Confidential Report of Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Schools in Alabama Within a 250 Mile Radius of Middle Tennessee State University

High Schools in Alabama within a 250 mile radius of Middle Tennessee State University CEEB High School Name City Zip Code CEEB High School Name City Zip Code 010395 A H Parker High School Birmingham 35204 012560 B B Comer Memorial School Sylacauga 35150 012001 Abundant Life School Northport 35476 012051 Ballard Christian School Auburn 36830 012751 Acts Academy Valley 36854 012050 Beauregard High School Opelika 36804 010010 Addison High School Addison 35540 012343 Belgreen High School Russellville 35653 010017 Akron High School Akron 35441 010035 Benjamin Russell High School Alexander City 35010 011869 Alabama Christian Academy Montgomery 36109 010300 Berry High School Berry 35546 012579 Alabama School For The Blind Talladega 35161 010306 Bessemer Academy Bessemer 35022 012581 Alabama School For The Deaf Talladega 35161 010784 Beth Haven Christian Academy Crossville 35962 010326 Alabama School Of Fine Arts Birmingham 35203 011389 Bethel Baptist School Hartselle 35640 010418 Alabama Youth Ser Chlkvlle Cam Birmingham 35220 012428 Bethel Church School Selma 36701 012510 Albert P Brewer High School Somerville 35670 011503 Bethlehem Baptist Church Sch Hazel Green 35750 010025 Albertville High School Albertville 35950 010445 Beulah High School Valley 36854 010055 Alexandria High School Alexandria 36250 010630 Bibb County High School Centreville 35042 010060 Aliceville High School Aliceville 35442 012114 Bible Methodist Christian Sch Pell City 35125 012625 Amelia L Johnson High School Thomaston 36783 012204 Bible Missionary Academy Pleasant 35127 -

North Alabama Regional ~ Results

North Alabama Regional ~ Results Division Rank Team NHSCC BID Junior High - Non Tumble 1 Richland JH School Small Varsity - Non Tumble 1 Greenbrier High School 2 Forrest High School Large Varsity - Non Tumble 1 Central Magnet School X Medium Varsity - Non Tumble 1 Richland High School X 2 Russell Co High School Large Varsity Coed - Non Tumble 1 Creek Wood High School Game Day Varsity - Non-Tumble 1 Spain Park High School X 2 Middle Tenn Christian High School X 3 Eufaula High School X 4 West Blocton High School X 4 Forrest High School X 5 Jasper High School 6 D.A.R. High School 7 Creek Wood High School 8 Silverdale Baptist Academy Small Varsity 1 Hazel Green High School X 2 Hueytown High School X 3 Columbia Academy X 4 Albertville High School 5 Oneonta High School Game Day Small/Medium Varsity 1 Wilson Central High School X 2 Sardis High School X 3 Randolph High School X 4 Greenbrier High School X 5 Bibb County High School 6 Lipscomb Academy Medium Varsity 1 Bob Jones High School X 2 Oakland High School X 3 Wilson Central High School X 4 Page High School X 5 Brooks High School X 6 Father Ryan High School X Super Varsity 1 James Clemens High School X 2 Spain Park High School X 3 Christ Presbyterian Academy Large Varsity 1 Buckhorn High School X 2 Scottsboro High School X 3 Arab High School X Game Day Large/Super Varsity 1 Buckhorn High School X 2 Wilson High School X 3 Arab High School X 4 Hueytown High School X 5 Dickson County High School X North Alabama Regional ~ Results Division Rank Team NHSCC BID Youth Recreation 1 Wilco Wildcats -

