Men's Olympic Swimming Sinks While Title IX Swims Megan Ryther

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

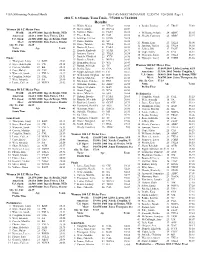

2004 Olympic Trials Results

USA Swimming-National Meets Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 12:55 PM 1/26/2005 Page 1 2004 U. S. Olympic Team Trials - 7/7/2004 to 7/14/2004 Results 13 Walsh, Mason 19 VTAC 26.08 8 Benko, Lindsay 27 TROJ 55.69 Women 50 LC Meter Free 15 Silver, Emily 18 NOVA 26.09 World: 24.13W 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 16 Vollmer, Dana 16 FAST 26.12 9 Williams, Stefanie 24 ABSC 55.95 American: 24.63A 2000 Dara Torres, USA 17 Price, Keiko 25 CAL 26.16 10 Shealy, Courtney 26 ABSC 55.97 18 Jennings, Emilee 15 KING 26.18 U.S. Open: 24.50O 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 19 Radke, Katrina 33 SC 26.22 Meet: 24.90M 2000 Dara Torres, Stanfor 11 Phenix, Erin 23 TXLA 56.00 20 Stone, Tammie 28 TXLA 26.23 Oly. Tr. Cut: 26.39 12 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 56.02 21 Boutwell, Lacey 21 PASA 26.29 Name Age Team 13 Jeffrey, Rhi 17 FAST 56.09 22 Harada, Kimberly 23 STAR 26.33 Finals Time 14 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 56.11 23 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 26.34 15 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 56.19 24 Daniels, Elizabeth 22 JCCS 26.36 Finals 16 Nymeyer, Lacey 18 FORD 56.56 25 Boncher, Brooke 21 NOVA 26.42 1 Thompson, Jenny 31 BAD 25.02 26 Hernandez, Sarah 19 WA 26.43 2 Joyce, Kara Lynn 18 CW 25.11 27 Bastak, Ashleigh 22 TC 26.47 Women 100 LC Meter Free 3 Correia, Maritza 22 BA 25.15 28 Denby, Kara 18 CSA 26.50 World: 53.66W 2004 Libby Lenton, AUS 4 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 25.22 29 Ripple Johnston, Shell 23 ES 26.51 American: 53.99A 2002 Natalie Coughlin, U 5 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 25.27 29 Medendorp, Meghan 22 IST 26.51 U.S. -

Novos Recordes

NOVOS RECORDES 28/09/2014 – ATLETISMO Maratona de Berlim Distância Novo/a Recordista Recordista Anterior Novo Recorde Recorde Anterior Data e Local Recorde Ant. Maratona Dennis Kimetto (QUE) Wilson Kipsang (QUE) 2:02:57 2:03:23 29/09/13 - Berlim 15/02/2014 – ATLETISMO INDOOR Donetsk, Ucrânia Prova Novo/a Recordista Recordista Anterior Novo Recorde Recorde Anterior Data e Local Recorde Ant. Salto com Renaud Lavillenie Sergey Bubka (UKR) 6:16 6:15 21/02/93 - Vara (indoor) (FRA) Donetsk 29/09/2013 – ATLETISMO Maratona de Berlim Distância Novo/a Recordista Recordista Anterior Novo Recorde Recorde Anterior Data e Local Recorde Ant. Maratona Wilson Kipsang (QUE) Patrick Makau (QUE) 2:03:23 2:03:38 25/09/11 - Berlim 07/09/2012 – ATLETISMO Diamond League, Bruxelas Prova Novo/a Recordista Recordista Anterior Novo Recorde Recorde Anterior Data e Local Recorde Ant. 110m com Aries Merrit (USA) Dayron Robles (CUB) 12.80 12.87 12/06/08 - barreiras Ostrava masc 11/08/2012 – ATLETISMO Olimpíadas de Londres Prova Novo/a Recordista Recordista Anterior Novo Recorde Recorde Anterior Data e Local Recorde Ant. 4x100 masc Jamaica (Nesta Carter, Jamaica (Nesta Carter, 36.84 37.04 04/09/11 – Michael Frater, Yohan Michael Frater, Yohan Daegu Blake, Usain Bolt) Blake, Usain Bolt) Marcha Yelena Vera Sokolova (RUS) 01:25:02 01:25:08 26/02/11 - 20km fem Lashmanova(RUS) Sochi 10/08/2012 – ATLETISMO Olimpíadas de Londres Prova Novo/a Recordista Recordista Anterior Novo Recorde Recorde Anterior Data e Local Recorde Ant. 4x100 fem USA (Tianna Madison, Alemanha Oriental 40.82 41.37 06/10/85 – Allyson Felix, Bianca Canberra Knight, Carmelita Jeter) 09/08/2012 – ATLETISMO Olimpíadas de Londres Prova Novo/a Recordista Recordista Anterior Novo Recorde Recorde Anterior Data e Local Recorde Ant. -

