Association of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Different Influences of Endometriosis and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease On

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Different Influences of Endometriosis and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease on the Occurrence of Ovarian Cancer Jing-Yang Huang 1,2,†, Shun-Fa Yang 1,2 , Pei-Ju Wu 1,3,†, Chun-Hao Wang 4,†, Chih-Hsin Tang 5,6,7 and Po-Hui Wang 1,2,3,8,* 1 Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung 402, Taiwan; [email protected] (J.-Y.H.); [email protected] (S.-F.Y.); [email protected] (P.-J.W.) 2 Department of Medical Research, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung 402, Taiwan 3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung 402, Taiwan 4 Department of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei 106, Taiwan; [email protected] 5 School of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung 404, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Chinese Medicine Research Center, China Medical University, Taichung 404, Taiwan 7 Department of Medical Laboratory Science and Biotechnology, College of Medical and Health Science, Asia University, Taichung 413, Taiwan 8 School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung 402, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] † Equal contributions as first authors. Abstract: To compare the rate and risk of ovarian cancer in patients with endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). A nationwide population cohort research compared the risk of ovarian cancer in 135,236 age-matched comparison females, 114,726 PID patients, and 20,510 endometriosis patients out of 982,495 females between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2014 and ended on the date Citation: Huang, J.-Y.; Yang, S.-F.; of confirmation of ovarian cancer, death, or 31 December 2014. -

Understanding Endometriosis - Information Pack

Understanding Endometriosis - Information Pack What is endometriosis? Endometriosis (pronounced en- doh – mee – tree – oh – sis) is the name given to the condition where cells like the ones in the lining of the womb (uterus) are found elsewhere in the body. Every month a woman’s body goes through hormonal changes. Hormones are naturally released which cause the lining of the womb to increase in preparation for a fertilized egg. If pregnancy does not occur, this lining will break down and bleed – this is then released from the body as a period. Endometriosis cells react in the same way – except that they are located outside the womb. During the monthly cycle hormones stimulate the endometriosis, causing it to grow, then break down and bleed. This internal bleeding, unlike a period, has no way of leaving the body. This leads to inflammation, pain, and the formation of scar tissue (adhesions). Endometriosis is not an infection. Endometrial tissue can also be found in the ovary, Endometriosis is not contagious. where it can form cysts, called ‘chocolate cysts’ Endometriosis is not cancer. because of their appearance. Endometriosis is most commonly found inside the pelvis, around the ovaries, the fallopian tubes, on the outside of the womb or the ligaments (which hold the womb in place), or the area between your rectum and your womb, called the Pouch of Douglas. It can also be found on the bowel, the bladder, the intestines, the vagina and the rectum. You can also have endometrial tissue that grows in the muscle layer of the wall of the womb (this is another condition called adenomyosis). -

Differential Diagnosis of Endometriosis by Ultrasound

diagnostics Review Differential Diagnosis of Endometriosis by Ultrasound: A Rising Challenge Marco Scioscia 1 , Bruna A. Virgilio 1, Antonio Simone Laganà 2,* , Tommaso Bernardini 1, Nicola Fattizzi 1, Manuela Neri 3,4 and Stefano Guerriero 3,4 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Policlinico Hospital, 35031 Abano Terme, PD, Italy; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (B.A.V.); [email protected] (T.B.); [email protected] (N.F.) 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, “Filippo Del Ponte” Hospital, University of Insubria, 21100 Varese, VA, Italy 3 Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Cagliari, 09124 Cagliari, CA, Italy; [email protected] (M.N.); [email protected] (S.G.) 4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria, Policlinico Universitario Duilio Casula, 09045 Monserrato, CA, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 October 2020; Accepted: 15 October 2020; Published: 20 October 2020 Abstract: Ultrasound is an effective tool to detect and characterize endometriosis lesions. Variances in endometriosis lesions’ appearance and distorted anatomy secondary to adhesions and fibrosis present as major difficulties during the complete sonographic evaluation of pelvic endometriosis. Currently, differential diagnosis of endometriosis to distinguish it from other diseases represents the hardest challenge and affects subsequent treatment. Several gynecological and non-gynecological conditions can mimic deep-infiltrating endometriosis. For example, abdominopelvic endometriosis may present as atypical lesions by ultrasound. Here, we present an overview of benign and malignant diseases that may resemble endometriosis of the internal genitalia, bowels, bladder, ureter, peritoneum, retroperitoneum, as well as less common locations. An accurate diagnosis of endometriosis has significant clinical impact and is important for appropriate treatment. -

