Volume 10 Number 03

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

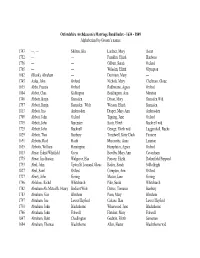

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

A Message from Jean Andrews

Eynsham Baptist Church May 2012 Newsletter Eynsham Baptist Church Lombard Street, Eynsham, Oxford OX29 4HT Tel: 01865 882203 Email: [email protected] Minister – Rev. Jean Andrews SUNDAY SERVICES All services are at 10.30 a.m. unless stated otherwise. Morning services include Creche and Junior Church. Prayer Meeting every Sunday at 10.00 a.m. in the church before the service. DATE THEME READINGS LEADER His Life in One Chapter 6th May Economic Security Luke 18:18-30 Bob Thiele 4.00 p.m. Hungarian Mother's Day Rev Zoltan Biro Service 13th May As He was saying Luke 18:31-34 Rev Jean Andrews HC Songs of Praise Service for Christian Aid Week. 3.00 p.m. Service followed by tea and an opportunity to choose a Maureen Thompson favourite hymn for possible inclusion in a future service. Everyone welcome. th 20 May What we really need Luke 18: 35-43 Rev Jean Andrews The Early Church th 27 May HC Happy Birthday Acts 2 Team Pentecost Baptismal Service + Commissioning of (English/Hungarian) Deacons EBC at Active Prayer Lord of all eagerness, be there at our labours & our merry making. We praise You for all the abilities & skills You have given us and ask they may be fully used as You direct. We remember all who have regular employment, that they are conscientious & reliable. For those who have not, that they may be patient and persistent in their job seeking. May those made redundant or retired early who have financial or other problems, have courage to re-adjust to a new lifestyle. -

Decision by West Oxfordshire District Council in Response to a Proposal by British Telecommunications Plc for the Re

Schedule - Decision by West Oxfordshire District Council in response to a proposal by British Telecommunications plc for the removal of public call boxes pursuant to Part 2 of the Schedule to a Direction published by Ofcom on 14 March 2006 ('the Direction'). FINAL DECISION Number of calls Posting Agree/ Telephone in last 12 Completed Adopt/ Number Address Post Code months Date Object Comments/Reasons PCO THE GREEN CLANFIELD Low level of usage. Mobile reception in the area is good for all major networks. Socio-economic factors do not justify 01367810230 BAMPTON OX18 2SR 0 05/10/2016 Agree retention. IN LAY BY BULLS CLOSE FILKINS 01367860201 LECHLADE GL7 3HY 30 05/10/2016 Object Relatively high level of usage. Proximity to social housing. PCO BROADWELL ROAD Low level of usage. Mobile reception in the area is good for all major networks. Socio-economic factors do not justify 01367860219 LANGFORD LECHLADE GL7 3LP 0 05/10/2016 Agree retention. NEAR P O COOKS LANE SALFORD 01608642567 CHIPPING NORTON OX7 5FG 0 03/10/2016 Agree Low level of usage. Mobile reception in the area is good for all major networks. PCO WORCESTER ROAD CHIPPING Low level of usage. Mobile reception in the area is good for all major networks. Socio-economic factors do not justify 01608642777 NORTON OX7 5XT 0 03/10/2016 Agree retention. Payphone provision will be left in the settlement after the removal. Low level of usage. Mobile reception in the area is good for all major networks. Socio-economic factors do not justify 01608658268 PCO FOSCOT CHIPPING NORTON OX7 6RH 0 03/10/2016 Agree retention. -

