The Creation of Velocity with RECOVERY on Freestyle by Mark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Olympic Trials Results

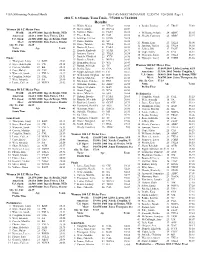

USA Swimming-National Meets Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 12:55 PM 1/26/2005 Page 1 2004 U. S. Olympic Team Trials - 7/7/2004 to 7/14/2004 Results 13 Walsh, Mason 19 VTAC 26.08 8 Benko, Lindsay 27 TROJ 55.69 Women 50 LC Meter Free 15 Silver, Emily 18 NOVA 26.09 World: 24.13W 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 16 Vollmer, Dana 16 FAST 26.12 9 Williams, Stefanie 24 ABSC 55.95 American: 24.63A 2000 Dara Torres, USA 17 Price, Keiko 25 CAL 26.16 10 Shealy, Courtney 26 ABSC 55.97 18 Jennings, Emilee 15 KING 26.18 U.S. Open: 24.50O 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 19 Radke, Katrina 33 SC 26.22 Meet: 24.90M 2000 Dara Torres, Stanfor 11 Phenix, Erin 23 TXLA 56.00 20 Stone, Tammie 28 TXLA 26.23 Oly. Tr. Cut: 26.39 12 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 56.02 21 Boutwell, Lacey 21 PASA 26.29 Name Age Team 13 Jeffrey, Rhi 17 FAST 56.09 22 Harada, Kimberly 23 STAR 26.33 Finals Time 14 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 56.11 23 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 26.34 15 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 56.19 24 Daniels, Elizabeth 22 JCCS 26.36 Finals 16 Nymeyer, Lacey 18 FORD 56.56 25 Boncher, Brooke 21 NOVA 26.42 1 Thompson, Jenny 31 BAD 25.02 26 Hernandez, Sarah 19 WA 26.43 2 Joyce, Kara Lynn 18 CW 25.11 27 Bastak, Ashleigh 22 TC 26.47 Women 100 LC Meter Free 3 Correia, Maritza 22 BA 25.15 28 Denby, Kara 18 CSA 26.50 World: 53.66W 2004 Libby Lenton, AUS 4 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 25.22 29 Ripple Johnston, Shell 23 ES 26.51 American: 53.99A 2002 Natalie Coughlin, U 5 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 25.27 29 Medendorp, Meghan 22 IST 26.51 U.S. -

OLYMPIC SWIMMING MEDAL STANDINGS Country Gold Silver Bronze Total

Speedo and are registered trademarks of and used under license from Speedo International trademarks of and used under license from Limited. registered are Speedo and CULLEN JONES RISE AND SWIM SPEED SOCKET GOGGLE SPEEDOUSA.COM ANTHONY ERVIN • 2000, 2012, 2016 OLYMPIAN discover your speed. new! EDGE COMFORTABLE, HIGH VELOCITY SWIM FINS To learn more, contact your local dealer or visit FINISinc.com STRENGTH DOES NOT COME FROM PHYSICAL CAPACITY. IT COMES FROM AN INDOMITABLE WILL. arenawaterinstinct.com SEPTEMBER 2016 FEATURES COACHING 010 ROCKIN’ IN RIO! 008 LESSONS WITH Winning half of the events and col- THE LEGENDS: lecting more than three times more SHERM CHAVOOR medals than any other country, Team by Michael J. Stott USA dominated the swimming compe- PUBLISHING, CIRCULATION tition at the XXXI Olympiad in Brazil. 040 Q&A WITH AND ACCOUNTING COACH www.SwimmingWorldMagazine.com 012 2016 RIO DE JANEIRO TREVOR MIELE Chairman of the Board, President - Richard Deal OLYMPICS: PHOTO by Michael J. Stott [email protected] GALLERY Publisher, CEO - Brent T. Rutemiller Photos by USA TODAY Sports 042 HOW THEY TRAIN [email protected] ELISE GIBBS Circulation/Art Director - Karen Deal 031 GIRLS’ NATIONAL by Michael J. Stott [email protected] HIGH SCHOOL Circulation/Operations Manager - Taylor Brien [email protected] CHAMPIONSHIPS: TRAINING THE NUMBERS Advertising Production Coordinator - Betsy Houlihan SPEAK FOR 039 DRYSIDE [email protected] THEMSELVES TRAINING: THE by Shoshanna Rutemiller NEED FOR SPEED EDITORIAL, PRODUCTION, The Carmel (Ind.) High School by J.R. Rosania MERCHANDISING, MARKETING AND girls’ swimming team just keeps ADVERTISING OFFICE on winning...and doing so with JUNIOR 2744 East Glenrosa Avenue, Phoenix, AZ 85016 class. -

