With This Beautifully Produced Volume, Chicago's Rich Literary Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Gwendolyn Brooks 1917–2000

Name _____________________________ Class _________________ Date __________________ The Civil Rights Movement Biography Gwendolyn Brooks 1917–2000 WHY SHE MADE HISTORY Gwendolyn Brooks was an award-winning poet, novelist, and a leader of the Black Arts Movement. She was also the first African American poet to receive a Pulitzer Prize. As you read the biography below, think about the role Gwendolyn Brooks’ writing played in the civil rights movement. Why was her poetry significant? Bettmann/CORBIS © As African Americans worked to bring an end to discrimination, most still lived in poor inner city neighborhoods. The Black Power movement focused on the need for social and economic reforms. A Black Arts Movement also emerged to tell the story of African American life. Poet Gwendolyn Brooks was at the forefront of this movement. Gwendolyn Brooks was born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1917. Two months after her birth, her family moved to Chicago, Illinois, where she would live for the rest of her life. Brooks was a shy child who developed an interest in writing. Her mother encouraged this interest, and teachers helped develop her talent. At an early age, Brooks was published in national magazines and newspapers. After graduation from high school, Brooks entered community college and received an associate’s degree. She worked at many different jobs, from maid to spiritual healer. Later she would write about these experiences. She was also involved in the Youth Council of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and helped found a club for young black artists and writers. Through this club, she met her future husband, poet Henry Blakely. -

The Newberry Annual Report 2019–20

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2019–20 30 Fall/Winter 2020 Letter from the Chair and the President Dear Friends and Supporters of the Newberry, The Newberry’s 133rd year began with sweeping changes in library leadership when Daniel Greene was appointed President and Librarian in August 2019. The year concluded in the midst of a global pandemic which mandated the closure of our building. As the Newberry staff adjusted to the abrupt change of working from home in mid-March, we quickly found innovative ways to continue engaging with our many audiences while making Chair of the Board of Trustees President and Librarian plans to safely reopen the building. The Newberry David C. Hilliard Daniel Greene responded both to the pandemic and to the civil unrest in Chicago and nationwide with creativity, energy, and dedication to advancing the library’s mission in a changed world. Our work at the Newberry relies on gathering people together to think deeply about the humanities. Our community—including readers, scholars, students, exhibition visitors, program attendees, volunteers, and donors—brings the library’s collection to life through research and collaboration. After in-person gatherings became impossible, we joined together in new ways, connecting with our community online. Our popular Adult Education Seminars, for example, offered a full array of classes over Zoom this summer, and our public programs also went online. In both cases, attendance skyrocketed, and we were able to significantly expand our geographic reach. With the Reading Rooms closed, library staff responded to more than 450 research questions over email while working from home. -

Villages Daily Sun Inks Press, Postpress Deals for New Production

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com September/October 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Villages Daily Sun inks press, postpress deals for new production facility u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER The Villages (Florida) Daily Sun is on the list of publishers which is nearer to Orlando. But with development trending as winning the good fight when it comes to community news- it is, Sprung said The Daily Sun will soon be at the center of the papering. The paper’s circulation is just over 60,000, and KBA Photo: expanded community. — thanks to rapid growth in the community — that number is steadily climbing. Some 120,000 people already call The Partnerships key Villages home, and approximately 300 new houses are being Choosing vendors to supply various parts of the workflow at built there every month. the new facility has been about forming partnerships, accord- To keep pace with the growth, The Daily Sun purchased a Pictured following the contract ing to Sprung. Cost is obviously a consideration, but success brand-new 100,000-square-foot production facility and new signing for a new KBA press in ultimately depends on relationships, he said — both with the Florida: Jim Sprung, associate printing equipment. The publisher is confident the investment publisher for The Villages Media community The Daily Sun serves and the technology providers will help further entrench The Daily Sun as the definitive news- Group; Winfried Schenker, senior who help to produce the printed product. paper publisher and printer in the region. -

