UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Music Circulation And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 20/12/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 20/12/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Perfect - Ed Sheeran Grandma Got Run Over By A Reindeer - Elmo & All I Want For Christmas Is You - Mariah Carey Summer Nights - Grease Crazy - Patsy Cline Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Feliz Navidad - José Feliciano Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas - Michael Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Killing me Softly - The Fugees Don't Stop Believing - Journey Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Zombie - The Cranberries Baby, It's Cold Outside - Dean Martin Dancing Queen - ABBA Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Rockin' Around The Christmas Tree - Brenda Lee Girl Crush - Little Big Town Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi White Christmas - Bing Crosby Piano Man - Billy Joel Jackson - Johnny Cash Jingle Bell Rock - Bobby Helms Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Baby It's Cold Outside - Idina Menzel Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Let It Go - Idina Menzel I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Last Christmas - Wham! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! - Dean Martin You're A Mean One, Mr. Grinch - Thurl Ravenscroft Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Africa - Toto Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer - Alan Jackson Shallow - A Star is Born My Way - Frank Sinatra I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor The Christmas Song - Nat King Cole Wannabe - Spice Girls It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas - Dean Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Please Come Home For Christmas - The Eagles Wagon Wheel - -

Join Us on Facebook CONTACT

Join Us On Facebook PORTFOLIO OVERVIEW ad-network social endorsement media-plan sitelist CONTACT [email protected] for MEDIA ENQUIRIES [email protected] to JOIN OUR AD-NETWORK [email protected] for FINANCIAL ENQUIRIES *** Use hyperlinks to easy go to a specific sheet STATS RATECARD [RON] AD TYPES CONTENT BASED ADVERTISING Jan/16 DESKTOP MOBILE VIDEO DISPLAY MOBILE VIDEO MIN IO CONTENT BASED ADVERTISING DISPLAY MOBILE VIDEO ADVERT NEWSLETTER Customized ORIAL Customized MIN per PAGEVIEWS / UNIQUE USERS / PAGEVIEWS / UNIQUE USERS / VISITORS / Newsletter / No. Of Classic Newsletter / CATEGORY PRODUCT/CHANNEL VIEWS / MONTH CPM CPM CPM Insertion Advertorial Classic Insertion Direct other other other notes MONTH MONTH MONTH MONTH MONTH linear Subscribers Insertion Direct Mailing Order standard standard non-linear rich media rich media rich Mailing rising stars rising stars FACEBOOK 8,400,000 7,000,000 - marketplace ads facebook.com 8,400,000 7,000,000 - 25 25 25 4,500 - - - - - - mar- - - mar- - etpla - - - - INSTAGRAM - 1,100,000 - marketplace ads instagram.com - 1,100,000 - 25 25 25 4,500 - - - - - - mar- - - mar- - etpla - - - - LINKEDIN 1,880,000 - - marketplace ads linkedin.com 1,880,000 - - 25 25 25 4,500 - - - √ - - mar√ - - mar- - - - - - - DAILYMOTION.COM 26,584,590 921,312 7,258,203 333,308 12,277,938 921,312 entertainment dailymotion.com 26,584,590 921,312 7,258,203 333,308 12,277,938 921,312 45 45 45 9,000 - - - √ - √ 300 √ - √ - - √ √ - - - - SKYPE 187,594,469 1,339,758 102,926,964 1,010,343 - - communication -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura

The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura L. Bunting-Hudson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Laura L. Bunting-Hudson All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia Laura L. Bunting-Hudson How do rap artists in Bogota, Colombia come together to make music? What is the process they take to commodify their culture? Why are some rappers able to become socially mobile in this process, while others are less so? What is technology’s role in all of this? This ethnography explores those questions, as it carefully documents the strategies utilized by various rap groups in Bogota, Colombia to create social mobility, commoditize products and to create a different vision of modernity within the hip-hop community, as an alternative to the ideals set forth by mainstream Colombian society. Resistance Art Poetry (RAP), is said to have originated in the United States but has become a form of international music. In conducting ethnographic research from December of 2012 to October 2014, I was able to discover how rappers organize themselves politically, how they commoditize their products and distribute them to create various types of social mobilities. In this dissertation, I constructed models to typologize rap groups in Bogota, Colombia, which I call polities of rappers to discuss how these groups come together, take shape, make plans and execute them to reach their business goals. -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

Political Forum: 10 Questions on Georgia’S Political Development

1 The Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development Political Forum: 10 Questions on Georgia’s Political Development Tbilisi 2007 2 General editing Ghia Nodia English translation Kakhaber Dvalidze Language editing John Horan © CIPDD, November 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or oth- erwise, without the prior permission in writing from the proprietor. CIPDD welcomes the utilization and dissemination of the material included in this publication. This book was published with the financial support of the regional Think Tank Fund, part of Open Society Institute Budapest. The opinions it con- tains are solely those of the author(s) and do not reflect the position of the OSI. ISBN 978-99928-37-08-5 1 M. Aleksidze St., Tbilisi 0193 Georgia Tel: 334081; Fax: 334163 www.cipdd.org 3 Contents Foreword ................................................................................................ 5 Archil Abashidze .................................................................................. 8 David Aprasidze .................................................................................21 David Darchiashvili............................................................................ 33 Levan Gigineishvili ............................................................................ 50 Kakha Katsitadze ...............................................................................67 -

