Regional Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brazos Valley Coordinated Transportation Plan Update

2017 Brazos Valley Coordinated Transportation Plan Update Approved by Independent Stakeholder Committee, February 15, 2017 BRAZOS VALLEY COORDINATED TRANSPORTATION PLAN UPDATE Thank you This update of the 2017 Coordinated Transportation Plan was made possible by numerous stakeholders throughout the region. We would like to thank our staff and numerous stakeholders and active citizens for their participation in this plan. BVCOG Staff Navasota Cab & Courier Leon County Health Resource Michael Parks Rance Parham Center Travis Halm Donna Danford Clay Barnett Texas Veterans Commission Gloria McCarty Jeffrey English Troy Robie Monica Rainey Madison County Health Vietnam Veterans Association Resource Center Brazos Transit District Thomas Powell Towanda Webber Wendy Weedon Sarah Santoy Workforce Solutions – Jobs Calvert Senior Center Center & Childcare Bea Cephas Brazos Valley Center for Gaylen Lange Independent Living Robert Gonzales Washington County Healthy Jackie Pacha Living Association Andrew Morse Area Agency on Aging Toy Kurtz Troy Howell Ronnie Gipson Cyndy Belt Stephen Galvin City of Bryan Tracy Glass Lindsay Hackett Department of Assistive and Brazos Valley Area Agency on Rehabilitative Services Regional Citizens Aging Virginia Herrera Ann Boehm Ronnie Gipson Steven Galvin Texas A&M Health Science Center Bryan-College Station MPO Karla Blaine Daniel Rudge Debbie Muesse Brad McCaleb Elizabeth Gonzalez-Silva Bart Benthul Angela Alaniz Heart of Texas Regional Burleson County Health Advisory Council Resource Commission Gary Clouse Albert Ramirez Sherii Alexander Housing Voucher Program Karla Flanagan Grimes County Health Resource Center Workforce Solutions Brazos Betty Feldman Valley Lara Meece Patricia Buck Nancy Franek Shawna Rendon 1 BRAZOS VALLEY COORDINATED TRANSPORTATION PLAN UPDATE Contents Thank you ........................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................... -

Groundwater Conservation Districts * 1

Confirmed Groundwater Conservation Districts * 1. Bandera County River Authority & Groundwater District - 11/7/1989 2. Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer CD - 8/13/1987 DALLAM SHERMAN HANSFORD OCHILTREE LIPSCOMB 3. Bee GCD - 1/20/2001 60 4. Blanco-Pedernales GCD - 1/23/2001 5. Bluebonnet GCD - 11/5/2002 34 6. Brazoria County GCD - 11/8/2005 HARTLEY MOORE HUTCHINSON ROBERTS 7. Brazos Valley GCD - 11/5/2002 HEMPHILL 8. Brewster County GCD - 11/6/2001 9. Brush Country GCD - 11/3/2009 10. Calhoun County GCD - 11/4/2014 OLDHAM POTTER CARSON WHEELER 11. Central Texas GCD - 9/24/2005 63 GRAY Groundwater Conservation Districts 12. Clear Fork GCD - 11/5/2002 13. Clearwater UWCD - 8/21/1999 COLLINGSWORTH 14. Coastal Bend GCD - 11/6/2001 RANDALL 15. Coastal Plains GCD - 11/6/2001 DEAF SMITH ARMSTRONG DONLEY of 16. Coke County UWCD - 11/4/1986 55 17. Colorado County GCD - 11/6/2007 18. Comal Trinity GCD - 6/17/2015 Texas 19. Corpus Christi ASRCD - 6/17/2005 PARMER CASTRO SWISHER BRISCOE HALL CHILDRESS 20. Cow Creek GCD - 11/5/2002 21. Crockett County GCD - 1/26/1991 22. Culberson County GCD - 5/2/1998 HARDEMAN 23. Duval County GCD - 7/25/2009 HALE 24. Evergreen UWCD - 8/30/1965 BAILEY LAMB FLOYD MOTLEY WILBARGER 27 WICHITA FOARD 25. Fayette County GCD - 11/6/2001 36 COTTLE 26. Garza County UWCD - 11/5/1996 27. Gateway GCD - 5/3/2003 CLAY KNOX 74 MONTAGUE LAMAR RED RIVER CROSBY DICKENS BAYLOR COOKE 28. Glasscock GCD - 8/22/1981 COCHRAN HOCKLEY LUBBOCK KING ARCHER FANNIN 29. -