Winter 2010 FREE – Please Take One

Issue 43 – Winter 2010 FREE – Please take one Newsletter of North Oxfordshire Branch of CAMRA Use Them Or Lose Them Over the last 15 years or so A sign of the times – 28 pubs in the Branch has permanently our Branch are currently up for lost about 12 pubs; roughly sale … and that’s just the ones we know about one every 15 months. Some old favourites like the White still working with locals Hart, Charlbury; King’s Head, in Leafield to save The Tackley; and Chequers, North Fox (see page 3) and Newington – places where past monitoring the Albion, generations had their first legal Chipping Norton which pint or wet their first-born’s head has had an application are now gone forever. There for demolition submit- are about half a dozen pubs ted to the planning that are shut, but have not been department. The Bishop on November 4th and some granted change of use, like the Blaize, Burdrop is now up for local knowledge, there are cur- Marlborough Arms, Banbury and sale, but that situation still needs rently some 29 pubs out of the the Plough, Merton. This last to be watched. The Cricketers, total of about 235 pubs closed. year though has seen a change Banbury will almost certainly These include The Swan, Ascott- with the loss of the Blacklock become housing next year hav- under-Wychwood and Off the Arms to Tesco and the Branch ing had an application to convert Beaten Track, Chipping Norton. locked in four battles to save to flats approved. A few hours one morning spent pubs; with the Whitmore Arms In addition to this, according surfing the net found 28 iden- now safe (see page 29), we are to the local CAMRA website tifiable pubs for sale, including the Red Lion, Cropredy, both Our Popular Periodical Perused Middle Barton pubs (The Fox and the Carpenters) and the In Phuket Dun Cow, Hornton. -

1273805 W Oxford DC Planning X56.Indd

WEST OXFORDSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL Town and Country Planning Acts require the following to be advertised 18/01488/LBC WITNEY LBC. 35A High Street Witney Oxfordshire 18/01562/LBC WOODSTOCK. CONLB Woodstock House Rectory Lane Woodstock 18/01803/FUL MINSTER LOVELL CONLB. Rosery Old Minster Lovell Minster Lovell 18/01563/HHD WITNEY CONLB. Oriel House 10A Church Green Witney 18/01564/LBC WITNEY LBC. Oriel House 10A Church Green Witney 18/01600/FUL WITNEY CONLB. Store To Rear 8 - 10 Market Square Witney 18/01601/HHD LANGFORD CONLB. Faircroft Filkins Road Langford 18/01523/FUL CHILSON CONLB. Pudlicote House Pudlicote Lane Chilson 18/01539/RES BRIZE NORTON MAJ. Land East Of Monahan Way Carterton 18/01582/HHD FIFIELD CONLB. 2 Church Street Fifield Chipping Norton 18/01715/HHD SPELSBURY CONLB.The Barn Cottage Dean Chipping Norton 18/01660/HHD FULBROOK CONLB. Fulbrook Manor Upper End Fulbrook 18/01704/HHD HANBOROUGH CONLB.The Old Rectory Church Road Church Hanborough 18/01587/FUL WOODSTOCK CONLB. Coach House Woodstock House Rectory Lane 18/01649/LBC IDBURY LBC. Idbury Manor Church Street Idbury 18/01828/HHD BURFORD CONLB. 1 The Leaze Barns Lane Burford 18/01647/FUL STANTON HARCOURT CONLB.The Bungalow Blackditch Stanton Harcourt 18/01800/HHD SHIPTON UNDER WYCHWOOD CONLB. 3 Bradleys Shipton Under Wychwood Chipping Norton 18/01611/FUL STANTON HARCOURT CONLB/DEP/MAJ/PROW. Land At Former Stanton Harcourt Airfield Main Road Stanton Harcourt 18/01661/LBC FULBROOK LBC. Fulbrook Manor Upper End Fulbrook CODE KEY: ADDINF Additional Information Received. ADESC Amended description. AMDINF Amended Information Received. CONLB Conservation Area or Listed Building – affecting. -

