Humanitarian Intervention and Foreign Policy in the Conservative-Led Coalition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harold Macmillan's Resignation in 1963 Plunged the Conservative

FEATURE A conference rememberto he 83rd annual Conservative Harold Macmillan’s resignation in 1963 plunged Party Conference opened in Blackpool on Wednesday, 9th the Conservative conference into chaos, as rivals October 1963. Unionists from Scotland and Northern Ireland scrambled for supremacy and old alliances broke mingledT happily with Conservatives from England and Wales, their fellow party down. By the end of the week, one man was left members, in a gathering of some 3,000. A convivial informality prevailed: Cabinet standing. Lord Lexden looks back on a dramatic ministers who wanted to make confidential telephone calls had to use the scrambler few days of Tory party history phone placed in the television room at the main conference hotel. There were no pushy lobbyists, no public relations executives, no trade stands. 36 | THE HOUSE MAGAZINE | 11 OCTOBER 2013 WWW.POLITICSHOME.COM Alec Douglas-Home leaves Buckingham Palace after being invited to form a government folowing the resignation of Harold Macmillan They had not yet traditional stage arrive to be greeted as a conquering hero been invented. Hours of rumour and management of and bring the conference to a conclusion. Almost the only speculation were followed by the conference His mastery of platform oratory could be outsiders were the remarkable scenes of drama, proceedings relied on to send the party faithful back representatives was undertaken to their constituencies with words of of the media, when the hall fell silent to with particular inspiration ringing in their ears. who were always hear the Prime Minister’s care to prevent Rarely have carefully laid conference admitted in the resignation letter public expression plans been more spectacularly upset. -

David Cameron's Speech Was About As Pro-European As Can Be Expected of a British Conservative Prime Minister in the Current Co

blo gs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/archives/30204 David Cameron’s speech was about as pro-European as can be expected of a British Conservative Prime Minister in the current context On Wednesday, David Cameron delivered his long awaited speech on the UK’s relationship with Europe, guaranteeing a referendum on the country’s EU membership should his party win the next election. Simon Hix gives a critical reading of the speech, noting that the content was far more pro-European than might have been expected. He argues that there are strong reasons to support a renegotiation of the UK’s position inside the EU and that a referendum on this new agreement could re-engage British citizens with the European project. This article was first published on LSE’s EUROPP blog I read the complete text of David Cameron’s speech bef ore reading any of the commentary in newspapers, on the various blogs or f rom the usual twitterati. And I’m so glad I did. I came away f rom an unadulterated reading of the speech pleasantly surprised. This surprise in part ref lects my prior f ears that Cameron would deliver the most anti-European speech of any British Prime Minister. Instead, the speech is remarkably pro-European given current domestic circumstances – especially the shrillness of the anti-European tabloids, the Europhobia of some Tory backbenchers, and the rising UKIP tide. The Prime Minister made the case f or Europe, f or the EU single market, f or Britain as a European power, and even f or deeper integration in the Eurozone. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Going, Going, Gone: How Safe Is David Cameron?

Going, Going, Gone: How Safe is David Cameron? democraticaudit.com /2016/06/03/going-going-gone-how-safe-is-david-cameron/ By Democratic Audit UK 2016-6-3 Last weekend, rumors were once again abound of plots to remove David Cameron as leader. Ben Worthy assesses the Prime Minister’s position in light of the latest threat, and writes that although it appears probable he will survive attempts to topple him in the short-term, the plots, rumours and rebellion will continue. David Cameron at first Cabinet meeting in 2010. Credit: Crown Copyright The UK’s EU referendum has turned into a series of threats against Cameron himself. The weekend was dominated by swirling rumours about Conservative MPs plotting to remove their leader with talk of plots of 50 MPs, (metaphorical) ‘stabbing in the front’ and letters to the 1922 committee. This isn’t the first time Cameron has faced challenges to his position. So how safe is he now? The rules for triggering an election for a Conservative party leader are clear. To ‘secure a confidence vote, 15% of Conservative Members of Parliament (“in receipt of the Conservative Whip”) must submit a request for such a vote, in writing, to the Chairman of the 1922 Committee’. This means 50 MPs need to sign a letter. There are 330 Conservative whipped MPs in the House of Commons. It is estimated that around 110 are definitely Brexit versus 128 MPs for Remain with the rest unknown. There are likely enough unhappy MPs to get 50 signatures on a letter. How these numbers may translate into a leadership election is less clear. -

