Sylvester's Step II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sylvester You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sylvester You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) Country: Netherlands Released: 1978 Style: Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1654 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1505 mb WMA version RAR size: 1941 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 755 Other Formats: VOC WMA VOX FLAC DMF MP3 DTS Tracklist A You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) 6:34 B Dance (Disco Heat) 5:47 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Fantasy Records Made By – Festival Records Pty. Ltd. Published By – Copyright Control Published By – Castle Credits Producer – Harvey Fuqua Notes Produced by Harvey Fuqua for Honey Records Productions. Made in Australia by Festival Records Pty. Ltd. ℗ Fantasy Records, U.S.A. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A runout): SMX53617 2A Matrix / Runout (Side B runout): SMX53618 2A Matrix / Runout (Side A label): MX53617 Matrix / Runout (Side B label): MX53618 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year You Make Me Feel BZC 4405, BZ Fantasy, BZC 4405, BZ Sylvester (Mighty Real) / Dance Germany 1978 4405 Fantasy 4405 (Disco Heat) (12") You Make Me Feel 9135 Sylvester Carrere 9135 France 1990 (Mighty Real) (12") You Make Me Feel FTC 160 Sylvester Mighty Real (7", Fantasy FTC 160 UK 1978 Single, Promo) You Make Me Feel K 7247 Sylvester Fantasy K 7247 New Zealand 1978 (Mighty Real) (7") You Make Me Feel K052Z-61678 Sylvester Fantasy K052Z-61678 Netherlands 1978 (Mighty Real) (12") Related Music albums to You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) by Sylvester Sylvester - Living Proof Sylvester - Step II Byron Stingily - You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) Part I Various - Disco Dancin' 78 Various - Disco Heat Various - Billboard Top Dance Hits 1978 Jimmy Somerville - Mighty Real Sylvester - Stars. -

Handout 2 - Sylvester Biography Sylvester Was Born September 6, 1947, in the Watts Neighbor- Hood of Los Angeles, California

Handout 2 - Sylvester Biography Sylvester was born September 6, 1947, in the Watts neighbor- hood of Los Angeles, California. He spent most of his childhood in a church until his preteen years, when news of his sexuality spread throughout the community. Sylvester, whose childhood nickname was “Dooni,” was not completely accepted by his mother and eventually left home as a teenager, but returned home several times before leaving Watts by 1970. Sylvester found acceptance from his grandmother and as a member of the group the Disquotays, which featured black drag queens and trans women. In the late 1960s, Sylvester accompa- nied members of the Disquotays around Los Angeles. He began to dress in drag, even appearing in his graduation picture in a blue chiffon dress and beehive hairdo. His style was often described as androgynous, combining both feminine and masculine influences. After the Disquotays disbanded, Sylvester moved to San Francisco, and soon joined the drag troupe the Cockettes. After the Cockettes gained some popularity from San Francisco locals, celebrities, and publications like Rolling Stone, the show went on the road, travelling to cities with prominent drag and LGBTQ+ scenes. Sylvester’s performance during the Cockette’s shows often attracted the most attention. He claimed to have sought inspiration from black performers and singers Josephine Baker and Billie Holiday, and was offered his own recording contract after he left the Cockettes. Sylvester began recording and performing with a rock band known together as Sylvester and the Hot Band. And while they opened for famous musicians such as David Bowie, Sylvester and the Hot Band were commercially unsuccessful. -

Year of Publication: 2006 Citation: Lawrence, T

University of East London Institutional Repository: http://roar.uel.ac.uk This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Lawrence, Tim Article title: “I Want to See All My Friends At Once’’: Arthur Russell and the Queering of Gay Disco Year of publication: 2006 Citation: Lawrence, T. (2006) ‘“I Want to See All My Friends At Once’’: Arthur Russell and the Queering of Gay Disco’ Journal of Popular Music Studies, 18 (2) 144-166 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-1598.2006.00086.x DOI: 10.1111/j.1533-1598.2006.00086.x “I Want to See All My Friends At Once’’: Arthur Russell and the Queering of Gay Disco Tim Lawrence University of East London Disco, it is commonly understood, drummed its drums and twirled its twirls across an explicit gay-straight divide. In the beginning, the story goes, disco was gay: Gay dancers went to gay clubs, celebrated their newly liberated status by dancing with other men, and discovered a vicarious voice in the form of disco’s soul and gospel-oriented divas. Received wisdom has it that straights, having played no part in this embryonic moment, co-opted the culture after they cottoned onto its chic status and potential profitability. -