OLYMPIC SWIMMING MEDAL STANDINGS Country Gold Silver Bronze Total

Speedo and are registered trademarks of and used under license from Speedo International trademarks of and used under license from Limited. registered are Speedo and CULLEN JONES RISE AND SWIM SPEED SOCKET GOGGLE SPEEDOUSA.COM ANTHONY ERVIN • 2000, 2012, 2016 OLYMPIAN discover your speed. new! EDGE COMFORTABLE, HIGH VELOCITY SWIM FINS To learn more, contact your local dealer or visit FINISinc.com STRENGTH DOES NOT COME FROM PHYSICAL CAPACITY. IT COMES FROM AN INDOMITABLE WILL. arenawaterinstinct.com SEPTEMBER 2016 FEATURES COACHING 010 ROCKIN’ IN RIO! 008 LESSONS WITH Winning half of the events and col- THE LEGENDS: lecting more than three times more SHERM CHAVOOR medals than any other country, Team by Michael J. Stott USA dominated the swimming compe- PUBLISHING, CIRCULATION tition at the XXXI Olympiad in Brazil. 040 Q&A WITH AND ACCOUNTING COACH www.SwimmingWorldMagazine.com 012 2016 RIO DE JANEIRO TREVOR MIELE Chairman of the Board, President - Richard Deal OLYMPICS: PHOTO by Michael J. Stott [email protected] GALLERY Publisher, CEO - Brent T. Rutemiller Photos by USA TODAY Sports 042 HOW THEY TRAIN [email protected] ELISE GIBBS Circulation/Art Director - Karen Deal 031 GIRLS’ NATIONAL by Michael J. Stott [email protected] HIGH SCHOOL Circulation/Operations Manager - Taylor Brien [email protected] CHAMPIONSHIPS: TRAINING THE NUMBERS Advertising Production Coordinator - Betsy Houlihan SPEAK FOR 039 DRYSIDE [email protected] THEMSELVES TRAINING: THE by Shoshanna Rutemiller NEED FOR SPEED EDITORIAL, PRODUCTION, The Carmel (Ind.) High School by J.R. Rosania MERCHANDISING, MARKETING AND girls’ swimming team just keeps ADVERTISING OFFICE on winning...and doing so with JUNIOR 2744 East Glenrosa Avenue, Phoenix, AZ 85016 class. -

January-February 2003 $ 4.95 Can Alison Sheppard Fastest Sprinter in the World

RUPPRATH AND SHEPPARD WIN WORLD CUP COLWIN ON BREATHING $ 4.95 USA NUMBER 273 www.swimnews.com JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2003 $ 4.95 CAN ALISON SHEPPARD FASTEST SPRINTER IN THE WORLD 400 IM WORLD RECORD FOR BRIAN JOHNS AT CIS MINTENKO BEATS FLY RECORD AT US OPEN ������������������������� ��������������� ���������������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������ � �������������������������� � ����������������������� �������������������������� �������������������������� ����������������������� ������������������������� ����������������� �������������������� � ��������������������������� � ���������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������� ��������������������������� �������������������������� ������������ ������� ���������������������������������������������������� ���������������� � ������������������� � ��������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������� ����������������������������� ��������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������������������� ������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������� ������������������� SWIMNEWS / JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2003 3 Contents January-February 2003 N. J. Thierry, Editor & Publisher CONSECUTIVE NUMBER 273 VOLUME 30, NUMBER 1 Marco Chiesa, Business Manager FEATURES Karin Helmstaedt, International Editor Russ Ewald, USA Editor 6 Australian SC Championships Paul Quinlan, Australian Editor Petria Thomas -

