Innocent Characters in the Novels of Dickens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oliver Twist; Or, the Parish Boy's Progress (1838) Is Charles Dickens's Second Novel

Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress (1838) is Charles Dickens's second novel. It was first published as a book by Richard Bentley in 1838. It tells the story of an orphan boy and his adventures among London's slums. Oliver is captured by, and forced to work among, pickpockets and thieves until redeemed by a gentleman who has taken an interest in him. Characters include Fagin, Nancy, Bill Sykes, and the Artful Dodger. The book David Copperfield is a novel by Charles is one of the earliest examples of the social novel. It draws the Dickens. Like his other novels, it first came out as a series in a reader's attention to contemporary evils such as child labour, the magazine under the title The Personal History, Adventures, recruitment of children as criminals, and the presence of street Experience and Observation of David Copperfield the Younger of children. Blunderstone Rookery (which he never meant to publish on any The novel may have been inspired by the story of Robert Blincoe, account)[1] an orphan whose account of hardships as a child labourer in a The story is told in the first person. Some of the greatest Dickens cotton mill was widely read in the 1830s. It is likely that Dickens's characters appear in the novel, such as the evil clerk Uriah Heep. own early youth as a child labourer contributed to the story's Other villains in David's life are his brutal stepfather, Edward development. The book influenced American writer Horatio Alger, Murdstone, and Mr. -

David Copperfield: Victorian Hero

David Copperfield: Victorian Hero by James A. Hamby A Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the College of Graduate Studies of Middle Tennessee State University Murfreesboro, Tennessee August 2012 UMI Number: 3528680 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. OiSi«Wior» Ftattlisttlfl UMI 3528680 Published by ProQuest LLC 2012. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Submitted by James A. Hamby in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, specializing in English. Accepted on behalf of the Faculty of the College of Graduate Studies by the dissertation committee: Date: Quaul 3-1.9J310. Rebecca King, Ph.D. ^ Chairperson Date:0ruu^ IX .2.612^ Elvira Casal^Ph.D. N * Second Reader f ./1 >dimmie E. Cain, Ph.D. Af / / / y # Third Reader / diPUt Date:J Tom Strawman, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English (lULa.lh Qtt^bate: 7 SI '! X Michael D.)'. Xllen, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Graduate Studies © 2012 James A. Hamby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For my family. -

Five Novels Oliver Twist a Christmas Carol David Copperfield Tale of Two Cities Great Expectations Charles Dickens

FIVE NOVELS OLIVER TWIST A CHRISTMAS CAROL DAVID COPPERFIELD TALE OF TWO CITIES GREAT EXPECTATIONS CHARLES DICKENS PDF-29FNOTACCDCTOTCGECD0 | Page: 117 File Size 5,182 KB | 24 Feb, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction Brief Description Main Topic Technical Note Appendix Glossary PDF File: Five Novels Oliver Twist A Christmas Carol David Copperfield Tale Of Two Cities Great 1/2 Expectations Charles Dickens - PDF-29FNOTACCDCTOTCGECD0 Five Novels Oliver Twist A Christmas Carol David Copperfield Tale Of Two Cities Great Expectations Charles Dickens e-Book Name : Five Novels Oliver Twist A Christmas Carol David Copperfield Tale Of Two Cities Great Expectations Charles Dickens - Read Five Novels Oliver Twist A Christmas Carol David Copperfield Tale Of Two Cities Great Expectations Charles Dickens PDF on your Android, iPhone, iPad or PC directly, the following PDF file is submitted in 24 Feb, 2021, Ebook ID PDF-29FNOTACCDCTOTCGECD0. Download full version PDF for Five Novels Oliver Twist A Christmas Carol David Copperfield Tale Of Two Cities Great Expectations Charles Dickens using the link below: Download: FIVE NOVELS OLIVER TWIST A CHRISTMAS CAROL DAVID COPPERFIELD TALE OF TWO CITIES GREAT EXPECTATIONS CHARLES DICKENS PDF The writers of Five Novels Oliver Twist A Christmas Carol David Copperfield Tale Of Two Cities Great Expectations Charles Dickens have made all reasonable attempts to offer latest and precise information and facts for the readers of this publication. The creators will not be held accountable for any unintentional flaws or omissions that may be found. PDF File: Five Novels Oliver Twist A Christmas Carol David Copperfield Tale Of Two Cities Great 2/2 Expectations Charles Dickens - PDF-29FNOTACCDCTOTCGECD0. -

