UNIT 3 EVOLUTION and INVOLUTION Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 38, No. 1 (Spring 2013)

Spring 2013 Journal of the Integral Yoga of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother Vol. 38, No. 1 Zackaria Moursi: Preparing for the winter journey • Ritam: The New World • Beloo Mehra: Search for a group-soul: The case of Indian-Americans • Ruth Lamb: Individuation: Activating the four powers • Richard Pearson: On the passing away of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother • Pravir Malik: Personal transformation and power • Current affairs • AV almanac • Source material • Poetry • AproposSpring 2013 Collaboration • 1 About the cover Title: Psychic joy in the U.N. This is a greyscale reproduction of a color painting (pencils with Table of contents Collaboration, vol. 38, no. 1, Spring 2013 watercolor) by Mirajyoti ([email protected]. in) who has lived in Auroville since 1989 and formerly lived in the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. It is part of a collection in soft pastels which has been set to music on a DVD which is avail- From the office ofCollaboration able from the artist ([email protected]). Mirajyoti is also an editor and she coedited the Notes on this issue ............................................................Larry Seidlitz 3 popular book The Hierarchy of Minds with Prem Sobel, among other works. Current affairs The authors and poets New study guides and e-books .................................. Santosh Krinsky 4 Mandakini Gupta is a newcomer Aurovilian Matagiri news ...................................................................... Julian Lines 4 who is on the editoral staff of Auroville Today. She Savitri Immersion at Lodi .................................................Lucie Seidlitz 4 may be reached at: [email protected]. Kailas Jhaveri is a long-time resident of the Sri FWE reaches milestone ................................................... Jerry Schwartz 4 Aurobindo Ashram. She has written an account of her life in two volumes of “I am with you.” Ruth Lamb, R.N., Ph.D. -

Nirodbaran Talks with Sri Aurobindo 01

Talks with Sri Aurobindo Volume 1 by Nirodbaran Sri Aurobindo Ashram Pondicherry NOTE These talks are from my notebooks. For several years I used to record most of the conversations which Sri Aurobindo had with us, his attendants, and a few others, after the accident to his right leg in November 1938. Besides myself, the regular participants were: Purani, Champaklal, Satyendra, Mulshankar and Dr. Becharlal. Occasional visitors were Dr. Manilal, Dr. Rao and Dr. Savoor. As these notes were not seen by Sri Aurobindo himself, the responsibil- ity for the Master's words rests entirely with me. I do not vouch for absolute accuracy, but I have tried my best to reproduce them faithfully. I have made the same attempt for the remarks of the others. NIRODBARAN i PREFACE The eve of the November Darshan, 1938. The Ashram humming with the ar- rival of visitors. On every face signs of joy, in every look calm expectation and happiness. Everybody has retired early, lights have gone out: great occa- sion demands greater silent preparation. The Ashram is bathed in an atmos- phere of serene repose. Only one light keeps on burning in the corner room like a midnight vigil. Sri Aurobindo at work as usual. A sudden noise! A rush and hurry of feet breaking the calm sleep. 2:00 a.m. Then an urgent call to Sri Aurobindo's room. There, lying on the floor with his right knee flexed, is he, clad in white dhoti, upper body bare, the Golden Purusha. The Mother, dressed in a sari, is sitting beside him. -

Preparing Miraculous

Eleven talks at Auroville Preparing for the Miraculous Georges Van Vrekhem Eleven Talks at Auroville Preparing for the Miraculous Georges Van Vrekhem Stichting Aurofonds © Georges Van Vrekhem All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or translated into any language in India or abroad in any form or by any means without permission of the author. ISBN : 81-87582-09-X First edition : May 2011 Printed in India Cover design, layout and printing by Brihat Consultants (India) Pvt. Ltd. [email protected] Table of Contents Foreword 1 Adam Kadmon and the Evolution 1 2 The Development of Sri Aurobindo’s Thought 25 3 Preparing for the Miraculous 43 4 What Arjuna Saw: the Dark Side of the Force 71 5 2010 and 1956: Doomsday? 93 6 Being Human and the Copernican Principle 117 7 Bridges across the Afterlife 147 8 Sri Aurobindo’s Descent into Death 171 9 Sri Aurobindo and the Big Bang 191 10 Theodicy: “Nature Makes No Mistakes” 213 11 The Kalki Avatar 235 Biographical Note 267 Foreword The talks in this book have been delivered in Auroville, the first four at the Townhall in September, the following six at Savitri Bhavan in November and December 2010. The talk on “The Kalki Avatar” was also held at the Townhall, in February 2011, in the context of the seminar on “Muta- tion II”. I had been invited to give talks in Europe, the USA and India, but I had to cancel all travelling plans because of my heart condition. This led to the idea of giving a series of talks in Auroville, where I am living, and to record them so that the people who had invited me would be able, if they so desired, to have the talks all the same. -