Women's Health

Women’s Health Kristen Jones, DO Osteopathic Faculty St. Luke’s Family Medicine Residency Bethlehem, PA ACOFP exam • Women’s Issues (4% of test – OB/GYN = 4%) between 4-6% • Common Topics • Vaginal Discharge • Pelvic Pain • Cancer risk factors • Menstrual disorders • Breast Discharge • Eang disorders • Osteoporosis • HRT • 23 yo with vaginal discharge. Sexually ac[ve. Pelvic exam reveals: • Thin gray-white discharge, pH 5, a strong fishy odor is present when KoH is added to the discharge. • A)Bacterial Vaginosis • B)Gonorrhea • C)Chlamydia • D)Candida • E)Physiologic Discharge • 23 yo with vaginal discharge. Sexually ac[ve. Pelvic exam reveals: • Thin gray-white discharge, pH 5, a strong fishy odor is present when KoH is added to the discharge. • A)Bacterial Vaginosis • B)Gonorrhea • C)Chlamydia • D)Candida • E)Physiologic Discharge Bacterial Vaginosis • pH >4.5 • +Whiff Test • +Clue cells – epithelial cells with adherent bacteria. • Caused by Gardnerella • Treat with Flagyl 500mg po q12hx7 days (safe in pregnancy) • 23 yo with vaginal discharge. Sexually ac[ve. Pelvic exam reveals: • pH <4, vulvar erythema, thick white discharge • Most likely cause is: • A)Bacterial Vaginosis • B)Trichomonas • C)Chlamydia • D)Candida • E)Physiologic Discharge • 23 yo with vaginal discharge. Sexually ac[ve. Pelvic exam reveals: • pH <4.5, vulvar erythema, thick white discharge • Most likely cause is: • A)Bacterial Vaginosis • B)Trichomonas • C)Chlamydia • D)Candida • E)Physiologic Discharge Vaginal Candidiasis • pH <4.5 • Budding yeast and hyphae on KOH • Thick white, chunky discharge • Vulvar erythema and pruri[s • Treat with PO fluconazole 150mg po x1 • Treat with PV clotrimazole or miconazole for 7 days during pregnancy • 23 yo with vaginal discharge. -

Update on Treatment of Menstrual Disorders

THE REPRODUCTIVE YEARS Update on treatment of menstrual disorders Martha Hickey and Cynthia M Farquhar DISTURBANCES OF MENSTRUAL BLEEDING are a major social and medical problem for women, their families and ABSTRACT the health services, and a common reason for women to ■ There is evidence from well designed randomised controlled consult their general practitioners or gynaecologists. In the trials that modern medical and conservative surgical United Kingdom, each year one in 20 women consult their therapies (including endometrial ablation) are effective GPs aboutThe Medical heavy Journal menstrual of Australia bleeding. ISSN:1 0025-729X 16 June treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding for many women. Heavy2003 bleeding178 12 625-629 is the most common menstrual com- ■ Submucous fibroids may be resected directly via the plaint.©The In Medicalmost cases,Journal thisof Australia has no 2003 identifiable www.mja.com.au pelvic or The reproductive years hysteroscope, reducing menstrual bleeding, although data systemic cause and is termed dysfunctional uterine bleed- are available only from case series. ing. Irregular dysfunctional uterine bleeding is generally ■ associated with anovulation. Historically, many women with Endometriosis is common, may also occur in young women heavy menstrual bleeding were advised to undergo hysterec- and may present with atypical or non-cyclical symptoms; tomy, which was the only way of ensuring a “cure”. conservative laparoscopic surgery increases fecundity and However, a range of new and effective interventions can now reduces dysmenorrhoea and dyspareunia. be offered for dysfunctional uterine bleeding and other ■ Randomised trials of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system common causes of menstrual disorder, such as fibroids and in women with menorrhagia have shown that hysterectomy endometriosis. -