San Antonio Sports Hall of Fame Auction Items

SAN ANTONIO SPORTS HALL OF FAME TRIBUTE AUCTION FEBRUARY 10, 2005 Instructions for the Auction: 1. Please follow the instructions on the Bid Sheets for the silent auction. 2. Minimum Bid is the Starting Bid. 3. Incremental Increases should be followed or your Bid will be deleted unless it is higher than required. 4. Please note all Gift Certificates have expiration dates. 5. Check out will begin after all the Inductees have been presented. 6. Visa, MasterCard or American Express, Cash and Checks are accepted. 7. Live Auction will be paid for immediately by successful bidder. Bid High & Good Luck! Page 1 Live Auction 1……….Mexican Fiesta Party at Rio Plaza Courtyard Party for up to 75 friends at Rio Plaza on the Riverwalk; Mexican Buffet and 'Tex Mex' drinks to include Margaritas, Wine and Beer accompanied by light entertainment. Book Soon! Based on Availability. Value $2,500 Donated by Rio Plaza and Weston Events 2……….Wine Lovers Extravaganza Explore the Napa Valley with a Weekend for Two at Trinchero Estates Bed & Breakfast known for their world class wines and located in the heart of the wine country with gourmet Breakfasts, Tour & Tasting. Additionally Two Nights-Stay in San Francisco at the Marriott Airport San Francisco. Airfare for Two included. Donated by Trinchero Winery and Airfare Courtesy of The Miner Corporation 3……….Vacation on the Beach Manzanillo Villa for 8. One-week stay in a 4-Bedroom/4-Bath villa located on a cliffside overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Swimming pool. Cook/Housekeeper for hire. Santiago Country Club Membership. Fishing options. -

USA Swimming-Nat. Meets Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 3:13 PM 6/26/2008 Page 1 2008 U.S

USA Swimming-Nat. Meets Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 3:13 PM 6/26/2008 Page 1 2008 U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Swimming - 6/29/2008 to 7/6/2008 Psych Sheet 51 Rathgeber, Geoff 22 SoNoCo Swim Club-CT/Harvar4:29.11 Event 1 Men 400 LC Meter IM 52 Murry, Steven 21 Excel Aquatics-SE 4:29.25 World: 4:06.22 4/1/2007 Michael Phelps, USA 53 Tyler, Alex 19 Oakland Live Y'E-MI/Univ4:29.34 o American: 4:06.22 4/1/2007 Michael Phelps, USA 54 Koerten, Brett 22 University of Wi-WI 4:29.58 U.S. Open: 4:08.41 7/7/2004 Michael Phelps, N. Baltimore 55 Bollier, Bobby 18 Kansas City Blaz-MV 4:29.65 Meet: 4:08.41 7/7/2004 Michael Phelps, N. Baltimore 56 Criste, John 19 Mission Viejo Na-CA/Stanfo4:29.89 Trials Cut: 4:30.49 57 Peterson, Chip 20 North Carolina A-NC 4:29.90 Name Age Team Seed Time 58 Hamilton, Neal 22 Thunderbolt Aqua-PC/BYU4:30.03 1 Phelps, Michael 22 Club Wolverine-MI/NBAC4:06.22 59 Vogt, Ian 18 Nova of Virginia-VA/U of V4:30.09 2 Lochte, Ryan 23 Daytona Beach-FL/DBS 4:09.74 60 Wollner, Samuel 22 Asphalt Green Un-MR/Harvar4:30.18 3 Vendt, Erik 27 Club Wolverine-MI 4:12.69 61 Smalley, Maverick 20 The Woodlands Sw-GU/SMU4:30.20 4 Margalis, Robert 26 Athens Bulldog S-GA/SPA4:12.92 62 Kline, Peter 18 San Luis Obispo-CA/Cal Pol4:30.37 5 Mellors, Pat 22 Jewish Community-AM/Virgin4:12.94 63 Houser, Matt 17 Greenville Swim-NC 4:30.39 6 Shanteau, Eric 24 Longhorn Aquatic-ST/Swim4:14.33 A 64 Haley, Alec 23 Indiana Universi-IN 4:30.45 7 Vanderkaay, Alex 22 Univ. -