Special Collections in the Public Library

ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Library Trends VOLUME 36 NUMBER 1 SUMMER 1987 University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science Whrre necessary, prrmisyion IS gr.inted by thr cop)right owncr for libraries and otherq registered with the Copyright Clearance Centrr (CXC)to photocop) any article herein for $5.00 pei article. Pay- ments should br sent dirrctly tn thr Copy- right Clraranrc Crnter, 27 Congiess Strert, Salem, blasaachusrtts 10970. Cop)- ing done for other than prrsonal or inter- nal reference usr-such as cop)iiig for general distribution, tot advertising or promotional purposrs. foi creating new collrctivc works, or for rraale-without the expressed permisyion of The Board of Trurtees of 'Thr University of Illinois is prohibited. Requests for special perrnis- sion or bulk orders should be addiessed to The GiaduateSrhool of L.ibrarv and Infor- mation Science, 249 Armory Building, 505 E Armory St., Champaizri, Illinois 61820. Serial-[re rodr: 00242594 87 $3 + .00. Copyright 6) 1987 Thr Board of Trusters of The Ilnivrisity of Illiiioia. Recent Trends In Rare Book Librarianship MICHELE VALERIE CLOONAN Issue Editor CONTENTS I. Recent Trends in Rare Book Librarianship: An Ormziiew Micht.le Valerie Cloonan 3 INTRODUCTION Sidney E. Berger 9 WHAT IS SO RARE...: ISSI ES N RARE BOOK LIBRARIANSHIP 11. Aduances in Scientific Investigation and Automation Jeffrey Abt 23 OBJECTIFYING THE BOOK: THE IMPACT OF- SCIENCE ON BOOKS AND MANUSCRIPTS Paul S. Koda 39 SCIENTIFIC: EQUIPMEN'I' FOR THE EXAMINATION OF RARE BOOKS, MANITSCRIPTS, AND DOCITMENTS Richard N. -

Women's History Month Children's Books.Pdf

Books for Family Sharing Charles, Tami. Fearless Mary: Mary Fields, American Stagecoach Driver. Illus. by Claire Almon. J-Biography 388.3228 FIEL Set in Cascade, Montana, in 1895, this rip-roaring account tells the true-life tale of a Wild West paragon—the first African American woman to drive a stagecoach while fearlessly fending off outlaws and wild critters to safely deliver the mail. Clinton, Chelsea. She Persisted: 13 American Women Who Changed the World. Illus. by Alexandra Boiger. J-Biography 305.40922 CLIN Concise text and warm watercolor illustrations introduce 13 inspiring women who "did not take no for an answer," including Ruby Bridges, Maria Tallchief, Sonia Sotomayor, and more. She Persisted Around the World and She Persisted In Sports offer more profiles of remarkable individuals. Engle, Margarita. Drum Dream Girl: How One Girl’s Courage Changed Music. Illus. by Rafael López. J-Easy Based on the childhood of musician Millo Castro Zaldarriaga, this lyrical picture book describes how a young girl in 1930s Cuba strived to become a drummer, though reminded again and again that only boys play percussion, and ultimately broke traditional stereotypes to follow her dream. Harrison, Vashti. Little Dreamers: Visionary Women Around the World. J-Biography 305.42 HARR Harrison’s one-page profiles and eye-catching portraits introduce 36 daring and resourceful women from throughout history and across the globe. Also check out the companion volume, Little Leaders: Bold Women in Black History. Hubbard, Rita Lorraine. The Oldest Student: How Mary Walker Learned to Read. Illus. by Oge Mora. J-Biography 306.3 WALK Born enslaved in 1848 on an Alabama plantation and freed at age 15, Walker grew into adulthood and worked hard for decades to support her family before taking a literacy class and learning to read at the age of 116. -

December 2006

Literary License December, 2006 AWARDS DEADLINE FEB. 15 Newsweek surveying the publishing scene. whim”–whatever her 45 reviewers happen Books published during 2006 may be What’s an author to do? to be interested in on a given day. She entered in the annual SMA awards contest To answer that question SMA presented throws out all press releases. She does until Feb. 15, 2007. a panel of experts at the Nov. 14 meeting in favor books from certain small publishers. Entries must be shipped directly to the the Chicago Athletic Association. She has responded to books with Post-It® judges in each category, Tom Ciesielka, professional book tabs calling attention to pages of special The list of judges and complete publicist and columnist for Literary interest. Good cover design can help. instructions will be posted soon on the License, observed that newspaper literary None of the panelists wanted any phone SMA web site: www.midland authors.com editors get as many as 50 books a day. calls. E-mails should explain in the first and published in the next issue of Literary Cheryl L. Reed, books editor of the paragraph what’s different about your License. Chicago Sun-Times, said she has only book. West considers such factors as the Information is available from Carol Jean “seconds to decide” which books to assign reputation of the author, the significance Carlson, awards chairman: 1420 W. for review. A brief handwritten note and timeliness of the subject. It’s OK to be Farragut Ave., Chicago, IL 60640. attached to the book and calling attention persistent and keep trying, but self- (D)773/275-3999 (N) 773/506-7578. -

