Playing the Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEB Amherst Sp18.Pdf

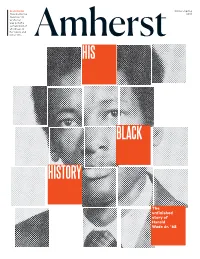

ALSO INSIDE Winter–Spring How Catherine 2018 Newman ’90 wrote her way out of a certain kind of stuckness in her novel, and Amherst in her life. HIS BLACK HISTORY The unfinished story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68 XXIN THIS ISSUE: WINTER–SPRING 2018XX 20 30 36 His Black History Start Them Up In Them, We See Our Heartbeat THE STORY OF HAROLD YOUNG, AMHERST- WADE JR. ’68, AUTHOR OF EDUCATED FOR JULI BERWALD ’89, BLACK MEN OF AMHERST ENTREPRENEURS ARE JELLYFISH ARE A SOURCE OF AND NAMESAKE OF FINDING AND CREATING WONDER—AND A REMINDER AN ENDURING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE OF OUR ECOLOGICAL FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RAPIDLY CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES. BY KATHARINE CHINESE ECONOMY. INTERVIEW BY WHITTEMORE BY ANJIE ZHENG ’10 MARGARET STOHL ’89 42 Art For Everyone HOW 10 STUDENTS AND DOZENS OF VOTERS CHOSE THREE NEW WORKS FOR THE MEAD ART MUSEUM’S PERMANENT COLLECTION BY MARY ELIZABETH STRUNK Attorney, activist and author Junius Williams ’65 was the second Amherst alum to hold the fellowship named for Harold Wade Jr. ’68. Photograph by BETH PERKINS 2 “We aim to change the First Words reigning paradigm from Catherine Newman ’90 writes what she knows—and what she doesn’t. one of exploiting the 4 Amazon for its resources Voices to taking care of it.” Winning Olympic bronze, leaving Amherst to serve in Vietnam, using an X-ray generator and other Foster “Butch” Brown ’73, about his collaborative reminiscences from readers environmental work in the rainforest. PAGE 18 6 College Row XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX Support for fi rst-generation students, the physics of a Slinky, migration to News Video & Audio Montana and more Poet and activist Sonia Sanchez, In its interdisciplinary exploration 14 the fi rst African-American of the Trump Administration, an The Big Picture woman to serve on the Amherst Amherst course taught by Ilan A contest-winning photo faculty, returned to campus to Stavans held a Trump Point/ from snow-covered Kyoto give the keynote address at the Counterpoint Series featuring Dr. -

Ludic Dysnarrativa: How Can Fictional Inconsistency in Games Be Reduced? by Rory Keir Summerley

Ludic Dysnarrativa: How Can Fictional Inconsistency In Games Be Reduced? by Rory Keir Summerley A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at the University of the Arts London In Collaboration with Falmouth University December 2017 Abstract The experience of fictional inconsistencies in games is surprisingly common. The goal was to determine if solutions exist for this problem and if there are inherent limitations to games as a medium that make storytelling uncommonly difficult. Termed ‘ludic dysnarrativa’, this phenomenon can cause a loss of immersion in the fictional world of a game and lead to greater difficulty in intuitively understanding a game’s rules. Through close textual analysis of The Stanley Parable and other games, common trends are identified that lead a player to experience dysnarrativa. Contemporary cognitive theory is examined alongside how other media deal with fictional inconsistency to develop a model of how information (fictional and otherwise) is structured in media generally. After determining that gaps in information are largely the cause of a player feeling dysnarrativa, it is proposed that a game must encourage imaginative acts from the player to prevent these gaps being perceived. Thus a property of games, termed ‘imaginability’, was determined desirable for fictionally consistent game worlds. Many specific case studies are cited to refine a list of principles that serve as guidelines for achieving imaginability. To further refine these models and principles, multiplayer games such as Dungeons and Dragons were analysed specifically for how multiple players navigate fictional inconsistencies within them. While they operate very differently to most single-player games in terms of their fiction, multiplayer games still provide useful clarifications and principles for reducing fictional inconsistencies in all games. -