October 2020

Hanborough Herald October 2020. No. 430 Legacy of War: Remembering a Hanborough Victim of a Flying Bomb Contents Parish Council pages 2-3 Waste & Recycling page 4 Eynsham Medical Group page 5 Scouts & Guides page 8 The Commonwealth War Graves at Christ Church, Long Hanborough. Middle: Winifred Ward’s Headstone. U3A anborough residents may be aware that in June. page 9 H addition to the names of the war dead Coleman Court is a large 1930s apartment inscribed on the village war memorial, there block close to Southfields Underground sta- Wildlife Habitats page 10 are four Commonwealth War Graves in the tion, and flat 121 is on the top floor. What graveyard of Christ Church. One from the struck Winifred’s flat that day was not a con- Catholic Church First World War (Pte J. Gessey, Ox & Bucks ventional bomb but a V-1 missile, one of Hit- page 11 Light Infantry) and three from the Second ler’s terror weapons introduced towards the Community Tree Project World War (Pte H. H. Lovell, Pioneer Corps; end of the war. The V-1s—also known as page 12 Flt Sgt A. H. Richards, RAF; Corp E. W. Long, RAF). Details of each can be found on Bus Museum the Commonwealth War Graves Commis- page 13 sion website (www.cwgc.com). Hanborough Pre-School But close by is another, non-military, head- page 14 stone with a wartime connection. It is rather neglected and tucked away on the eastern Running Group page 16 edge of the churchyard. The inscription reads: C of E & United IN LOVING MEMORY OF WINIFRED The V-1 missile was 25 feet long, powered by a jet engine and carried an Churches ALICE WARD BELOVED WIFE OF 1,870 lb. -

Alphabetized by Groom's Names

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Alphabetized by Groom’s names 1743 ---, --- Shilton, Bks Lardner, Mary Ascot 1752 --- --- Franklin, Elizth Hanboro 1756 --- --- Gilbert, Sarah Oxford 1765 --- --- Wilsden, Elizth Glympton 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1745 Aales, John Oxford Nichols, Mary Cheltnam, Glouc 1635 Abba, Francis Oxford Radbourne, Agnes Oxford 1804 Abbot, Chas Kidlington Boddington, Ann Marston 1746 Abbott, Benjn Ramsden Dixon, Mary Ramsden Wid 1757 Abbott, Benjn Ramsden Widr Weston, Elizth Ramsden 1813 Abbott, Jno Ambrosden Draper, Mary Ann Ambrosden 1709 Abbott, John Oxford Tipping, Jane Oxford 1719 Abbott, John Burcester Scott, Elizth Bucknell wid 1725 Abbott, John Bucknell George, Elizth wid Luggershall, Bucks 1829 Abbott, Thos Banbury Treadwell, Kitty Clark Finmere 1691 Abbotts, Ricd Heath Marcombe, Anne Launton 1635 Abbotts, William Hensington Humphries, Agnes Oxford 1813 Abear, Edmd Whitfield Greys Bowlby, Mary Ann Caversham 1775 Abear, Jno Burton Walgrove, Bks Piercey, Elizth Rotherfield Peppard 1793 Abel, John Upton St Leonard, Glouc Bailey, Sarah St Rollright 1827 Abel, Saml Oxford Compton, Ann Oxford 1727 Abery, John Goring Mason, Jane Goring 1796 Ablolom, Richd Whitchurch Pike, Sarah Whitchurch 1742 Abraham Als Metcalfe, Henry Bodicot Widr Dawes, Tomasin Banbury 1783 Abraham, Geo Bloxham Penn, Mary Bloxham 1797 Abraham, Jno Lower Heyford Calcote, Han Lower Heyford 1730 Abraham, John Blackthorne Whorwood, Jane Blackthorne 1766 Abraham, John Fritwell Fletcher, Mary Fritwell 1847 -

