Batman, Argo, and Hollywood's Revolutionary Crowds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joker (2019 Film) - Wikipedia

Joker (2019 film) - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joker_(2019_film) Joker (2019 film) Joker is a 2019 American psychological thriller film directed by Todd Joker Phillips, who co-wrote the screenplay with Scott Silver. The film, based on DC Comics characters, stars Joaquin Phoenix as the Joker. An origin story set in 1981, the film follows Arthur Fleck, a failed stand-up comedian who turns to a life of crime and chaos in Gotham City. Robert De Niro, Zazie Beetz, Frances Conroy, Brett Cullen, Glenn Fleshler, Bill Camp, Shea Whigham, and Marc Maron appear in supporting roles. Joker was produced by Warner Bros. Pictures, DC Films, and Joint Effort in association with Bron Creative and Village Roadshow Pictures, and distributed by Warner Bros. Phillips conceived Joker in 2016 and wrote the script with Silver throughout 2017. The two were inspired by 1970s character studies and the films of Martin Scorsese, who was initially attached to the project as a producer. The graphic novel Batman: The Killing Joke (1988) was the basis for the premise, but Phillips and Silver otherwise did not look to specific comics for inspiration. Phoenix became attached in February 2018 and was cast that July, while the majority of the cast signed on by August. Theatrical release poster Principal photography took place in New York City, Jersey City, and Newark, from September to December 2018. It is the first live-action Directed by Todd Phillips theatrical Batman film to receive an R-rating from the Motion Picture Produced by Todd Phillips Association of America, due to its violent and disturbing content. -

Gotham Knights

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 11-1-2013 House of Cards Matthew R. Lieber University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Lieber, Matthew R., "House of Cards" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 367. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/367 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. House of Cards ____________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver ____________________________ In Partial Requirement of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ By Matthew R. Lieber November 2013 Advisor: Sheila Schroeder ©Copyright by Matthew R. Lieber 2013 All Rights Reserved Author: Matthew R. Lieber Title: House of Cards Advisor: Sheila Schroeder Degree Date: November 2013 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to approach adapting a comic book into a film in a unique way. With so many comic-to-film adaptations following the trends of action movies, my goal was to adapt the popular comic book, Batman, into a screenplay that is not an action film. The screenplay, House of Cards, follows the original character of Miranda Greene as she attempts to understand insanity in Gotham’s most famous criminal, the Joker. The research for this project includes a detailed look at the comic book’s publication history, as well as previous film adaptations of Batman, and Batman in other relevant media. -

The Dark Knight Rises Best Movie in Dark Knight Franchise by NICK BICHO Staff Writer

The Dark Knight Rises Best Movie in Dark Knight Franchise BY NICK BICHO Staff Writer Out of all the big budget, action packed blockbusters that came out this summer, none could have topped the hype and notoriety of The Dark Knight Rises. Starring Christian Bale and Anne Hathaway, The Dark Knight Rises is a tale of despair and redemption that cannot be missed. Director Christopher Nolan's final act in the series lives up to the hype and goes above and beyond the expectations set by the last movie. The plot is set eight years after The Dark Knight, at this time Bruce Wayne (Bale) is a broken man who lives in hiding while trying to deal with the consequences of his actions in the last movie. However, when a new villain comes to Gotham, Bruce Wayne must return as the Batman and save Gotham city once again. Christian Bale does an amazing job playing the part of Bruce Wayne. He’s able to capture the emotion, sorrow, and responsibility of the Batman. However Bale isn't the only one carrying this film. Actors Anne Hathaway and Joseph Gordon Levitt gave spectacular performances in their supporting roles. This movie has a lot of things going right. Other than the stellar performances of all of the actors, the story is deep and fits well with its predecessors. Director Christopher Nolan paints a dark and dreary Gotham city during the Batman's absence and it only gets worse when Bane shows up. Nolan perfectly tells The Batman's story and ends the series on a good note. -

Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 4-2-2016 “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Bosch, Brandon, "“Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films" (2016). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 287. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 17, ISSUE 1, PAGES 37–54 (2016) Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N Drawing on research on authoritarianism, this study analyzes the relationship between levels of threat in society and representations of crime, law, and order in mass media, with a particular emphasis on the superhero genre. -

Establishment and Implementation of a Conservation and Management Regime for High Seas Fisheries, with Focus on the Southeast Pacific and Chile

ESTABLISHMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF A CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT REGIME FOR HIGH SEAS FISHERIES, WITH FOCUS ON THE SOUTHEAST PACIFIC AND CHILE From Global Developments to Regional Challenges M. Cecilia Engler UN - Nippon Foundation Fellow 2006-2007 ii DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Chile, the United Nations, the Nippon Foundation of Japan or Dalhousie University. iii iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my profound gratitude to the Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), Office of Legal Affairs, United Nations, and the Nippon Foundation of Japan for making this extraordinary and rewarding experience possible. I want to extend my deepest gratitude to the Marine and Environmental Law Institute of Dalhousie University, Canada, and the Sir James Dunn Law Library at the same University Law School, for the assistance, support and warm hospitality provided in the first six months of my fellowship. My special gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Aldo Chircop, for all his guidance and especially for encouraging me to broaden my perspective in order to understand the complexity of the area of research. I would also like to extend my appreciation to those persons who, with no interest but that of helping me through this process, provided me with new insights and perspectives: Jay Batongbacal (JSD Candidate, Dalhousie Law School, Dalhousie University), Johanne Fischer (Executive Secretary of NAFO), Robert Fournier (Marine Affairs Programme, Dalhousie University), Michael Shewchuck (DOALOS), André Tahindro (DOALOS), and David VanderZwaag (Dalhousie Law School, Dalhousie University). -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

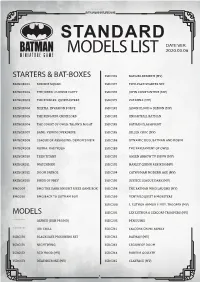

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263 -

The Ideology of Nolan's Batman Trilogy

MM The ideology of Nolan’s Batman trilogy Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy messed-up man behind the mask, had has been critically acclaimed and a a number of consequences for the supposedly ‘fun’ franchise. Leaving the huge success at the box office. Pete batsuit out of much of the trilogy and Turner evaluates its exploration setting it in a Gotham City so highly of dark themes, and considers recognisable that it might as well have been called New York, the director seems to have accusations of a reactionary been inviting critics to make comparisons ideology. between the films’ events and their contemporary socio-political context. Nolan stated in a Rolling Stone ‘You have to become an interview that ‘the films genuinely aren’t idea’ intended to be political’ but many have After Joel Schumacher’s Batman and argued otherwise, enforcing their own Robin was a day-glo disaster in 1997, interpretations on the ideas of the trilogy. anyone would think the director had killed Douthat (2012) even goes so far as to argue off comic book icon Batman for good. But that only eight years later, British director Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy is notable for being much more explicitly right-wing Christopher Nolan resurrected the dark than almost any Hollywood blockbuster of knight, losing the sidekick, neon lights recent memory. and rubber nipples in favour of enhanced Are these accusations fair or are there realism and contemporary relevance. some alternative interpretations of Batman’s Nolan’s focus on Bruce Wayne, the most recent reincarnation? english and media centre | April 2013 | MediaMagazine 37 MM Some find the moral murkiness of the films to be more about criticising America’s behaviour than celebrating what was achieved through morally dubious tactics. -