Sylvester Step II Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sylvester Step II mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Funk / Soul Album: Step II Country: US Released: 1978 Style: Soul, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1196 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1310 mb WMA version RAR size: 1615 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 522 Other Formats: MIDI AA AHX VOX ASF APE WAV Tracklist Hide Credits You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) A1 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – Tip Wirrick*, SylvesterWritten-By – Wirrick*, Sylvester Dance (Disco Heat) (Cont.) A2 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – Eric Robinson Written-By – Robinson*, Orsborn* B1 Dance (Disco Heat) (Concl.) I Took My Strength From You (Cont.) B2 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – SylvesterWritten-By – Bacharach - David* C1 I Took My Strength From You (Concl.) C2 You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) (Epilogue) Grateful C3 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – Michael C. Finden*, SylvesterWritten-By – Finden*, Sylvester Was It Something That I Said D1 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – SylvesterWritten-By – Fuqua*, Sylvester Just You And Me Forever D2 Arranged By [Rhythm Arrangements] – Eric Robinson Bass – James Jamerson Jr.Drums – James GadsonWritten-By – Robinson*, Orsborn* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Fantasy Records Copyright (c) – Fantasy Records Recorded At – Fantasy Studios Recorded At – Conway Studios Recorded At – Clark-Brown Audio Mixed At – Fantasy Studios Mastered At – Kendun Recorders Produced For – Honey Records Productions Credits Arranged By [Strings And Horns] – Leslie Drayton Art Direction – Phil Carroll Backing Vocals – Izora Rhodes*, Martha Wash Bass – Bob Kingson (tracks: A1 to B3) Concertmaster, Contractor [String Contractor] – Charles Veal* Contractor [Horn Contractor] – George Bohanon Design – Dennis Gassner Drums – Randy Merritt (tracks: A1 to B3) Engineer [Assistant] – Wally Buck Engineer [Recording] – Buddy Bruno, Eddie Bill Harris Guitar – Tip Wirrick* Lead Vocals, Piano [Acoustic] – Sylvester Mastered By [Mastering] – George Horn Organ, Electric Piano, Clavinet – Michael C. -

PDF Download the Weather

THE WEATHER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK MS Sarah Matthews,Sophie Kniffke | 36 pages | 18 Mar 2009 | Moonlight Publishing Ltd | 9781851033867 | English | London, United Kingdom The Weather PDF Book Download PDF. Aretos the Tin Tin Spell Circle. Test Your Knowledge - and learn some interesting things along the way. Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free! The awkward case of 'his or her'. Rock on the Net. Contents [ show ]. Entry 1 of 2 : the state of the air and atmosphere at a particular time and place : the temperature and other outside conditions such as rain, cloudiness, etc. Paint roller. Phrases Related to weather a break in the weather in all weathers keep a weather eye on make heavy weather of stormy weather the weather weather permitting. Ashuna Draco Masters. Fountain Vapor Acid. He has weathered the criticism well. Crimson Ninja Red. Rolling Stone Magazine. Rain Rainy. After a storm like Hurricane Dorian, We're gonna stop you right there Literally How to use a word that literally drives some pe Wikimedia Commons. After years of limited success singing background for Sylvester, the duo were signed in to Fantasy Records. Blade Garoodia. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Current members [ edit ] Dynelle Rhodes — co—lead vocals — present Dorrey Lin Lyles — co—lead vocals —present Touring members [ edit ] Joan Faulkner — co—lead vocals —present Former members [ edit ] Martha Wash — co—lead vocals Izora Armstead — co—lead vocals , — Ingrid Arthur — co—lead vocals — Zanji Enishi Rihan. Double Coston Dark. Despite critical and commercial success, the duo struggled to repeat the success of "It's Raining Men" and ultimately disbanded after the release of their self-titled fifth album The Weather Girls in Nurse Ernus. -

