................ 1 • Modifications in the Panchayat System ...................... 3 Forces for Change. ........ 4 Transformation: Feburary-April 1990.... .................. 5 The Ouest for a New Constitution. .. 7 The Conduct of Elections in Nepal' Framework and PrQce~lres .... 10 Constitution: Basic Provisions. .................. 10 • The Parliament. .. ................. 10 Electoral Constituency and Delimitation Issues ........... -

Soil Microbial Biomass in Relation to Fine Root in Kiteni Hill Sal Forest of Ilam, Eastern Nepal

Nepalese Journal of Biosciences 2: 80-87 (2012) Soil microbial biomass in relation to fine root in Kiteni hill Sal forest of Ilam, eastern Nepal Krishna Prasad Bhattarai * and Tej Narayan Mandal Department of Botany, Post Graduate Campus, Tribhuvan University, Biratnagar, Nepal *E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Soil microbial biomass in relation to fine root was studied in Kiteni hill Sal (Shorea robusta ) forest of Ilam during summer season. The forest had sandy loam type of soil texture. Organic carbon was higher in 0-15 cm depth (2.09%) than in 15-30 cm depth (1.53%). Total nitrogen of 0- 15 cm depth was 0.173% and in 15-30 cm depth was 0.124%. Soil microbial biomass of carbon of Kiteni hill sal forest was (445.14 µg g -1) and microbial biomass of nitrogen was (49.07 µg g -1). Fine root biomass of this forest was 2.34 t ha -1 (<2 mm diameter) and 0.93 t ha -1 (2-5 mm diameter) in 0-15 cm depth and 0.73 t ha -1 (<2 mm diameter) and 0.46 t ha -1 (2-5 mm diameter) in 15-30 cm depth. Organic carbon, total nitrogen, soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen of upper layer soil were negatively correlated with fine root biomass of forest. Key words : Hill sal forest, physico-chemical properties, microbial biomass, fine root biomass, Ilam Introduction Hill sal ( Shorea robusta Gaertn. f.) forest is an important vegetation of upper tropical belt. It ranges from 300 to 1000 m altitude in the hilly region and extends from east to west of Nepal (Anonymous, 2002). -

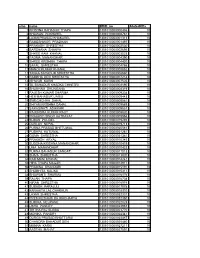

Garima Bikas Bank Limited

GARIMA BIKAS BANK LIMITED BONUS TAX RECEIVABLE (FY 2073/74) BONUS TAX S.N BOID FULL NAME Amount 1 1301170000182670 KRISHNA ARYAL 51,500.25 2 1301170000013818 KRISHNA PRASAD PANGENI 45,900.00 3 1301150000056438 CHET NARAYAN SHRESTHA 27,386.10 4 1301140000007224 RUDRA BAHADUR B K 25,500.00 5 1301150000056480 RABINDRA KUNWAR 25,428.75 6 1301090000056541 BABU RAM DHAKAL 25,245.75 7 1301150000056476 OM BAHADUR THAPA 22,650.00 8 1301590000002589 GHAN SHYAM GAUNDEL 22,500.00 9 1301170000026390 AMRIT BANIYA 18,750.00 10 1301150000056398 TULASI RAM TIWARI 15,300.00 11 1301160000003116 SABIN SHRESTHA 15,300.00 12 1301370000797335 RAJESH SUBEDI 15,000.00 13 1301120000497532 DIWAKAR PAUDEL 12,240.00 14 1301120000029970 BINAY REGMI 11,250.00 15 1301120000482868 DHRUBA RAJ SUBEDI 10,710.00 16 1301100000286691 PADAM PANI KAFLE 8,972.25 17 1301150000056495 RAM CHANDRA GURUNG 8,100.00 18 1301010000010666 BHARAT RAJ DHAKAL 7,686.09 RADHADEVI PAUDEL BHANNE YUDDHA 1301150000047653 7,650.75 19 KUMARI MALLA 20 1301080000127921 DIPAK SHARMA 7,650.00 21 1301170000166745 THAHAR BAHADUR BHANDARI 7,500.00 22 1301090000418467 SANGITA UPADHYAYA 7,500.00 23 1301060000370553 PARBATI ARYAL PARU 7,500.00 24 1301100000339734 JAGANNATH PANGENI 7,500.00 25 1301060001052452 LOK PRASAD ARYAL 7,500.00 26 1301060000188081 RAJENDRA LIGAL 6,788.25 27 1301370000029897 PURUSHOTTAM PARAJULI 6,000.00 28 1301120000031935 YEK NARAYAN SHARMA 4,835.25 29 1301070000208131 LEKHNATH CHAPAGAIN 4,698.00 30 1301070000309358 KOPILDEV ADHIKARI 4,698.00 31 1301070000038093 BABU RAM ADHIKARI 4,590.75 -

