Celtic Legacy in Galicia Manuel Alberro University of Uppsala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unity in Diversity, Volume 2

Unity in Diversity, Volume 2 Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept Edited by Sabine Asmus and Barbara Braid Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept Edited by Sabine Asmus and Barbara Braid This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Sabine Asmus, Barbara Braid and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5700-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5700-0 CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................. vii Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept of Unity in Diversity Sabine Asmus Part I: Cultural Markers Chapter One ................................................................................................ 3 Questions of Identity in Contemporary Ireland and Spain Cormac Anderson Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 27 Scottish Whisky Revisited Uwe Zagratzki Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 39 Welsh -

Exam Sample Question

Latin II St. Charles Preparatory School Sample Second Semester Examination Questions PART I Background and History (Questions 1-35) Directions: On the answer sheet cover the letter of the response which correctly completes each statement about Caesar or his armies. 1. The commander-in-chief of a Roman army who had won a significant victory was known as a. dux b. imperator c. signifer d. sagittarius e. legatus 2. Caesar was consul for the first time in the year a. 65 B.C. b. 70 B.C. c. 59 B.C. d. 44 B.C. e. 51 B.C. PART II Vocabulary (Questions 36-85) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the correct meaning for the boldfaced Latin word in the left band column. 36. doctus a. edge b. entrance c. learned d. record e. friendly 37. incipio a. stop b. speaker c. rest d. happen e. begin PART III Prepared Translation, Passage A (Questions 86-95) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the best translation for each Latin sentence or fragment. 86. Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres. a. The Gauls divided themselves into three parts b. All of Gaul was divided into three parts c. Three parts of Gaul have been divided d. Everyone in Gaul was divided into three parts PART IV Prepared Translation, Passage B (Questions 96-105) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the best translation for each Latin sentence or fragment. 96. Galli se Celtas appellant. Romani autem eos Gallos appellant. -

El Oppidum De Badajoz. Ocupaciones Prehistoricas En La Alcazaba

e Complutum Extra, 4, 1994 EL OPPIDUM DE BADAJOZ. OCUPACIONES PREHISTORICAS EN LA ALCAZABA Luis Bermcal~Range1* RESUMEN.- El oppidumn de Badajoz, excavado desde 1977 hasta 1986, se encuentra bajo las fortificaciones de la ciudad medieval y moderna. La importancia de este sitio comenzó hacia el III milenio a. C.. conviniéndose durante el Bronce Atlántico y la Edad del Hierro en un importante asentamiento de las Vegas del Guadiana. Las excavaciones realizadas muestran la importancia de este oppidum como centro de poder local durante el Periodo Orientalizante, vinculado con Tartessos y las vías de comunicación con las zonas Mediterráneas. Después del siglo Va. C. aparecieron nuevos elementos relacionados con los pueblos célticos que documentan lasfuentes clósicas en el Suroeste de la Península Ibérica. En conclusión, esta excavación muestra una de las mós completas secuencias estratigráficas, comparable a Medellín o Alcacer do Sal, fundamental para comprender el proceso cultural del? milenio a. C. hasta la conquista romana. ABSTRACT.- The oppidum of Badajoz, excavatedfrom 1977 tilí 1986, is placed under medieval and modern town fortiflcations. The importance of the place began at tite 3rd. milennium BC ant! it was renewed during tite Atlantic Bronze ant! ¡ron Age as an important seulement of the Guadiana basin. Tite excavations flnds show the imponance of tite oppidum of Badajoz as a center of local power during tite Orientalizing Periott related tu Tartessos ant! the comunication ways with Mediterranean areas <Phoenicians ant! also Greeks). After the Sth century BC some elements appeared related tu Celtic peoples docwnented by Classical soarces in tite Southwestern of Iberia. In conclusion, tite excavation of tite oppidum 6]’ Badajoz give one of the most complete strattfied sequence, comparable witit Medellín ant! Alcácer do Sal, and specially important from the unt!erstanding oftite cultural process oftite lrst. -

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

Celts and the Castro Culture in the Iberian Peninsula – Issues of National Identity and Proto-Celtic Substratum