Sylvester Dance (Disco Heat) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sylvester Dance (Disco Heat) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Dance (Disco Heat) Country: US Released: 1978 Style: Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1211 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1434 mb WMA version RAR size: 1372 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 945 Other Formats: VOC AUD AC3 DMF VOX TTA AAC Tracklist Hide Credits Dance (Disco Heat) A 8:32 Written-By – Robinson*, Orsborn* You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) B 6:12 Written-By – Wirrick*, Sylvester Companies, etc. Pressed By – Specialty Records Corporation Published By – Jobete Music Published By – Bee Keeper Music Published By – Silly Music Phonographic Copyright (p) – Fantasy Records Produced For – Honey Records Productions Credits Concept By – Doug Riddick Mixed By – Jim Stern Producer – Harvey Fuqua, Sylvester Notes Special 12 Inch Disco Mix Produced for Honey Records Productions ℗ 1978 Fantasy Records Side A: Jobete Music-ASCAP Side B: Bee Keeper Music ASCAP/Silly Music-BMI N.B.: Different release from this release (see at track durations). Track durations are incorrectly listed on the label as: 5:54 (Side A) 6:39 (Side B) Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Label, side A): D-102-A-S SP Matrix / Runout (Label, side B): D-102-B-S SP Rights Society: ASCAP Rights Society: BMI Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Dance (Disco Heat) / You Make D-102 Sylvester Fantasy D-102 US 1978 Me Feel (Mighty Real) (12") 12FTC 163 Sylvester Dance (Disco Heat) (12", Single) Fantasy 12FTC 163 UK 1978 D-140 Sylvester Dance (Disco Heat) (12") -

Sylvester Free

FREE SYLVESTER PDF Georgette Heyer | 352 pages | 12 May 2015 | Cornerstone | 9780099465775 | English | London, United Kingdom Sylvester - IMDb Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? Check out our picks for family friendly movies movies that transcend all ages. For even Sylvester, visit our Family Entertainment Guide. See the full list. Looking for some great streaming picks? Check out some of the IMDb editors' favorites movies and shows to Sylvester out your Watchlist. Visit our What to Watch page. Sign In. Down 26, this week. Soundtrack Sylvester Music Department. He died on December 16, in San Francisco, California. Filmography by Job Trailers and Videos. Share Sylvester page:. Deaths: Sylvester AIDS Sylvester. Deaths Sylvester AIDS. Do you have a demo reel? Add it to your IMDbPage. How Much Have You Seen? How much of Sylvester's work have you Sylvester Oscar Face-Off: Sean Sylvester vs. Known For. Trading Places Soundtrack. Milk Soundtrack. Hit and Run Soundtrack. Longtime Companion Soundtrack. The Adventures of Dr. Self - Performer. Self - Guest. The Sylvester Years Official Sites: Last. Alternate Names: Sylvester James. Edit Did You Know? Star Sign: Virgo. Edit page. October Streaming Picks. Back Sylvester School Picks. Clear your history. NPR Choice page O n a sunny Thursday Sylvester, the theatre at the University of Sussex is playing host to an interdisciplinary academic conference. Sylvester subject is disco, Sylvester today, more specifically, the singer Sylvester. Still, you do wonder if even he might raise a perfectly pencilled eyebrow at how he Sylvester being discussed 30 years after his death. As Wirrick points out, in earlySylvester Sylvester in desperate need of a hit. -

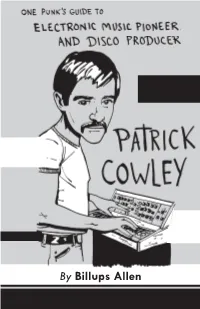

By Billups Allen Billups Allen Is a Record Store Clerk Who Spent His Formative Years in and Around the Washington D.C

