Representing Transmedia Fictional Worlds Through Ontology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1 Free

FREE DAREDEVIL: ULTIMATE COLLECTION VOLUME 1 PDF Ed Brubaker,Michael Lark,David Aja | 304 pages | 08 Feb 2012 | Marvel Comics | 9780785163343 | English | New York, United States Softcover Daredevil No Collectible Graphic Novels & TPBs for sale | eBay Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1 Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. David W. Mack Illustrator. Alex Maleev Illustrator. During a character-defining run, Brian Michael Bendis crafted a pulp-fiction narrative that exploited the Man Without Fear's rich tapestry of Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1 and psychodrama, and resolved them in an incredibly nuanced, modern approach. Now, this Eisner Award-winning run is collected across three titanic trade paperbacks In this volume, witness the Kingpin's downfall at the hand During a character-defining run, Brian Michael Bendis crafted a Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1 narrative that exploited the Man Without Fear's rich tapestry of characters and psychodrama, and resolved them in an incredibly nuanced, modern approach. Now, this Eisner Award- winning run is collected across three titanic trade paperbacks In this volume, witness the Kingpin's downfall at the hands of Sammy Silke and see how a down-on-his-luck FBI agent can change Matt's life forever. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Other Editions 2. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 the Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions Committee: Adam Z. Newton, Co-Supervisor John M. Slatin, Co-Supervisor Brian A. Bremen David J. Phillips Clay Spinuzzi Margaret A. Syverson Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions by Jason Todd Craft, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2004 Dedication For my family Acknowledgements Many thanks to my dissertation supervisors, Dr. Adam Zachary Newton and Dr. John Slatin; to Dr. Margaret Syverson, who has supported this work from its earliest stages; and, to Dr. Brian Bremen, Dr. David Phillips, and Dr. Clay Spinuzzi, all of whom have actively engaged with this dissertation in progress, and have given me immensely helpful feedback. This dissertation has benefited from the attention and feedback of many generous readers, including David Barndollar, Victoria Davis, Aimee Kendall, Eric Lupfer, and Doug Norman. Thanks also to Ben Armintor, Kari Banta, Sarah Paetsch, Michael Smith, Kevin Thomas, Matthew Tucker and many others for productive conversations about branding and marketing, comics universes, popular entertainment, and persistent world gaming. Some of my most useful, and most entertaining, discussions about the subject matter in this dissertation have been with my brother, Adam Craft. I also want to thank my parents, Donna Cox and John Craft, and my partner, Michael Craigue, for their help and support. -

Theorising the Practice of Expressing a Fictional World Across Distinct Media and Environments

Transmedia Practice: Theorising the Practice of Expressing a Fictional World across Distinct Media and Environments by Christy Dena A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) School of Letters, Art and Media Department of Media and Communications Digital Cultures Program University of Sydney Australia Supervisor: Professor Gerard Goggin Associate Supervisor: Dr. Chris Chesher Associate Supervisor: Dr. Anne Dunn 2009 Let’s study, with objectivity and curiosity, the mutation phenomenon of forms and values in the current world. Let’s be conscious of the fact that although tomorrow’s world does not have any chance to become more fair than any other, it owns a chance that is linked to the destiny of the current art [...] that of embodying, in their works some forms of new beauty, which will be able to arise only from the meet of all the techniques. (Francastel 1956, 274) Translation by Regina Célia Pinto, emailed to the empyre mailing list, Jan 2, 2004. Reprinted with permission. To the memory of my dear, dear, mum, Hilary. Thank you, for never denying yourself the right to Be. ~ Transmedia Practice ~ Abstract In the past few years there have been a number of theories emerge in media, film, television, narrative and game studies that detail the rise of what has been variously described as transmedia, cross-media and distributed phenomena. Fundamentally, the phenomenon involves the employment of multiple media platforms for expressing a fictional world. To date, theorists have focused on this phenomenon in mass entertainment, independent arts or gaming; and so, consequently the global, transartistic and transhistorical nature of the phenomenon has remained somewhat unrecognised. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