Narratives of Fear and the War on Terror in the Dark Knight Trilogy David A

Liberated Arts: A Journal for Undergraduate Research Volume 2, Issue 1 Article 1 2016 Do Some Men Just Want to Watch the World Burn? Narratives of Fear and the War on Terror in The Dark Knight Trilogy David A. Brooks Huron University College Follow this and additional works at: https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/lajur Recommended Citation Brooks, David A. (2016) "Do Some Men Just Want to Watch the World Burn? Narratives of Fear and the War on Terror in The Dark Knight Trilogy," Liberated Arts: a journal for undergraduate research: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 1. Liberated Arts is an open access journal, which means that its content is freely available without charge to readers and their institutions. All content published by Liberated Arts is licensed under the Creative Commons License, Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Readers are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without seeking prior permission from Liberated Arts or the authors. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Liberated Arts: A Journal for Undergraduate Research Brooks 1 Do Some Men Just Want to Watch the World Burn? Narratives of Fear and the War on Terror in The Dark Knight Trilogy David A. Brooks, Huron University College Abstract: The Dark Knight Trilogy, directed by Christopher Nolan, while at first glance a mere fantasy story about a costumed crime-fighter, hold a much deeper meaning as the films examine the government constructed War on Terror. -

Base Cards Film

BASE CARDS Red Deco Foil Variant #/80 Green Deco Foil Variant #/30 Silver Deco Foil Variant #/20 01 Return to the Throne 28 God vs. Man 02 Aquaman Arrives 29 God is Good as Dead 03 Wrath of the Seven Seas 30 Leave it to Her 04 Ocean Master 31 Zod’s Sentence 05 Land and Sea 32 Sending Kal-El Away 06 Face-Off 33 More than Human 07 Beacons of Hope 34 Symbol of Hope 08 Cold Feet 35 Evolution Always Wins 09 Fast Friends 36 First Kiss 10 Testing the Waters 37 Lucius’s New Toy 11 Confronting Steppenwolf 38 Darkness Falls 12 Demigoddess 39 Battle of Gotham 13 On the Front Line 40 Renegade 14 Leading the Charge 41 The Slow Knife 15 The Queen’s Command 42 Shoot to Kill 28 16 A Slow Boat to London 43 Smile 17 What’s a Secretary? 44 Watch the World Burn 18 No Man’s Land 45 Hero or Villain? 19 The Voice of God 46 The Joker’s Philosophy 20 Fitting Name 47 Leaving it to Chance 21 Courting a Madman 48 Gotham’s Hero 22 Pyrokinetic Homeboy 49 Ducard’s Tutelage 23 Negotiating Payment 50 Facing Fears 24 Playing the Part 51 The League of Shadows 25 Superman Stands Trial 52 The Tools of a Hero 26 Lexcorp Gala 53 True Identity 43 27 The Red Capes are Coming 54 Joining Forces FILM CEL Chase Cards (1:6 packs) FC1 Aquaman FC14 Batman v Superman: FC2 Aquaman Dawn of Justice FC3 Aquaman FC15 Batman v Superman: FC4 Justice League Dawn of Justice FC5 Justice League FC16 Man of Steel FC6 Justice League FC17 Man of Steel FC7 Wonder Woman FC18 Man of Steel FC8 Wonder Woman FC19 The Dark Knight Rises FC10 FC9 Wonder Woman FC20 The Dark Knight Rises FC10 Suicide Squad FC21 The Dark Knight Rises FC11 Suicide Squad FC22 The Dark Knight FC12 Suicide Squad FC23 The Dark Knight FC13 Batman v Superman: FC24 The Dark Knight Dawn of Justice FC25 Batman Begins FC26 Batman Begins FC14 All DC characters and elements © & TM DC Comics and Warner Bros. -

