The Reasonable Doubt Rule and the Meaning of Innocence Scott E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Death Penalty Issues Michael Meltsner

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 74 Article 1 Issue 3 Fall Fall 1983 Current Death Penalty Issues Michael Meltsner Marvin E. Wolfgang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Michael Meltsner, Marvin E. Wolfgang, Current Death Penalty Issues, 74 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 659 (1983) This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/83/7403-659 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 74, No. 3 Copyright 0 1983 by Northwestern University School of Law Printedin US.A. INTRODUCTION In 1976, a divided United States Supreme Court upheld state capi- tal sentencing laws on the assumption that explicit sentencing guide- lines, separate sentencing hearings and automatic appellate review of all death sentences would remove the substantial risk of arbitrariness of previous capital punishment sentencing schemes.I Eight years later, the premises supporting the constitutionality of the new laws appear to have little practical currency. That a set of scholarly contributions from law- yers, criminologists, and other investigators would uncover flaws in the operation of the death-case legal system is not surprising; earlier re- search into the operation of the discretionary death penalty systems raised significant doubts about the reliability, fairness, and necessity of capital punishment and contributed to the Court's landmark 1972 deci- sion in Furman v. -

Consequences of Failing to Admit Guilt at Parole Hearings Daniel S

MEDWED_TRANSMITTED.DOC2 2/26/2008 1:51 PM The Innocent Prisoner’s Dilemma: Consequences of Failing to Admit Guilt at Parole Hearings Daniel S. Medwed∗ INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 493 I. THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF PAROLE ................................................ 497 A. HISTORICAL ORIGINS AND PURPOSES OF PAROLE ................................ 497 B. PAROLE RELEASE DECISION-MAKING: CONTEMPORARY STANDARDS AND POLICIES .................................................................................... 504 II. THE EFFECT OF PAROLE RELEASE DECISION-MAKING NORMS ON THE INNOCENT ............................................................................................... 513 A. PAROLE: AN INNOCENCE OPTION OF LAST RESORT ............................. 518 B. PRESSURE ON INNOCENT INMATES TO “ADMIT” GUILT ........................ 523 III. ADMISSIONS OF GUILT AND THE PAROLE RELEASE DECISION RECONSIDERED ....................................................................................... 529 A. THE DANGER OF ASSUMING THE LITIGATION PROCESS ACCURATELY FILTERS THE GUILTY FROM THE INNOCENT ......................................... 530 B. POTHOLES ON THE PATH TO REDEMPTION THROUGH THE PAROLE PROCESS ........................................................................................... 532 IV. SUGGESTIONS FOR REFORM .................................................................... 541 A. LIMITATIONS ON THE SUBSEQUENT USE OF STATEMENTS FROM PAROLE HEARINGS ........................................................................... -

The Presumption of Innocence As a Counterfactual Principle Ferry De Jong & Leonie Van Lent*

This article is published in a peer-reviewed section of the Utrecht Law Review The Presumption of Innocence as a Counterfactual Principle Ferry de Jong & Leonie van Lent* 1. Introduction The presumption of innocence is widely, if not universally, recognized as one of the central principles of criminal justice, which is evidenced by its position in all international and regional human rights treaties as a standard of fair proceedings.1 Notwithstanding this seemingly firm normative position, there are strong indications that the presumption of innocence is in jeopardy on a practical as well as on a normative level. The presumption of innocence has always been much discussed, but in the last decade the topic has generated a particularly significant extent of academic work, both at the national and at the international level.2 The purport of the literature on this topic is twofold: many authors discuss developments in law and in the practice of criminal justice that curtail suspects’ rights and freedoms, and criticize these developments as being violations of the presumption of innocence. Several other authors search for the principle’s normative meaning and implications, some of whom take a critical stance on narrow interpretations of the principle, whereas others assert – by sometimes totally differing arguments – that the presumption of innocence has and should have a more limited normative meaning and scope than is generally attributed to it. An important argument for narrowing down the principle’s meaning or scope of application is the risk involved in a broad conception and a consequently broad field of applicability, viz. that its specific normative value becomes overshadowed and that concrete protection is hampered instead of furthered.3 The ever-increasing international interest in the topic is reflected also in the regulatory interest in the topic on the EU level. -