The Brazos Valley Groundwater Conservation District: a Case

THE BRAZOS VALLEY GROUNDWATER CONSERVATION DISTRICT: A CASE STUDY IN TEXAS GROUNDWATER CONSERVATION Katherine D. Teel, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Randolph B. Campbell, Major Professor Andrew Torget, Committee Member J. Todd Moye, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Teel, Katherine D. The Brazos Valley Groundwater Conservation District: A case study in Texas groundwater conservation. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 90 pp., 6 illustrations, bibliography, 110 titles. This thesis examines the history of groundwater management through the development of groundwater conservation districts in Texas. Political, economic, ideological, and scientific understandings of groundwater and its regulation varied across the state, as did the natural resource types and quantities, which created a diverse and complicated position for lawmakers and landowners. Groundwater was consistently interpreted as a private property right and case law protected unrestricted use for the majority of the twentieth-century even as groundwater resources crossed property and political boundaries, and water tables declined particularly during the second-half of the century. The case study of the Brazos Valley Groundwater Conservation District describes the complicated history of groundwater in Texas as the state attempted to balance natural resource legislation and private property rights and illuminate groundwater’s importance for the future. Copyright 2011 by Katherine D. Teel ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to personally thank my committee for leading me through the thesis process and degree. The entire committee was helpful and encouraging throughout, consistently challenged my academic abilities, and pushed me to develop as a historian. -

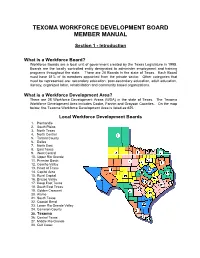

Texoma Workforce Development Board Member Manual

TEXOMA WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT BOARD MEMBER MANUAL Section 1 - Introduction What is a Workforce Board? Workforce Boards are a local unit of government created by the Texas Legislature in 1995. Boards are the locally controlled entity designated to administer employment and training programs throughout the state. There are 28 Boards in the state of Texas. Each Board must have 51% of its members appointed from the private sector. Other categories that must be represented are: secondary education, post-secondary education, adult education, literacy, organized labor, rehabilitation and community based organizations. What is a Workforce Development Area? There are 28 Workforce Development Areas (WDA) in the state of Texas. The Texoma Workforce Development Area includes Cooke, Fannin and Grayson Counties. On the map below, the Texoma Workforce Development Area is listed as #25. Local Workforce Development Boards 1. Panhandle 2. South Plains 3. North Texas 4. North Central 5. Tarrant County 6. Dallas 7. North East 8. East Texas 9. West Central 10. Upper Rio Grande 11. Permian Basin 12. Concho Valley 13. Heart of Texas 14. Capital Area 15. Rural Capital 16. Brazos Valley 17. Deep East Texas 18. South East Texas 19. Golden Crescent 20. Alamo 21. South Texas 22. Coastal Bend 23. Lower Rio Grande Valley 24. Cameron County 25. Texoma 26. Central Texas 27. Middle Rio Grande 28. Gulf Coast Who is a CEO? The CEOs are the Chief Elected Officials for each Board area. CEOs are defined in the legislation (HB 1863) that created Boards. For Texoma, the CEOs are the three county judges and the mayor of the largest city (Sherman). -