Ideologia Da Lingvisturi Ideebi IDEOLOGY and LINGUISTIC IDEAS

ggiorgiiorgi aaxvledianisxvledianis ssaxelobisaxelobis eenaTmecnierebisnaTmecnierebis iistoriisstoriis ssazogadoebaazogadoeba iivanevane jjavaxiSvilisavaxiSvilis ssaxelobisaxelobis TTbilisisbilisis ssaxelmwifoaxelmwifo uuniversitetiniversiteti ssaerTaSorisoaerTaSoriso kkonferenciaonferencia iideologiadeologia ddaa llingvisturiingvisturi iideebideebi IINTERNATIONALNTERNATIONAL CONFERENCECONFERENCE IIDEOLOGYDEOLOGY AANDND LLINGUISTICINGUISTIC IDEASIDEAS 6-9 ooqtomberi,qtomberi, 22017017 / OOCTOBERCTOBER 66-9,-9, 22017017 pprogramarograma ddaa TTezisebisezisebis kkrebulirebuli PProgramrogram aandnd AAbstractsbstracts TTbilisibilisi 22017017 gamomcemloba grifoni giorgi axvledianis saxelobis enaTmecnierebis istoriis sazogadoeba ivane javaxiSvilis saxelobis Tbilisis saxelmwifo universiteti saerTaSoriso konferencia ideologia da lingvisturi ideebi 6-9 oqtomberi, 2017, Tbilisi, saqarTvelo programa da Tezisebis krebuli TTbilisibilisi 22017017 GIORGI AKHVLEDIANI SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF LINGUISTICS IVANE JAVAKHISHVILI TBILISI STATE UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE IDEOLOGY AND LINGUISTIC IDEAS 6-9 OCTOBER, 2017, TBILISI, GEORGIA Program and Abstracts Tbilisi 2017 saredaqcio sabWo TinaTin bolqvaZe (ivane javaxiSvilis saxelobis Tbilisis saxelmwifo universiteti, giorgi axvledianis saxelobis enaTmecnierebis istoriis sazogadoeba, Tbilisi, saqarTvelo) patrik serio (peterburgis universiteti, ruseTi/ lozanis universiteti, Sveicaria) kamiel hamansi (adam mickeviCis universiteti, poznani, poloneTi) TinaTin margalitaZe (ivane javaxiSvilis saxelobis Tbilisis -

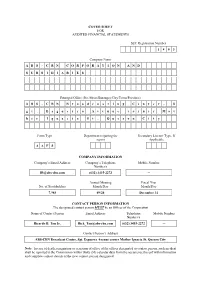

COVER SHEET for AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A

COVER SHEET FOR AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number 1 8 0 3 Company Name A B S - C B N C O R P O R A T I O N A N D S U B S I D I A R I E S Principal Office (No./Street/Barangay/City/Town/Province) A B S - C B N B r o a d c a s t i n g C e n t e r , S g t . E s g u e r r a A v e n u e c o r n e r M o t h e r I g n a c i a S t . Q u e z o n C i t y Form Type Department requiring the Secondary License Type, If report Applicable A A F S COMPANY INFORMATION Company’s Email Address Company’s Telephone Mobile Number Number/s [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Annual Meeting Fiscal Year No. of Stockholders Month/Day Month/Day 7,985 09/24 December 31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Mobile Number Number/s Ricardo B. Tan Jr. [email protected] (632) 3415-2272 ─ Contact Person’s Address ABS-CBN Broadcast Center, Sgt. Esguerra Avenue corner Mother Ignacia St. Quezon City Note: In case of death, resignation or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Constructing Multicultural Education in a Diverse Society I Ilghiz M

Constructing Mu lticuItu ral Education in a Diverse Society ILGHIZM. SINAGATULLIN A ScarecrowEducation Book The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanharn, Maryland, and London 2003 Published in partnership with the American Association of School Administrators A SCARECROWEDUCATIONBOOK Published in partnership with the American Association of School Administrators Published in the United States of America by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A Member of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.scarecroweducation.com 4 Pleydell Gardens, Folkestone Kent CT20 2DN, England Copyright 0 2003 by Ilghiz M. Sinagatullin All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-PublicationData Sinagatullin, Ilghiz M., 1954- Constructing multicultural education in a diverse society I Ilghiz M. Sinagatullin. p. cm. “A Scarecrow Education Book.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8108-4341-2 (cloth : alk. paper) - ISBN 0-8108-4340-4 (pbk.) 1. Multicultural education. 2. Educational anthropology. 3. Pluralism (Social sciences) I. Title. LC1099 .S55 2003 370.1174~21 2002003075 Printed in the United States of America @ TMThepaper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard