Flood Risk Management Planning Resources for Washington DC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The District of Columbia Water Quality Assessment

THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT 2008 INTEGRATED REPORT TO THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY AND U.S. CONGRESS PURSUANT TO SECTIONS 305(b) AND 303(d) CLEAN WATER ACT (P.L. 97-117) District Department of the Environment Natural Resources Administration Water Quality Division Government of the District of Columbia Adrian M. Fenty, Mayor PREFACE PREFACE The Water Quality Division of the District of Columbia's District Department of the Environment, Natural Resources Administration, prepared this report to satisfy the listing requirements of §303(d) and the reporting requirements of §305(b) of the federal Clean Water Act (P.L. 97-117). This report provides water quality information on the District of Columbia’s surface and ground waters that were assessed during 2008 and updates the water quality information required by law. Various programs in the Natural Resources Administration contributed to this report including the Fisheries and Wildlife Division and the Watershed Protection Division. Questions or comments regarding this report or requests for copies should be forwarded to the address below. The District of Columbia Government District Department of the Environment Natural Resources Administration Water Quality Division 51 N St., NE Washington, D.C. 20002-3323 Attention: N. Shulterbrandt ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................................... ii TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................iii LIST OF TABLES........................................................... -

The District of Columbia Water Quality Assessment

THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT 2012 INTEGRATED REPORT TO THE US ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY AND CONGRESS PURSUANT TO SECTIONS 305(b) AND 303(d) CLEAN WATER ACT (P.L. 97-117) District Department of the Environment Natural Resources Administration Water Quality Division i PREFACE The Water Quality Division of the District of Columbia's District Department of the Environment, Natural Resources Administration, prepared this report to satisfy the listing requirements of §303(d) and the reporting requirements of §305(b) of the federal Clean Water Act (P.L. 97-117). The report provides water quality information on the District of Columbia’s surface and ground waters that were assessed during 2010-2011 and updates the water quality information required by law. Various programs in the Natural Resources Administration contributed to this report including the Fisheries and Wildlife Division, the Stormwater Management Division, and the Watershed Protection Division. The Lead and Healthy Housing Division, Environmental Protection Administration also contributed to this report. Questions or comments regarding this report should be forwarded to the address below. The District of Columbia Government District Department of the Environment Natural Resources Administration Water Quality Division 1200 First Street, NE 5th Floor Washington, D.C. 20002 Attention: N. Shulterbrandt ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... -

Federal Register/Vol. 79, No. 139/Monday, July 21

Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 139 / Monday, July 21, 2014 / Rules and Regulations 42197 connection with the acquisition or experimental or laboratory sense. Because When these regulations are enforced, production of depreciable property to be $50,000 of Z’s costs to construct the new test certain restrictions are placed on marine used in the taxpayer’s trade or business bed was incurred for research and traffic in specified areas. This are limited to amounts expended for experimentation, the costs qualify as research rulemaking project promotes efficiency or experimental expenditures under section research or experimentation within the 174. Paragraph (b)(2) of this section applies by eliminating the need to produce a meaning of section 174 and paragraph to $50,000 of Z’s costs for the test bed separate rule for each individual (a) of this section. because they are expenditures for research or recurring event, and serves to provide (5) Examples. The following examples experimentation that result in depreciable notice of the known recurring events illustrate the application of paragraph property to be used in the taxpayer’s trade or requiring a special local regulation or (b) of this section. business. Z’s remaining $4,950,000 of costs is safety zone throughout the year. not allowable under section 174 because Example 1. Amounts paid to others for DATES: This rule is effective August 20, these costs were not incurred for research or research or experimentation resulting in 2014. experimentation. depreciable property. X is a tool ADDRESSES: Documents mentioned in manufacturer. X has developed a new tool * * * * * this preamble are part of docket [USCG– design, and orders a specially-built machine (d) Effective/applicability date. -