Nepalese Political Parties: 1987A

16 17 Berreman, Gerald D. 1962. Behind many Masks: Ethnography and Impression TOPICAL REPORT Management in a Himalayan Village. Monograph of the Society of Applied Anthropology; NoA. Also published in Berreman 1992. Nepalese Political Parties: 1987a. "Pahari Polyandry: A Comparison." In: M.K . Raha (ed.), Polyandry in India: Demographic. Economic. Social, Religious and Psychological Developments since the 1991 Elections Concomitants of Plural Marriages in Women. Delhi: Gian Publishing House, pp. 155-178. John Wbelpton 1987b. "HimaJayan Polyandry and the Domestic Cycle." In: M.K. Raha (ed.). Polyandry in India ( ... ), pp. 179-197. Based on a 'computer file updated regularly since 1990, this survey does not 1992. Hindus of the Himalayas: Ethnography and Change. Delhi, etc. : claim to be analytical but simply records some of the main developments in Oxford University Press. intra· and inter·party politics up to the recent (November 1994) general Bhall, O.S. and Jain, S.O. 1987. "Women's Role in a Polyandrous Cis-Hima1ayan election.! Infonnation has been drawn principally from the Nepal Press Digest, Society: An Overview." In: M.K. Raha (ed.). Polyandry in In dia ( ... ), pp. also from "Saptahik Bimarsha", Spotlight and other publications and from 405-421. interviews conducted in Kathmandu. Only brief mention has been made of the Brown. Charles W. and loshi, Maheshwar P. 1990. "Caste Dynamics and pre·1991 history of each party, including its role in the Movement for the Fluidity in the Historical Anthropology of Kumaon." In: M.P. loshi, A.C. Restoration of Democracy, and fuller details will be found in Whclplon 1993 and Fanger and C.W. -

Nepali Times on the Maoist Insurgency

#29 9 - 15 February 2001 20 pages Rs 20 EXCLUSIVE Dead Line It is turning out as everyone feared: BACK TO with three days to go for another hotel strike deadline there is no SUBHAS RAI compromise in sight. It’s not just a dispute about the 10 percent service charge anymore, it is now a question of the survival of the SQUARE ONE tourism industry and the nation’s economy itself. Arrivals are down BINOD○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ BHATTARAI and long-suffering Nepalis will have to by 11 percent, hotels are empty he country has now been held hostage to keep on paying the price for selfish and the economy is already feeling the ruling party infighting for nearly a politicians who can’t get along. the pinch. Everyone with a stake in tyear. There was hope that the ministerial Koirala’s house of cards began this dispute: hoteliers, hotel reshuffle this week would finally close that crumbling hours after the new employees, the government and chapter, but we underestimated the intensity appointments were announced on the mediators in the National of the competition among politicos for the Wednesday morning. By mid-day Planning Commission (NPC) juicy ministerial posts. Khum Bahadur Khadka, awarded the share the blame for playing politics That was the reason for the original plum Melamchi ministry (Physical Planning with the issue and for foot- infighting in October, and that is why Prime and Works), and Palten Gurung, given his dragging. Despite their posturing, Minister Girija Prasad Koirala’s efforts to pick, the labour and transport management hotel owners and workers both say soften dissidents by offering them cabinet portfolio, had come out with a statement that they want to resolve the issue. -

IIII ~I~ I~II~HI I~ E E - C a - 4 3 9 2 - B 1 6 I Ll:~ :S International Foundation for Electoral Systems I ------~------~ 1620 I STREET