The Only Way Is Down: Lark and Brubaker's Saga As '70S Cinematic

The Only Way is Down: Lark and Brubaker’s Saga as ’70s Cinematic Noir an Essay by Ryan K Lindsay from THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: EXAMINING MATT MURDOCK AND DAREDEVIL THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: EXAMINING MATT MURDOCK AND DAREDEVIL EDITED BY RYAN K. LINDSAY SEQUART RESEARCH & LITERACY ORGANIZATION EDWARDSVILLE, ILLINOIS The Devil is in the Details: Examining Matt Murdock and Daredevil Edited by Ryan K. Lindsay Copyright © 2013 by the respective authors. Daredevil and related characters are trademarks of Marvel Comics © 2013. First edition, February 2013, ISBN 978-0-5780-7373-6. All rights reserved. Except for brief excerpts used for review or scholarly purposes, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever, including electronic, without express consent of the publisher. Cover by Alice Lynch. Book design by Julian Darius. Interior art is © Marvel Comics; please visit marvel.com. Published by Sequart Research & Literacy Organization. Edited by Ryan K. Lindsay. Assistant edited by Hannah Means-Shannon. For more information about other titles in this series, visit sequart.org/books. The Only Way is Down: Lark and Brubaker’s Saga as ’70s Cinematic Noir by Ryan K Lindsay Cultural knowledge indicates that Daredevil is the noir character of the Marvel Universe. This assumption is an unchallenged perception that doesn’t actually hold much water under any major scrutiny. If you add up all of Daredevil’s issues to date, the vast majority are not “noir.” Mild examination exposes Daredevil as one of the most diverse characters who has ever been written across a series of genres, from swashbuckling romance, to absurd space opera, to straight up super-heroism and, often, to crime saga. -

The Lawyer As Superhero: How Marvel Comics' Daredevil Depicts

Barry University School of Law Digital Commons @ Barry Law Faculty Scholarship Spring 5-2019 The Lawyer as Superhero: How Marvel Comics' Daredevil Depicts the American Court System and Legal Practice Louis Michael Rosen Barry University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/facultyscholarship Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation 47 Capital U. L. Rev. 379 (2019) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Barry Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Barry Law. THE LAWYER AS SUPERHERO: HOW MARVEL COMICS’ DAREDEVIL DEPICTS THE AMERICAN COURT SYSTEM AND LEGAL PRACTICE LOUIS MICHAEL ROSEN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 380 II. BACKGROUND: POPULAR CULTURE AND THE LAW THEORIES ....... 387 III. DAREDEVIL––THE STORY SO FAR ............................................... 391 A. Daredevil in the Sights of Frank Miller ....................................... 391 B. Daredevil Through the Eyes of Brian Michael Bendis ................ 395 C. Daredevil’s Journey to Redemption by David Hine .................... 402 D. Daredevil Goes Public, by Mark Waid ........................................ 406 IV. DAREDEVIL’S FRESH START AND BIGGEST CASE EVER, BY CHARLES SOULE ...................................................................................... 417 V. CONCLUSION .................................................................................... 430 Copyright © 2019, Louis Michael Rosen. * Louis Michael Rosen is a Reference Librarian and Associate Professor of Law Library at Barry University School of Law in Orlando, Florida. He would like to thank Professor Taylor Simpson-Wood, his mentor, ally, advocate, cheerleader, and ever-patient editor as he wrote this article. -