Vaginitis and Cervicitis in the Clinic 2009.Pdf

in the clinic Vaginitis and Cervicitis Prevention page ITC3-2 Screening page ITC3-3 Diagnosis page ITC3-5 Treatment page ITC3-10 Practice Improvement page ITC3-14 CME Questions page ITC3-16 Section Co-Editors: The content of In the Clinic is drawn from the clinical information and Christine Laine, MD, MPH education resources of the American College of Physicians (ACP), including Sankey Williams, MD PIER (Physicians’ Information and Education Resource) and MKSAP (Medical Knowledge and Self-Assessment Program). Annals of Internal Medicine Science Writer: editors develop In the Clinic from these primary sources in collaboration with Jennifer F. Wilson the ACP’s Medical Education and Publishing Division and with the assistance of science writers and physician writers. Editorial consultants from PIER and MKSAP provide expert review of the content. Readers who are interested in these primary resources for more detail can consult http://pier.acponline.org and other resources referenced in each issue of In the Clinic. CME Objective: To gain knowledge about the management of patients with vagini- tis and cervicitis. The information contained herein should never be used as a substitute for clinical judgment. © 2009 American College of Physicians in the clinic he vagina has a squamous epithelium and is susceptible to bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, and candidiasis. Vaginitis may also result Tfrom irritants, allergic reactions, or postmenopausal atrophy. The endocervix has a columnar epithelium and is susceptible to infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, or less commonly, herpes sim- plex virus. Vaginitis causes discomfort, but rarely has serious consequences except during pregnancy and gynecologic surgery. Cervicitis may be asymptomatic and if untreated, can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which can damage the reproductive organs and lead to infertility, ectopic pregnancy, or chronic pelvic pain. -

Intricate Connections Between the Microbiota and Endometriosis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Intricate Connections between the Microbiota and Endometriosis Irene Jiang, Paul J. Yong, Catherine Allaire and Mohamed A. Bedaiwy * Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of British Columbia, D415A-4500 Oak Street, Vancouver, BC V6H 3N1, Canada; [email protected] (I.J.); [email protected] (P.J.Y.); [email protected] (C.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +604-875-2000 (ext. 4310) Abstract: Imbalances in gut and reproductive tract microbiota composition, known as dysbiosis, disrupt normal immune function, leading to the elevation of proinflammatory cytokines, compro- mised immunosurveillance and altered immune cell profiles, all of which may contribute to the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Over time, this immune dysregulation can progress into a chronic state of inflammation, creating an environment conducive to increased adhesion and angiogenesis, which may drive the vicious cycle of endometriosis onset and progression. Recent studies have demonstrated both the ability of endometriosis to induce microbiota changes, and the ability of antibiotics to treat endometriosis. Endometriotic microbiotas have been consistently associated with diminished Lactobacillus dominance, as well as the elevated abundance of bacterial vaginosis-related bacteria and other opportunistic pathogens. Possible explanations for the implications of dysbiosis in endometriosis include the Bacterial Contamination Theory and immune activation, cytokine- impaired gut function, altered estrogen metabolism and signaling, and aberrant progenitor and stem-cell homeostasis. Although preliminary, antibiotic and probiotic treatments have demonstrated efficacy in treating endometriosis, and female reproductive tract (FRT) microbiota sampling has Citation: Jiang, I.; Yong, P.J.; Allaire, successfully predicted disease risk and stage. -