Date Printed: 11/03/2008 JTS Box Number: IFES 8 Tab Number: 21 Document Title: Kingdom of Nepal: Parliamentary Elections Document Date: 1991 Document Country: Nepal lFES ID: R01771 II~ ~I~ ~ ~IIII ~I~ I~II~HI I~ E E - C A - 4 3 9 2 - B 1 6 I ll:~_:S International Foundation for Electoral Systems I ----------------------------------~---------------- ~ 1620 I STREET. NW.· SUITE 611 • WASHINGTON. DC 20006·12021828·8507. FAX 12021452·0804 I I I I . .r:', , ,~;~, I ,' .. -. ';', I . , z . , I . .. I United States Election Observer Report I I I I 80ARDOF r Clifton While Patrloa HUlar James M. Cannon Randal C Teague I DIRECTORS Chcmman Secretary Counsel Richard M Scammon Charles Manan Jo.'1n C. White RIChard W Soudnerre ROben C Walker I Vice Chairman Treasurer Drrector I , r.:.. _:.,.- .'.~ ;J International Foundation for Electoral Systems I r:fJ;I Q. --------"---- U)~. 1620 I STREET. NW • SUITE 611 • WASHINGTON. DC. 20006' 1202) 828·8S07 • FAX 12021452'0804 I INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR ELECTORAL SYSTEMS I The International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) is a private, nonprofit foundation that was established in September 1987 with a mandate to monitor, support and I strengthen the mechanics of the election process in emerging democracies and to undertake any I appropriate education activities which contribute toward free and fair elections. The Foundation fulfills its objectives through four major capabilities: election problem I analysis, technical election assistance, information transfer, and election observation. IFES' program activities have expanded dramatically since the worldwide shift toward I democratic pluralism and the ever-increasing demand for the technical support services of the I Foundation. -

Srno Name BOID No Allotedkitta 1 KRISHNA BAHADUR THAPA

srno name BOID_no AllotedKitta 1 KRISHNA BAHADUR THAPA 1301010000000436 10 2 BHUWAN POKHAREL 1301010000000761 10 3 LAXMI PRASAD KHAKUREL 1301010000001313 10 4 RAMESHWOR PRADHAN 1301010000001497 10 5 PRAKASH SHRESTHA 1301010000002530 10 6 BARSHANA SHAKYA 1301010000002695 10 7 SHREE RAM KHANAL 1301010000003023 10 8 PADMA MANANDHAR 1301010000004390 10 9 SHREE KRISHNA THAPA 1301010000004430 10 10 SAFAL SHRESTHA 1301010000004766 10 11 MANOJ KUMAR KHANAL 1301010000005852 10 12 TANKA BAHADUR SHRESTHA 1301010000006860 10 13 RAMBHA DEVI SHRESTHA 1301010000007218 10 14 ISHWOR KARKI 1301010000007505 10 15 TIL BAHADUR KHADKA CHHETRI 1301010000008190 10 16 SHUBHAM DHUNGANA 1301010000008319 10 17 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 1301010000009308 10 18 HEM BAHADUR LIMBU 1301010000009443 10 19 SWECHCHHA DAHAL 1301010000009561 10 20 SHYAM KRISHNA DAHAL 1301010000009589 10 21 SARASWATI ADHIKARI 1301010000009857 10 22 RAJENDRA KUMAR RAUT 1301010000009920 10 23 PRAKASH SINGH KATHAYAT 1301010000009954 10 24 SUBAS POUDEL 1301010000019293 10 25 DURLAV NEPAL 1301010000019713 10 26 PURNA PRASAD BHETUWAL 1301010000020581 10 27 PUSHPA KATUWAL 1301010000021281 10 28 GOMA SHRESTHA 1301010000021361 10 29 PRAKASH ARYAL 1301010000010345 10 30 BUDDHA KRISHNA MANANDHAR 1301010000010419 10 31 UMA MANANDHAR 1301010000010423 10 32 PURNA BAHADUR SANGAT 1301010000011013 10 33 SHIVA SHRESTHA 1301010000013920 10 34 RAM MANI KHANAL 1301010000014242 10 35 HIRA THAPA MAGAR 1301010000014911 10 36 PRABINA BHANDARI 1301010000015191 10 37 SHOBHITA KALIKA 1301010000015311 10 38 SHAWANTI SHARMA 1301010000016176 -

