Punk and Theories of Cultural Hybridity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demo-2014.Pdf

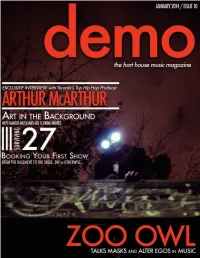

Demo Magazine 2014.indd 1 1/1/2014 5:17 PM FOXMOULDER (SEAN DECORY) ANTONY & THE JOHNSONS (MEDIA PHOTO) 16 26 JANUARY 2014 / ISSUE 10 Editor-in-Chief Elena Gritzan Emily Scherzinger 18 Layout Editor Marko Cindric Contributing Adam Bernhardt Writers Marko Cindric LETTER FROM THE EDITOR ELENA GRITZAN Elena Gritzan In a way, I came to U of T to become involved in Demo. I found a copy in the Arbor Room when I was on Kurt Grunsky Al Janusis campus for a tour and ended up spending the rest of the afternoon visiting the local record stores featured in Sian Last its pages. Demo taught me that Toronto has an exciting music scene which, along with the fact that I’ve always Aviva Lev-Aviv loved big cities, was a huge incentive to make this city my home. Erik Masson Kalina Nedelcheva I found the magazine’s table during Frosh Week’s Clubs Day and signed up to write. I’ve always loved music Emily Scherzinger INSIDE Ayla Shiblaq and writing, so it seemed like the perfect fun thing to do between classes, but I never could have guessed how THINGS TO BRING TO A CONCERT 4 Maria Sokulsky-Dolnycky much of an impact Demo would have on my life. Since becoming an editor in my third year, Demo has Michael Vettese taught me a lot about writing, editing, and leadership, but the real lesson I gained from the experience, and the FOUR PLACES TO SEE A SHOW FOR $5 5 Melissa Vincent other writing experiences it gave me the confidence to pursue, is what I want to do with my life. -

Middle Class Music in Suburban Nowhere Land: Emo and the Performance of Masculinity

MIDDLE CLASS MUSIC IN SUBURBAN NOWHERE LAND: EMO AND THE PERFORMANCE OF MASCULINITY Matthew J. Aslaksen A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Becca Cragin Angela Nelson ii Abstract Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Emo is an emotional form that attracts a great deal of ridicule from much of the punk and indie music communities. Emo is short for “emotional punk” or “emotional hardcore,” but because of the amount of evolution it has undergone it has become a very difficult genre to define. This genre is well known for its almost whiny sound and its preoccupation with relationship problems and emotional instability. As a result, it is seen by many within the more underground music community as an inauthentic emotionally indulgent form of music. Emo has also very recently become a form that has gained widespread mainstream media appeal with bands such as Dashboard Confessional, Taking Back Sunday, and My Chemical Romance. It is generally consumed by a younger teenaged to early college audience, and it is largely performed by suburban middle class artists. Overall, I have argued that emo represents challenge to conventional norms of hegemonic middle-class masculinity, a challenge which has come about as a result of feelings of discontent with the emotional repression of this masculinity. In this work I have performed multiple interviews that include both performers and audience members who participate in this type of music. The questions that I ask the subjects of my ethnographic research focus on the meaning of this particular performance to both the audience and performers. -

The Punk Effect: Art School Bands, Artist Collectives, and the Makings of an Alternative Culture in Downtown Toronto 1976-1978

The Punk Effect: Art School Bands, Artist Collectives, and the Makings of an Alternative Culture in Downtown Toronto 1976-1978 By Jakub Marshall A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree Master of Arts (MA) in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2019 Jakub Marshall 2 Abstract This thesis aims to examine the intersections of music, art and politics in late 1970s Toronto, particularly among the artists and musicians of the nascent Queen Street West scene. My research has two intertwined goals. First, to investigate the effect that the nearby Ontario College of Art had on this scene and how local art students’ formal training may have impacted their music. Secondly, the symbiotic connection between established artists and the local punk scene will be explored, through a discussion of how artist collectives General Idea and the Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication appropriated punk aesthetics and enlisted punk groups in order to further their own artistic ends. To address these questions, pertinent theoretical models are applied, including; Birmingham School subcultural theory, theories of the avant-garde, and sociological high culture/mass culture debates. Acknowledgments I would like to thank first, William Echard, my thesis supervisor for the duration of this project, and the Faculty of Music at Carleton University for supporting this work. Special thanks go to Philip Monk and Ian Mackay for their eager willingness to be interviewed, and for their illuminating suggestions of new research avenues. I would like to thank my parents for their unconditional support of me and my strange interests and investments. -