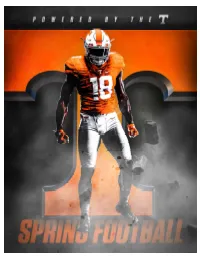

2018 SPRING GUIDE the BASICS Location (Founded): Knoxville, Tenn

2018 SPRING GUIDE THE BASICS Location (Founded): Knoxville, Tenn. (1794) Conference: Southeastern (SEC) Enrollment: 28,321 Colors: Orange & White Nickname: Volunteers Mascot: Smokey X (a Bluetick Coonhound) Band: Pride of the Southland President: Dr. Joe DiPietro Chancellor: Dr. Beverly J. Davenport Faculty Representative: Dr. Donald Bruce Director of Athletics: Phillip Fulmer Athletic Dept. Phone: 865.974.1224 Athletic Dept. Phone: 865.656.1200 FACILITY INFORMATION Facility (Opened): Neyland Stadium (1921) Capacity: 102,455 (Fifth-largest in CFB) Surface: Tifway 419 Bermuda Hybrid Grass Record at Neyland Stadium: 463-128-17 (.775) HISTORY First Year of Football: 1891 All-Time Overall Record: 833-383-53 (.677) All-Time SEC Record: 334-207-19 (.613) SEC Championships: 13 (1998, 1997, 1990, 1989, 1985, 1969, 2018 SCHEDULE 1967, 1956, 1951, 1946, 1940, 1939, 1938) Date Opponent Site SEC Eastern Division Championships: 5 Sept. 1 vs. West Virginia Charlotte, N.C. (2007, 2004, 2001, 1998, 1997) SEC Championship Games: 5 Sept. 8 ETSU Knoxville, Tenn. National Championships: 6 Sept. 15 UTEP Knoxville, Tenn. (1998, 1967, 1951, 1950, 1940, 1938) Sept. 22 Florida* Knoxville, Tenn. BCS Titles: 1 (1998) Sept. 29 at Georgia* Athens, Ga. TEAM INFORMATION Oct. 13 at Auburn* Auburn, Ala. 2017 Overall Record: 4-8 Oct. 20 Alabama* Knoxville, Tenn. Home / Away / Neutral: 3-4 / 0-4 / 1-0 Oct. 27 at South Carolina* Columbia, S.C. SEC Record: 0-8 Nov. 3 Charlotte Knoxville, Tenn. Home / Away: 0-4 / 0-4 Starters Returning In 2018: 13 Nov. 10 Kentucky* Knoxville, Tenn. Nov. 17 Missouri* Knoxville, Tenn. COACHING STAFF Nov. 24 at Vanderbilt* Nashville, Tenn. -

Athletic Handbook for Student Athletes

ATHLETIC HANDBOOK for 20- STUDENT ATHLETES 21 Spain Park High School, Hoover High School, Berry Middle School, Bumpus Hoover City Middle School, Simmons Middle School Schools TABLE OF CONTENTS MISSION STATEMENT 3 SPORTSMANSHIP 3 ALABAMA HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC ELIGIBILITY 4 HOOVER CITY SCHOOLS ATHLETIC ELIGIBILITY 4 ATTENDANCE ELIGIBILITY 4-5 SCHOOL DISCIPLINE 5 AWARDS 5 INFORMATION FOR ATHLETES 5-7 DRUG SCREENING POLICY 8-13 ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS 14-18 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF ATHLETIC HANDBOOK & MEDIA RELEASE 19 2 HOOVER CITY SCHOOLS ATHLETIC HANDBOOK FOR STUDENT ATHLETES MISSION STATEMENT Our mission is to provide learning opportunities through educational athletics that will empower our student athletes to grow as lifelong learners. The Athletic Handbook will in no way supersede or replace policies set forth in the Hoover High School Student Handbook. SPORTSMANSHIP A policy statement from the National Federation of State High School Associations expresses the concept of sportsmanship as follows: “The ideals of good sportsmanship, ethical behavior, and integrity permeate our culture. The values of good citizenship and high behavioral standards apply equally to all activity disciplines. In perception and practice, good sportsmanship shall be defined as those qualities of behavior which are characterized by generosity and genuine concern for others. Further, awareness is expected of the impact of an individual’s influence on the behavior of others. Good sportsmanship is viewed as a concrete measure of the understanding and commitment to fair play, ethical behavior, and integrity.” One of the main goals of the athletic program is to teach the concept of sportsmanship. Good sportsmanship requires that everyone be treated with respect. -