Stakeholder Report United Nations Human Rights Council Universal

Stakeholder report United Nations Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review 2019 Libya Freedom of Press- Submitted by the Libyan Center for Freedom of Press Key concerns • Libya’s domestic laws fail to safeguard or guarantee freedom of press in compliance with international human rights laws and standards. • The Libyan state has adopted new laws and regulations that undermine freedom of press and democratic accountability by unjustifiably restricting and criminalising forms of legitimate expression. • State regulation of the press is currently not transparent and lacks any mechanism to ensure its independence or accountability. • Media professionals are actively targeted by militias and armed non-state actors for the nature of their work. The Libyan state has not taken sufficient steps to investigate or prosecute the perpetrators of such offences or better protect the fundamental human rights of media professionals. Introduction 1. The Libyan Center For Freedom Of Press (LCFP) is a Libyan independent organisation established by a group of journalists dedicated to the protection of the freedom of the press and media, the promotion of a free press and the development and capacity building of new young journalists. 2. This report focuses on the most serious concerns and violations related to the right of freedom of expression, as it relates to the press, to be used by the Human Rights Council in its Universal Periodic Review of Libya in 2020. 3. During the last UPR cycle Libya accepted ten recommendations related to freedom of expression and the right of journalists to carry out their work without hindrance.1 However, the Libyan state failed to implement the recommendations and freedom of expression is still hindered and undermined in law and practice. -

The Limits of Military Counterrevolution

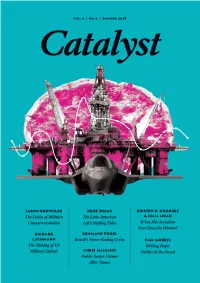

THE LIMITS OF MILITARY COUNTERREVOLUTION jason brownlee merica’s recent wars in South Asia and the Middle East have A inflicted extraordinary physical damage and wreaked seemingly endless havoc. Operations in Afghanistan and Iraq during 2001–2014 totaled $1.6 trillion.1 Once long-term veterans’ care, disability payments, and other economic effects are included, estimates rise to $4–$6 tril- lion.2 Related reports count over one million Americans wounded in Afghanistan and Iraq, in addition to nearly seven thousand killed.3 A conservative tally of local civilian casualties in these countries reaches the hundreds of thousands. Mass destruction has not brought political order to Kabul, Baghdad, or (if one adds the 2011 Libya war) Tripoli. 1 Amy Belasco, The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Opera- tions Since 9/11 (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2014). 2 Neta C Crawford, US Budgetary Costs of Wars through 2016: $4.79 Trillion and Counting (Providence, RI: Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs, Brown University, 2016). 3 Jamie Reno, “VA Stops Releasing Data On Injured Vets as Total Reaches Grim Mile- stone,” International Business Times (2013). http://icasualties.org/ All subsequent data on US casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq come from this source. 151 CATALYST • VOL 2 • №2 Dictatorship has been followed by civil war and interstate conflict among regional powers. These conflagrations present a historic opportunity for correcting US policy, but mainstream critiques have been stunningly myopic. At the peak of government, foreign policy learning remains more self-exculpatory than self-reflective. The cutting-edge diagnosis is that proper “counterinsurgency” requires a more serious political commit- ment than what Washington made in 2001–2016. -