The Creative Independent

September 30, 2016 - Ian MacKaye founded Dischord Records in 1980 with the other three members of the band he played bass for in high school, the Teen Idles. Their original intention was to distribute a 7" from their recently defunct band. Later that year, MacKaye and Teen Idles drummer, Jeff Nelson formed the hardcore band, Minor Threat. After that group broke up in 1983, MacKaye went on to be a member of the short-lived band, Embrace, in 1985, and then in 1987 he formed Fugazi with Joe Lally, Brendan Canty, and Guy Picciotto. Fugazi toured the world and released records for the next 15 years before announcing an “indefinite hiatus.” Since 2003, MacKaye has played with his wife, drummer Amy Farina, in the Evens, and continues working on new music. He is still running Dischord Records after 36 years of documenting music coming from the DC punk underground. As told to Brandon Stosuy, 6399 words. Tags: Music, Independence, Focus, Inspiration. Ian MacKaye and Brandon Stosuy on independence, creativity, and The Creative Independent NOTE: This is a section of a longer conversation between Ian MacKaye and Brandon Stosuy that took place at Kickstarter’s Theater at 58 Kent Street in Greenpoint on August 24, 2016. It was not an interview. It was a conversation. It was also a free public event. After MacKaye and Stosuy talked, the audience asked questions. The tone throughout was lighthearted, the audience often breaking into laughter. Ian: [looks out at audience] Thanks for coming out for the conversation. We were just discussing what we’re going to talk about, and Brandon said he would like to talk about independence but I said, “Why don’t we start with this?” And this is how we’d like to start: Can you please explain to me, what is The Creative Independent? Brandon: Sure, I’ll give context. -

Politics As Unusual: Washington, D.C

Abstract Title of Dissertation: POLITICS AS UNUSUAL: WASHINGTON, D.C. HARDCORE PUNK 1979-1983 AND THE POLITICS OF SOUND Shayna L Maskell, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Nancy Struna, Chair, Department of American Studies During the creative and influential years between 1979 and 1983, hardcore punk was not only born — a mutated sonic stepchild of rock n’ roll, British and American punk — but also evolved into a uncompromising and resounding paradigm of and for DC youth. Through the revelatory music of DC hardcore bands like Bad Brains, Teen Idles, Minor Threat, State of Alert, Government Issue and Faith a new formulation of sound, and a new articulation of youth, arose: one that was angry, loud, fast, and minimalistic. With a total of only ten albums between all five bands in a mere five years, DC hardcore cemented a small yet significant subculture and scene. This project considers two major components of this music: aesthetics and the social politics that stem from those aesthetics. By examining the way music communicates — facets like timbre, melody, rhythm, pitch, volume and dissonance — while simultaneously incorporating an analysis of hardcore’s social context — including the history of music’s cultural canons, as well as the specific socioeconomic, racial and gendered milieu in which music is generated, communicated and responded to —this dissertation attempts to understand how hardcore punk conveys messages of social and cultural politics, expressly representations of race, class and gender. In doing so, this project looks at how DC hardcore (re)contextualizes and (re)imagines the social and political meanings created by and from sound. -

The Raw Original DOA

Music Review: D.O.A. Smash The State: The Raw Original D.O.A. 197... http://blogcritics.org/archives/2007/09/22/110821.php Blogcritics is an online magazine, a community of writers and readers from around the globe. Publisher: Eric Olsen REVIEW Music Review: D.O.A. Smash The State: The Raw Original D.O.A. 1978-81 DVD Written by Richard Marcus Published September 22, 2007 It's pretty hard to believe that it's been a little more than 30 years since the Sex Pistols released Never Mind The Bollocks their first and last studio album. In spite of bands like the Ramones, The New York Dolls, and others playing a similar type of high energy rock and roll, it was the Pistols who garnered all the publicity and became the face of Punk Rock for the media and everybody else. England of the mid to late 1970s was in a horrible state with unemployment running rampant among the young. Facing the prospect of a life of poverty and a series of dead end jobs until death, is it any wonder that they were more then a little bit angry and very nihilistic? When Johnny Rotten was singing "no future" the majority of the audience related to the statement personally. If you went to see the Pistols live, you didn't expect to hear many of the lyrics, but the music was another story. It was loud, abrasive, aggressive, and best of all angry, which not only summed up how the audience felt but gave them the means to express it as well by pogoing with wild abandon. -

Is Toronto Burning? Is Toronto Burning? Is the Story of the Rise of the Downtown Toronto Art Scene in the Late 1970S