Soil Survey of Brazos County, Texas

United States In cooperation with Department of Texas Agricultural Agriculture Experiment Station and Soil Survey of Texas State Soil and Water Natural Conservation Board Brazos County, Resources Conservation Service Texas 3 How To Use This Soil Survey General Soil Map The general soil map, which is a color map, shows the survey area divided into groups of associated soils called general soil map units. This map is useful in planning the use and management of large areas. To find information about your area of interest, locate that area on the map, identify the name of the map unit in the area on the color-coded map legend, then refer to the section General Soil Map Units for a general description of the soils in your area. Detailed Soil Maps The detailed soil maps can be useful in planning the use and management of small areas. To find information about your area of interest, locate that area on the Index to Map Sheets. Note the number of the map sheet and turn to that sheet. Locate your area of interest on the map sheet. Note the map unit symbols that are in that area. Turn to the Contents, which lists the map units by symbol and name and shows the page where each map unit is described. The Contents shows which table has data on a specific land use for each detailed soil map unit. Also see the Contents for sections of this publication that may address your specific needs. 4 This soil survey is a publication of the National Cooperative Soil Survey, a joint effort of the United States Department of Agriculture and other Federal agencies, State agencies including the Agricultural Experiment Stations, and local agencies. -

Grimes County Health Services Directory

Grimes County Health Services Directory 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Emergency Numbers ............................................................................ 1 Police ............................................................................................. 1 Fire ................................................................................................ 1 Ambulance .................................................................................... 1 Sheriff’s Department ..................................................................... 1 Texas Highway Patrol ................................................................... 1 Other Emergency Numbers ................................................................. 2 Health Services ..................................................................................... 5 Ambulance/Emergency Medical Services ..................................... 5 Audiologists .................................................................................. 5 Chiropractors ................................................................................. 5 Counseling/Mental Health ............................................................. 5 Dentists .......................................................................................... 5 Diabetic Supplies .......................................................................... 6 DNA and Drug Testing ................................................................. 6 Fitness .......................................................................................... -

Anderson County UWCD 2007 Management Plan

ANDERSON COUNTY UNDERGROUND WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICT 2007-2012 Water Management Plan Adopted: July 12, 2007 450 ACR 409, Palestine, Texas 75803 903-729-8066 [email protected] Anderson County Underground Water Conservation District Water Management Plan 2007-2012 CREATION OF THE DISTRICT The Anderson County Underground Water Conservation District is created under the authority ofArticle XVI, Section 59, ofthe Texas Constitution by Senate Bill 1518 on May 15, 1989. RIGHTS, POWERS AND DUTIES OF THE DISTRICT The district was originally governed by Chapter 52, Texas Water Code, which was repealed by the 74th Legislature in 1995. The district is now governed by and subject to Chapter 36, Texas Water Code, and has all the powers, duties, authorities and responsibilities provided by Chapter 36, Texas Water Code. The district is also governed by the Texas Administrative Code: Title 31 Natural Resources and Conservation, Part 10 Texas Water Development Board, Chapter 356 Groundwater Management. 1. The district may prohibit the pumping or use ofgroundwater ifthe district determinesthat the pumpingwould present an unreasonable risk ofpollution. 2. The district may limit the pumping ofgroundwater to uses determined by the board to benefit the district. 3. The district may requirepersonsholdinga permit for an injectionwell to purchase water from the district. 4. The district may adopt regulationsfor the disposal ofsalt dome leachate in the district or may require disposal ofsalt dome leachate outside the district. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Qualifications To be qualified for election as a director, a person must be: 1. a resident ofthe district, 2. at least 18 years ofage; and 3. not otherwise disqualified by Section 50.026, Water Code Composition ofthe Board The board ofthe district is composed ofnine members. -