Men's Butterfly

Men’s All-Time World LCM Performers-Performances Rankings Page 1 of 125 100 METER BUTTERFLY Top 6460 Performances 49.82** Michael Phelps, USA 13th World Championships Rome 08-01-09 (Splits: 23.36, 49.82 [26.46]. (Reaction Time: +0.69. (Note: Phelps’ third world-record in 100 fly, second time in 23 days he has broken it. Last man to break wr twice in same year was Australian Michael Klim, who did it twice in two days in December of 1999 in Canberra, when he swam 52.03 [12/10] and 51.81 two days later. (Note: first time record has been broken in Rome and/or Italy. (Note: Phelps’ second-consecutive gold. Ties him with former U.S. teammate Ian Crocker for most wins in this event [2]. Phelps also won @ Melbourne [2007] in a then pr 50.77. U.S. has eight of 13 golds overall. (Note: Phelps first man to leave a major international competition holding both butterfly world records since Russia’s Denis Pankratov following the European Championships in Vienna 14 years ago [August 1995]. Pankratov first broke the 200 world record of USA’s Melvin Sewart [1:55.69 to win gold @ the 1991 World Championships in Perth] with his 1:55.22 @ Canet in June of ’95. The Russian then won the gold and broke the global-standard in the 100 w/his 52.32 @ Vienna two months later. That swim took down the USA’s Pablo Morales’ 52.84 from the U.S. World Championship Trials in Orlando nine years earlier [June ‘86]. -

Rice March Madness 2017 - 3/11/2017 Rice University, Houston, TX, Sanction #: 257-S005 FINAL Results - March Madness

Rice University HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 5.0 - 12:03 PM 3/22/2017 Page 1 Rice March Madness 2017 - 3/11/2017 Rice University, Houston, TX, Sanction #: 257-S005 FINAL Results - March Madness Women 25-29 50 Yard Freestyle NATL: 22.62 1/25/2014 MADISON KENNEDY Name Age Team Finals Time 1 Wlostowska, Kamila 27 Rice Aquatic Masters-25 24.13 Women 25-29 100 Yard Freestyle NATL: 49.18 2/24/2013 KIM VANDENBERG 1 Fields, Liz A 28 Houston Cougar Masters-25 1:00.40 28.90 1:00.40 Women 25-29 100 Yard Backstroke NATL: 54.06 5/23/2010 TANICA JAMISON 1 Fields, Liz A 28 Houston Cougar Masters-25 1:08.74 33.15 1:08.74 Women 25-29 200 Yard Backstroke NATL: 1:56.87 2/28/2015 F PELLEGRINI 1 Clapp, Marissa L 29 Rice Aquatic Masters-25 2:14.28 31.37 1:05.45 1:39.65 2:14.28 2 Fields, Liz A 28 Houston Cougar Masters-25 2:26.48 33.93 1:11.53 1:49.52 2:26.48 Women 25-29 50 Yard Breaststroke NATL: 27.10 4/30/2016 KATIE MEILI 1 Garzon Munguia, Julieta 28 Rice Aquatic Masters-25 34.72 Women 25-29 100 Yard Breaststroke NATL: 59.58 2/6/2010 MEGAN JENDRICK 1 Clapp, Marissa L 29 Rice Aquatic Masters-25 1:06.67 31.79 1:06.67 2 Garzon Munguia, Julieta 28 Rice Aquatic Masters-25 1:17.52 36.72 1:17.52 Women 25-29 200 Yard Breaststroke NATL: 2:09.05 2/6/2010 MEGAN JENDRICK 1 Clapp, Marissa L 29 Rice Aquatic Masters-25 2:25.02 33.20 1:09.85 1:47.30 2:25.02 Women 25-29 50 Yard Butterfly NATL: 24.41 5/22/2010 TANICA JAMISON 1 Garzon Munguia, Julieta 28 Rice Aquatic Masters-25 29.66 Women 25-29 100 Yard IM NATL: 54.43 2/6/2010 MEGAN JENDRICK 1 Wlostowska, Kamila 27 Rice Aquatic Masters-25 -