Brathair 18 (1), 2018 ISSN 1519-9053 Celts and the Castro Culture in the Iberian Peninsula – issues of national identity and Proto-Celtic substratum Silvana Trombetta1 Laboratory of Provincial Roman Archeology (MAE/USP) [email protected] Received: 03/29/2018 Approved: 04/30/2018 Abstract : The object of this article is to discuss the presence of the Castro Culture and of Celtic people on the Iberian Peninsula. Currently there are two sides to this debate. On one hand, some consider the “Castro” people as one of the Celtic groups that inhabited this part of Europe, and see their peculiarity as a historically designed trait due to issues of national identity. On the other hand, there are archeologists who – despite not ignoring entirely the usage of the Castro culture for the affirmation of national identity during the nineteenth century (particularly in Portugal) – saw distinctive characteristics in the Northwest of Portugal and Spain which go beyond the use of the past for political reasons. We will examine these questions aiming to decide if there is a common Proto-Celtic substrate, and possible singularities in the Castro Culture. Keywords : Celts, Castro Culture, national identity, Proto-Celtic substrate http://ppg.revistas.uema.br/index.php/brathair 39 Brathair 18 (1), 2018 ISSN 1519-9053 There is marked controversy in the use of the term Celt and the matter of the presence of these people in Europe, especially in Spain. This controversy involves nationalism, debates on the possible existence of invading hordes (populations that would bring with them elements of the Urnfield, Hallstatt, and La Tène cultures), and the possible presence of a Proto-Celtic cultural substrate common to several areas of the Old Continent. -

The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/Yalebooks.Com Now Available in Paperback Recent & Classic Titles

2017 The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/yalebooks.com Now available in paperback Recent & Classic Titles & Pax Romana Augustus War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World First Emperor of Rome ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY Renowned scholar Adrian Goldsworthy Caesar Augustus’ story, one of the most turns to the Pax Romana, a rare period riveting in western history, is filled with when the Roman Empire was at peace. A drama and contradiction, risky gambles vivid exploration of nearly two centuries and unexpected success. This biography of Roman history, Pax Romana recounts captures the real man behind the crafted real stories of aggressive conquerors, image, his era, and his influence over two failed rebellions, and unlikely alliances. millennia. “An excellent book. First-rate.” Paper 2015 640 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps —Richard A. Gabriel, Military History 978-0-300-21666-0 $20.00 Paper 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. Cloth 2014 624 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps 978-0-300-23062-8 $22.00 978-0-300-17872-2 $35.00 Hardcover 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. 978-0-300-17882-1 $32.50 Caesar Life of a Colossus Recent & Classic Titles ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY This major new biography by a distin- guished British historian offers a remark- In the Name of Rome ably comprehensive portrait of a leader The Men Who Won the Roman Empire whose actions changed the course of ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY; WITH A NEW PREFACE Western history and resonate some two A world-renowned authority offers a thousand years later. -

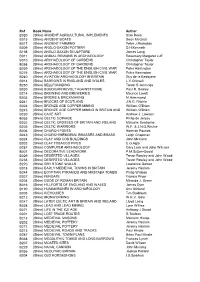

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Manx Gaelic and Physics, a Personal Journey, by Brian Stowell

keynote address Editors’ note: This is the text of a keynote address delivered at the 2011 NAACLT conference held in Douglas on The Isle of Man. Manx Gaelic and physics, a personal journey Brian Stowell. Doolish, Mee Boaldyn 2011 At the age of sixteen at the beginning of 1953, I became very much aware of the Manx language, Manx Gaelic, and the desperate situation it was in then. I was born of Manx parents and brought up in Douglas in the Isle of Man, but, like most other Manx people then, I was only dimly aware that we had our own language. All that changed when, on New Year’s Day 1953, I picked up a Manx newspaper that was in the house and read an article about Douglas Fargher. He was expressing a passionate view that the Manx language had to be saved – he couldn’t understand how Manx people were so dismissive of their own language and ignorant about it. This article had a dra- matic effect on me – I can say it changed my life. I knew straight off somehow that I had to learn Manx. In 1953, I was a pupil at Douglas High School for Boys, with just over two years to go before I possibly left school and went to England to go to uni- versity. There was no university in the Isle of Man - there still isn’t, although things are progressing in that direction now. Amazingly, up until 1992, there 111 JCLL 2010/2011 Stowell was no formal, official teaching of Manx in schools in the Isle of Man. -

Bronze Objects for Atlantic Elites in France (13Th-8Th Century BC) Pierre-Yves Milcent