The Sense of a Beginning

THE SENSE OF A BEGINNING: THEORY OF THE LITERARY OPENING A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Niels Buch Leander January 2012 © 2012 Niels Buch Leander THE SENSE OF A BEGINNING: THEORY OF THE LITERARY OPENING Niels Buch Leander, Ph.D. Cornell University 2012 This dissertation is the first comprehensive study in English of the literary opening and its impact on modern literary criticism. It thus fills an astounding gap in Anglo-American criticism, which has neglected openings and instead focused on endings, as exemplified by Frank Kermode‘s The Sense of an Ending (1967). Through a study of the constant formal challenges of novelistic openings, primarily during modernism, this dissertation illustrates the significance of the opening in literary creation and in literary criticism. Chapter 1 analyses how openings attempt to lend authority from natural beginnings as well as from cosmologies, which leads to the conclusion that the beginning of a story is also a story of the beginning. Chapter 2 examines literary openings more closely from a formal and narrative point of view, thereby outlining a theory of openings based on linguistic considerations such as pragmatic conventions and cooperative rules. The chapter establishes a taxonomy of openings based on five ―signals‖ of the opening. In particular, the chapter develops the concept of ―perspectival abruptness‖, which is to be differentiated from the temporal abruptness known as in medias res. ―Perspectival abruptness‖ is presented as a tool for the critic and the literary historian to understand the particular nature of modern fiction. -

How Do Readers Understand Character Identities

How do readers understand the different ways that characters behave when they appear in both the text and paratext of the same comic? Mark Hibbett, PhD student at University of the Arts London. Comics characters have a long history of being used for advertising purposes, perhaps most famously in the long-running series of advertisements for Hostess fruit pies, in which superheroes thwart evildoers through judicious use of processed confectionaries. A great example of this appears in "Fury Unleashed," a strip which appeared in Marvel comics dated April 1982. In it, Captain America realizes that neither his shield nor his superhuman strength can save Nick Fury, so instead throws Hostess fruit pies at his friend's captor, distracting him long enough for the heroes to escape. However, when Cap faces a similar scenario in Captain America #268, published that same month, he chooses to surrender himself to save his friends rather than simply providing a dessert option for his enemies. How are readers of Captain America #268 meant to understand what is going on? Are they expected to view these two versions of Captain America as different characters who just happen to look the same, or is something else going on? Another example of this tension between text and advertisement paratext appears in Fantastic Four #200, a double-length issue featuring a duel to the death between Mr Fantastic and Doctor Doom, with a center-spread advertisement in which Doom implores his own fans to enter a competition run by a candy company to ensure that fans of superheroes don't win instead. -

Realistic Fantasy Or Fantastic Realism: on Defining the Genre in Susanna Clarke´S Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell

Carl-William Ersgård Supervisor: Eivor Lindstedt EngK01 6 Januari 2010 Realistic Fantasy or Fantastic Realism: On Defining the Genre in Susanna Clarke´s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. Table of contents: 1. Introduction 1 2. Mirroring the world – Realism 2 3. Summoning the otherworld – Fantasy 9 4. Beyond reality – Fantasy and mimesis 15 5. Conclusion 18 6. Works Cited 20 Ersgård 1 Introduction: ”He hardly ever spoke of magic, and when he did it was like a history lesson and no one could bear to listen to him.” (1) With these, the first words of her novel Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell (2006), Susanna Clarke might as well have been describing the entirety of her work, not only one of its protagonists. The character described is Mr Gilbert Norrell, the first practical magician in England for centuries. He is one of a pair of magicians working side by side, and against each other, in the novel. The other, Mr Jonathan Strange, is Norrell´s opposite in every possible way. Where Norrell thinks all magic should be learnt from century-old-books, Jonathan Strange wants to experiment; where Norrell finds fairy-magic appalling and quite detestable, Jonathan Strange sees it as intriguing; and, perhaps most importantly, where Norrell wants to destroy all traces of the Raven King, the great magician- king of northern England, ever having existed, Jonathan Strange secretly houses a want to bring him back from the otherworld of Faerie. The quote above, together with the duality of the two main characters, create an excellent symbol for the whole novel. Whether or not the reader can “bear to listen” to Susanna Clarke´s narrative is, of course, a completely different question. -

