Stock Options at Caldera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Megaraid 6Gb/S SAS RAID Controllers Users Guide

USER’S GUIDE MegaRAID® 6Gb/s SAS RAID Controllers November 2009 41450-02 Rev. B This document contains proprietary information of LSI Corporation. The information contained herein is not to be used by or disclosed to third parties without the express written permission of an officer of LSI Corporation. LSI products are not intended for use in life-support appliances, devices, or systems. Use of any LSI product in such applications without written consent of the appropriate LSI officer is prohibited. Purchase of I2C components of LSI Corporation, or one of its sublicensed Associated Companies, conveys a license under the Philips I2C Patent Rights to use these components in an I2C system, provided that the system conforms to the I2C standard Specification as defined by Philips. Document 41450-02 Rev. B, November 2009. This document describes the current versions of the LSI Corporation MegaRAID® SAS RAID controllers and will remain the official reference source for all revisions/releases of these products until rescinded by an update. LSI Corporation reserves the right to make changes to any products herein at any time without notice. LSI does not assume any responsibility or liability arising out of the application or use of any product described herein, except as expressly agreed to in writing by LSI; nor does the purchase or use of a product from LSI convey a license under any patent rights, copyrights, trademark rights, or any other of the intellectual property rights of LSI or third parties. Copyright © 2009 by LSI Corporation. All rights reserved. TRADEMARK ACKNOWLEDGMENT LSI, the LSI logo design, Fusion-MPT, and MegaRAID are trademarks or registered trademarks of LSI Corporation. -

Current Status of OFED in SUSE Linux Enterprise Server

Current Status of OFED in SUSE Linux Enterprise Server John Jolly Senior Software Engineer SUSE Agenda 2 λAbout SUSE λAbout SUSE Linux Enterprise Server λOFED Integration into SLES λFuture Direction of OFED in SLES SUSE and the Attachmate Group λSUSE , headquartered in Nürnberg / Germany, λis an independently operating business unit of λThe Attachmate Group, Inc. λThe Attachmate Group is a privately held λ1 billion+ $ revenue software company λwith four brands: •Cloud Infrastructure •Enterprise Computing •Integrated Systems SUSE® Linux Enterprise How We Build It Online Repository Source Package Image OBS OBS user submits source to OBS and gets a product SUSE® Linux Enterprise Server 12 Lifecyle Model •13-year lifecycle (10 years general support, 3 years extended support) •5-year lifecycle per Service Pack (2 years general + 3 years extended support) •Long Term Service Pack Support (LTSS) available for all versions, including GA http://www.suse.com/lifecycle/ Unique Tools Included λAppArmor Security Framework -Application confinement λFree High Availability Extension -Cluster Framework, Cluster FS, DRBD, GEO-cluster* λYaST2 systems management -Install, deploy, and configure every aspect of the server λSubscription Management Tool -Subscription and patch management, proxy/mirroring/staging λStarter System for System z -A pre-built installation server, deployable with z/VM tools Features of SLES 12 λLinux Kernel 3.12 λOnly 64-bit kernel -Support of 32-bit application through execution environment λYaST modules written in Ruby λOFED 3.12 -Significant -

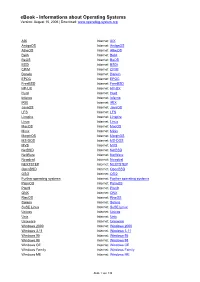

Ebook - Informations About Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download

eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org AIX Internet: AIX AmigaOS Internet: AmigaOS AtheOS Internet: AtheOS BeIA Internet: BeIA BeOS Internet: BeOS BSDi Internet: BSDi CP/M Internet: CP/M Darwin Internet: Darwin EPOC Internet: EPOC FreeBSD Internet: FreeBSD HP-UX Internet: HP-UX Hurd Internet: Hurd Inferno Internet: Inferno IRIX Internet: IRIX JavaOS Internet: JavaOS LFS Internet: LFS Linspire Internet: Linspire Linux Internet: Linux MacOS Internet: MacOS Minix Internet: Minix MorphOS Internet: MorphOS MS-DOS Internet: MS-DOS MVS Internet: MVS NetBSD Internet: NetBSD NetWare Internet: NetWare Newdeal Internet: Newdeal NEXTSTEP Internet: NEXTSTEP OpenBSD Internet: OpenBSD OS/2 Internet: OS/2 Further operating systems Internet: Further operating systems PalmOS Internet: PalmOS Plan9 Internet: Plan9 QNX Internet: QNX RiscOS Internet: RiscOS Solaris Internet: Solaris SuSE Linux Internet: SuSE Linux Unicos Internet: Unicos Unix Internet: Unix Unixware Internet: Unixware Windows 2000 Internet: Windows 2000 Windows 3.11 Internet: Windows 3.11 Windows 95 Internet: Windows 95 Windows 98 Internet: Windows 98 Windows CE Internet: Windows CE Windows Family Internet: Windows Family Windows ME Internet: Windows ME Seite 1 von 138 eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org Windows NT 3.1 Internet: Windows NT 3.1 Windows NT 4.0 Internet: Windows NT 4.0 Windows Server 2003 Internet: Windows Server 2003 Windows Vista Internet: Windows Vista Windows XP Internet: Windows XP Apple - Company Internet: Apple - Company AT&T - Company Internet: AT&T - Company Be Inc. - Company Internet: Be Inc. - Company BSD Family Internet: BSD Family Cray Inc. -

Caldera Systems to Acquire Sco Server Software

CALDERA SYSTEMS TO ACQUIRE SCO SERVER SOFTWARE AND PROFESSIONAL SERVICESDIVISIONS, PROVIDING WORLD'S LARGEST LINUX /UNIX CHANNEL Submitted by: Archetype (Text100) Wednesday, 2 August 2000 Offers First Open Internet Platform, Embracing Open Access to Linux and UNIX Technologies OREM, UT - August 2, 2000 - Caldera Systems, Inc., (Nasdaq: CALD), a "Linux for Business" leader and The Santa Cruz Operation, Inc., (SCO) (Nasdaq: SCOC), the world's leading provider of UNIX operating systems, today announced that Caldera Systems has entered into an agreement to acquire the SCO Server Software Division and the Professional Services Division. The Professional Services Division will operate as a separate business unit of Caldera, to provide services to meet the Internet and eBusiness infrastructure needs of customers. The new company will offer the industry's first comprehensive Open Internet Platform (OIP) combining Linux and UNIX server solutions and services globally. The OIP provides commercial customers and developers with a single platform that can scale from the thinnest of clients to the clustering needs of the largest data center. The Open Internet Platform combines the robust scalability of the UNIX system with the low-cost, developer-accepted Linux operating system. The products, solutions, and services developed for the Open Internet Platform will be available through more than 15,000 partners worldwide. Details of the Agreement Caldera Systems, Inc. will form a new holding company, Caldera, Inc., to acquire assets from the SCO Server Software Division plus the SCO Professional Services Division, including a highly skilled workforce, products and channel resources. Caldera, Inc. will have exclusive distribution rights for the SCO OpenServer product line, and is fully committed to servicing and supporting the SCO OpenServer customer base. -

SUSE® Linux Enterprise Server ("SLES ™")11 SP1 Novell® Software License Agreement