Preparation of Sprint Swimmers

SWIMMING IN AUSTRALIA – November-December 2003 In this presentation I would like to share my PREPARATION OF experience in developing Michael Klim’s talent. Reflecting back on the 1998 World SPRINT SWIMMERS Championships and the way we approached the By Gennadi Touretski plan, I realise that since 1993 when I first met Presented at ASCTA 1998 Convention Michael I cannot recall a single occasion when he was significantly off track or disappointed in his progress. His motivation and dedication to INTRODUCTION training during this period was extremely high. Since this time, he has swum some 8,000km in The Men’s 100m Freestyle is regarded as the the pool with almost 500 races in his quest to blue riband event of the Olympic Swimming, become the number one swimmer in the world. World Championships, with many gold medallists becoming household names. It has Many people have asked me the key to lead to two Olympic champions to movie fame: Michael’s success. The answer is always the most notably Johnny Weissmuller in the role of same: natural talent coupled with the ability to Tarzan. He won two successive Olympic 100m work consistently and adopting a philosophy Freestyle gold medals in the 1920s. that you shouldn’t dive twice into the same water. The only way to win is with non-stop Among the Olympic champions we have two perfection. For developing athletes, the Australians … John Devitt and Michael Wenden personality of the swimmer is extremely who were successful in 1960 and 1968 important and swimming and training with respectively. I have been privileged to coach Aleksandre Popov, the world’s fastest swimmer, Aleksandre Popov the World 100m Freestyle helped Michael to improve his technique and champion in 1994 and 1998, double Olympic educate himself in the way champions should Champion in the 50 and 100m Freestyle in behave. -

Code De Conduite Pour Le Water Polo

HistoFINA SWIMMING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS AT OLYMPIC GAMES Last updated in November, 2016 (After the Rio 2016 Olympic Games) Fédération Internationale de Natation Ch. De Bellevue 24a/24b – 1005 Lausanne – Switzerland TEL: (41-21) 310 47 10 – FAX: (41-21) 312 66 10 – E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fina.org Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2013 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret CONTENTS OLYMPIC GAMES Swimming – 1896-2012 Introduction 3 Olympic Games dates, sites, number of victories by National Federations (NF) and on the podiums 4 1896 – 2016 – From Athens to Rio 6 Olympic Gold Medals & Olympic Champions by Country 21 MEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 22 WOMEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 82 FINA Members and Country Codes 136 2 Introduction In the following study you will find the statistics of the swimming events at the Olympic Games held since 1896 (under the umbrella of FINA since 1912) as well as the podiums and number of medals obtained by National Federation. You will also find the standings of the first three places in all events for men and women at the Olympic Games followed by several classifications which are listed either by the number of titles or medals by swimmer or National Federation. It should be noted that these standings only have an historical aim but no sport signification because the comparison between the achievements of swimmers of different generations is always unfair for several reasons: 1. The period of time. The Olympic Games were not organised in 1916, 1940 and 1944 2. The evolution of the programme. -

1/4/2004 Piscina Olímpica Encantada T

Untitled 1/5/04 10:24 AM Licensed to Natacion Fernando Delgado Hy-Tek's Meet Manager II WINTER TRAINING MEET - 1/4/2004 PISCINA OLÍMPICA ENCANTADA TRUJILLO ALTO, PUERTO RICO Results Event 1 Women Open 200 LC Meter Medley Relay =============================================================================== MEET RECORD: * 2:07.03 1/5/2003 SYRACUSE, SYRACUSE- R Wrede, J Jonusaitis, E McDonough, C Jansen School Seed Finals =============================================================================== 1 NOTRE DAME SWIMMING 'A' 2:00.78 2:05.38* 2 NOTRE DAME SWIMMING 'B' 2:05.85 2:06.39* 3 SYRACUSE ORANGEMEN 'A' 2:04.13 2:07.59 4 YALE 'A' 1:59.10 2:09.30 5 ST'S. JOHNS UNIVERSITY 'A' 1:58.35 2:09.94 6 NADADORES SANTURCE 'A' 2:11.51 2:12.48 7 SETON HALL UNIVERSITY 'A' 2:07.98 2:13.43 8 YALE 'B' 2:03.60 2:13.86 9 ST'S. JOHNS UNIVERSITY 'B' 2:01.50 2:14.43 10 GEORGETOWN SWIMMING 'A' 2:10.33 2:15.81 11 ST'S. JOHNS UNIVERSITY 'C' 2:05.00 2:16.53 12 BRANDIES UNIVERSITY 'A' 3:11.00 2:17.50 13 YALE 'C' 2:05.70 2:17.73 14 SETON HALL UNIVERSITY 'B' 2:15.64 2:20.05 15 NADADORES SANTURCE 'B' 2:15.87 2:20.21 16 NOTRE DAME SWIMMING 'C' 2:10.77 2:22.08 17 GEORGETOWN SWIMMING 'B' 2:14.55 2:22.68 18 MONTCLAIR STATE UNIVERSITY 'A' 2:07.30 2:29.65 19 BRANDIES UNIVERSITY 'B' 3:20.00 2:29.75 Event 2 Men Open 200 LC Meter Medley Relay =============================================================================== MEET RECORD: * 1:53.79 1/5/2003 YALE UNIVERSITY, YALE- School Seed Finals =============================================================================== 1 SETON HALL UNIVERSITY 'A' 1:44.09 1:51.80* 2 YALE 'A' 1:44.30 1:53.18* 3 SYRACUSE ORANGEMEN 'A' 1:46.22 1:54.65 4 NADADORES SANTURCE 'A' 1:58.39 1:55.65 5 NADADORES SANTURCE 'B' 2:02.01 1:56.01 6 YALE 'B' 1:49.70 1:56.66 7 ST'S. -