Mother S Institut

MOTHER S INSTITUT Supermind in the Integral Yoga Problem of Ignorance, Bondage, Liberation and Perfection This book is addressed to all young people who, I urge, will study and respond to �he following message of Sri Aurobindo: "It is the young who must be the builders of the new world, - not those who accept the competitive individualism, the capitalism or the materialistic communism of the West as India's future ideal, nor those who are enslaved to old religious formulas and cannot believe in the acceptance and transformation of life by the spirit, but all those who are free in mind and heart to accept a completer truth and labour for a greater ideal. They must be men who will dedicate themselves not to the past or the present but to the future. They will need to consecrate their lives to an acceding of their lower self, to the realisation of God in themselves and in all human beings and to a whole-minded and indefatigable labourfor the nation and for humanity." (Sri Aurobindo, 'The Supramental Manifestation Upon Earth' Vol. 16, SABCL, p.331) Dedicated to Sri Aurobindo and the Mother SUPERMIND IN THE INTEGRAL YOGA PROBLEM OF IGNORANCE. BONDAGE, LIBERATION AND PERFECTION KlREET JOSHI The Mother's Institute of Research, New Delhi. [email protected] ©The Mother's Institute of Research All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without written permission of the author or the publisher. First edition, 2009 ISBN: 978-81-89490-12-7 Distributor : Popular Media, Delhi E: [email protected] www.popularmedia.in Cover-design : Macro Graphics Pvt. -

The Eschatology of Sri Aurobindo's Evolutionary' Doctrine

TRE ESCHATOLOGY OF SRI AUROBINDO'S EVOLUTIONARY DOCTRINE THE ESCHATOLOGY OF SRI AURO BIND 0 , S EVOLUTIONARY DOCTRINE By . .. -- ·_··-LOUIS THOM.A_S 0' NEIL, Ph, B • A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillmen.t of the Requirements for.the Degree Master of Arts MCMaster University April 1971 --MASTER OF --ARTS (1971) Mcr~STER UNIVERSITY (Religion) Hamilton, Ontario. TITLE: The Eschatology of Sri Aurobindo's Evolutionary' Doctrine AUTHOR: Louis Thomas O'Neil, Ph.B. (University of North Dakota) SUPERVISOR: Professor J. G. Arapura NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 108 ii PREFACE The approach taken in this thesis is to review closely the evolutionary doctrine of Sri Aurobindo. The object of writing a thesis of this nature is to point out the attempt of Aurobindo to go beyond the East and the West with a new understanding of evolution and the meaning of man. This new understanding has been presented from the point of view of Aurobindo and his followers. I have concentrated on the development within his system of his eschaton, this eschaton being what Aurobindo calls the divine life. His system is an attempt at synthesis and as such it deserves attention by all who consider themselves students of religion. I am deeply indebted to the suggestions and critical comments of Dr. J. G. Arapura. Also I wish to thank my wife Jeanie without whose assistance this thesis would not have been possible. iii --"""TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE iii CHAPTER 1 Introduction 1 Sri Aurobindo's Relation to th.e West and East CHAPTER 2 Aurobindo's -

June 2003, and Remember Him in Fondness the Whole Material Side of the Ashram, the Ashram Would and Be Grateful for All That He Has Done for Them and for Us