PDF Download Green Owl Vol. 2 : Friends and Enemies

GREEN OWL VOL. 2 : FRIENDS AND ENEMIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brian M Osbourn | 110 pages | 02 Jan 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781505924183 | English | none Green Owl Vol. 2 : Friends and Enemies PDF Book Some of them collected together and became vortexes of barely containable power, creating inter-dimensional gateways. Bor Burison. Doctor Who Magazine , Venom: Separation Anxiety 2 , Wally comments, however, that they would be better as friends than enemies. Incredible Hulk , He quickly realizes that Mjolnir has vanished, and fears the otherworldly lightning had an effect on his hammer. X-Men 17 , This wiki All wikis. Crimson Dynamo I. The lightning effect throws energy all around and stuns Thor himself. Inklings welcomes and encourages signed lettersto-the- editor. Back on Earth, Captain America is fighting Bane. Captain Marvel. Categories :. The recent earthquake that took place in California offered us insight as to what would happen to the U. Disney's Aladdin 7 , Which ironically shows, winning a Pulitzer is easier than passing a political satire through Apple. Multiple studies done throughout the years have proven the effects of smoking to be harmful. But they have learned the futility of facing each other in a head-to-head struggle. Wolverine Vol 2 90 , English indie group wraps-up successful Humbug Tour in U. Paul Neary Josef Rubinstein. Savage Sword of Conan , The Lady Bulldogs were able to defeat all three teams. It is the novelty of the experience that makes it worthwhile. Moon Knight. Marvel Comics Presents , Nightmare 3 , Elektra 2 , They were called "Brothers", although they were also sisters, sexless, and everything in between. -

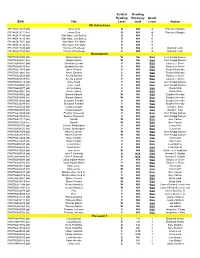

Dk Education Readinglevels Gui

Guided Reading Reading Recovery Grade ISBN Title Level level Level Author DK Adventures 9781465417237 (pb) Horse Club Q N/A 4 Patricia J Murphy 9781465418111 (hc) Horse Club Q N/A 4 Patricia J Murphy 9781465417244 (pb) Star Wars: Jedi Battles U N/A 5 9781465418135 (hc) Star Wars: Jedi Battles U N/A 5 9781465417251 (pb) Star Wars: Sith Wars U N/A 5 9781465418142 (hc) Star Wars: Sith Wars U N/A 5 9781465417220 (pb) Terrors of the Deep S N/A 4 Deborah Lock 9781465418128 (hc) Terrors of the Deep S N/A 4 Deborah Lock Biographies 9780756652098 (pb) Abigail Adams W NA 5&6 Kem Knapp Sawyer 9780756652081 (hc) Abigail Adams W NA 5&6 Kem Knapp Sawyer 9780756608347 (pb) Abraham Lincoln V N/A 5&6 Tanya Lee Stone 9780756608330 (hc) Abraham Lincoln V N/A 5&6 Tanya Lee Stone 9780756612470 (pb) Albert Einstein V N/A 5&6 Frieda Wishinsky 9780756612481 (hc) Albert Einstein V N/A 5&6 Frieda Wishinsky 9780756625528 (pb) Amelia Earhart V N/A 5&6 Tanya Lee Stone 9780756625535 (hc) Amelia Earhart V N/A 5&6 Tanya Lee Stone 9780756603410 (pb) Anne Frank V N/A 5&6 Kem Knapp Sawyer 9780756604905 (hc) Anne Frank V N/A 5&6 Kem Knapp Sawyer 9780756629977 (pb) Annie Oakley V N/A 5&6 Chuck Wills 9780756629861 (hc) Annie Oakley V N/A 5&6 Chuck Wills 9780756658052 (pb) Barack Obama W NA 5&6 Stephen Krensky 9780756658045 (hc) Barack Obama W NA 5&6 Stephen Krensky 9780756635282 (pb) Benjamin Franklin V N/A 5&6 Stephen Krensky 9780756635299 (hc) Benjamin Franklin V N/A 5&6 Stephen Krensky 9780756625542 (pb) Charles Darwin W N/A 5&6 David C.