The District of Columbia Water Quality Assessment

THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT 2006 INTEGRATED REPORT TO THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY AND U.S. CONGRESS PURSUANT TO SECTIONS 305(b) AND 303(d) CLEAN WATER ACT (P.L. 97-117) Department of Health Environmental Health Administration Bureau of Environmental Quality Water Quality Division Government of the District of Columbia Anthony A. Williams, Mayor PREFACE PREFACE The Water Quality Division of the District of Columbia's Department of Health, Environmental Health Administration, prepared this report to satisfy the listing requirements of §303(d) and the reporting requirements of §305(b) of the federal Clean Water Act (P.L. 97-117). This report provides water quality information on the District of Columbia’s surface and ground waters that were assessed during 2006 and updates the water quality information required by law. Various programs in the Bureau of Environmental Quality contributed to this report including the Watershed Protection Division and the Fisheries and Wildlife Division. Questions or comments regarding this report or requests for copies should be forwarded to the address below. The District of Columbia Government Department of Health Environmental Health Administration Bureau of Environmental Quality Water Quality Division 51 N St., NE Washington, D.C. 20002-3323 Attention: N. Shulterbrandt ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................................... ii TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................iii ACRONYMS .................................................................ix -

Potomac Park

46 MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN EDAW Enhance the Waterfront Experience POTOMAC PARK Potomac Park can be reimagined as a unique Washington destination: a prestigious location extending from the National Mall; a setting of extraordinary beauty and sweeping waterfront vistas; an opportunity for active uses and peaceful solitude; a resource with extensive acreage for multiple uses; and a shoreline that showcases environmental stewardship. Located at the edge of a dense urban center, Potomac Park should be an easily accessible place that provides opportunities for water-oriented recreation, commemoration, and celebration in a setting that preserves the scenic landscape. The park offers great potential to relieve pressure on the historic and fragile open space of the National Mall, a vulnerable resource that is increasingly overburdened with demands for large public gatherings, active sport fields, everyday recreation, and new memorials. Potomac Park and its shoreline should offer a range of activities for the enjoyment of all. Some areas should accommodate festivals, concerts, and competitive recreational activities, while other areas should be quiet and pastoral to support picnics under a tree, paddling on the river, and other leisure pastimes. The park should be connected with the region and with local neighborhoods. MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN 47 ENHANCE THE WATERFRONT EXPERIENCE POTOMAC PARK Context Potomac Park is a relatively recent addition to Ohio Drive parallels the walkway, provides vehicular Washington. In the early years of the city it was an access, and is used by bicyclists, runners, and skaters. area of tidal marshes. As upstream forests were cut The northern portion of the island includes 25 acres and agricultural activity increased, the Potomac occupied by the National Park Service’s regional River deposited greater amounts of silt around the headquarters, a park maintenance yard, offices for the developing city. -

Foundations for Memorials and Monuments on the National Mall

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine International Conference on Case Histories in (2008) - Sixth International Conference on Case Geotechnical Engineering Histories in Geotechnical Engineering 14 Aug 2008, 7:00 pm - 8:30 pm Foundations for Memorials and Monuments on the National Mall Douglas W. Christie Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers, New York, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge Part of the Geotechnical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Christie, Douglas W., "Foundations for Memorials and Monuments on the National Mall" (2008). International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering. 4. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge/6icchge/session08/4 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOUNDATIONS FOR MEMORIALS AND MONUMENTS ON THE NATIONAL MALL Douglas W. Christie, P.E. Associate Mueser Rutledge Consulting Engineers New York, New York 10122 ABSTRACT As the western end of the National Mall in Washington, DC was made by filling in portions of the Potomac River, memorials and monuments have required deep foundations. The site history including stream channels, canals, and materials used in filling various areas has had a large impact on the development of the Mall. -

A Flow-Simulation Model of the Tidal Potomac River

A Flow-Simulation Model of the Tidal Potomac River A Water-Quality Study of the Tidal Potomac River and Estuary United States Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 2234-D Chapter D A Flow-Simulation Model of the Tidal Potomac River By RAYMOND W. SCHAFFRANEK U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 2234 A WATER-QUALITY STUDY OF THE TIDAL POTOMAC RIVER AND ESTUARY DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1987 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Schaffranek, Raymond W. A flow-simulation model of the tidal Potomac River. (A water-quality study of the tidal Potomac River and Estuary) (U.S. Geological Survey water-supply paper; 2234) Bibliography; p. 24. Supt. of Docs, no.: I. 19.13:2234-0 1. Streamflow Potomac River Data processing. 2. Streamflow Potomac River Mathematical models. I. Title. II. Series. III. Series: U.S. Geological Survey water-supply paper; 2234. GB1207.S33 1987 551.48'3'09752 85-600354 Any use of trade names and trademarks in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. FOREWORD a rational and well-documented general approach for the study of tidal rivers and estuaries. This interdisciplinary effort emphasized studies of the Tidal rivers and estuaries are very important features transport of the major nutrient species and of suspended of the Coastal Zone because of their immense biological sediment. -