1 SABDA Newsletter Recent Publications he Mother used to have meetings with some of Tthe disciples in 1928 in the “Prosperity” Room in the Library House. Both Dyuman and I belonged to that group. Once the Mother raised the question: “Who among you has progressed the most during the past year?” The answer would not mean which sadhak or sadhika was the most advanced in general. It would declare which one had taken the most marked step forward during the preceding twelve months. While recollecting this question, I turned to Dyuman and asked whether it had struck in his memory too. He said “Yes”. Then I asked him whether he recalled the answer. He looked at me but kept quiet. I smiled and said: “We thought of Nolini, Amrita, Champaklal, Pavitra and Anilbaran, all old timers. But the Mother named you.” Dyuman’s face beamed and he exclaimed: “So you remember this?” I replied: “Who could forget so great a compliment?” Dyumanbhai in the 1940s — Amal Kiran CONTENTS Dyuman “The Luminous” — Karmayogi 2 The Renaissance: Notes and Papers 20 r Immortality 9 The Birth of Savit 21 Creation? Evolution? Or Both? 10 Brahman and Sri Aurobindo’s Integral Approach to the Upanishads 23 Recent Publications 11 Is Velikovsky’s Revised Chronology Tenable? 24 Ordering Information 16 An Interview with Nirodbaran/Selected Essays Reviews and Talks of Nirodbaran 25 Emergence of the Psychic 17 Amal Kiran on Nirodbaran 26 The Wonder that is Sanskrit 18 The Collected Works of the Mother 28 Bhavasumam 19 SABDA Newsletter 2 DYUMAN “THE LUMINOUS” — Karmayogi Krishna Chakravarti Dyuman-da or Dyumanbhai, as he was popularly known, was was reflected clearly in a letter written by Sri Aurobindo one of the sadhaks who moulded himself in the light of Sri in 1936 when replying to an inmate of the Ashram: “If Aurobindo and the Mother. -

Education and the Aim of Human Life

EDUCATION AND THE AIM OF HUMAN LIFE CONTENTS Education and the Aim of Human Life Introduction I. The Purpose of Education II. The Conception of Progress and the Present World Crisis III.. The Dawning of a New Age IV. Sri Aurobindo's Integral Education What is an Integral Education? The Physical Education The Vital Education The Mental Education The Psychic and the Spiritual Education Sri Aurobindo International Centre of education The Student's Prayer Our New System of Education (The Free Progress System) I. How the Child Educates Himself II. The Needs of the Child III. The Educational Environment IV.. The Class Work A. Collective Teaching B. Individual Work C. Team Work V. A Valuation of the New System VI. The Evolution of a Class VII.. The Task of the Educator VIII. Do We Need a New System of Education? Two Cardinal Points of Education Bibliography Notes and Sources Bibliographical Note by PAVITRA (P. B. Saint-Hilaire) Publisher's Note This book is a study of the educational ideal of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother and of the educational method being developed at the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education. Its author, Pavitra, was the first director of the Centre of Education. In the first section of the book he affirms the need of an "integral" education - one aimed at developing all the faculties of the human being, including the soul and spirit - and outlines the character of such an education. In the second section he explains the new system being attempted at the Centre of Education. In the third he summarises the educational theory and method of the Centre of Education. -

Mother India

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE Vol. LVI No. 3 “Great is Truth and it shall prevail” CONTENTS Sri Aurobindo O BEAUTIFUL BODY OF THE INCARNATE WORD (Poem) ... 179 THE PRESENT CRISIS AND ITS SOLUTION ... 181 THERE SHALL MOVE ON THE EARTH... (Poem) ... 186 SOME LETTERS ... 187 Arjava MOON-PROMPTED (Poem) ... 190 The Mother CONCENTRATION ... 191 PROPER CONDUCT ... 193 THREE CONCEPTIONS OF THE WORLD ... 196 Nolini Kanta Gupta THE SITUATION OF TODAY ... 197 Peter Heehs, Amal Kiran, Lalita INTERVIEW OF 8 SEPTEMBER 1979 ... 200 Yvonne Artaud OUR MOTHER ... 204 Arun Vaidya THE MOTHER’S MISSION — DIVINITY IN ACTION ... 205 Richard Hartz THE COMPOSITION OF SAVITRI ... 210 Debashish Banerji NIRODBARAN’S SURREALIST POEMS ... 216 Narad TRANSFORMING THE STREETS OF PONDICHERRY ... 218 Manmohan Ghose AUTUMN (Poem) ... 220 Krishna Chakravarti GLORY TO THE LUMINOUS ONE! ... 222 Roger Calverley PAIN (Poem) ... 224 B. G. Pattegar GOD’S SURRENDER ... 225 Balvinder Banga IN SRI AUROBINDO’S ROOM (Poem) ... 226 Kailas Jhaveri REMEMBRANCE OF THE MOTHER ... 227 Kati Widmer INTIMATE PORTRAITS ... 233 Goutam Ghosal TAGORE AND SRI AUROBINDO ... 238 Ranajit Sarkar THE RELATION BETWEEN THE POETIC ACT AND THE AESTHETIC EXPERIENCE ... 240 R. Y. Deshpande ISLAM’S CONTRIBUTION TO SCIENCE ... 244 M. S. Srinivasan RELEVANCE OF SRI AUROBINDO’S VISION FOR THE EMERGING TECHNOLOGICAL SCENE ... 251 Sunil Behari Mohanty EDUCATIONAL IDEAS OF SWAMI DAYANAND ... 254 Mary Helen ACROSS THE IMAGED VASTS (Poem) ... 259 Indra Sen SRI AUROBINDO AND MAYAVADA ... 260 BOOKS IN THE BALANCE Nilima Das Review of CHAMPAKLAL SPEAKS edited by M. P. PANDIT AND revised by ROSHAN ... 266 179 O BEAUTIFUL BODY OF THE INCARNATE WORD O BEAUTIFUL body of the incarnate Word, Thy thoughts are mine, I have spoken with thy voice…. -