Endometriosis Fact Sheet

ABOUT ENDOMETRIOSIS • Endometriosis is a chronic and painful disease that affects an estimated one in 10 women of reproductive age.1 FAST • Women with endometriosis can suffer for up to six to 10 years and visit multiple physicians before receiving a proper diagnosis.2,3 • Symptoms related to endometriosis vary4 and some symptoms are associated with pain that can be debilitating4,5 FACTS 5 and may interfere with day-to-day activities. • There is no known cure6 for endometriosis, but treatment options are available.1 Endometriosis occurs when tissue similar to that normally found in the uterus begins to grow outside of the uterus where it doesn’t belong.1 These growths are called lesions and can occur on the ovaries, the fallopian tubes, or other areas near the uterus, such as the bowel or bladder.1 Endometriosis is an estrogen dependent disease, meaning estrogen fuels the growth of the lesions.3 SYMPTOMS Women with endometriosis may experience a range of symptoms that can be unpredictable and change over time; while others may experience no symptoms at all.7 There are many symptoms of endometriosis, but the most common symptoms are:7 • Painful periods • Pelvic pain in between periods • Pain with sex DIAGNOSIS The diagnosis experience may be prolonged because of the variety of pain symptoms.4 Women with endometriosis may go through one or more of these diagnostic steps:7 • Doctor’s appointment to discuss symptoms • Pelvic exam • Ultrasound • Blood test (to rule out other conditions) • Laparoscopy (surgery can help confirm the diagnosis of endometriosis) For US Media Only 35V-1939034 1 ABOUT ENDOMETRIOSIS (cont.) TREATMENT There is no known cure for endometriosis.6 It’s important for women to be specific about their symptoms when speaking to a healthcare provider. -

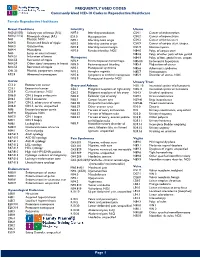

Commonly Used ICD-10 Codes in Reproductive Healthcare

FREQUENTLY USED CODES Commonly Used ICD-10 Codes in Reproductive Healthcare Female Reproductive Healthcare Breast Conditions Infertility Uterus N60.(01/02) Solitary cyst of breast (R/L) N97.0 Infertility-anovulation C54.1 Cancer of endometrium N60.(11/12) Fibrocystic change (R/L) E23.0 Hypopituarism C54.2 Cancer of myometrium N61 Mastitis, NOS N97.1 Infertility-tubal origin C54.3 Cancer of fundus uteri N64.0 Fissure and fistula of nipple N97.2 Infertility-uterine origin C54.9 Cancer of corpus uteri, unspec. N64.3 Galactorrhea N97.8 Infertility-cervical origin D25.9 Uterine myoma N64.4 Mastodynia N97.9 Female infertility, NOS N84.0 Polyp of corpus uteri N63 Lump or mass in breast N84.8 Polyp of other parts of fem genital N64.51 Induration of breast Menopause N84.9 Polyptract of fem. genital tract, unspec. N64.53 Retraction of nipple N92.4 Perimenopausal menorrhagia N85.00 Endometrial hyperplasia N64.59 Other signs/ symptoms in breast N95.0 Postmenopausal bleeding N85.4 Malposition of uterus N64.53 Retraction of nipple N95.1 Menopausal syndrome N85.6 Asherman’s syndrome O91.23 Mastitis, postpartum, unspec. N95.2 Atrophic vaginitis N85.7 Hematometra R92.8 Abnormal mammogram N95.8 Symptoms w artificial menopause N85.9 Disorder of uterus, NOS N95.9 Menopausal disorder NOS Cervix Urinary Tract C53.0 Endocervical cancer Ovary and Adnexa N30. 10 Interstitial cystitis w/o hematuria C53.1 Exocervical cancer C56.1 Malignant neoplasm of right ovary N30.11 Interstitial cystitis w/ hematuria C53.9 Cervical cancer, NOS C56.2 Malignant neoplasm of left -

SURGICAL TUTORIAL 1: Before, During and After- Comprehensive Team Approach to Laparoscopic Management of Severe Endometriosis