SUSE® Linux Enterprise Server ("SLES ™")11 SP1 Novell® Software License Agreement PLEASE READ THIS AGREEMENT CAREFULLY. BY INSTALLING OR OTHERWISE USING THE SOFTWARE (INCLUDING ITS COMPONENTS), YOU AGREE TO THE TERMS OF THIS AGREEMENT. IF YOU DO NOT AGREE WITH THESE TERMS, DO NOT DOWNLOAD, INSTALL OR USE THE SOFTWARE. RIGHTS AND LICENSES This Novell Software License Agreement (“Agreement”) is a legal agreement between You (an entity or a person) and Novell, Inc. (“Novell”). The software product identified in the title of this Agreement, any media and accompanying documentation (collectively the “Software”) is protected by the copyright laws and treaties of the United States (“U.S.”) and other countries and is subject to the terms of this Agreement. Any update or support release to the Software that You may download or receive that is not accompanied by a license agreement expressly superseding this Agreement is Software and governed by this Agreement. If the Software is an update or support release, then You must have validly licensed the version and quantity of the Software being updated or supported in order to install or use the update or support release. The Software is a modular operating system comprised of numerous components that may be accompanied by separate license terms. The Software is a collective work of Novell; although Novell does not own the copyright to every component of the Software, Novell owns the collective work copyright for the Software. Most of the components are open source packages, developed independently, and accompanied by separate license terms. Your license rights with respect to individual components accompanied by separate license terms are defined by those terms; nothing in this agreement shall restrict, limit, or otherwise affect any rights or obligations You may have, or conditions to which You may be subject, under such license terms; however, if You distribute copies of any component independent of the Software, You must remove all Novell trademarks, trade dress, and logos from each copy. -

Open Source Legal Risk Management in the Enterprise, Version 1.2 - 2 of 7

Open Source Legal Risk Management in the Enterprise, Version 1.2 OPTAROS WHITE PAPER Realize the Benefits of Open Source Open Source Legal Risk Management in the Enterprise, Version 1.2 - 2 of 7 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2 SCO Group vs. IBM............................................................................................................................ 2 License Management and Compliance .................................................................................................. 3 Patents and Property ......................................................................................................................... 4 Indemnification and Insurance ............................................................................................................ 5 Summary......................................................................................................................................... 6 About the Author Stephen Walli........................................................................................................... 7 About Optaros .................................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction There is sometimes confusion about how legally risky using free and open source software (FOSS) can be in the enterprise. These concerns center around: ♦ the SCO Group vs. IBM lawsuit, ♦ -

United States Court of Appeals for the FOURTH CIRCUIT

Case: 10-1482 Document: 35 Date Filed: 09/17/2010 Page: 1 No. 10-1482 IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT dNOVELL, INCORPORATED, Plaintiff-Appellant, —v.— MICROSOFT CORPORATION, Defendant-Appellee. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND BRIEF OF APPELLEE MICROSOFT CORPORATION RICHARD J. WALLIS DAVID B.TULCHIN STEVEN J. AESCHBACHER Counsel of Record MICROSOFT CORPORATION STEVEN L. HOLLEY One Microsoft Way SULLIVAN & CROMWELL LLP Redmond, Washington 98052 125 Broad Street (425) 882-8080 New York, New York 10004 (212) 558-4000 G. S TEWART WEBB VENABLE LLP 750 East Pratt Street, Suite 900 Baltimore, Maryland 21202 (410) 244-7400 Attorneys for Microsoft Corporation September 17, 2010 Case: 10-1482 Document: 35 Date Filed: 09/17/2010 Page: 2 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATIONS AND OTHER INTERESTS Only one form needs to be completed for a party even if the party is represented by more than one attorney. Disclosures must be filed on behalf of all parties to a civil, agency, bankruptcy or mandamus case. Corporate defendants in a criminal or post-conviction case and corporate amici curiae are required to file disclosure statements. Counsel has a continuing duty to update this information. No. _______ Caption: __________________________________________________ Pursuant to FRAP 26.1 and Local Rule 26.1, ______________________ who is _______________________, makes the following disclosure: (name of party/amicus) (appellant/appellee/amicus) 1. Is party/amicus a publicly held corporation or other publicly held entity? YES NO 2. Does party/amicus have any parent corporations? YES NO If yes, identify all parent corporations, including grandparent and great-grandparent corporations: 3. -