Texas Continuum of Care Regions 2018

Dallam Sherman Hansford Ochiltree Lipscomb Texas Hartley Moore Hutchinson Roberts Hemphill Oldham Potter Carson Gray Wheeler Continuum of Care Collings- Deaf Smith Randall Armstrong Donley worth Childress Regions Parmer Castro Swisher Briscoe Hall Hardeman Bailey Lamb Hale Floyd Motley Cottle 2018 Foard Wilbarger Wichita Clay Montague Lamar Red River Cochran Hockley Lubbock Crosby Dickens King Knox Baylor Archer Cooke Grayson Fannin Delta Bowie Franklin Morris Throck- Jack Wise Denton Titus Yoakum Terry Lynn Garza Kent Stonewall Young Collin Hopkins Haskell morton Hunt Cass Camp Rockwall Rains Marion Shackel- Parker Tarrant Dallas Wood Upshur Gaines Scurry Jones Stephens Palo Pinto Dawson Borden Fisher ford Kaufman Harrison Gregg Van Zandt Hood Johnson Ellis Smith Martin Mitchell Eastland Andrews Howard Nolan Taylor Callahan Erath Somervell Henderson Panola Rusk Hill Navarro Comanche Bosque Cherokee El Paso Loving Winkler Ector Midland Glasscock Sterling Coke Runnels Coleman Anderson Brown Shelby Hamilton Freestone Nacogdoches McLennan Ward Mills San Limestone Augustine Hudspeth Culberson Crane Tom Coryell Upton Reagan Green Concho Houston Reeves Irion Falls Leon Angelina Sabine McCulloch Lampasas San Saba Trinity Bell Newton Robertson Madison Jasper Schleicher Menard Burnet Polk Pecos Milam Walker Tyler Jeff Davis Mason Brazos Llano Williamson Grimes San Crockett Burleson Jacinto Sutton Kimble Gillespie Travis Lee Montgomery Hardin Blanco Terrell Washington Orange Bastrop Kerr Hays Waller Liberty Presidio Val Verde Edwards Kendall Austin -

Available Funds for Economic Disaster Recovery

Brazos Valley Regional Economic Disaster Resiliency LEON Continuity of ROBERTSON Operations Plan MADISON BRAZOS GRIMES BURLESON WASHINGTON PRPC NORTEX SPAG TEXOMA ARK-TEX WCTCOG NCTCOG ETCOG PBRPC HOTCOG CTCOG CVCOG DETCOG CAPCOG RGCOG SETRPC MRGDC H-GAC AACOG GCRPC RESILIENCY PLAN FOR: CBCOG STDC LRGVDC (YOUR BUSINESS NAME) Economic Disaster Resiliency Plan | Brazos Valley Council of Governments Table of Contents Objectives of Economic Disaster Resiliency Continuity of Operations Plan ................................................. 1 Economic Disaster Resiliency Planning Process ............................................................................................ 1 Risk Assessment ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Business Impact Analysis (BIA) .................................................................................................................. 3 Risk Management ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Business Continuity Plan ....................................................................................................................... 4 COVID-19 Risk Management ................................................................................................................. 5 Step 1: About Your Business ........................................................................................................................ -

Notice of Public Meeting

THE STATE OF TEXAS cour,.'TY OF McLENNAN r l\4eetln" n CQP)' of which is llttached This is to certify thol th.• r:i::•trn :oard at th~ Co11r1 hou••,,. required he.reto, was posted on the oflicia u e \ ID ~D by Article 62.52-17 V. T. C. S. d ,.,., , 20_(7_ Execute on_!.---:..::...---· J. A. "Andy" Horwell, Co,,r,;; Clerk McLennct11an Cou ty, Texas By ~ ·Q,J)/.AIL.!Deputy Waco Metropolitan Planning Organization NOTICE OF PUBLIC MEETING POLICY BOARD OF THE WACO METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION, AND THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF WACO, TEXAS 10:00 A.M. Friday, January 17, 2020 South Waco Community Center 2815 Speight Ave Waco, Texas AGENDA I. Gall to Order, Proof of Posting. II. Public Hearing regarding any discussion or action item on this agenda. In accordance with requirements identified in Section 551.007 of the Texas Government Code, the public is permitted to address the Policy Board regarding any action or discussion item identified on this agenda. Ill. Approval of the November 21, 2019 meeting minutes. IV. Presentation to Councilman Dillon Meek in appreciation for his service as chair of the Waco MPO Policy Board during fiscal years 2018 and 2019. V. Consideration and Action regarding approval of Resolution 2020-1: Adoption of Connections 2045: The Waco Metropolitan Transportation Plan . A. Staff Presentation B. Public Hearing C. Consideration and Action P.O. Box 2570, Waco, TX 76702-2570 (254) 750-5650 www.waco-texas.com/cms-m po m [email protected] VI. Consideration and Action regarding approval of Resolution 2020-2: Appointment of an MPO representative to the Heart of Texas Regional Transportation Coordination Council. -