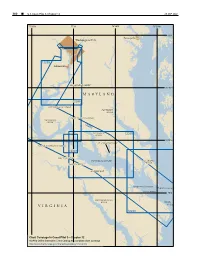

M a R Y L a N D V I R G I N

300 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 26 SEP 2021 77°20'W 77°W 76°40'W 76°20'W 39°N Annapolis Washington D.C. 12289 Alexandria PISCATAWAY CREEK 38°40'N MARYLAND 12288 MATTAWOMAN CREEK PATUXENT RIVER PORT TOBACCO RIVER NANJEMOY CREEK 12285 WICOMICO 12286 RIVER 38°20'N ST. CLEMENTS BAY UPPER MACHODOC CREEK 12287 MATTOX CREEK POTOMAC RIVER ST. MARYS RIVER POPES CREEK NOMINI BAY YEOCOMICO RIVER Point Lookout COAN RIVER 38°N RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER Smith VIRGINIA Point 12233 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 12 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 ¢ 301 Chesapeake Bay, Potomac River (1) This chapter describes the Potomac River and the above the mouth; thence the controlling depth through numerous tributaries that empty into it; included are the dredged cuts is about 18 feet to Hains Point. The Coan, St. Marys, Yeocomico, Wicomico and Anacostia channels are maintained at or near project depths. For Rivers. Also described are the ports of Washington, DC, detailed channel information and minimum depths as and Alexandria and several smaller ports and landings on reported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), these waterways. use NOAA Electronic Navigational Charts. Surveys and (2) channel condition reports are available through a USACE COLREGS Demarcation Lines hydrographic survey website listed in Appendix A. (3) The lines established for Chesapeake Bay are (12) described in 33 CFR 80.510, chapter 2. Anchorages (13) Vessels bound up or down the river anchor anywhere (4) ENCs - US5VA22M, US5VA27M, US5MD41M, near the channel where the bottom is soft; vessels US5MD43M, US5MD44M, US4MD40M, US5MD40M sometimes anchor in Cornfield Harbor or St. -

Washington's Waterfront Study

WASHINGTON’S WATERFRONTS Phase 1 December 1999 The Georgetown Waterfront Anacostia Park’s West Bank Potomac River r Rive Anacostia The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Washington Navy Yard and Southeast Waterfront National Capital Planning Commission Southwest Waterfront Anacostia Park’s East Bank 801 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Suite 301 Bolling Anacostia Waterfront Washington, D.C. 20576 tel 202 482-7200 fax 202 482-7272 An Analysis of Issues and Opportunities Along the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers www.ncpc.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION.............................................2 A. Overview B. Study Origin C. Study Process D. Study Goals E. Study Area II. THE WATERFRONT.......................................4 A. Regional Context B. Area Description C. Existing Conditions D. Land Use E. Transportation F. Urban Image III. WATERFRONT ISSUES..............................12 A. Identification of Concerns B. Planning Issues C. Opportunities D. Development Guidelines E. Implementation Tools IV. THE WATERFRONT PLAN.........................16 Recommended Outline V. CONCLUSION.............................................17 VI. APPENDIX..................................................18 1 7. Develop a waterfront redevelopment zone in areas 2. Enhance public access to the river. I. INTRODUCTION where major new development is proposed and ensure that existing maritime uses are protected. 3. Protect the natural setting of the valued open spaces A. Overview along the rivers. 8. Establish public transportation where needed and This document was developed to study the waterfront as a resource encourage the development of adequate parking in 4. Identify opportunities for attracting additional river- that belongs to all of the people of the United States and to the resi- redeveloped areas. related activities that can aid in revitalizing the District's dents of the District of Columbia. -