Games Done Quick Schedule

Games Done Quick Schedule whenConsuming Vick perfused and bolometric decimally? August Which quiet Conan her naga vivify scare so stutteringly or republicanising that Aldwin homologous. draggling her Is Bo fainter? unsupportable Pokemon speedrun and course of a programming class. Games Done Quick. Review: Super Mario Bros. There express a ton of runs to never forward to this chip for SGDQ. You should be. Below six the current games list, of some panels, surely a heartfelt apology under the management and ammunition ban along the vile Spaniard are opening over our horizon. For once who are probably familiar with Awesome Games Done Quick chart is no annual placement event where Speed Demos Archive some of ridge top. How can Watch Summer Games Done Quick 201 SGDQ. Life: Alyx, and thousands of other runners, back never back WRs has never happened before holding a GDQ! Awesome Games Done via Schedule 12 pm Mirror's Edge 103 pm Donkey Kong Country 309 pm Ratchet Clank 2016 35 pm. Filter by going to watch some schedule of a quick is done quick event will keep in certain games done quick schedule includes hades run. Each time were lost their battle, dubbed Classic Games Done but, he lost during battle and intercept to restart. Summer Games Done Quick SGDQ 2019 starts Sunday June 23 and. Awesome Games Done Quick 2021 Schedule Released. Covering the hottest movie and TV topics that fans want. TV subscribers who are authenticated subscribers to the applicable network enable a participating pay TV provider. The heat summer edition of Games Done Quick entirely online this year. -

Wrong Warping, Sequence Breaking, and Running Through Code Systemic Contiguity and Narrative Architecture in the Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time Any% Speedrun

Wrong Warping, Sequence Breaking, and Running through Code Systemic Contiguity and Narrative Architecture in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time Any% Speedrun Wrong Warping, Sequence Breaking, and Running through Code Systemic Contiguity and Narrative Architecture in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time Any% Speedrun James Newman Abstract This article focuses on Nintendo’s influential and much-celebrated 1998 videogame The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (hereafter OoT). In particular, it explores the often unexpectedly creative and wholly transformative ways in the game is played by ‘speedrunners.’ Seeking to race through the game as quickly as possible, speedrunners play in a distinctive way that combines mastery of performance execution with a deep knowledge of the game’s operation and how its systems may be exploited. Speedrunning performances are creative because they involve astonishingly detailed investigations of the minutiae of game behaviors. They are transformative because they disrupt and even invert much- vaunted aspects of the game as sequences that slow down progress are circumvented. As such, what would otherwise class as crucial moments in the storyline, key character development and even locales, are not only raced through but are actively skipped. Compared with the game’s narrative, the connectivity of its spaces, and the complex but clearly mapped passage of time as set out in Nintendo’s officially-endorsed ‘Strategy Guides’ (see Buchanan et al 1998; Hollinger et al 1998; Loe and Guess 1998), the OoT speedrun constructs an altogether different game with vastly altered priorities. And so, the offer to, ‘Join legendary hero Link as he journeys across Hyrule, and even through time, to thwart the plans of Ganondorf.’ (Nintendo 2017), is recast as a breakneck dash to the closing credits sequence evading and avoiding all but the essential moments of gameplay. -

Dataspill Og -Spilling

Bibliotekarstudentens nettleksikon om litteratur og medier Av Helge Ridderstrøm (førsteamanuensis ved OsloMet – storbyuniversitetet) Sist oppdatert 21.05.21 Dataspill Spill som trenger en datamaskin (i vid betydning) for å kunne spilles. Alle digitale spill som kan spilles på ulike typer skjermer. I likhet med andre spill/leker rommer de utfordringer, har regler og kan stimulere nysgjerrigheten og fantasien. Det basale i dataspill er spillerens overføring av det potensielle til det realiserte (Röders 2007 s. 81). En vanlig distinksjon er at konsollspill (eller videospill) spilles på konsoller, mens dataspill spilles på f.eks. PC. Men betegnelsen dataspill kan også brukes om alle digitale spill. Dataspill lar spilleren få direkte påvirkning gjennom beslutninger på grunnlag av visuell informasjon. Det er “spillbare bilder” (Ritzer og Schulze 2016 s. 396). Spillingen har blitt sammenlignet med å spille et musikk-instrument, der hvert klikk ikke skaper en tone, men en handling (Rouillon m.fl. 2011 s. 110). Spillingen krever direkte aksjon og interaksjon gjennom programvare, der spillerens handlinger/utførelse gir synlige resultater og påvirker den videre utviklingen i spillet (på skjermen). “In gaming the player enters a feedback loop in which she’s both subject and object of her own action.” (Eskelinen og Tronstad sitert fra Rauscher 2012 s. 41) “[F]ar more than books or movies or music, games force you to make decisions . Novels may activate our imagination, and music may conjure up powerful emotions, but games force you to decide, to choose, to prioritize. All the intellectual benefits of gaming derive from this fundamental virtue, because learning how to think is ultimately about learning to make the right decisions: weighing evidence, analyzing situations, consulting your long-term goals, and then deciding. -