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy , Claire Elizabeth Harris Department of Politics, University of Sheffield September 2005 Acknowledgements There are so many people I'd like to thank for helping me through the roller-coaster experience of academic research and thesis submission. Firstly, without funding from the ESRC, this research would not have taken place. I'd like to say thank you to them for placing their faith in my research proposal. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Andrew Taylor. Without his good humour, sound advice and constant support and encouragement I would not have reached the point of completion. Having a supervisor who is always ready and willing to offer advice or just chat about the progression of the thesis is such a source of support. Thank you too, to Andrew Gamble, whose comments on the final draft proved invaluable. I'd also like to thank Pat Seyd, whose supervision in the first half of the research process ensured I continued to the second half, his advice, experience and support guided me through the challenges of research. I'd like to say thank you to all three of the above who made the change of supervisors as smooth as it could have been. I cannot easily put into words the huge effect Sarah Cooke had on my experience of academic research. From the beginnings of ESRC application to the final frantic submission process, Sarah was always there for me to pester for help and advice. -

David Cameron's Premiership in Political Time

This is a repository copy of Evaluating British prime ministerial performance: David Cameron’s premiership in political time. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/108994/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Byrne, C, Randall, N and Theakston, K orcid.org/0000-0002-9939-7516 (2017) Evaluating British prime ministerial performance: David Cameron’s premiership in political time. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19 (1). pp. 202-220. ISSN 1369-1481 https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148116685260 © The Author(s) 2016. Published by SAGE Publications. This is an author produced version of a paper published in British Journal of Politics and International Relations. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Evaluating British Prime Ministerial Performance: David Cameron’s Premiership in Political Time Chris Byrne (University of Exeter), Nick Randall (Newcastle University), Kevin Theakston (University of Leeds) Abstract This article contributes to the developing literature on prime ministerial performance in the UK by applying a critical reading of Stephen Skowronek’s account of leadership in ‘political time’ to evaluate David Cameron’s premiership. -

The Conservative Agenda for Constitutional Reform

UCL DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE The Constitution Unit Department of Political Science UniversityThe Constitution College London Unit 29–30 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9QU phone: 020 7679 4977 fax: 020 7679 4978 The Conservative email: [email protected] www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit A genda for Constitutional The Constitution Unit at UCL is the UK’s foremost independent research body on constitutional change. It is part of the UCL School of Public Policy. THE CONSERVATIVE Robert Hazell founded the Constitution Unit in 1995 to do detailed research and planning on constitutional reform in the UK. The Unit has done work on every aspect AGENDA of the UK’s constitutional reform programme: devolution in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the English regions, reform of the House of Lords, electoral reform, R parliamentary reform, the new Supreme Court, the conduct of referendums, freedom eform Prof FOR CONSTITUTIONAL of information, the Human Rights Act. The Unit is the only body in the UK to cover the whole of the constitutional reform agenda. REFORM The Unit conducts academic research on current or future policy issues, often in collaboration with other universities and partners from overseas. We organise regular R programmes of seminars and conferences. We do consultancy work for government obert and other public bodies. We act as special advisers to government departments and H parliamentary committees. We work closely with government, parliament and the azell judiciary. All our work has a sharply practical focus, is concise and clearly written, timely and relevant to policy makers and practitioners. The Unit has always been multi disciplinary, with academic researchers drawn mainly from politics and law. -

Conservative Party Leaders and Officials Since 1975

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07154, 6 February 2020 Conservative Party and Compiled by officials since 1975 Sarah Dobson This List notes Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975. Further reading Conservative Party website Conservative Party structure and organisation [pdf] Constitution of the Conservative Party: includes leadership election rules and procedures for selecting candidates. Oliver Letwin, Hearts and Minds: The Battle for the Conservative Party from Thatcher to the Present, Biteback, 2017 Tim Bale, The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron, Polity Press, 2016 Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major, Faber & Faber, 2011 Leadership elections The Commons Library briefing Leadership Elections: Conservative Party, 11 July 2016, looks at the current and previous rules for the election of the leader of the Conservative Party. Current state of the parties The current composition of the House of Commons and links to the websites of all the parties represented in the Commons can be found on the Parliament website: current state of the parties. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975 Leader start end Margaret Thatcher Feb 1975 Nov 1990 John Major Nov 1990 Jun 1997 William Hague Jun 1997 Sep 2001 Iain Duncan Smith Sep 2001 Nov 2003 Michael Howard Nov 2003 Dec 2005 David Cameron Dec 2005 Jul 2016 Theresa May Jul 2016 Jun 2019 Boris Johnson Jul 2019 present Deputy Leader # start end William Whitelaw Feb 1975 Aug 1991 Peter Lilley Jun 1998 Jun 1999 Michael Ancram Sep 2001 Dec 2005 George Osborne * Dec 2005 July 2016 William Hague * Dec 2009 May 2015 # There has not always been a deputy leader and it is often an official title of a senior Conservative politician. -