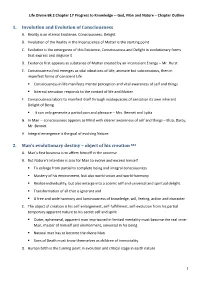

1. Involution and Evolution of Consciousness 2

Life Divine Bk 2 Chapter 17 Progress to Knowledge -- God, Man and Nature – Chapter Outline 1. Involution and Evolution of Consciousness A. Reality is an eternal Existence, Consciousness, Delight B. Involution of the Reality in the Inconscience of Matter is the starting point C. Evolution is the emergence of this Existence, Consciousness and Delight in evolutionary forms that express and disguise it. D. Existence first appears as substance of Matter created by an inconscient Energy – Mr. Hurst E. Consciousness first emerges as vital vibrations of Life, animate but subconscious, then in imperfect forms of conscient Life . Consciousness in life manifests mental perception and vital awareness of self and things . Internal sensation responds to the contact of life and Matter F. Consciousness labors to manifest itself through inadequacies of sensation its own inherent Delight of Being . It can only generate a partial pain and pleasure – Mrs. Bennet and Lydia G. In Man -- consciousness appears as Mind with clearer awareness of self and things – Eliza, Darcy, Mr. Bennet H. Integral emergence is the goal of evolving Nature 2. Man’s evolutionary destiny – object of his creation 684 A. Man’s first business is to affirm himself in the universe B. But Nature’s intention is also for Man to evolve and exceed himself . To enlarge from partial to complete being and integral consciousness . Mastery of his environment, but also world-union and world-harmony . Realize individuality, but also enlarge into a cosmic self and universal and spiritual delight. Transformation of all that is ignorant and . A free and wide harmony and luminousness of knowledge, will, feeling, action and character C. -

Mother India

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE Vol. LIX No. 9 “Great is Truth and it shall prevail” CONTENTS Sri Aurobindo THE GUEST (Poem) ... 689 SUPERMIND AND HUMANITY ... 690 The Mother ‘WE MUST SHAKE OFF THE PAST’ ... 697 A FUTURE ... WHICH HAS BEGUN ... 698 51. FROM THE CONVERSATION OF 24 JULY 1957 ... 698 52. FROM THE CONVERSATION OF 7 AUGUST 1957 ... 700 53. FROM THE CONVERSATION OF 21 AUGUST 1957 ... 703 54. FROM THE CONVERSATION OF 28 AUGUST 1957 ... 705 Amal Kiran (K. D. Sethna) CORRESPONDENCE ON POETRY ... 707 Hemant Kapoor NIRODBARAN: DIVINITY’S COMRADE ... 710 Nirodbaran SLEEP OF LIGHT (Poem) ... 717 Chitra Sen WASHING OF SRI AUROBINDO’S CLOTHES ... 718 Ram Sehgal DR. VENKATASWAMY ... 721 Arabinda Basu TOWARDS HARMONY OF CULTURES ... 723 S. V. Bhatt PAINTING AS SADHANA: KRISHNALAL BHATT (1905-1990) ... 730 M. S. Srinivasan HISTORY OF THE FUTURE ... 737 Narad (Richard Eggenberger) NARAD REMEMBERS: THÉMIS—THE POET ... 746 Ranajit Sarkar DUTCH PAINTING IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ... 751 Hemant Kapoor REPLY (Poem) ... 756 Priti Das Gupta MOMENTS, ETERNAL ... 757 Gopika SILENT RENEWAL (Poem) ... 766 Prema Nandakumar DEVOTIONAL POETRY IN TAMIL ... 767 Kripa Anuru THE STORM AND BEYOND (Poem) ... 775 Gary PANCHASSEE-MOUNTAIN ... 776 689 THE GUEST I have discovered my deep deathless being: Masked by my front of mind, immense, serene, It meets the world with an Immortal’s seeing, A god-spectator of the human scene. No pain and sorrow of the heart and flesh Can tread that pure and voiceless sanctuary. Danger and fear, fate’s hounds, slipping their leash Rend body and nerve,—the timeless Spirit is free. -