2011 Alabama Football Media Guide

FOOTBALL 1 THIS IS ALABAMA CREDITS: The 2011 University of Alabama Football Media Guide was produced by the staff of the UA Athletics Media Relations Office. The publication was written and edited by Jeff Purinton, Josh Maxson, Doug Walker, Brent 2011 Schedule / Staff .................................................2 Hollingsworth and Buddy Overstreet. Photography by UA Athletics Director of Photography Kent Gidley and his Athletic Department Directory ............................3 student assistants. Special thanks to the Crimson Tide coaching staff, the UA Creative Services department for the Quick Facts ...................................................................3 cover and page designs, to the teams of the NFL for their photography assistance and the staff of the SEC office. Media Relations Personnel .....................................3 Copyright 2011 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama. “Roll Tide”, “Crimson Tide”, “Bama” and the Media Information ..................................................... 4 primary and secondary logos are registered trademarks of The University of Alabama. ON THE GRIDIRON 2011 ALABAMA COACHING STAFF TABLE OF TABLE 2011 Alabama Football Preview .....................6-13 Nick Saban ....................................................................................................................................................Head Coach 2011 Roster..............................................................14-15 (Kent State, 1973) 2011 Opponents ....................................................16-17 -

Mobile, Alabama

“Choosing Education as a Career” Seminar: Mobile, Alabama In an effort to recruit more racially/ethnically diverse candidates, the COE held a national diverse student recruitment seminar in Mobile, Alabama, on June 7 – 8, 2018, titled “Choosing Education as a Career.” Invitations were extended to middle and high school principals, counselors, and parents in schools across Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Arkansas, and Kentucky. Thirty-seven individuals from six states attended the seminar and learned from MSU COE personnel about admissions, multicultural leadership scholarships, and year-long internship opportunities. The goal was to form partnerships with schools to recruit middle and high school students from underrepresented groups to choose teaching as a career. Some of these schools are now exploring options for working with the MSU EPP. Follow-up will be conducted in the late fall 2018 / early spring 2019 to determine how many students from the schools represented may be choosing education as a career as a result of this effort. INVITATION To: Personalize before sending. From: David Hough, Dean, College of Education, Missouri State Univesity Date: January 12, 2018 / January 16 / January 17 / January 18 / etc. Re: Seminar on Choosing Education as a Career You are invited to attend a Seminar to learn how high school sophomores and juniors can begin planning for a career in education. The Seminar will begin with a reception at 5:00 p.m. followed by a dinner meeting at 6:00 p.m. on Thursday, June 7, 2018. On Friday, June 8, 2018, sessions will begin at 9:00 a.m. -

X‐Indicates Schools Not Participating in Football.

(x‐Indicates schools not participating in football.) Hoover High School 1,902.95 Sparkman High School 1,833.70 Baker High School 1,622.25 Murphy High School 1,601.00 Prattville High School 1,516.15 Bob Jones High School 1,491.35 Enterprise High School 1,482.50 Virgil Grissom High School 1,467.05 Auburn High School 1,445.95 Jeff Davis High School 1,442.60 Smiths Station High School 1,358.00 Vestavia Hills High School 1,355.25 Thompson High School 1,319.70 Mary G. Montgomery High School 1,316.60 Huntsville High School 1,296.70 Central High School, Phenix City 1,267.35 Pelham High School 1,259.30 R. E. Lee High School 1,258.65 Oak Mountain High School 1,258.05 Theodore High School 1,228.60 Alma Bryant High School 1,168.65 Foley High School 1,145.80 McGill‐Toolen High School 1,131.30 Spain Park High School 1,128.10 Tuscaloosa County High School 1,117.35 Gadsden City High School 1,085.65 W.P. Davidson High School 1,056.35 Mountain Brook High School 1,009.15 Shades Valley High School 1,006.15 Northview High School 1,002.35 Fairhope High School 994.80 Hewitt‐Trussville High School 991.00 Austin High School 976.75 Hazel Green High School 976.50 Clay‐Chalkville High School 965.55 Florence High School 960.30 Pell City High School 924.45 G. W. Carver High School, Montgomery 918.80 Opelika High School 910.55 Buckhorn High School 906.25 Northridge High School 901.25 Lee High School, Huntsville 885.85 Oxford High School 883.75 Stanhope Elmore High School 880.70 Hillcrest High School 875.40 Robertsdale High School 871.05 Mattie T. -

Superintendent Andy Craig

Case 2:14-cv-02176-MHH Document 21-4 Filed 01/15/16 Page 1 of 181 FILED 2016 Jan-15 PM 07:58 U.S. DISTRICT COURT N.D. OF ALABAMA Exhibit 4 Case 2:14-cv-02176-MHH Document 21-4 Filed 01/15/16 Page 2 of 181 Andy Craig 1 Page 1 Page 3 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 1 make objections and assign grounds at the time 2 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA 2 of the trial, or at the time said deposition is 3 SOUTHERN DIVISION 3 offered in evidence, or prior thereto. 4 4 IT IS FURTHER STIPULATED AND AGREED 5 CIVIL ACTION NO: 2:13-cv-2176-MHH 5 that notice of filing of the deposition by the 6 JURY DEMAND 6 Commissioner is waived. 7 7 8 ROBIN LITAKER, 8 9 Plaintiff, 9 10 vs. 10 11 HOOVER BOARD OF EDUCATION, 11 12 ANDY CRAIG, in his individual 12 13 and official capacity as 13 14 Superintendent, and CAROL BARBER, 14 15 in her individual and office capacity 15 16 as Assistant Superintendent, 16 17 Defendants. 17 18 18 19 DEPOSITION TESTIMONY OF: 19 20 ANDY CRAIG 20 21 JULY 29, 2015 21 22 10:00 A.M. 22 23 23 Page 2 Page 4 1 S T I P U L A T I O N S 1 I N D E X 2 IT IS STIPULATED AND AGREED by and 2 3 between the parties through their respective 3 EXAMINATION BY: PAGE NUMBER: 4 counsel that the deposition of ANDY CRAIG may be 4 Mr. -

Spain Park High School (As It Should Appear in the Official Records)

2008 No Child Left Behind–Blue Ribbon Schools Program U.S. Department of Education X Public Private Cover Sheet Type of School Elementary MIddle X High K-12 (Check all that apply) Charter Title I Magnet Choice Name of Principal Mr. William Eugene Broadway (Specify: Ms., Miss, Mrs., Dr., Mr., Other) (As it should appear in the official records) Official School Name Spain Park High School (As it should appear in the official records) School Mailing Address 4700 Jaguar Drive (If address is P.O. Box, also include street address.) Birmingham Alabama 35242-4678 City State Zip Code+4(9 digits total) County Shelby State School Code Number* 0010 Telephone (205) 439-1400 Fax (205) 439-1401 Web site/URL http://www.hoover.k12.al.us/sphs E-mail [email protected] I have reviewed the information in this application, including the eligibility requirements on page 3, and certify that to the best of my knowledge all information is accurate. Date Principal's Signature Name of Superintendent Mr. James Andrew Craig (Specify: Ms., Miss, Mrs., Dr., Mr., Other) District Name Hoover City Schools Tel. (205) 439-1000 I have reviewed the information in this application, including the eligibility requirements on page 3, and certify that to the best of my knowledge all information is accurate. Date (Superintendent’s Signature) Name of School Board President/Chairperson Mrs. Donna Cook Frazier (Specify: Ms., Miss, Mrs., Dr., Mr., Other) I have reviewed the information in this application, including the eligibility requirements on page 3, and certify that to the best of my knowledge all information is accurate. -

Alumni End 5,000-Mile Ride on Campus Diversity at Vanderbilt Is an Eight-Part Series Appearing in Every Monday and Friday Issue in September

INSIDE What’s it like to balance In the Bubble 2 marriage and Opinion 4 college life? Sports 6 THETHE VOICEVOICE OFOF VANDERBILTVANDERBILT SINCESINCE 18881888 Life 8 page 8 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2006 • 118 TH YEAR, NO. 49 Fun & Games 12 SPECIAL REPORT CHARITY Alumni end 5,000-mile ride on campus Diversity at Vanderbilt is an eight-part series appearing in every Monday and Friday issue in September. With this series, we are attempting to bring diversity to the forefront of campus discussion. The profi les are not meant to showcase one group over another but to demonstrate the depth of the Vanderbilt community. While the series will offi cially last for one month, it is meant to demonstrate The Hustler’s commitment to consistently represent the entire Vanderbilt community. Chancellor’s Scholarship opens doors for diversity Awards given to 25 new students annually. By Allison Malone EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Each year, the Chancellor’s Scholars Program awards full scholarships to 25 incoming students who have demonstrated a commitment to leadership, diversity, citizenship and scholarship. Th e Chancellor’s Scholarship has aff ected diversity at Vanderbilt by addressing stereotypes and reaching out to underrepresented communities. BRETT KAMINSKY / The Vanderbilt Hustler Austin Bauman visits with a young oncology patient during his trip to Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt on Thursday. “Th e biggest problem with diversifying the student population, Alums bike across America to raise money for cancer research. RALLY ACROSS AMERICA FINALE from my personal experience as a Vanderbilt student in the late By Allison Smith WHAT 1960s, when there were three ASST NEWS EDITOR Parthenon in Centennial Park starting at the Children’s Hospital here. -