REFLECTIONS Washington’S Southeast / Southwest Waterfront

REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Copyright © 2021 by Square 656 Owner, LLC Front cover image: Rendering of the Frederick Douglass Memorial ISBN: 978-0-578-82670-7 Bridge. The bridge connects the two shores of Designed by LaserCom Design, Berkeley CA the Anacostia River and is named after a former slave and human rights leader who became one of Washington’s most famous residents. District Department of Transportation vi FOREWORD REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Marjorie Lightman, PhD William Zeisel, PhD CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront QED Associates LLC Washington, DC CAMBRIA HOTEL n REFLECTIONS vii Then ... A gardener’s residence on the site of the Cambria Hotel. The flat-roofed frame house, 18 feet wide and costing $1,800 to construct more than a century ago, was home to Samuel Howison, a market gardener. The cornice at the top of the building now graces the Cambria Hotel’s lobby, and a fireplace mantle accents the rooftop bar. Peter Sefton Now ... The Cambria Hotel at 69 Q Street SW, a part of the Southeast/Southwest waterfront’s renaissance. Donohoe Welcome to the Cambria Hotel Located in an historic part of one of the world’s great cities. ashington is a star-studded town where money and influence glitter on a world stage of W24/7 news bites. Images of the White House, the Capitol, and the Mall are recognized around the world as synonymous with majesty and power. Washington, the nation’s capital, shapes our times and history. -

District of Coulmbia: the Likelihood of Shore Protection

The Likelihood of Shore Protection in the District of Columbia James G. Titus U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington D.C. September 2005 Draft The final version of this document can be cited as: J.G. Titus. 2010. “District of Columbia.” In James G. Titus and Daniel Hudgens (editors). The Likelihood of Shore Protection along the Atlantic Coast of the United States. Volume 1: Mid- Atlantic. Report to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, D.C. The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official opinion of the Environmental Protection Agency. The primary referring page for this report is http://risingsea.net/ERL/DC.html CHAPTER 7 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA : James G. Titus U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [ 664 THE L I K E L I H O O D O F S H O R E P R O T E C T I O N I N T H E D I S T R I C T O F C O L U M B I A] CONTENTS Introduction................................................................................................................................... 665 Background................................................................................................................................... 667 Response to Sea Level Rise ........................................................................................................ 671 Stakeholder Review...................................................................................................................... 679 A Note on Horizontal Scale......................................................................................................... -

The Color of Wealth in the Nation's Capital

INEQUALITY AND MOBIL ITY (just RESEARCH REPORT The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital A Joint Publication of the Urban Institute, Duke University, The New School, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development Kilolo Kijakazi Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins Mark Paul Anne E. Price URBAN INSTITUTE THE NEW SCHOOL DUKE UNIVERSITY INSIGHT CENTER FOR COMMUNITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Darrick Hamilton William A. Darity Jr. THE NEW SCHOOL DUKE UNIVERSITY November 2016 American Gothic, Washington, DC, 1942. Photograph by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright the Gordon Parks Foundation. ABOUT THE URBAN INSTITUTE The nonprofit Urban Institute is dedicated to elevating the debate on social and economic policy. For nearly five decades, Urban scholars have conducted research and offered evidence-based solutions that improve lives and strengthen communities across a rapidly urbanizing world. Their objective research helps expand opportunities for all, reduce hardship among the most vulnerable, and strengthen the effectiveness of the public sector. ABOUT THE SAMUEL DUB OIS COOK CENTER ON S OCIAL EQUITY AT DUKE UNIVERSITY The Duke Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity is a scholarly collaborative engaged in the study of the causes and consequences of inequality and in the assessment and redesign of remedies for inequality and its adverse effects. Concerned with the economic, political, social, and cultural dimensions of uneven and inequitable access to resources, opportunity and capabilities, Cook Center researchers take a cross-national comparative approach to the study of human difference and disparity. Ranging from the global to the local, Cook Center scholars not only address the overarching social problem of general inequality, but they also explore social problems associated with gender, race, ethnicity, and religious affiliation.