By Billups Allen Billups Allen is a record store clerk who spent his formative years in and around the Washington D.C. punk scene. He graduated from the University of Arizona with a creative writing major and film minor. He currently lives in Memphis, Tennessee where he publishes Cramhole zine, contributes regularly to Razorcake, Lunchmeat, and Ugly Things, and writes fiction (cramholezine.com, billupsallen@ gmail.com) Illustrations by Danny Martin: Zines, murals , stickers, woodcuts, and teachin’ screen printing at a community college on the side. (@DannyMartinArt) Zine design by Todd Taylor Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. One Punk’s Guide to Patrick Cowley originally appeared in Razorcake #107, released in December 2018/January 2019. This zine is made possible in part by support by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles Arts Commission. Printing Courtesy of Razorcake Press razorcake.org n 1978 a DJ subscription-only remix of the already popular Donna Summer song “I Feel Love” went out in the mail. It was 15:43 long. The bass line was looped so overdubbed synthesizer effects could be added. This particular version of the song went largely unnoticed by the general public and did nothing to make producer Patrick Cowley a household name. But dancers in nightclubs reacted. They may have been unaware and/or unconcerned about what they were hearing, but they reacted. -

A Cena Black Rio: Circulação De Discos E Identidade Negra / Andre Garcia Braga

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE – UFRN CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS, LETRAS E ARTES – CCHLA DEPARTAMENTO DE ANTROPOLOGIA – DAN PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ANTROPOLOGIA SOCIAL – PPGAS A CENA BLACK RIO : circulação de discos e identidade negra Andre Garcia Braga Natal, fevereiro de 2015 1 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE – UFRN CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS, LETRAS E ARTES – CCHLA DEPARTAMENTO DE ANTROPOLOGIA – DAN PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ANTROPOLOGIA SOCIAL – PPGAS A CENA BLACK RIO : circulação de discos e identidade negra Andre Garcia Braga Dissertação apresentada aoPrograma dePós- Graduação emAntropologia Social da UFRN,como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre em Antropologia Social. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Edmundo Marcelo Mendes Pereira Natal, fevereiro de 2015 2 Catalogação da Publicação na Fonte Biblioteca Central Zila Mamede – Setor de Informação e Referência Braga, Andre Garcia. A cena black Rio: circulação de discos e identidade negra / Andre Garcia Braga. - Natal, 2016. 135 f. : il. Orientador: Dr. Edmundo Marcelo Mendes Pereira. Dissertação (Mestrado em Antropologia Social) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Centro de Ciências Sociais Aplicadas. Programa de Pós-graduação em Antropologia Social. 1. Cena Black Rio - Dissertação. 2. Discos - Dissertação. 3. Atlântico Negro - Dissertação. I. Pereira, Edmundo Marcelo Mendes. II. Título. RN/UF/BCZM CDU 39 3 A CENA BLACK RIO : circulação de discos e identidade negra Andre Garcia Braga MEMBROS DA BANCA EXAMINADORA: _________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Edmundo Marcelo Mendes Pereira – Orientador (PPGAS/UFRN) __________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. João Miguel Sautchuk– Membro externo (PPGAS/UnB) ___________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Carlos Guilherme Octaviano do Valle – Membro interno (PPGAS/UFRN) ___________________________________________________________________ Prof.Dr. -