Elizabeth Acevedo Kwame Alexander Maya Angelou Gwendolyn Brooks

Jacqueline Woodson is the author of nu- merous award-winning books, includ- POETS ing Last Summer With Maizon, I Hadn't Meant to Tell You This, From the Note- Elizabeth Acevedo* books of Melanin Sun, and Miracle's * Boys. She started writing when she was Kwame Alexander young, but her fiction for kids didn't real- Maya Angelou ly click until she got older. That's when she realized that she could actually help Gwendolyn Brooks the younger generation simply through Mahogany L. Browne her words. That's why Woodson chooses subjects Nikki Giovanni that she thinks kids should be able to Nikki Grimes read about — even if they're topics that are hard to explain or uncomfortable to Angela Johnson talk about. For example, If You Come Terrence Hayes Softly is about an interracial ro- mance; Hush tells the story of a family Langston Hughes placed under the witness protection pro- Tony Medina gram; and Sweet, Sweet Memory depicts the way a young girl copes with her Walter Dean Myers grandfather's death. Visiting Day is a pic- Marilyn Nelson ture book about a little girl's trips to see * her father in prison. Jason Reynolds www.jacquelinewoodson.com Faith Ringgold Jacqueline.Woodson Carole B. Weatherford * @jackiewoodson Jaqueline Woodson jacqueline_woodson Richard Wright * Read more about this author Playing the Read-In bingo game? on the following pages... Woodson has books in these categories: Poetry/Biography/Picture Book “This is what’s most important to me — to show love in all its many forms.” ~ Jacqueline Woodson Kwame Alexander is a poet, educator, and the NYT bestselling author of 28 ELIZABETH ACEVEDO is a NYT best- selling books. -

Urban Renewal and Postwar African American Poetry By

“If The House Is Not Yet Finished”: Urban Renewal and Postwar African American Poetry By Nilofar Gardezi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Lyn Hejinian, Chair Professor Eric Falci Professor Steven Lee Professor Waldo E. Martin Spring 2014 Abstract “If The House Is Not Yet Finished”: Urban Renewal and Postwar African American Poetry by Nilofar Gardezi Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Lyn Hejinian, Chair In my dissertation, I investigate the epic writings of Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Robert Hayden to tell the stories of black working class life and culture in postwar New York City, Chicago, and Detroit. I suggest that these writers’ modernist epics offer a counter-poetics to the “clean” modernism of urban renewal and, implicitly, lay bare the racial exclusionism foundational to not only urban renewal’s specific policies of segregation and displacement but also to its aesthetic claims to architectural avant-gardism and newness. This was a time of urban renewal-slum clearance programs that displaced and disrupted black communities—more specifically, a time when race, modernism, and geography all collided in urban renewal—and I argue that we can see both urban renewal and the poetic responses to it in terms of aesthetic modernism. In my first chapter, “Alternative Geographies of Community in Langston Hughes’s Montage of a Dream Deferred,” I claim that Hughes’s poem about the struggle for home and belonging in postwar Harlem invokes the importance of black self-determination and action through the democratic movements of bebop jazz and montage. -