Troubled Masculinity at Midlife: a Study of Dickens's Hard Times

235 Troubled Masculinity at Midlife: A Study of Dickens’s Hard Times HATADA Mio Hard Timesで提示される “Fact”と“Fancy”の2つの対照的な世界、あるいは価値観は、一見 すると相反するもののように思われるが、この小説は両者の対立よりもむしろ、両者がいかに 密接な関係を持っているかを暗示しているように思われる。そして、主要な登場人物は複雑に 絡まり合ったこれら2つの世界に、それぞれのやり方で関わりを持ち、反応を示す。興味深い ことに、2つの絡み合う世界は、主要な人物(その多くは中年の男性である)の抱えている問 題とも密接な関係を持っている。本稿ではHard Timesにおける2つの世界を、作品中で直接姿 を現すことのないSissy の父親の存在を手がかりに、中年期の男性が経験するmasculinityの危 機、という観点から再考している。 キーワード:aging, masculinity, gender Introduction It is well known that F. R. Leavis included Hard Times in his work The Great Tradition, calling it “a completely serious work of art” (Leavis 258) with the “subtlety of achieved art” (Leavis 279). Much earlier, John Ruskin estimated the novel as “the greatest” of Dickens’s novels, and asserted that it “should be studied with close and earnest care by persons interested in social questions” (34). Many other critics make much of the aspect of Hard Times as a critique of the contemporary society, and it has often been treated with other industrial novels such as Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (1855). Humphry House, for instance, points out that Dickens was “thinking much more about social problems,” and that “Hard Times is one of Dickens’s most thought-about books.” He goes on to assert that “in the ’fi fties, his novels begin to show a greater complication of plot than before” because “ he was intending to use them as a vehicle of more concentrated sociological argument” (House 205). David Lodge, too, affi rms, “Hard Times manifests its identity as a polemical work, a critique of mid-Victorian industrial society dominated by materialism, acquisitiveness and ruthlessly competitive capitalist economics,” which are “represented... by the Utilitarians” (Lodge 69‒70). -

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

Ch apter 1 In reading my story, you’ll decide whether I’m the hero of my own life or someone else is. I was born at Blunderstone in Suffolk. My father, David, had died six months before, at the age of thirty-nine. His aunt, Betsey Trotwood, was the head of the family. Aunt Betsey had been married to a younger man who had been very handsome and was said to have abused her. They had separated. Aunt Betsey had taken back her birth name, bought a seaside house in Dover, established herself there as a single woman with one servant, and lived in near-seclusion. It was believed that her husband had gone to India and died there ten years later. My father had been a favorite of Aunt Betsey until his marriage, which had deeply offended her. She never had met my mother, Clara. However, because my mother had been only nineteen when she married my father, then thirty- eight, Aunt Betsey had taken offense and referred to my mother as a “wax doll.” My father and Aunt Betsey had never seen each other again. The day before I was born was a bright, windy March day. My mother was in poor health and in low spirits. Dressed in mourning because of my father’s 1 2 CHARLES DICKENS recent death, she sat in the parlor by the fi re shortly before sunset. When she lifted her sad eyes to the window opposite her, she saw an unfamiliar lady coming up the walk. The lady was Aunt Betsey. -

Charles Dickens' Great Expectations

Overbey 1 Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations: The Failed Redeemers and Fate of the Orphan A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English By Rebekah Grace Overbey 15 April 2013 Overbey 2 Liberty University College of General Studies Master of Arts in English Dr. Emily Heady_______________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. William Gribbin_____________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Professor Christopher Nelson______________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Overbey 3 Table of Contents Introduction: Great Expectations: Pip and the End of the Romantic Child…………………….4 Chapter 1: Maternal Figures or Monsters: Mrs. Joe and Molly………………………………..18 Chapter 2: Fallen Godparents and the Inverted Fairy Tale…………………………………….34 Chapter 3: Jaggers and the State: The Inability to Redeem……………………………………50 Chapter 4: Joe, Pip, and the Pattern of Forgiveness……………………………………………65 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………….82 Overbey 4 Introduction Great Expectations: Pip and the End of the Romantic Child 1860: Twenty-three years after the reign of Queen Victoria began, one year after Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, and the year that Charles Dickens first began publishing Great Expectations. With the country reeling from the upheaval of the Industrial Revolution and theological crisis stemming from the theory of evolution, Great Expectations was born into a world of rapid social, political, and economic change. Dickens’ own world was in flux as the serial publication began: in the two years preceding the novel, Dickens had divorced his wife, sold his home, and burned years’ worth of correspondence with friends and family. In an environment of dizzying change, it should come as no surprise that Great Expectations deviates from Dickens’ typical orphan tale. -