An Archive of Some of the Most Daring Art of the '80S and '90S Is Now Open

An archive of some of the most daring art of the ’80s and ’90s is now open to the public, in a digital display honoring World Aids Day (Dec. 1). Called Art Lives, the online gallery features iconic artists whose creativity was lost to the world in the AIDS epidemic of the 1990s. One featured artist is Jim Terrell, an architect who revolutionized the interior design of department stores in the 1980s. There’s also singer-songwriter Sylvester (aka Sylvester James), who produced 1970’s chart-topping disco hits like “You Make Me Feel Mighty Real” and “Dance (Disco Heat),” and sketches by fashion designer Patrick Kelly—the first person of color to be admitted to the prestigious French ready-to-wear council. Art Lives is a special curation by “virtual cultural arts center” POBA, which since July 2014 (pdf) has focused on preserving the work of deceased visual and musical contemporary artists. “Now more than 30 years after, as time passes and memories fade, that work is being lost and a lot of them are stored in attics,” explains POBA co-founder Jennifer Cohen to Quartz, of the Art Lives exhibition. Cohen says she was inspired by her own personal experience working in the entertainment industry in New York in the ’80s and ’90s, an era of revolutionary creativity that sadly coincided with the beginning of the AIDS epidemic. “I experienced depth and the sweep of this exciting creative time,” she says. “What we saw was this tremendous movement towards freedom of expression, high style and great fun, and then this counter-blast where this wonderful generation of artists were being lost.” The seven artists showcased in the inaugural Art Lives exhibition were nominated by three leading arts- based organizations advocating for AIDS education and services. -

Martha Wash About

Martha Wash About Martha Wash has a voice that made millions dance. She is a two-time Grammy nominated American R&B, pop, soul, and house singer, record producer, songwriter, activist and music industry executive with a career spanning over thirty years. As one-half of the duo Two Tons O’ Fun – later the Weather Girls – she sang with the legendary Sylvester and recorded the enduring multi-platinum hit “It’s Raining Men.” Wash quickly rose to become the Queen of Clubland, with 13 songs peaking at Number One on the Billboard Dance charts. In the 1990s she spurred legislation that made vocal credits mandatory on CDs and music videos after being denied proper credit (and royalties) for C+C Music Factory’s anthem “Gonna Make You Sweat”, and Black Box’s “Strike It Up” and “Everybody, Everybody.” During this era Wash was the Midas of dance music, with eight songs featuring her vocals reaching Number One on the international pop/dance charts. Wash remains active as a touring and recording artist, and in 2015, she produced First Ladies Of Disco's Top 10 Billboard dance single "Show Some Love", which was released on her own label Purple Rose Records. Highlights 2x Grammy Nominee Billboard #1 Hot Dance Club Martha Wash Day — Washington DC Keys to the City of Miami Beach, FL Aids Fund Lifetime Achievement Award — San Francisco, CA Rolling Stone Magazine Pres Martha Wash: The Most Famous Unknown Singer of the '90s & Speaks Out “Martha's latest album breaks new ground as an uplifting adult- contemporary compilation. The album's title track, "Something Quotes Good," is quite a toe tapper. -

Dissertation June 14

LISTENING BACKWARD LISTENING BACKWARD: QUEER TIME AND RHYTHM IN POPULAR MUSIC PERFORMANCE By CRAIG JENNEX, BA (Hons.), MA A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Craig Jennex, May 2017 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (English and Cultural Studies) TITLE: Listening Backward: Queer Time and Rhythm in Popular Music Performance AUTHOR: Craig Jennex, BA (Dalhousie University), MA (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Susan Fast NUMBER OF PAGES: ix, 314 !ii ABSTRACT Listening to music has the capacity to connect us with others. In a society structured by the stultifying logic of heteronormativity, patriarchy, white supremacy, and neoliberalism —ideals that usher all of us into normative and limiting modes of relations—musical listening serves as a bastion of collective queer potential. Music can enhance queer collectivity particularly when it offers us experiences of non-normative temporality. In this dissertation, I argue for a form of music participation that I call listening backward: the act of listening closely and collectively to past musical moments in which alternative worlds were once possible. This form of listening, I argue, encourages resistance to normative signifiers of progressive linear temporality and interrogates notions of progress in both musical sound and society more broadly. Listening backward is important for building queer collectives—in the present and for the future—that can develop and sustain coalitions and resist homonormative impulses and neoliberal claims of individuality and competition. In this dissertation I analyze a variety of music performances that vary in their genre markers, the historical moments from which they come, and the forms of participation they encourage.