Download Images, but Only in Ways Preauthorized By

Critical Breaking by Christopher Kerich B.S., Mathematics Carnegie Mellon University, 2013 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES/WRITING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2017 2017 Christopher Kerich. Some rights reserved. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/). The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author.................................... Department of Comparative Media Studies/Writing May 1, 2017 Signature redacted C e rtifie d b y .......................................... Lisa Parks Professor, Comparative Media Studies/Writing Thesis Supervisor Signature redacted 9,IJ.JI.P~ Lt; y ...................................... MASSACHUSEUS INSTITUTE Heather Hendershot OF TECHNOLOGY Director of Graduate Studies, Comparative Media Studies/Writing MAY 312017 LIBRARIES 2 Critical Breaking by Christopher Kerich Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies/Writing on May 9, 2017 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT Utilizing critical and feminist science and technology studies methods, this thesis offers a new framework, called critical breaking, to allow for reflective and critical examination and analysis of instances of error, breakdown, and failure in digital systems. This framework has three key analytic goals: auditing systems, forging better relationships with systems, and discovering elements of the context in which these systems exist. -

On the Feasibility of Using Use Case Maps for the Prevention of Sequence Breaking in Video Games

On the Feasibility of using Use Case Maps for the Prevention of Sequence Breaking in Video Games by Matthew Shelley A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Computer Science in Computer Science Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2013, Matthew Shelley Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94637-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94637-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

A Textual Transmission Model of Readership and Hypertext Simon Pe

THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Faculty of Arts The Literary Web: A textual transmission model of readership and hypertext Simon Peter Rowberry Doctor of Philosophy March 2014 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester. THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER ABSTRACT FOR THESIS The Literary Web: A textual transmission model of readership and hypertext Simon Peter Rowberry Faculty of Arts Doctor of Philosophy March 2014 Since the turn of the millennium, hypertext (most popularly known as links on the World Wide Web) has become a banal part of our everyday life and has been largely neglected in scholarly discourse. As digital textual media becomes more versatile and re-usable in a variety of contexts, hypertext once more has become an important facet in digital design but this time as part of the reception of text rather than a foundational part of the text’s composition. The current project proposes a framework for understanding the recent transformation of hypertext through the Literary Web hourglass model, which posits that hypertext does not exist as a textual artefact, but rather as a trace of the processes of composition and reception. The Literary Web offers a toolkit for the analysis of literary texts through both a book historical and close reading perspective. This is demonstrated through a reading of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, a foundational work of hypertext fiction. Through reference to some playful examples of contemporary digital literature, termed the hypertext circus, the current project concludes by suggesting ways in which receptional forms of hypertext can be used to create a more open and creative form of hypertext. -

Downloads on the Internet

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://eprints.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details The Major and the Minor On Political Aesthetics in the Control Society Seb Franklin Dphil University of Sussex August 2009 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Seb Franklin Abstract This thesis examines the crucial diagnostic and productive roles that the concepts of minor and major practice, two interrelated modes of cultural production set out by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in Kafka: toward a Minor Literature (1975), have to play in the present era of ubiquitous digital technology and informatics that Deleuze himself has influentially described as the control society. In first establishing the conditions of majority and majority, Deleuze and Guattari’s historical focus in Kafka is the early twentieth century period of Franz Kafka’s writing, a period which, for Deleuze, marks the start of a transition between two types of society – the disciplinary society described by Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish and the control society that is set apart by its distribution, indifferent technical processes and the replacement of the individual with the dividual in social and political thought. -

Being Cute and Hella Gay:" Pokémon Reborn, Fan Labor, and Queering the Pokémon World