Dr. Brian Gazaille

English 360: African American Writers Time, Memory, and Identity: Black Women Writers Instructor: Dr. Brian Gazaille (he/him/his) CRN: 31990 Office: PLC 206 Term: Spring 2019 Office Hours: MW 11:00-12:30, and by appointment Location: 107 ESL Phone: 541-346-5935 Time: MWF 10:00-10:50 Email: [email protected] (please give 48 hours for a response!) Course Description This class investigates how black women writers of the twentieth century have taken up the themes of time, memory, and identity. The writers we will explore—Frances E. W. Harper, Zora Neale Hurston, Gwendolyn Brooks, Audre Lorde, Ntzoake Shange, and Lucille Clifton, among others—conceived of literature as remembering. Poems and stories were not just artworks but places in which to recover silenced voices and reflect on the intractable legacies of patriarchy and racism. As Shange so succinctly puts it in her first novel, Sassafrass, Cypress, & Indigo, literature can be made to represent the “the slaves who were ourselves.” Using the short fiction, poetry, and critical work of the writers noted above, we will examine how black women writers adapted literary forms to wrestle with past and present forms of race- and gender-based oppression. This course counts toward UO’s Multicultural Requirement (Identity, Pluralism, and Tolerance). It also counts for two upper- division categories in English Major II: (1) Literature, 1789-Present, and (2) Race, Ethnicity, and Empire. For students in Major I, the class counts for (1) Literature, 1789-Present or (2) Folklore, Women’s Literatures, -

An Exhibition of American Printers' and Special Presses Devices

An Exhibition of American Printers’ and Special Presses Devices by Bronwyn Hannon, Hofstra University Axinn Library Special Collections The printers’ and special presses devices in this exhibition reflect certain times in the history of printing when concern for the integrity of book arts in the machine age is most acute. These presses devices can be seen as graphic stamps or markers indicating to the reader of a book that its types, layout, papers, illustrations and bindings have aspired to a higher level of excellence. The printers’ and presses devices featured here are among others in the collections held in Hofstra University Library Special Collections. Printers’ and Presses Devices ‐ A Definition Printers’ and special presses devices are small graphic logos, which operate in the same way as hallmarks in silver production, or china marks in porcelain production, or the signature marks of painters on their canvasses. Devices are usually found in the “colophon” at the end of printed books before 1500, and thereafter more frequently on the title‐page, which displayed other bibliographic details originally placed in the colophon. Colophons (from the Greek kolophon meaning “summit”) are essentially notes at the end of the book, often embellished with a printer’s device, and variously detailing title, author, printer, place of printing, date, edition and materials used. The words “device” and “mark” are used synonymously. American Printers’ and Presses Devices The prolific revival of the special presses movement in America followed closely from exemplar presses in Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century England. Often the design of printers’ and presses devices recalled eminent printers of the past. -

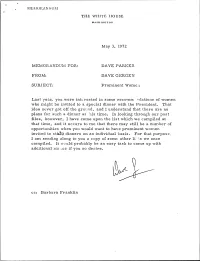

Dave Gergen to Dave Parker Re

MEf\IOR/\NIHJM THE WHITE HOUSE WASIIINGTON May 3, 1972 MEMORANDUM FOR: DAVE PARKER FROM: DAVE GERGEN SUBJECT: Prominent Wome~l Last year, you were int( rested in some recomrrj "c1ations of women who might be invited to a special dinner with the President. That idea never got off the ground, and I understand that there are no plans for such a dinner at :lis time. In looking through our past files, however, I have come upon the list which we compiled at that time, and it occurs to me that there Inay still be a number of opportunities when you would want to have prominent wom.en invited to st~~ dinners on an individual basis. For that purpose: I am sending along to you a copy of some other li i~S we once compiled. It would probably be an easy task to come up with additional nm, ~cs if you so desire. cc: Barbara Franklin r-------------------------------------------------------------- Acaflemic Hanna Arendt - Politic'al Scientist/Historian Ar iel Durant - Histor ian Gertrude Leighton - Due to pub lish a sem.ina 1 work on psychiatry and law, Bryn Mawr Katherine McBride - Retired Bryn Mawr President Business Buff Chandler - Business executive and arts patron Sylvia Porter - Syndicated financial colun1.nist Entertainment Mar ian And ",r son l Jacqueline I.. upre - British cellist Joan Gan? Cooney - President, Children1s Television Workshop; Ex(,cutive Producer of Sesaxne St., recently awarded honorary degre' fron'l Oberlin Agnes DeMille - Dance Ella Fitzgerald Margot Fonteyn - Ballerina Martha Graham. - Dance Melissa Hayden - Ballerina Helen Hayes Katherine Hepburn Jv1ahilia Jackson Mary Martin 11ary Tyler Moore Leontyne Price Martha Raye B(~verley Sills - Has appeared at "\V1-I G overnmcnt /Politics ,'.