The Treatment of Children in the Novels of Charles

THE TREATMENT OF CHILDREN IN THE NOVELS OF CHARLES DICKENS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY CLEOPATRA JONES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 1948 ? C? TABLE OF CONTENTS % Pag® PREFACE ii CHAPTER I. REASONS FOR DICKENS' INTEREST IN CHILDREN ....... 1 II. TYPES OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 10 III. THE FUNCTION OF CHILDREN IN DICKENS' NOVELS 20 IV. DICKENS' ART IN HIS TREATMENT OF CHILDREN 33 SUMMARY 46 BIBLIOGRAPHY 48 PREFACE The status of children in society has not always been high. With the exception of a few English novels, notably those of Fielding, child¬ ren did not play a major role in fiction until Dickens' time. Until the emergence of the Industrial Revolution an unusual emphasis had not been placed on the status of children, and the emphasis that followed was largely a result of the insecure and often lamentable position of child¬ ren in the new machine age. Since Dickens wrote his novels during this period of the nineteenth century and was a pioneer in the employment of children in fiction, these facts alone make a study of his treatment of children an important one. While a great deal has been written on the life and works of Charles Dickens, as far as the writer knows, no intensive study has been made of the treatment of children in his novels. All attempts have been limited to chapters, or more accurately, to generalized statements in relation to his life and works. -

Dombey and Son: Charles Dickens and the Business of Family Monthly Course at the Rosenbach Syllabus

Dombey and Son: Charles Dickens and the Business of Family Monthly Course at the Rosenbach Syllabus Location: The Rosenbach 2008-2010 Delancey Place, Philadelphia, PA 19103 Time: Tuesdays, 6:00-7:45pm (for dates, see schedule below) Instructor: Christine Woody, Assistant Professor, Widener University [email protected] / (347) 243-1680 Contacts: Edward Pettit, Sunstein Manager of Public Programs [email protected] / (215) 732-1600 ext. 135 Texts: If you are in the market for a copy of our book, please consider seeking out the edition listed below. This will facilitate our discussions as pagination will be the same. However, please do feel free to use edition you may already own of our novel. Dickens, Charles. Dombey and Son. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0140435467. Goals & Approaches: Over our four monthly class sessions, we will dive deep into one of Dickens’ less-read masterpieces. Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son: Wholesale, Retail and for Exportation, serialized between October 1846 and April 1848, deals with the fate of the business and family (inextricably intertwined) of one Paul Dombey. The novel provides new insight into the connections between many of Dickens’ well-known social concerns—class conflict, cruelty to children, unhappy marriages, and the pressures of Victorian capitalism. As we wend our way through the novel’s rich tapestry of competing plotlines and compelling social portraiture, we will have the opportunity not only to consider how it reconfigures the themes and questions of more familiar novels (David Copperfield, Oliver Twist, and their ilk) but also to examine what Dombey and Son reveals about the questions we still ask ourselves today about the competing values of work and family and the process of reconciling them. -

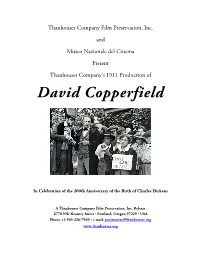

David Copperfield

Thanhouser Company Film Preservation, Inc. and Museo Nazionale del Cinema Present Thanhouser Company’s 1911 Production of David Copperfield In Celebration of the 200th Anniversary of the Birth of Charles Dickens A Thanhouser Company Film Preservation, Inc. Release 8770 NW Kearney Street • Portland, Oregon 97229 • USA Phone +1-503-226-7960 • e-mail: [email protected] www.thanhouser.org Press Kit: David Copperfield (1911) Credits Produced by ................................... Edwin Thanhouser Directed by .................................... George O. Nichols Starring .......................................... Flora Foster (David Copperfield as a young boy) Ed Genung (David Copperfield as a young man) Marie Eline (Little Em’ly as a young girl) Florence LaBadie (Em’ly as a young woman) Mignon Anderson (Dora) Marguerite Snow (Agnes) James Cruze (Steerforth) William Russell (Ham) New and Original Music by ........... Dr. Philip Carli (Rochester, New York) Commentary by ............................. Professor Joss Marsh (Indiana University/Kent-MOMI) 1911 USA Release .......................... Thanhouser Company (New Rochelle, New York) 1911 European Distribution .......... Western Import Company, Ltd. (London, England) 1959 Preservation ........................... Museo Nazionale del Cinema (Torino, Italy) 2012 Restoration ............................ Museo Nazionale del Cinema (Torino, Italy) 2012 DVD Release ........................ Thanhouser Company Film Preservation, Inc. (Portland, Oregon) Black and White, 1.33 : 1 aspect ratio, -