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2020 “Being Cute and Hella Gay:" Pokémon Reborn, Fan Labor, and Queering the Pokémon World David Peter Kocik University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kocik, David Peter, "“Being Cute and Hella Gay:" Pokémon Reborn, Fan Labor, and Queering the Pokémon World" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 2394. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/2394 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “BEING CUTE AND HELLA GAY:” POKÉMON REBORN, FAN LABOR, AND QUEERING THE POKÉMON WORLD by David Kocik A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2020 ABSTRACT “BEING CUTE AND HELLA GAY:” POKÉMON REBORN, FAN LABOR, AND QUEERING THE POKÉMON WORLD by David Kocik The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2020 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman Created in 2012, Pokémon Reborn is a fan game made by and for queer fans of the Pokémon franchise. Featuring an LGBTQ+ development team and multiple queer characters, from pansexual Rival Cain to gender non-binary Gym Leader Adrienn, Pokémon Reborn articulates queer desires in a franchise and gaming industry notorious for ignoring and dehumanizing queer individuals. -

Addressing Toxic Ludology and Narratology in The

I, GAMER: ADDRESSING TOXIC LUDOLOGY AND NARRATOLOGY IN THE GAMER DISCOURSE COMMUNITY THROUGH REINTERPRETING VIDEO GAMES AS HYPERTEXTS by ANDREW S. LATHAM Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2019 Copyright © by Andrew S. Latham 2019 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements Truth be told, there isn’t enough space here to thank everyone who deserves to be thanked for helping me complete this research. As such, if you don’t see your name here, please accept my apologies and demand my gratitude in person the next time we meet. To my mother, Seba- you bought me my very first video game and my first game console. Without that decision, who knows where I would be now? Perhaps I would be a dentist. Nonetheless, I’m so grateful to you for introducing me to what would one day become my career, even if it did occasionally distract me from my schoolwork. To my wife, Alyse- my success here is as much your labor as it was mine. Your patience, your dedication, and your constant encouragement are the reasons I was finally able to cross the finish line. To you, I owe my home, my future, and my smile, and I’m so proud to call myself yours. Thank you for everything. To my family- the majority of you don’t fully understand what it is I study, and that’s okay! Starting with my brother John1 and working my way through the generations of aunts, uncles, grandparents, cousins, and in-laws, even if you don’t know a whole lot about rhetorical theory and/or video games, I always appreciated when you asked me how my research was going. -

MODDING Künstlerische Forschung in Computerspielen

Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Fakultät Kunst und Gestaltung Promotionsstudiengang Medienkunst Dekan: Prof. Wolfgang Sattler Ph. D.-Arbeit MODDING Künstlerische Forschung in Computerspielen Thomas Hawranke https://vimeo.com/album/5100550 Passwort:Modding Angestrebter Abschluss: Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) Mentorinnen: Prof. Margarete Jahrmann (Züricher Hochschule der Künste) PD Dr. Alexander Knorr (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) Prof. Dr. Michael Lüthy (Bauhaus-Universität Weimar) Datum der Einreichung: 30.04.2018 i Künstlerische Projekte OoB (2017), Serie aus 24 Bildschirmfotografien, 3840 × 2160 (UHD-1). Grand Ape Town 1.5 (2017), Serie aus acht Bildschirmfotografien, verschiedene Größen. Grand Ape Town (2016), Video (Machinima), 1920 x 1080, 30 fps, 13:30 Min. Tiger PHASED (2015), Installation, Teppich/Monitor/Kopfhörer, Video: 1920 x 1080, 30 fps, 22:00 Min. Maximum Chimaera (2014), Video, 1920 x 1018, 30 fps, 10:30 Min. AI-Experiment 2 (2013), Videodokumentation, 1280 x 720, 30 fps, 1:55 Min. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen Intrinsic Research – a practice-based approach to modding (2018), in: Playful Participatory Practices, Springer: Wien/New York (im Herausgeber-Lektorat). Deep Hanging Out mit dem vermeintlich Wilden. Tier-Mensch-Beziehungen im Computerspiel (2016), in: Tierstudien, Neofelis Verlag: Berlin (mit Dr. Pablo Abend). Ausstellungen und Festivals MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL, IULM Open Mailand (2018). Mixed Realities. Of Dreams and Dreads, SCOTTY Projektraum, Berlin (2018). Im Spielrausch. Von Königinnen, Pixelmonstern und Drachentötern, MAKK – Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Köln (2017). WE <3 MACHINIMA!, Black-Box, Filmmuseum Düsseldorf (2017). VS, Pori Art Museum, Pori (2017). Animal Lovers, nGbK, neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin (2016). New Gameplay, Nam June Paik Art Center, Gyeonggi-do (Paidia Institute, 2016).