Is Toronto Burning? Is Toronto Is Toronto Burning? is the story of the rise of the downtown Toronto art scene in the late 1970s. If the mid-1970s was a formless period, and if there was no dominant art movement, out of what disintegrated elements did new formations arise? Liberated from the influence of New York and embedding themselves in the decaying and unregulated edges of downtowns, artists created new scenes for themselves. Such was the case in Toronto, one of the last—and lost—avant-gardes of the 1970s. In the midst of the economic and social crises of the 1970s, Toronto was pretty vacant—but out of these conditions its artists crafted something unique, sometimes taking the fiction of a scene for the subject of their art. It was not all posturing. Performative frivolity and political earnestness were at odds with each other, but in the end their mutual conviviality and contestation fashioned an original art scene. This was a moment when an underground art scene could emerge as its own subcultural form, with its own rites of belonging and forms of transgression. It was a moment of cross-cultural contamination as the alternative music scene found its locale in the art world. Mirroring the widespread destruction of buildings around them, punk’s demolition was instrumental in artists remaking themselves, transitioning from hippie sentimentality to new wave irony. Then the police came. As an art critic in Toronto from 1977 to 1984, Philip Monk was ideally placed to observe the origins of its downtown art scene. Subsequently, he was a curator at the Art Gallery of Ontario Philip Monk and the Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, and currently is Director of the Art Gallery of York University. -

Punk Rock from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Punk rock From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Punk rock is a rock music genre that developed Punk rock between 1974 and 1976 in the United States, the Stylistic Rock and roll • folk • rockabilly • United Kingdom, and Australia. Rooted in garage rock and other forms of what is now known as protopunk origins surf rock • garage rock • glam rock • music, punk rock bands eschewed perceived excesses pub rock • protopunk of mainstream 1970s rock. Punk bands created fast, Cultural Mid-1970s, United States, United hard-edged music, typically with short songs, stripped- origins Kingdom, and Australia down instrumentation, and often political, anti- establishment lyrics. Punk embraces a DIY ethic; many Typical Vocals • electric guitar • bass • bands self-produced recordings and distributed them instruments drums • through informal channels. occasional use of other instruments By late 1976, bands such as the Ramones, in New Mainstream Topped charts in UK during late York City, and the Sex Pistols and The Clash, in popularity 1970s. International commercial London, were recognized as the vanguard of a new success for pop punk and ska punk, musical movement. The following year saw punk rock mid-1990s–2000s. spreading around the world, and it became a major Derivative New Wave • post-punk • cultural phenomenon in the United Kingdom. For the forms gothic rock • alternative rock • most part, punk took root in local scenes that tended to reject association with the mainstream. An associated grunge • emo punk subculture emerged, expressing youthful rebellion Subgenres and characterized by distinctive styles of clothing and adornment and a variety of anti-authoritarian Anarcho-punk • art punk • Christian punk • ideologies. -

X-Mist Distro-Catalog – January 2011

X-MIST DISTRO-CATALOG – JANUARY 2011 X-MIST RECORDS Releases 2BAD „Long Way Down“ 5Song-CDep (pre-STEAKKNIFE)..........CD 2,00 BIG BOYS „Lullabies Help The Brain Grow/No Matter How Long“ DOUBLE-LP reissue of Texas Punk CLASSICS!!!...DoLP 8,90 CROWD OF ISOLATED „Memories & Scars“ full album..........CD 2,50 ENIAC “Oh?” 2nd album, CD-only with bonus-tracks!........CD 5,60 EX MODELS/SECONDS Split-EP with 2 songs by each band!!!..7" 2,50 EX MODELS „Chrome Panthers“ 3rd full album!!!............LP 5,60 FUCKUISMYNAME „Catelbow“ 4Song-EP........................7“ 2,50 HAMMERHEAD “Stay Where The Pepper Grows” re-issue LP/CD ea. 6,50 HELL NO “Superstar Chop” 3Song-EP from 1994..............7" 1,00 HELL NO “Adios Armageddon” 2nd full album.........LP/CD ea. 3,00 HOSTAGES OF AYATOLLAH “Anthoalogy” Double-LP, including DVD & mp3-Download-Coupon! 12,50 KURT “Schesaplana Plus” 2xLP set combining their classic first & second album!...DoLP 8,50 KURT “La Guard” 3rd LP, limited repress on white vinyl!..LP 5,60 KURT „RMXD“ 12“ including 2 new tracks & 4 remixes!!!...12“ 4,90 SECONDS “Y” LP (members of EX MODELS & YEAH YEAH YEAHS!).LP 5,60 TELEMARK “Viva Suicide” first full album!.........LP/CD ea. 5,60 TELEMARK “Informat” NEW full album!!!........LP(+DC)/CD ea. 6,90 TEN VOLT SHOCK "78 Hours" NEW album!......black vinyl LP+CD 7,90 "78 Hours" limited white vinyl edition....LP 7,50 Both versions packed in 3-color silkscreen-sleeves! TEN VOLT SHOCK “6 Null 3” 2nd full album!!!.......LP/CD ea.