SYLLABUS SURGICAL TUTORIAL 1: Before, During and After- Comprehensive Team Approach to Laparoscopic Management of Severe Endometriosis Be a Surgical “Multiplier” in MIGS Inspire Brilliance Through Teamwork Scientific Program Chair Honorary Chair President Jubilee Brown, MD Barbara S. Levy, MD Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, MD Professional Education Information Target Audience This educational activity is developed to meet the needs of surgical gynecologists in practice and in training, as well as other healthcare professionals in the field of gynecology. Accreditation AAGL is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians. The AAGL designates this live activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Disclosure of Relevant Financial Relationships As a provider accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, AAGL must ensure balance, independence, and objectivity in all CME activities to promote improvements in health care and not proprietary interests of a commercial interest. The provider controls all decisions related to identification of CME needs, determination of educational objectives, selection and presentation of content, selection of all persons and organizations that will be in a position to control the content, selection of educational methods, and evaluation of the activity. Course chairs, planning committee members, presenters, authors, moderators, panel members, and others in a position to control the content of this activity are required to disclose relevant financial relationships with commercial interests related to the subject matter of this educational activity. -

Advice for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB) Services and Commissioners November 2014 Advice for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB) Services and Commissioners Contents

Advice for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB) Services and Commissioners November 2014 Advice for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB) Services and Commissioners Contents 1. Background 2 2. The National HMB Audit 4 3. Implications for service delivery 5 4. Implications for commissioners 7 References 10 1 Advice for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB) Services and Commissioners 1. Background Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is a prevalent condition that affects 20–30% of women of a reproductive age1. It can occur alone or in combination with other symptoms such as dysmenorrhoea (painful periods) and is frequently associated with endometriosis and adenomyosis or uterine fibroids. Several treatment options can be administered in primary care with varying levels of effectiveness. In England and Wales, about 80 000 women a year with HMB are referred for the first time to secondary care and approximately 30 000 undergo surgical treatment1, 2. Over the past 20 years, there have been new developments in the management of women with HMB, namely the levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system (IUS) (a cost-effective first-line treatment especially when fertility preservation is desirable), endometrial ablation (as an alternative to the definitive treatment hysterectomy) and uterine artery embolisation (UAE) (as an alternative to myomectomy and hysterectomy for uterine fibroids). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued a clinical guideline (2007)3 and quality standard (2013)4 for the management of women with HMB (Figure 1). The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) included guidance on the management of women with HMB in their standards for gynaecology (2008)5. The RCOG, on behalf of HQIP, also conducted a four-year national audit from 2010 to 2013 to examine the care received by women with HMB and to assess patient outcomes and experience of care1, 2, 6, 7. -

Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis of Dyspareunia LORI J

PROBLEM-ORIENTED DIAGNOSIS Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis of Dyspareunia LORI J. HEIM, LTC, USAF, MC, Eglin Air Force Base, Florida Dyspareunia is genital pain associated with sexual intercourse. Although this con- dition has historically been defined by psychologic theories, the current treatment O A patient infor- approach favors an integrated pain model. Identification of the initiating and pro- mation handout on dyspareunia, written mulgating factors is essential to reaching a successful diagnosis. The differential by the author of this diagnoses include vaginismus, inadequate lubrication, atrophy and vulvodynia article, is provided (vulvar vestibulitis). Less common etiologies are endometriosis, pelvic congestion, on page 1551. adhesions or infections, and adnexal pathology. Urethral disorders, cystitis and interstitial cystitis may also cause painful intercourse. The location of the pain may be described as entry or deep. Vulvodynia, atrophy, inadequate lubrication and vaginismus are associated with painful entry. Deep pain occurs with the other con- ditions previously noted. The physical examination may reproduce the pain, such as localized pain with vulvar vestibulitis, when the vagina is touched with a cotton swab. The involuntary spasm of vaginismus may be noted with insertion of an examining finger or speculum. Palpation of the lateral vaginal walls, uterus, adnexa and urethral structures helps identify the cause. An understanding of the present organic etiology must be integrated with an appreciation of the ongoing psycho- logic factors and negative expectations and attitudes that perpetuate the pain cycle. (Am Fam Physician 2001:63:1535-44,1551-2.) Members of various yspareunia is genital pain ex- Epidemiology family practice depart- perienced just before, during ments develop articles There are few reports of clinical trials relat- 1 for “Problem-Oriented or after sexual intercourse.