Prime Ministers of Nepal

Prime Ministers of Nepal Kingdom of Nepal (19th century-1990 ) • Damodar Pande • Rana Bahadur Shah Deva • Bhimsen Thapa • Rana Jang Pande • Ranga Nath Poudyal • Puskar Shah • Rana Jang Pande • Ranga Nath Poudyal • Fateh Jang Chautaria • Mathabarsingh Thapa • Fateh Jang Chautaria • Jang Bahadur • Bam Bahadur Kunwar Rana • Krishna Bahadur Kunwar Rana • Jang Bahadur • Renaudip Singh Bahadur • Bir Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana • Dev Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana • Chandra Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana • Bhim Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana • Juddha Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana • Padma Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana • Mohan Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana • Matrika Prasad Koirala • • vacant (1952–1953) • • Matrika Prasad Koirala • • vacant (1955–1956) • • Tanka Prasad Acharya • Kunwar Inderjit Singh • Subarna Shamsher Rana • Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala • Tulsi Giri • Surya Bahadur Thapa • Tulsi Giri • Surya Bahadur Thapa • Kirti Nidhi Bista • • vacant (1970–1971) • Kirti Nidhi Bista • Nagendra Prasad Rijal • Tulsi Giri • Kirti Nidhi Bista • Surya Bahadur Thapa • Lokendra Bahadur Chand • Nagendra Prasad Rijal • Marich Man Singh Shrestha • Lokendra Bahadur Chand Kingdom of Nepal (1990-2008 ) • Krishna Prasad Bhattarai • Girija Prasad Koirala • Man Mohan Adhikari • Sher Bahadur Deuba • Lokendra Bahadur Chand • Surya Bahadur Thapa • Girija Prasad Koirala • Krishna Prasad Bhattarai • Sher Bahadur Deuba • • vacant (2002) • • Lokendra Bahadur Chand • Surya Bahadur Thapa • Sher Bahadur Deuba • • vacant (2005–2006) • • Girija Prasad Koirala Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal (2008-present) • Girija Prasad Koirala • Prachanda • Madhav Kumar Nepal • Jhala Nath Khanal • Baburam Bhattarai • Khil Raj Regmi . -

Timeline of Constitutional Development in Nepal

Timeline of Constitutional Development in Nepal Pre-Constitutional Period [1768 – 1854] 1768: State of Nepal formed. Royal edicts and key Hindu scriptures formed the law of the land . Key advice sought from the traditional Consultative Court, the Bhardari Shava (Assembly of Lords) on issuing Royal edicts. 1846: Massacre of almost all members of Bhardari Shava by the Rana brothers led by Jung Bahadur. The infamous event known as the Kot Parba (Court Massacre) wiped out an entire generation of Nepal’s traditional courtiers, making the Rana family with the command of Army, most powerful in Nepal. Shah family looses its grip on power. 1856: The Shah King Surendra forced to grant a Panja Patra (Royal Seal) to vest henceforth sovereign power on the ruling Rana Prime Minsiters, to be exercised on behalf of reigning Shah Kings. The Panja Patra traditionally formed the ultimate instrument of delegating sovereign power claimed on tradition and divinity by the Shah dynasty. 1851: Re-establishment of Bhardari Shava, mostly composed of Rana family members and some civil servants, and essentially to act as rubber stamp of decrees issued by the ruling Rana Prime Minister, which essentially formed the law of the land. 1854: Proclaimation of Muluki Ain (Law of the Land), the first codification of traditional laws in common practice commissioned by Rana, Jung Bahadur. Three Early Constitutions [1947- 1959] 1947: Rana Prime Minister Padma Shamsher forms Constitution Reform Committee to draft first constitution of Nepal . Indian Constitutional experts invited. 1948: Government of Nepal Constitution Act, 1948 proclaimed by Padma Shamsher, which laid out the framework of a parliamentary system with a bicameral legislative body.