Compensation Chart by State

Updated 5/21/18 NQ COMPENSATION STATUTES: A NATIONAL OVERVIEW STATE STATUTE WHEN ELIGIBILITY STANDARD WHO TIME LIMITS MAXIMUM AWARDS OTHER FUTURE CONTRIBUTORY PASSED OF PROOF DECIDES FOR FILING AWARDS CIVIL PROVISIONS LITIGATION AL Ala.Code 1975 § 29-2- 2001 Conviction vacated Not specified State Division of 2 years after Minimum of $50,000 for Not specified Not specified A new felony 150, et seq. or reversed and the Risk Management exoneration or each year of incarceration, conviction will end a charges dismissed and the dismissal Committee on claimant’s right to on grounds Committee on Compensation for compensation consistent with Compensation Wrongful Incarceration can innocence for Wrongful recommend discretionary Incarceration amount in addition to base, but legislature must appropriate any funds CA Cal Penal Code §§ Amended 2000; Pardon for Not specified California Victim 2 years after $140 per day of The Department Not specified Requires the board to 4900 to 4906; § 2006; 2009; innocence or being Compensation judgment of incarceration of Corrections deny a claim if the 2013; 2015; “innocent”; and Government acquittal or and Rehabilitation board finds by a 2017 declaration of Claims Board discharge given, shall assist a preponderance of the factual innocence makes a or after pardon person who is evidence that a claimant recommendation granted, after exonerated as to a pled guilty with the to the legislature release from conviction for specific intent to imprisonment, which he or she is protect another from from release serving a state prosecution for the from custody prison sentence at underlying conviction the time of for which the claimant exoneration with is seeking transitional compensation. -

Cops Or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dimitri Epstein, Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epstein: Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute App COPS OR ROBBERS? HOW GEORGIA'S DEFENSE OF HABITATION STATUTE APPLIES TO NONO- KNOCK RAIDS BY POLICE Dimitri Epstein*Epstein * INTRODUCTION Late in the fall of 2006, the city of Atlanta exploded in outrage when Kathryn Johnston, a ninety-two-year old woman, died in a shoot-out with a police narcotics team.team.' 1 The police used a "no"no- knock" search warrant to break into Johnston's home unannounced.22 Unfortunately for everyone involved, Ms. Johnston kept an old revolver for self defense-not a bad strategy in a neighborhood with a thriving drug trade and where another elderly woman was recently raped.33 Probably thinking she was being robbed, Johnston managed to fire once before the police overwhelmed her with a "volley of thirty-nine" shots, five or six of which proved fatal.fata1.44 The raid and its aftermath appalled the nation, especially when a federal investigation exposed the lies and corruption leading to the incident. -

Life Imprisonment and Conditions of Serving the Sentence in the South Caucasus Countries

Life Imprisonment and Conditions of Serving the Sentence in the South Caucasus Countries Project “Global Action to Abolish the Death Penalty” DDH/2006/119763 2009 2 The list of content The list of content ..........................................................................................................3 Foreword ........................................................................................................................5 The summary of the project ..........................................................................................7 A R M E N I A .............................................................................................................. 13 General Information ................................................................................................... 14 Methodology............................................................................................................... 14 The conditions of imprisonment for life sentenced prisoners .................................... 16 Local legislation and international standards ............................................................. 26 Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 33 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 36 A Z E R B A I J A N ........................................................................................................ 39 General Information .................................................................................................. -

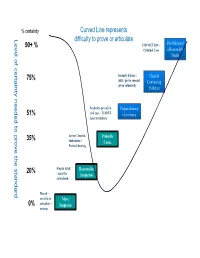

Level of Certainty Needed to Prove the Standard

% certainty Curved Line represents Level of certainty needed to prove the standard needed toprove of certainty Level difficulty to prove or articulate 90+ % CONVICTION – Proof Beyond Criminal Case a Reasonable Doubt 75% Insanity defense / Clear & alibi / prove consent Convincing given voluntarily Evidence Needed to prevail in Preponderance 51% civil case – LIABLE of evidence Asset Forfeiture 35% Arrest / Search / Probable Indictment / Cause Pretrial hearing 20% Stop & Frisk Reasonable – must be Suspicion articulated Hunch – not able to Mere 0% articulate / Suspicion no stop Mere Suspicion – This term is used by the courts to refer to a hunch or intuition. We all experience this in everyday life but it is NOT enough “legally” to act on. It does not mean than an officer cannot observe the activity or person further without making contact. Mere suspicion cannot be articulated using any reasonably accepted facts or experiences. An officer may always make a consensual contact with a citizen without any justification. The officer will however have not justification to stop or hold a person under this situation. One might say something like, “There is just something about him that I don’t trust”. “I can’t quit put my finger on what it is about her.” “He looks out of place.” Reasonable Suspicion – Stop, Frisk for Weapons, *(New) Search of vehicle incident to arrest under Arizona V. Gant. The landmark case for reasonable suspicion is Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) This level of proof is the justification police officers use to stop a person under suspicious circumstances (e.g. a person peaking in a car window at 2:00am). -

Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders

Introductory Handbook on The Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover photo: © Rafael Olivares, Dirección General de Centros Penales de El Salvador. UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2018 © United Nations, December 2018. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface The first version of the Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders, published in 2012, was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Canada, and Yvon Dandurand, crimi- nologist at the University of the Fraser Valley, Canada. The initial draft of the first version of the Handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert group meeting held in Vienna on 16 and 17 November 2011.Valuable suggestions and contributions were made by the following experts at that meeting: Charles Robert Allen, Ibrahim Hasan Almarooqi, Sultan Mohamed Alniyadi, Tomris Atabay, Karin Bruckmüller, Elias Carranza, Elinor Wanyama Chemonges, Kimmett Edgar, Aida Escobar, Angela Evans, José Filho, Isabel Hight, Andrea King-Wessels, Rita Susana Maxera, Marina Menezes, Hugo Morales, Omar Nashabe, Michael Platzer, Roberto Santana, Guy Schmit, Victoria Sergeyeva, Zhang Xiaohua and Zhao Linna. -

Commitment After Acquittal on Grounds of Insanity M

Maryland Law Review Volume 22 | Issue 4 Article 3 Commitment After Acquittal On Grounds of Insanity M. Albert Figinski Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation M. A. Figinski, Commitment After Acquittal On Grounds of Insanity, 22 Md. L. Rev. 293 (1962) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol22/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1962] COMMITMENT AFTER ACQUITTAL 293 COMMITMENT AFTER ACQUITIAL ON GROUJND'S OF INS'ANITYt By M. ALBERT FIGINsKI* I. THE PROCEDURES OF CRIMINAL COMMITMENT GENERALLY "Jurors, in common with people in general, are aware of the meanings of verdicts of guilty and not guilty. It is common knowledge that a verdict of not guilty means that the prisoner goes free and that a verdict of guilty means that he is subject to such punishment as the court may impose. But a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity has no such commonly understood meaning."' This lack of knowledge can logically result from two factors. One, the verdict is a rare one in our society, given the state of extreme dementation required by the "right and wrong test" to acquit. Second, unlike the verdicts of guilty and not guilty which have the same meaning and effect throughout Anglo-American jurisprudence, the meaning and effect of a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity are dependent upon statutes and vary among the states. -

Indeterminate Sentence Release on Parole and Pardon Edward Lindsey

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 8 | Issue 4 Article 3 1918 Indeterminate Sentence Release on Parole and Pardon Edward Lindsey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lindsey, Indeterminate Sentence Release on Parole and Pardon, 8 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 491 (May 1917 to March 1918) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. INDETERIMlNATE SENTENCE, RELEASE ON PAROLE AN) PARDON (REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE OF THE INSTITUTE.') EDWARD LINDSEY, 2 Chairman. The only new state to adopt the indeterminate sentence the past year is North Carolina. In that state, by act of March 7, 1917, entitled, "An act to regulate the treatment, handling and work of prisoners," it is provided that all persons convicted of crime in any of the courts of the state whose sentence shall be for five years or more shall be -sent to the State Prison and the Board of Directors of the State Prison "is herewith authorized and directed to establish such rules and regulations as may be necessary for developing a system for paroling prisoners." The provisions for indeterminate .sentences are as follows: "The various judges of the Superior Court -

Justice in Jeopardy

RWANDA JUSTICE IN JEOPARDY THE FIRST INSTANCE TRIAL OF VICTOIRE INGABIRE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2013 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2013 Index: AFR 47/001/2013 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Victoire Ingabire at the High Court of Kigali, Rwanda, November 2011. © STEVE TERRILL/AFP/Getty Images amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Acronyms.................................................................................................................5 -

Case Law Update, March 2019

Sex Offender Registration and Notification in the United States Current Case Law and Issues March 2019 Sex Offender Registration and Notification in the United States: Current Case Law and Issues March 2019 Contents I. Overview of U.S. Sex Offender Registration ......................................................................... 1 Registration is a Local Activity ................................................................................................. 1 Federal Minimum Standards ................................................................................................... 1 National Sex Offender Public Website ..................................................................................... 1 Federal Law Enforcement Databases ...................................................................................... 2 Federal Corrections ................................................................................................................. 3 Federal Law Enforcement and Investigations......................................................................... 3 II. Who Is Required to Register? .......................................................................................... 3 ‘Conviction’ .............................................................................................................................. 3 ‘Sex Offenders’ ......................................................................................................................... 4 ‘Catch-All’ Provisions .............................................................................................................