Volume 15 Number 07

CAKE AND COCKHORSE BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY AutumnNinter 2002 €2.50 Volume 15 Number 7 ISSN 6522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Registered Charity No. 260581 President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman: Brim Little, 12 Longfellow Road, Banbury OX16 9LB (tel. 01295 264972). Cake and Cockhorse Editorial Committee Jererny Gibson (as below), Deborah Hayter, Beryl Hudson Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: Simon Townsend, G.F. Grifiths, Banbury Museum, 39 Waller Drive, Spiceball Park Road, Banbury, Banbury OX 16 2PQ Oxon. OX16 9NS; (tel. 01295 672626) (tel. 01295 263944) Programme Secretary: Hon. Research Adviser: R.N.J. Allen, J.S.W. Gibson, Barn End, Keyte's Close Harts Cottage, Adderbury, Church Hanborough, Banbury, Oxon. OX 17 3PB Witney, Oxon. OX29 SAB; (tel. 01295 81 1087) (tel. 01993 882982). Committee Members: Colin Cohen, Mrs D. Hayter, Miss B.P. Hudson, Miss K. Smith, Mrs F. Thompson. Membership Secretary: Mrs Margaret Little, Clo Banbury Museum, Spiceball Park Road, Banbury, Oxon. OX 16 2PQ. Details of the Society's activities and publications will be found inside the back cover. Cake and Cockhorse The magazine of the Banbury Historical Society, issued three times a year. Volume 15 Number Seven AutumnWinter 2002 Kenneth R.S. Brooks Aplins - The Oldest Solicitors’ Practice in Banbury. Part Two. The Twentieth Century ... ... 214 N.J. Mayhew and E.M. Besly The 1996 Broughton Coin Hoard ... 233 Chris Pickford Bells, Bellringing and Bellhangers at and from Kings Sutton ... ... ... ... 240 -. - ....... - . Brian Little Lecture Reports ... ... ... ... 246 _. - - ... - ... - -_ First, our apology to our distinguished correspondent Christopher Hall, editor. of the excellent Oxfordshire Local History (Oxfordshire Local History Association) whose surname in an aberration we rendered as ‘Hill’; causing confusion with our even better-known former member and neighbour at Sibford who has spoken memorably to our Society on several occasions. -

Hanborough Station Transport Infrastructure Study Baseline Review

West Oxfordshire District Council Hanborough Station Transport Infrastructure Study Baseline Review September 2019 Hanborough Station Infrastructure Study – Baseline Review Hanborough Station Transport Infrastructure Study Baseline Review Version 3-0 September 2019 Produced by: For: Contact: Geoff Burrage Integrated Transport Planning Ltd. 6 Hay’s Lane London Bridge London SE1 2HB UNITED KINGDOM 0203 300 1810 [email protected] www.itpworld.net ii Hanborough Station Infrastructure Study – Baseline Review Project Information Sheet Client West Oxfordshire District Council Project Code 2849 Project Name Hanborough Station Transport Infrastructure Study Project Director Neil Taylor Project Manager Geoff Burrage Quality Manager Neil Taylor Additional Team Members Sandy Moller, Lewis McAuliffe Sub-Consultants N/A Start Date 2nd March 2019 File Location F:\2800-2899\2849 Hanborough Station Transport Infrastructure Study\Project Files\Baseline Document Control Sheet Ver. Project Folder Description Prep. Rev. App. Date V3-0 F:\2800-2899\2849 Final LM GB NT 30/09/2019 V2-0 F:\2800-2899\2849 Final draft for LM GB NT 13/09/2019 OCC review V1-2 F:\2800-2899\2849 Final draft for LM GB NT 03/06/2019 WOCC review V1-1 F:\2800-2899\2849 Final draft for LM GB NT 27/05/2019 WODC review V1-0 F:\2800-2899\2849 Draft LM GB - 15/05/2019 Notice This report has been prepared for West Oxfordshire District Council in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment. Integrated Transport Planning Ltd cannot accept any responsibility for any use of or reliance on the contents of this report by any third party. iii Hanborough Station Infrastructure Study – Baseline Review Table of Contents 1. -

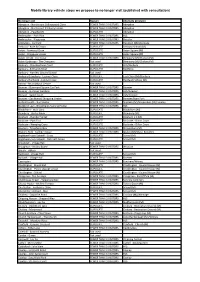

Mobile Library Vehicle Stops We Propose to No Longer Visit (Published with Consultation)