USA TEAM: 2017 WORLD UNIVERSITY GAMES August 19-30, 2017, Taipei City, Taiwan

USA TEAM: 2017 WORLD UNIVERSITY GAMES August 19-30, 2017, Taipei City, Taiwan INTRODUCTION The World University Games is the American term for “Universiade,” an international multi-sport event organized for university athletes by the International University Sports Federation (FISU). The Universiade is an international sporting and cultural festival, staged every two years in a different city around the world, representing both winter and summer competitions. It is second only in importance to the Olympic Games. THE USA TEAM (see: www.wugusa.com) The 2017 Summer Games in Taipei City, Taiwan will have U.S. representation in up to 22 sports. By contrast, the 2015 American team had 600 athletes and staff in Gwangju, South Korea. The following 22 sports competitions are open for U.S. representation in Taiwan: Athletics/Track and Field Football (Soccer) Table Tennis Archery Golf Taekwondo Badminton Gymnastics (Artistic) Tennis Baseball Gymnastics (Rhythmic) Volleyball Basketball Judo Water Polo Cue Sports (Billiards) Roller Sports Weightlifting Diving Swimming Wushu Fencing AMERICAN SUCCESS AT THE WORLD UNIVERSITY GAMES: The U.S.A. won a total of 54 medals at the 2015 Summer Games, finishing 5th in the world. Many now-famous athletes have represented the U.S.A. in previous WUG competitions prior to gaining stardom in the Olympics and professional sports. These include such elite athletes as Michael Johnson (Track), Charles Barkley and Larry Bird (Men’s Basketball), Matt Biondi and Michael Phelps (Swimming), and Lisa Leslie (Women’s Basketball). It will be exciting to see who the next future American star will be from this current pool of U.S. -

II~Ny Ore, Continue Their Dominance of Their Respective Events

I'_l .N" l'.l('l FI4' There are different opportunities f II A .~1 I' I qi ~ ~ II I i ~ au'aiting all swimmers the year after an Olympic Games. By BtdD ~i,VmHllnoin.~,~i~ tions' exciting new talent to showcase its potential. Neil Walker, FUKUOKA, Japan--The post-Olympic year provides different op- Lenny Krayzelburg, Mai Nakamura, Grant Hackett, Ian Thorpe and portunities for swimmers. others served notice to the swimming world that they will be a force For the successful Atlanta Olympians, the opportunity to contin- to be reckoned with leading up to the 2000 Sydney Olympics. ue their Olympic form still remains, or they can take a back seat The meet was dominated once again by the U.S. and Australian with a hard-earned break from international competition. teams, who between them took home 31 of the 37 gold medals. For those who turned in disappointing results in Atlanta, there Japan (2), Costa Rica (2), China (i) and Puerto Rico (1) all won was the opportunity to atone for their disappointment and return to gold, while charter nation Canada failed to win an event. world-class form. The increasing gap between the top two nations and other com- And for others, the post-Olympic year provides the opportunity peting countries must be a concern for member federations in an era to break into respective national teams and world ranking lists while when most major international competitions are seeing a more even gaining valuable international racing experience. spread of success among nations. The 1997 Pan Pacific Championships Aug. -