FALL 1969 Bulletin 17 RAYMOND L

BAYLOR FALL 1969 Bulletin 17 The Evolution of the Leon River System RAYMOND L JR. thinking is more important than elaborate FRANK PH.D. PROFESSOR OF GEOLOGY BAYLOR UNIVERSITY 1929-1934 Objectives of Geological Training at Baylor The training of a geologist in a university covers but a few years; his education continues throughout his active The purposes of training geologists at Baylor University are to provide a sound basis of understanding and to foster a truly geological point of view, both of which are essential for continued pro fessional growth. The staff considers geology to be unique among sciences since it is primarily a field science. All geologic research in cluding that done in laboratories must be firmly supported by field observations. The student is encouraged to develop an inquiring objective attitude and to examine critically all geological concepts and principles. The development of a mature and professional attitude toward geology and geological research is a principal concern of the department. THE BAYLOR UNIVERSITY PRESS TEXAS BAYLOR GEOLOGICAL STUDIES BULLETIN NO. 17 The Geomorphic Evolution of the Leon River System RAYMOND L JR. BAYLOR UNIVERSITY Department of Geology Waco, Texas Fall, 1969 Baylor Geological Studies EDITORIAL STAFF Jean M. Spencer, M.S., Editor environmental and medical geology O. T. Hayward, Ph.D., Advisor, Cartographic Editor stratigraphy-sedimentation, structure, geophysics-petroleum, groundwater R. L. M.A., Business Manager archeology, geomorphology, vertebrate paleontology James W. Dixon, Jr., Ph.D. stratigraphy, paleontology, structure Walter T. Huang, Ph.D. mineralogy, petrology, metallic minerals Gustavo A. Morales, Ph.D. micropaleontology, stratigraphy STUDENT EDITORIAL STAFF Lawrence W. -

Brazos County Hazard Mitigation Plan

Brazos County Hazard Mitigation Mitigating Risk: Protecting Brazos County from All Hazards 2012-2017 Department of Emergency Management 110 N. Main Street Suite 100 Bryan, Texas 77803 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PURPOSE AND PROCESS OF DEVELOPMENT This update document, “Mitigating Risk: Protecting Brazos County from All Hazards, 2012 – 2017,” was prepared by the jurisdictions within Brazos County with the support of the Brazos Valley Council of Governments (BVCOG) and its contractor, the Texas Engineering Extension Service (TEEX). This plan is a five-year blueprint for the future, aimed at making communities in Brazos County disaster resistant by reducing or eliminating the long-term risk of loss of life and property from the full range of natural disasters. It meets the requirements of the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-390); Section 44 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 201.6 and Part 206; and State of Texas Division of Emergency Management standards. An open public process was established to provide multiple opportunities for all sectors in Brazos County to become involved in the planning process and make input during its drafting stage. HAZARDS FACING BRAZOS COUNTY The plan identifies and assesses the potential impact of ten natural hazards that threaten Brazos County. These include: dam failures; drought; excessive heat; fires; floods; hail; hurricanes; severe winter storms; thunderstorms; and tornadoes. Hazards were identified based on a review of historical records, national data sources, existing plans and reports, and discussions with local, regional, and national experts. Each hazard was profiled based on its severity of impact, frequency of occurrence, seasonal patterns, warning time, cascading potential and existing warning systems.