Bronze objects for Atlantic Elites in France (13th-8th century BC) Pierre-Yves Milcent To cite this version: Pierre-Yves Milcent. Bronze objects for Atlantic Elites in France (13th-8th century BC). Hunter Fraser; Ralston Ian. Scotland in Later Prehistoric Europe, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, pp.19-46, 2015, 978-1-90833-206-6. hal-01979057 HAL Id: hal-01979057 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01979057 Submitted on 12 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. FROM CHAINS TO BROOCHES Scotland in Later Prehistoric Europe Edited by FRASER HUNTER and IAN RALSTON iii SCOTLAND IN LATER PREHISTORIC EUROPE Jacket photography by Neil Mclean; © Trustees of National Museums Scotland Published in 2015 in Great Britain by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Society of Antiquaries of Scotland National Museum of Scotland Chambers Street Edinburgh EH1 1JF Tel: 0131 247 4115 Fax: 0131 247 4163 Email: [email protected] Website: www.socantscot.org The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland is a registered Scottish charity No SC010440. ISBN 978 1 90833 206 6 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Haplogroup R1b (Y-DNA)

Eupedia Home > Genetics > Haplogroups (home) > Haplogroup R1b Haplogroup R1b (Y-DNA) Content 1. Geographic distribution Author: Maciamo. Original article posted on Eupedia. 2. Subclades Last update January 2014 (revised history, added lactase 3. Origins & History persistence, pigmentation and mtDNA correspondence) Paleolithic origins Neolithic cattle herders The Pontic-Caspian Steppe & the Indo-Europeans The Maykop culture, the R1b link to the steppe ? R1b migration map The Siberian & Central Asian branch The European & Middle Eastern branch The conquest of "Old Europe" The conquest of Western Europe IE invasion vs acculturation The Atlantic Celtic branch (L21) The Gascon-Iberian branch (DF27) The Italo-Celtic branch (S28/U152) The Germanic branch (S21/U106) How did R1b become dominant ? The Balkanic & Anatolian branch (L23) The upheavals ca 1200 BCE The Levantine & African branch (V88) Other migrations of R1b 4. Lactase persistence and R1b cattle pastoralists 5. R1 populations & light pigmentation 6. MtDNA correspondence 7. Famous R1b individuals Geographic distribution Distribution of haplogroup R1b in Europe 1/22 R1b is the most common haplogroup in Western Europe, reaching over 80% of the population in Ireland, the Scottish Highlands, western Wales, the Atlantic fringe of France, the Basque country and Catalonia. It is also common in Anatolia and around the Caucasus, in parts of Russia and in Central and South Asia. Besides the Atlantic and North Sea coast of Europe, hotspots include the Po valley in north-central Italy (over 70%), Armenia (35%), the Bashkirs of the Urals region of Russia (50%), Turkmenistan (over 35%), the Hazara people of Afghanistan (35%), the Uyghurs of North-West China (20%) and the Newars of Nepal (11%). -

CV-Ligia María Castro Monge (EN-Julio2017-RIM)

LIGIA MARIA CASTRO-MONGE [email protected] [email protected] Telephone: (506) 8314-3313 Skype: lcastromonge San José, Costa Rica COMPETENCIES Prominent experience in the economic and financial fields, both at the academic and practical levels. In the financial field, the specialization areas are financial institutions’ regulation, risk analysis and microfinance. Excellent capacity for leadership, decision-making and teamwork promotion. Oriented towards results, innovative and with excellent interpersonal relationships. EXPERIENCE: CONSULTING May-Sept 17 The SEEP Network U.S.A. Awareness raising & dissemination of best practices for disaster risk reduction among FSPs, their clients and relevant stakeholders • To develop, pilot and finalize workshop methodology designed to raise awareness and disseminate existing best practices related to disaster risk reduction for FSPs, their clients and other relevant stakeholders working in disaster and crisis-affected environments. • Pilot projects to be conducted in Nepal (July 2017) and the Philippines (August 2017) Jan-Sept 17 BAYAN ADVISERS Jordan Establishment of a full-function risk management unit for Vitas-Jordan • Diagnostic analysis and evaluation phase applying the RMGM to define an institutional road map for strengthening the risk management framework and function including, among others, a high-level risk management department structure and the establishment of a risk committee at the board level • Based on the institutional road map to strengthen risk management, development -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as