FINA Champions Swim Series 2019 - Athletes List

Published on fina.org - Official FINA website (//www.fina.org) FINA Champions Swim Series 2019 - Athletes List Updated on: 19.04.2019 Guangzhou (CHN) - Men 50m Freestyle - USA Anthony Ervin - GBR Ben Proud - ITA Andrea Vergani - RUS Vladimir Morozov 100m Freestyle - RUS Vladimir Morozov - BEL Pieter Timmers - RUS Kliment Kolesnikov - RSA Chad Le Clos 200m Freestyle - CHN Sun Yang - RSA Chad Le Clos - LTU Danas Rapsys - CHN Wang Shun 400m Freestyle - ITA Gabriele Detti - CHN Sun Yang - AUS Jack McLoughlin - UKR Mykhailo Romanchuk 50m Backstroke - RUS Kliment Kolesnikov - ROU Robert Glinta - RUS Vladimir Morozov - USA Michael Andrew 100m Backstroke - CHN Xu Jiayu - RUS Kliment Kolesnikov - JPN Ryosuke Irie - ROU Robert Glinta 200m Backstroke - CHN Xu Jiayu - JPN Ryosuke Irie - LTU Danas Rapsys - CHN Li Guangyuan 50m Breaststroke - BRA Joao Gomes Jr - ITA Fabio Scozzoli - BRA Felipe Lima - USA Michael Andrew 100m Breaststroke - RUS Anton Chupkov - NED Arno Kamminga - ITA Fabio Scozzoli - USA Michael Andrew 200m Breaststroke - KAZ Dmitry Balandin - RUS Anton Chupkov - JPN Ippei Watanabe - CHN Qiu Haiyang 50m Butterfly - GBR Ben Proud - BRA Nicholas Santos - UKR Andriy Govorov - USA Michael Andrew 100m Butterfly - RSA Chad Le Clos - RUS Andrei Minakov - USA Michael Andrew - CHN Li Zhuhao 200m Butterfly - JPN Masato Sakai - RSA Chad Le Clos - CHN Li Zhuhao - CHN Wang Zhou 200m Ind. Medley - CHN Wang Shun - CHN Qin Haiyang - USA Michael Andrew - CHN Wang Yizhe Guangzhou (CHN) - Women 50m Freestyle - DEN Pernille Blume - SWE Sarah Sjostrom - NED -

Analysis of Stroke Rates in Freestyle Events at 2000 Olympics

ANALYSIS OF STROKE RATES IN FREESTYLE EVENTS AT 2000 OLYMPICS By David Pyne & Cassie Trewin Department of Physiology, Australian Institute of Sport The aim of this article is to examine the patterns of stroke rates of successful swimmers during the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. Stroke rates of swimmers in the Final (top 8 swimmers) of selected Freestyle events were taken from the Competition Analysis of the 2000 Olympic Games (courtesy of the Biomechanics Department, Australian Institute of Sport). The stroke rates for each 25, 50 or 100m race split and placing in the 50, 100, 200 and 400 m freestyle events were collated. The interesting questions are … Were there differences in stroke rates between the sprint (50 and 100m) and middle-distance (200 and 400m) events? Were there any differences in stroke rates between the Men’s and Women’s events? How much variation in stroke rate was evident between swimmers in the same event? And how much difference was observed between first and last lap stroke rates compared to the average for the event for each individual swimmer. The individual and mean stroke rates for each of the finalists in the 50, 100, 200 and 400 Freestyle events are presented in Table 1. Statistical analysis (data not shown) indicated that there were no significant correlations between average stroke rate on any lap and final placing. The only exception was the Women’s 400m Freestyle where the placegetters had a significantly higher average stroke rate over the race than those swimmers finishing outside the medals. This indicates that there is considerable variation in stroke rate between different swimmers at the Olympic level. -

Swimming Australia

SWIMMING SPECIAL EDITION IN AUSTRALIA PREVIEW PRESSURE SITUATIONS - NO WORRIES! An ultralight, low resistance racing goggle, the Stealth MKII features extended arms and a 3D seal to relieve pressure on and around the eyes. Stealth MKII Immerse yourself in Vorgee’s full product range at vorgee.com © Delly Carr Swimming Australia Trials, tribulations and testing times for Tokyo as our swimmers face their moments of truth in Adelaide ASCTA engaged swimming media expert Ian Hanson to profile a selection of athletes that will line up in Adelaide from June 12-17 for the 2021 Australian Swimming Trials at the SA Aquatic & Leisure Centre, after a frantic and frenetic time where Selection Criteria has changed with the inclusion of contingencies and recent lockdowns, forcing WA and Victorian Olympic and Paralympic hopefuls into Queensland. It will be a testing Trials in more ways than one - for swimmers, coaches and event staff as they work round the clock to give the class of 2020-21 a crack at their Olympic and Paralympic dreams. Here Ian Hanson provides his insight into the events that will seal the Tokyo team for the Games. Please enjoy and we wish the best of luck to all coaches and athletes at the Australian Swimming Trials. WOMEN 2021 © Delly Carr Swimming Australia WOMEN 50m Freestyle WORLD RECORD: Sarah Sjostrom, Sweden, 23.67 (2017) AUSTRALIAN RECORD: Cate Campbell, 23.78 (2018) Olympic QT: 24.46 Preview: An event shared at Australian Championship level by the Campbell sisters from Knox Pymble (Coach: Simon Cusack) since Cate Campbell won her first Australian title in 2012 - the first of her seven National championship wins. -