PRESS Graphic Designer

© 2021 MARVEL CAST Natasha Romanoff /Black Widow . SCARLETT JOHANSSON Yelena Belova . .FLORENCE PUGH Melina . RACHEL WEISZ Alexei . .DAVID HARBOUR Dreykov . .RAY WINSTONE Young Natasha . .EVER ANDERSON MARVEL STUDIOS Young Yelena . .VIOLET MCGRAW presents Mason . O-T FAGBENLE Secretary Ross . .WILLIAM HURT Antonia/Taskmaster . OLGA KURYLENKO Young Antonia . RYAN KIERA ARMSTRONG Lerato . .LIANI SAMUEL Oksana . .MICHELLE LEE Scientist Morocco 1 . .LEWIS YOUNG Scientist Morocco 2 . CC SMIFF Ingrid . NANNA BLONDELL Widows . SIMONA ZIVKOVSKA ERIN JAMESON SHAINA WEST YOLANDA LYNES Directed by . .CATE SHORTLAND CLAUDIA HEINZ Screenplay by . ERIC PEARSON FATOU BAH Story by . JAC SCHAEFFER JADE MA and NED BENSON JADE XU Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. LUCY JAYNE MURRAY Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO LUCY CORK Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO ENIKO FULOP Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM LAUREN OKADIGBO Executive Producer . .NIGEL GOSTELOW AURELIA AGEL Executive Producer . SCARLETT JOHANSSON ZHANE SAMUELS Co-Producer . BRIAN CHAPEK SHAWARAH BATTLES Co-Producer . MITCH BELL TABBY BOND Based on the MADELEINE NICHOLLS MARVEL COMICS YASMIN RILEY Director of Photography . .GABRIEL BERISTAIN, ASC FIONA GRIFFITHS Production Designer . CHARLES WOOD GEORGIA CURTIS Edited by . LEIGH FOLSOM BOYD, ACE SVETLANA CONSTANTINE MATTHEW SCHMIDT IONE BUTLER Costume Designer . JANY TEMIME AUBREY CLELAND Visual Eff ects Supervisor . GEOFFREY BAUMANN Ross Lieutenant . KURT YUE Music by . LORNE BALFE Ohio Agent . DOUG ROBSON Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Budapest Clerk . .ZOLTAN NAGY Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Man In BMW . .MARCEL DORIAN Second Unit Director . DARRIN PRESCOTT Mechanic . .LIRAN NATHAN Unit Production Manager . SIOBHAN LYONS Mechanic’s Wife . JUDIT VARGA-SZATHMARY First Assistant Director/ Mechanic’s Child . .NOEL KRISZTIAN KOZAK Associate Producer . -

Governor Takes 'Emergency' Hiring Action for SC Prisons

TSA’s Cookey-Gam to play volleyball with USC Aiken B1 TUESDAY, APRIL 24, 2018 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents Governor takes ‘emergency’ hiring action for S.C. prisons PHOTOS BY MICAH GREEN / THE SUMTER ITEM Chuck Costner has been shearing sheep at Old McCaskill’s Farm for 20 years. His work led to the opening BY MEG KINNARD in Bishopville, about 40 miles of the farm each spring for people to watch. Right: his wife, Candy, holds one sheep’s worth of wool. Associated Press east of Columbia. One by one, Stirling said three dorms at the maximum-security COLUMBIA — South Car- prison erupted into fights, Have you any wool? olina's governor announced communication aided by in- Monday he's taking "emer- mates with cellphones. gency" action in hopes of Once officers were finally making state prisons safer able to regain control, seven Sheep shearer sheds light on following last week’s deadly inmates lay dead, slashed rioting. with homemade knives and Gov. Henry McMaster is- beaten. Twenty-two others sued an executive order were injured. State police are daily farm life at Old McCaskill’s waiving state procurement still investigating the deaths, regulations and the Cor- BY KAYLA ROBINS and professional sheep shear- for hiring by rections De- [email protected] er, has been making the trip to the Depart- ‘We believe this partment has Old McCaskill’s Farm each ment of Cor- asked an out- spring for the last 20 years to rections. De- executive order gives side group to He has been shearing sheep alleviate the family’s about 30 claring an do a thorough since 1986 (for the public.