2020-22 Reclassification

2020-22 Reclassification (x-Indicates schools not participating in football.) (xx-Indicates school does not participate in any sport.) Listed below are the 2020-2021; 2021-22 Average Daily Enrollment Numbers issued by the State Department of Education which classifies each member school of the Alabama High School Athletic Association. These numbers do not include Competitive Balance for applicable schools. You will find the area/region alignment for each class in each sport under the sports area/region alignment. CLASS 7A School Name Enrollment Hoover High School 2,126.15 Auburn High School 2,034.80 Baker High School 1,829.10 Sparkman High School 1,810.20 Dothan High School 1,733.15 Enterprise High School 1,611.85 James Clemens High School 1,603.05 Vestavia Hills High School 1,532.00 Thompson High School 1,525.90 Mary G. Montgomery High School 1,522.15 Grissom High School 1,437.35 Prattville High School 1,425.20 Huntsville High School 1,410.85 Bob Jones High School 1,386.00 Central High School, Phenix City 1,377.60 Smiths Station High School 1,365.00 Davidson High School 1,311.65 Fairhope High School 1,293.20 Alma Bryant High School 1,266.75 Tuscaloosa County High School 1,261.70 Spain Park High School 1,240.40 Albertville High School 1,222.95 Jeff Davis High School 1,192.65 Oak Mountain High School 1,191.35 Hewitt-Trussville High School 1,167.85 Austin High School 1,139.45 Daphne High School 1,109.75 Foley High School 1,074.25 Gadsden City High School 1,059.55 Florence High School 1,056.95 Murphy High School 1,049.10 Theodore High School 1,046.20 2020-22 Reclassification (x-Indicates schools not participating in football.) (xx-Indicates school does not participate in any sport.) Listed below are the 2020-2021; 2021-22 Average Daily Enrollment Numbers issued by the State Department of Education which classifies each member school of the Alabama High School Athletic Association. -

Ahsaa Nfhs Network Broadcast Log for Aug. 20-24

AHSAA NFHS NETWORK BROADCAST LOG FOR AUG. 20-24 Start Time Activity LEVEl Participant 1 Participant 2 PRODUCER URL AHSAA KICKOFF CLASSIC Aug 20, 2020 - 7:00 PM CDT Football Varsity Montgomery Catholic HS Pike Road AHSAA TV / WOTM TV http://www.nfhsnetwork.com/events/ahsaa/gam34aca72a98 OTHER GAMES Aug 20, 2020 - 7:00 PM CDT Football Varsity Alabama Christian Trinity Presbyterian Alabama Christian http://www.nfhsnetwork.com/events/alabama-christian-academy-montgomery-al/gam997485f5fb Aug 20, 2020 - 7:00 PM CDT Football Varsity Albertville Arab Albertville High School http://www.nfhsnetwork.com/events/albertville-high-school-albertville-al/gam22a55eeb12 Aug 20, 2020 - 6:55 PM CDT Football Varsity Carbon Hill Curry Curry High School http://www.nfhsnetwork.com/events/curry-high-school-jasper-al/gam27fe1165f9 Aug 20, 2020 - 6:00 PM CDT Football Varsity Clarke County Sweet Water Sweet Water High School http://www.nfhsnetwork.com/events/sweet-water-high-school-sweet-water-al/gam8ae0bd24be Aug 20, 2020 - 7:00 PM CDT Football Varsity Cullman Grissom Cullman High School http://www.nfhsnetwork.com/events/cullman-high-school-cullman-al/gam193b1f060b Aug 20, 2020 - 6:30 PM CDT Football Varsity Decatur Russellville Decatur High School http://www.nfhsnetwork.com/events/decatur-high-school-decatur-al/gam72e593e77e Aug 20, 2020 - 6:40 PM CDT Football Varsity Decatur Russellville Russellville High School http://www.nfhsnetwork.com/events/russellville-high-school-russellville-al/gamfdc3f064f7 Aug 20, 2020 - 6:45 PM CDT Football Varsity Fairhope Spanish Fort