Engineering Law and Ethics

ENSC 406 Software, Computer and Internet Ethics Bob Gill, P.Eng., FEC, smIEEE May 15th 2017 1 Topics Covered What is Open Source Software? A One-Slide History of Open Source Software The Open Source Development Model Why Companies Use (and Don’t Use) Open Source Software Open Source Licensing Strategies Open Source Licenses and “Copyleft” Open Source Issues in Corporate Transactions Relevant Cases and Disputes Open source vs. Freeware vs. Shareware Site Licensing Software Maintenance Computer and Internet Ethics 2 What is Open Source Software? Open Source software is software licensed under an agreement that conforms to the Open Source Definition Access to Source Code Freedom to Redistribute Freedom to Modify Non-Discriminatory Licensing (licensee/product) Integrity of Authorship Redistribution in accordance with the Open Source License Agreement 3 What is Open Source Software? Any developer/licensor can draft an agreement that conforms to the OSD, though most licensors use existing agreements GNU Public License (“GPL”) Lesser/Library GNU Public License (“LGPL”) Mozilla Public License Berkeley Software Distribution license (“BSD”) Apache Software License MIT – X11 License See complete list at www.opensource.org/licenses 4 Examples of Open Source Software Linux (operating system kernel – substitutes for proprietary UNIX) Apache Web Server (web server for UNIX systems) MySQL(Structured Query Language – competes with Oracle) Cloudscape, Eclipse (IBM contributions) OpenOffice(Microsoft Office Alternate) SciLab, -

SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11 SP4 System Analysis and Tuning Guide System Analysis and Tuning Guide SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11 SP4

SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11 SP4 System Analysis and Tuning Guide System Analysis and Tuning Guide SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11 SP4 Publication Date: September 24, 2021 SUSE LLC 1800 South Novell Place Provo, UT 84606 USA https://documentation.suse.com Copyright © 2006– 2021 SUSE LLC and contributors. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or (at your option) version 1.3; with the Invariant Section being this copyright notice and license. A copy of the license version 1.2 is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. For SUSE trademarks, see http://www.suse.com/company/legal/ . All other third party trademarks are the property of their respective owners. A trademark symbol (®, ™ etc.) denotes a SUSE or Novell trademark; an asterisk (*) denotes a third party trademark. All information found in this book has been compiled with utmost attention to detail. However, this does not guarantee complete accuracy. Neither SUSE LLC, its aliates, the authors nor the translators shall be held liable for possible errors or the consequences thereof. Contents About This Guide xi 1 Available Documentation xii 2 Feedback xiv 3 Documentation Conventions xv I BASICS 1 1 General Notes on System Tuning 2 1.1 Be Sure What Problem to Solve 2 1.2 Rule Out Common Problems 3 1.3 Finding the Bottleneck 3 1.4 Step-by-step Tuning 4 II SYSTEM MONITORING 5 2 System Monitoring Utilities 6 2.1 Multi-Purpose Tools 6 vmstat 7 -

Wikipedia: Design of the FAT File System

Design of the FAT file system A FAT file system is a specific type of computer file system architecture and FAT a family of industry-standard file systems utilizing it. Developer(s) Microsoft, SCP, IBM, [3] The FAT file system is a legacy file system which is simple and robust. It Compaq, Digital offers good performance even in very light-weight implementations, but Research, Novell, cannot deliver the same performance, reliability and scalability as some Caldera modern file systems. It is, however, supported for compatibility reasons by Full name File Allocation Table: nearly all currently developed operating systems for personal computers and FAT12 (12- many home computers, mobile devices and embedded systems, and thus is a bit version), well suited format for data exchange between computers and devices of almost FAT16 (16- any type and age from 1981 through the present. bit versions), Originally designed in 1977 for use on floppy disks, FAT was soon adapted and FAT32 (32-bit version used almost universally on hard disks throughout the DOS and Windows 9x with 28 bits used), eras for two decades. Today, FAT file systems are still commonly found on exFAT (64- floppy disks, USB sticks, flash and other solid-state memory cards and bit versions) modules, and many portable and embedded devices. DCF implements FAT as Introduced 1977 (Standalone the standard file system for digital cameras since 1998.[4] FAT is also utilized Disk BASIC-80) for the EFI system partition (partition type 0xEF) in the boot stage of EFI- FAT12: August 1980 compliant computers. (SCP QDOS) FAT16: August 1984 For floppy disks, FAT has been standardized as ECMA-107[5] and (IBM PC DOS 3.0) ISO/IEC 9293:1994[6] (superseding ISO 9293:1987[7]). -