NCMS Zooms to 8Th Place Team Finish at 2014 Spring Nationals by Don Gilchrist

NCMS Zooms to 8th place team finish at 2014 Spring Nationals By Don Gilchrist Seventeen members of NCMS shined at Spring Nationals, May 1-4, at the George F Hanes International Swim Center, Santa Clara, California. This is the pool where the Olympic legends competed and trained, and considered the epicenter of competitive swimming over the last 75 years. Enthusiasm and excitement was rampant and gave rise to great swims by NC swimmers and fellow master swimmers. More recent legends participated and provided much thrill. They included Olympians Matt Biondi, Anthony Ervin, Josh Davis and Nathan Adrian (18.78 50 free and 41.13 100 free). NCMS member and national legend E Ole Larson, age 93, proved age is no hindrance by sweeping six events. Taking gold in all and having to purchase another bag to carry home the loot. One incredible feat! Below: Ole finishes the 1000 yd Freestyle Below: Matt Biondi and Jenny Perrottet, our secretary. For those who have thought about attending a USMS National Event, please view the Spring National wrap up, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m31VCsfkQPc&list=UUieORPCvi3T59wtqHLvbeww Other first place finishes came from Barbara Crowder, Elizabeth Novak and Jon Klein but much contribution in scoring and enthusiasm came from others; Robert Crowder, Melissa Gass, Dana Greene, Kevin Happ, Stacey Harris, Amy Holland, Paul Kern, Jamie Miller, Steve Pegram, Jennifer Perrottet, Carol Redfield, Amanda Rubel and Don Gilchrist. Jamie and Jenny received by informal vote the toughness award by competing in the 200 butterfly. There were 2249 participants making this event one of the largest USMS national events ever. -

Florida Swimming & Diving

FLORIDA SWIMMING & DIVING 2015-16 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT FLORIDA SWIMMING & DIVING 2015-16 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT 2015-16 SCHEDULE Date Meet Competition Site Time (ET) 2015 Fri.-Sun. Sep. 18-20 All Florida Invitational Gainesville, FL All Day Thu. Oct. 8 Vanderbilt (Women Only - No Divers)* Nashville, TN 7 p.m. Sat. Oct. 10 Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 10 a.m. Fri-Sat. Oct. 16-17 Texas/Indiana Austin, TX 7 p.m. Fri (50 LCM) / Sat (25 SCY) Fri. Oct. 30 Georgia (50 LCM)* Gainesville, FL 11 a.m. Fri. Nov. 6 South Carolina* Gainesville, FL 2 p.m. Fri-Sun. Nov. 20-22 Buckeye Invitational Columbus, OH All Day Thu-Sat. Dec. 3-5 USA Swimming Nationals (50 LCM) Federal Way, WA All Day Tue-Sun. Dec. 15-20 USA Diving Nationals Indianapolis, IN All Day 2016 Sat. Jan. 2 FSU Gainesville, FL 2 p.m. Sat. Jan. 23 Auburn (50 LCM)* Gainesville, FL 11 a.m. Sat. Jan. 30 Tennessee* Knoxville, TN 10 a.m. Tue-Sat. Feb. 16-20 SEC Championships Columbia, MO All Day Fri-Sun. Feb 26-28 Florida Invitational (Last Chance) Gainesville, FL All Day Mon-Wed. March 7-9 NCAA Diving Zones Atlanta, GA All Day Thu-Sat. March 16-19 Women’s NCAA Championships Atlanta, GA All Day Thu-Sat. March 23-26 Men’s NCAA Championships Atlanta, GA All Day Key: SCY - Standard Course Yards, LCM - Long Course Meters, * - Denotes SEC events 1 FLORIDA SWIMMING & DIVING 2015-16 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT CONTENTS / QUICK facts Schedule ......................................1 Elisavet Panti ..........................33 Gator Men’s Bios – Freshmen ..................