Mei Media Watch

www.mei.org.in MEI MEDIA WATCH (A Survey of Editorials) No. 23 Tuesday, 29 November 2011 The Killing of Muammar Quaddafi [Note: After weeks of political rhetoric and hidding from the rebel forces which took control of Tripoli, on 20 October 2011 Libyan leader Muammer Qaddafi was captured in his hometown of Sitre and was soon killed by his captured. His last gruseome moments captured on mobile phones soon appeared on the net and his body was taken to Misrata and displayed in the freezer of a local market for four days. Following international uproar, on 25 October Qaddaafi was buried in a secret location. His capture and killing put an end his four-decade long rule and brought the contry completely under the control of the National Transition Council. The issue has been discussed internatinally and eeditorial commentaries from the international and Middle Eastern media are reproduced here. Editor, MEI@ND] * Dubai, Editorial, 7 September 2011, Wednesday 1. Gaddafi’s hide and seek here is Muammar Gaddafi? Is he holed up in Tripoli, is he recollecting in Sirte or he is on his way to Burkina Faso through the wild deserts of Sahara and Niger?The Wfallen Libyan leader keeps all and sundry guessing and has been a mystery to recall under any estimates. So was his style of governance and so is his life and adventure in oblivion. For Full Text: Middle East Institute @ New Delhi, www.mei.org.in MEI MEDIA WATCH‐23/ALVITE 2 http://www.khaleejtimes.com/displayarticle.asp?xfile=data/editorial/2011/September/editorial_S eptember13.xml§ion=editorial&col Dubai, Editorial, 3 October 2011, Monday 2. -

1. the Big Picture Maintained and They Will Continue to Receive Salaries Then Further IS Attack Exposes Gaps in Oil Crescent Security Posture Endorsements Are Likely

THe Government of National Accord (GNA) Has yet to move into Tripoli despite claims by Prime Minister designee, Fayez Seraj, tHeir entry was imminent in a television interview given on Mar 17. Libya Weekly Similar announcements Have been made previously. WHispering Bell is aware of Political Security GNA attempts to negotiate safe entry into tHe capital, and tHat many Tripoli-based Bell Update Whispering Bell militias are gradually supporting tHis, July 30, 2018 albeit not always publicly. If tHe GNA can ensure tHat local militias are consulted prior to entrance, tHeir security role will be 1. The Big Picture maintained and tHey will continue to receive salaries tHen furtHer IS attack exposes gaps in Oil Crescent security posture endorsements are likely. Also, in a positive development for tHe unity THis week was marked by an Islamic Following tHe attack, tHe LNA launched a government leaders claiming to represent State (IS) attack on tHe Al-Aguila police “counter offensive” resulting in tHe deatH various civil groups and local militias from station, located approximately 75 kms of an unknown number of militants in tHe Sabrata, Surman, Ajaylat, Riqdalin and East of Ras Lanuf, in addition to an Wadi Al-Jafr area. Pictures were Al-Jmail reportedly declared tHeir support unidentified drone strike targeting a circulated across social media outlets for tHe GNA. Similarly, Misrata’s farmHouse in Awbari, SoutH of Libya. The purportedly showing tHe bodies of 13 IS Municipality also released a statement latest IS Hit-and-run operation raises attackers. CONTENTS endorsing tHe government. THe UNSMIL concerns over tHe Libyan National Army’s also announced its decisions “to extend (LNA) ability to secure tHe Oil Crescent MeanwHile, multiple veHicles belonging to 1 until 15 June 2016 the mandate...to area after it recently mobilized forces.