Mountain Path

,,»,»•« »••••••»»••>»•••«•>• < y»»»«»#»«•»••••••»»•••••»•• * % •••«»»»••»••••••••••>•><1 iMMtlillMMIiMIMIMi <| llltlMIIMIIIMIIIM • ) MH M Itl I I ! I I I t II I '«»»»»#»!••»»«•»»»> I I It I I I I I I II I > 'MIIIIMIII 'IIIIIIIIH • «•«•• I I ( *»••»•»» HI»»•• I I .i» * • * » i « • I 3^ V1 Arunachala! Thou dost root out the ego of those who meditate on Thee in the heart, Oh Arunachala/ The Mountain Path Vol. IV JANUARY 1967 No. 4 SRI RAM AN AS-RAM AM, TIRU VAN N AMALAI " Significance of OM unrivalled — unsurpassed ! Who can comprehend Thee, Oh Arunachala ! " (A QUARTERLY) —The Marital Garland of Letters, verse 13. " Arunachala ! Thou dost root out the ego of those who meditate on Thee in the heart, Oh Arunachala ! " —The Marital Garland of Letters, verse 1. Publisher : JANUARY 1967 No. 1 T. N. Venkataraman, Vol. IV Sri Ramanasramam, Tiruvannamalai. CONTENTS Page EDITORIAL I The Problem of Suffering 1 Sorrow — ' Alone ' 4 Editor : Bhagavan on Suffering 5 Arthur Osborne, The Four Noble Truths — Bodhichitta 8 Suffering, its cause and cure, according Sri Ramanasramam, to the Isha Upanishad — Madguni Tiruvannamalai. Shambhu Bhat 10 Theory and practice according to Sri Ramana — N. Ramasubramanyam 11 The Nature and Significance of Tap as — G. V. Kulkarni 12 Vicarious Suffering — /. Jesudasan, SJ. 16 In Brief — G. N. Daley 22 Managing Editor : ASPECTS OF ISLAM - XII I V. Ganesan, " Which, then of your Lord's bounties Sri Ramanasramam, will you reject ? " Tiruvannamalai. — A bdullah Qutbuddin 23 ARROWS FROM A CHRISTIAN BOW - XIII : The Cult of Suffering — Sagittarius 25 Minnows in the Seven Seas — An Anonymous Annual Subscription : Seeker 27 Pain and Pleasure — Prof. -

Winter 2018/2019, Vol. 43, No. 3

Winter 2018/2019 Journal of the Integral Yoga of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother Vol. 43, No. 3 Matrimandir Meditations and the Matrimandir by Julie of Light Omega • On attending a Savitri workshop by Kannappan Singaram • Reflections on faith by Seabury Gould• From vairagya to gifts and blessings, Interview of Lucas by Matthias Pommerening • Central processes and practices in Integral Yoga by Larry Seidlitz • Conscious individuality by James Anderson • Current affairs • AV almanac • Source material • Book review • The poetry room • Apropos Winter 2018/2019 Collaboration • 1 About the art on the front and back cover Table of contents Front cover: “Dalhia,” by Soleil Aurose (see Collaboration, Vol. 43, No. 3, Winter 2018/2019 note on the artist on p. 3). Back cover: “Children’s Imagination,” by Yuriy Mazur (from Adobe stock photos), offers From the office of Collaboration a glimpse into the child-like wonder of peering into the beauty and mystery of the Divine. Notes on this issue ..................................................................................... 3 The authors and poets Current affairs Alan ([email protected]), an Aurovilian, is a teacher and co-editor of Auroville Today. Passing of Rudy Phillips ..................................................... Julian Lines 4 James Anderson (jamie_randers@hotmail. 2019 Integral Yoga Retreat in Greenville, SC .....................Radhe Pfau 4 com) is a sadhak residing in Pondicherry and an Integral Yoga Retreat at Madhuban ............................... Amit Thakkar 4 editor of NAMAH, a journal on integral health. Aravinda ([email protected]) Activities at Sri Aurobindo Center, Los Angeles ............. Jishnu Guha 5 is an Aurovilian of Indian birth. He went to the About the website motherandsriaurobindo.in ...........................Narad 5 Ashram School and then spent time in South Africa.