Mobile library vehicle stops we propose to no longer visit (published with consultation) No longer visit Reason Alternate provision Abingdon - Northcourt Collingwood Close FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Abingdon Abingdon - Northcourt Fitzharry's Arms FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Abingdon Abingdon - Peachcroft DUPLICATE Abingdon Ambrosden - Park Rise FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS HLS Ambrosden - Playgroup FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Bicester Ardington - Car Park FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Hendred (M)/Wantage Ashbury - Rose & Crown DUPLICATE Ashbury School (M) Aston - Foxwood Close DUPLICATE Aston Square (M) Aston - Kingsgate House DUPLICATE Aston Square (M) Aston Tirrold - The Close FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Blewbury (M)/Cholsey (M) Aston Upthorpe - The Chequers Not used Blewbury (M)/Cholsey (M) Banbury - Chamberlaine Court DUPLICATE HLS/Banbury Banbury - Edmunds Road DUPLICATE Neithrop Banbury - Harriers Ground School Not used Banbury Grimsbury - Levinot Close DUPLICATE East Close (M)/Banbury Banbury Hardwick - Juniper Close DUPLICATE Hardwick School (M) Barton - Roundabout Centre Not used Bicester - Bowmont Square Car Park FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Bicester Bicester - Hanover Gardens FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS HLS/Bicester Bicester - Saxon Court FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS HLS/Bicester Bicester - Southwold Shopping Centre FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Bicester/Bure Park Binfield Heath - Bus Shelter FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS Shiplake (M)/Harpesden (M)/ Henley Blackbird Leys - Brookfields Nursing Home FEWER THAN 3 VISITORS HLS Blackthorn - Weir Lane DUPLICATE Blackthorn (M) Blewbury - Barley Mow DUPLICATE -

Consultation Document

Witney and Chipping Norton Area Review New contracts to commence June 2014 A: Contracts under review in Witney and Woodstock area Service Contract Days of ITEM Route Operator Page number number operation A 11 W11 Witney – Freeland – Oxford Mon-Sat Stagecoach 2 B 18 W4 Bampton – Oxford Mon-Sat Stagecoach 3 Witney – Bampton – Carterton – C 19 W4 Mon-Sat Stagecoach 4 Shilton Park D 64 W10 Carterton – Swindon Mon-Sat Stagecoach 5 E 113 W12 Fulbrook – Carterton – Faringdon Thurs only Pulhams 6 213/214/ F W3 Witney town services Mon-Sat Stagecoach 7 215 G 233 W6 Milton under Wychwood – Witney Mon-Sat Stagecoach 8 Witney – Burford – Kingham Stn – H 233 W44 Sun/BH Stagecoach 9 Chipping Norton I 242 W28 Woodstock – Witney Mon-Sat Stagecoach 10 J X15 W21 Abingdon – Witney Mon-Sat Stagecoach 11 20 W14 Swinbrook – Witney Thurs only 24 W15 Ascott – Witney Thurs only K Villager 12 21 W18 Idbury – Witney Weds only 14 W19 Leafield – Witney Tue only 223/224/ L W47 Kidlington local services Mon-Sat Heyfordian 13 224A Mon-Fri 203/220/ M W47 ‘Woodstock Wanderer’ plus single Heyfordian 14 242 Sat journey B: Contracts under review in Chipping Norton area Service Contract Days of ITEM Route Operator Page number number operation Steeple Aston – Tews – Chipping N 23A W43 Weds only Heyfordian 15 Norton O 243 W48 Combe – Leafield – Witney Tues/Fri Pulhams 16 Salford – Chipping Norton – P 811 W49 Sat only Pulhams 17 Cheltenham Mon-Fri Q C1/T1 W39 Charlbury Railbus/Taxibus Go-Ride 18/19 R X8 W50 Kingham Railbus Mon-Sat Pulhams 20/21 S X8A W52 Wychwoods – Kingham Station Mon-Sat Go-Ride 22/23 Mon-Sat plus W45/ T X9 Witney – Charlbury – Chipping Norton Fri/Sat eves.