David Copperfield

LEVEL 3 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme David Copperfield Charles Dickens when the latter leaves London, owing to his debts, EASYSTARTS David decides to go in search of his only relative, Miss Trotwood, whom he finds in Dover. Davis is sent to school again and becomes a great friend of Agnes Wickfield’s, at whose house he stays when he’s not at LEVEL 2 school. Chapters 7–8: After finishing school David goes to LEVEL 3 Yarmouth to visit Peggotty, who has married Mr Barkis. There, he meets Steerforth who seems upset that Emily, Mr Peggotty’s niece, is marrying her friend Ham. At LEVEL 4 Mr Spenlow’s, with whom David is going to study law, he falls in love with Dora, his daughter. Chapters 9–10: David arrives at Yarmouth after About the author LEVEL 5 Mr Barkis’s death. There he hears that Emily has run off Charles Dickens, the most popular writer of the Victorian with Steerforth. Mr Peggotty is devastated and starts age, was born near Portsmouth, England, in 1812 and searching for her. he died in Kent in 1870. When his father was thrown Back in London David proposes to Dora and is accepted. LEVEL 6 into debtors’ prison, young Charles was taken out of school and forced to work in a shoe-polish factory, which Chapters 11–12: When Miss Trotwood informs David may help explain the presence of so many abandoned that she has lost all her money, all his plans collapse. He and victimised children in his novels. As a young man starts learning shorthand to find a good job in order to he worked as a reporter before starting his career as be able to marry Dora. -

Our Mutual Friend"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 "My Lords and Gentlemen and Honourable Boards": Narrative and Social Criticism in "Our Mutual Friend" Gregory Eric Huteson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Huteson, Gregory Eric, ""My Lords and Gentlemen and Honourable Boards": Narrative and Social Criticism in "Our Mutual Friend"" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625603. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-6xbb-7s05 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "MY LORDS AND GENTLEMEN AND HONOURABLE BOARDS" Narrative Audience and Social Criticism in Our Mutual Friend A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Gregory Eric Huteson 1990 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ■y Eric HutesonGfego, Approved, August 1990 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer would like to confess a debt of gratitude to Professor Deborah Morse, who directed the thesis, for her astute criticism and her patience. He would also like to express his appreciation to Professor Mary Ann Kelly for her comments and criticism and to Professor Terry Meyers for his careful readings and his advice and encouragement. -

The Storm Scene in David Copperfield ANTHONY KEARNEY

The Storm Scene in David Copperfield ANTHONY KEARNEY HAPTER 55 of David Copperfield ("Tempest") is by general account one of the best-remembered passages in the whole of Dickens. Dickens drew on his deepest imaginative strengths in creating the scene and the result, as Forster said, "is a description that may compare with the most impressive in the language."1 For Ruskin, who thought Turner's painting of the steamer in distress merely "a good study of wild weather," there was nothing in either painting or literature to compare with Dickens' storm.2 Later readers, too, have responded with similar enthusiasm to the brilliant description of the furious wind and sea and to the high drama of Ham's vain attempt to save Steer- forth from drowning. Yet several questions remain to be asked about this passage. Dickens' novels contain a good many storm scenes of one kind or another, why is this scene so much more memorable than any of the others? Is it simply a question of more powerfully sustained writing, or of something more? On the face of it, like any other writer producing a storm at a climactic moment, Dickens ran the risk of lapsing into mere contrivance: why is it that the reader has no real sense of things being forced or exploited in this chapter? Why does this storm have a poetic relevance and value in relation to larger happenings in the novel where other fictional storms do not? In the present article I should like to look more closely at these questions. Dickens, of course, was well-practised in utilising the dramatic effects of storms in his writings by the time he came to David Copperfield.