DR DOS for the Zfx86

DR DOS for the ZFx86 Cost Effective, Reliable, Rapid Deployment of Embedded Systems w DR DOS on the ZFx86 gets products to market quickly at the lowest development and ownership cost. w Thousands of compatible applications, drivers and utilities available free or at minimal cost. w Full documentation available. DR DOS 7.03 Key Features of DR DOS Online Manual - DRDOS is supplied with a complete The ideal embedded DOS system, online manual that contains detailed information about all designed for out-of-the-box of the features of the operating system including the basic implementation into ROM or Flash commands, and the advanced utilities. It also has online ROM with tools and associated help available for all its commands. documents available in the DRDOS Memory Management - Memory management features OEM Documentation Kit. include a set of device drivers and commands that enable w 100% MS-DOS 6.22 compatible.. you to manage memory efficiently and make as much memory as possible available to your applications. w Comprehensive DOS utility set DOS Protected Mode Services - DOS Protected Mode w Multitasking, with API for developers Services (DPMS) interface allows specially-implemented w DPMS memory manager in addition to DPMI device drivers and TSRs to operate in extended memory. w Stacker disk compression This makes more memory within the first megabyte w NWCACHE - disk caching program available to applications and other conventionally-written drivers and TSRs. Both Stacker* (the disk compression w EMM386 memory manager program), and NWCACHE (the disk cache) use DPMS. w DOS Protected Mode Services (DPMS) Disk Compression - The disk compression component w Multitasking enables you to store more information by compressing the w DR-DOS provides a full multitasking environment data. -

Govt Linux Appreciation Day 09/18/01

John Terpstra Vice President, Technology Caldera International, Inc. The Maturation of Linux Are we there yet? Slide 2 The Road to Maturity . Self-Discipline . Acceptance of Responsibility . Accountability for Actions Slide 3 MarketMarket Share 1999 Worldwide Market for Server Operating Environments N = 5.475 Million Shipments Other NOS Netware 2.6% 19.4% NT Server 38.1% Unix & Linux 39.9% Source: IDC Slide 4 Linux Server Applications Primary Function of Linux Servers Installed at U.S. Sites, 1999 Web Server 42.1% Overwhelming File/Print Server 26.0% appeal as a Web Email Server 23.2% DNS 15.3% server – over 50% Firewall/Proxy/Cache 14.7% of all Internet Internet/Intranet Server 12.6% Web Servers run Database 10.5% on Apache and Application Development 8.4% Application server 6.3% 60% of all Apache Experimental/Testing 6.3% Servers run on Router/Gateway 5.8% Linux Networking 2.6% Systems Mgmt. 2.1% Backup 2.1% VPN 1.6% Technical Apps 1.1% Other 1.1% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% Source: IDC N=195 Slide 5 Where Are We? 1. File and Print – 10 Million servers - Major application - Samba 2. Web Serving – 18 Million servers - Major application - Apache 3. Proxy Serving - - Major application – Squid Linux plays a major role hosting each application Slide 6 A Competitive View – Then http://www.microsoft.com/windows/serverappliance/kempin.asp Date: Nov 9, 2000 But it is true that Linux are actually rapidly increasing their market share in the US also. Doesn't this pose a threat? "Linux is simply a fad that has been generated by the media and is destined to fall by the wayside in time.