Tiger Times SPECIAL EDITION July / August 2020

SWIMMER’S NEWSLETTER FOR PRINCETON TIGER AQUATICS CLUB Tigers are Back in the Pool! by: Aditi Pavuluri It’s been a strange past few months for swimmers across the country, and one of the few times in history where there have been no competitions or practice taking place. The Olympics were postponed for the first time ever, and competitive swimmers across the globe are wondering when they can start competing again. As of two weeks ago, swimmers have taken to the pool for the first time in months. To pass the time, they’ve been working out over Zoom, and doing as much work as they could while still socially distanced. By working on technique, starts, turns, and speed, the Tigers have been trying to get in as much swimming as they can to make up for lost time. It will be a fresh start for us, and a way to start using muscles that haven’t been awoken in months. And though we’ve been staying in shape, we might not necessarily have been staying in swimming shape. Getting back into the pool is something that every swimmer is having to experience, and know that we’re in this together. So right now is the perfect time to improve on something that you’ve been holding off on during competition season. Our perspective might have to change from “getting back to where we came from” to “how far we can go”. Take advantage of this new and unusual time to better yourself as a swimmer. Go Tigers! SWIMMER’S NEWSLETTER FOR PRINCETON TIGER AQUATICS CLUB Monthly Motivation Ready for Normal. -

USA Swimming 2007-2008 National Team – Men: 1500 Free 100 Back

USA Swimming 2007-2008 National Team – Men: Qualifying Criteria: Top six times in Olympic events swum in finals from World Championships, Pan AMs, World University Games and Nationals. Relay leadoffs and time trials not included; times include times from Semi- Finals and Finals (A,B,C) only 50 free Ben Wildman-Tobriner Nationals Stanford Swimming Ted Knapp/Skip Kenney Cullen Jones Nationals North Carolina State Aquatics Brooks Teal Nick Brunelli Nationals Sun Devil Aquatics Mike Chasson Donald Scott Goodrich WUGS Auburn University Swim Team Richard Quick Gabe Woodward Pan Ams Bakersfield Swim Club Keith Moore Gary Hall Pan Ams The Race Club Mike Bottom Garrett Weber- Gale Nationals Longhorn Aquatics Eddie Reese 100 Free Jason Lezak World Champs Unattached Ted Knapp/Skip Kenney David Walters Nationals Longhorn Aquatics Eddie Reese Nick Brunelli Nationals Sun Devil Aquatics Mike Chasson Neil Walker Nationals Longhorn Aquatics Eddie Reese Garrett Weber- Gale Nationals Longhorn Aquatics Eddie Reese Jayme Cramer Nationals Southeastern Swimming Andy Pedersen 200 Free Michael Phelps World Champs Club Wolverine Bob Bowman Peter Vanderkaay Nationals Club Wolverine Bob Bowman Adam Ritter WUGS Tucson Ford Frank Busch Jayme Cramer Nationals Southeastern Swimming Andy Pedersen David Walters Nationals Longhorn Aquatics Eddie Reese Ricky Berens Nationals Longhorn Aquatics Eddie Reese 400 Free Peter Vanderkaay Nationals Club Wolverine Bob Bowman Larsen Jensen Nationals Trojan Swim Club David Salo Michael Phelps Nationals Club Wolverine Bob Bowman Erik -

Code De Conduite Pour Le Water Polo

HistoFINA SWIMMING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS AT OLYMPIC GAMES Last updated in November, 2016 (After the Rio 2016 Olympic Games) Fédération Internationale de Natation Ch. De Bellevue 24a/24b – 1005 Lausanne – Switzerland TEL: (41-21) 310 47 10 – FAX: (41-21) 312 66 10 – E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fina.org Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2013 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret CONTENTS OLYMPIC GAMES Swimming – 1896-2012 Introduction 3 Olympic Games dates, sites, number of victories by National Federations (NF) and on the podiums 4 1896 – 2016 – From Athens to Rio 6 Olympic Gold Medals & Olympic Champions by Country 21 MEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 22 WOMEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 82 FINA Members and Country Codes 136 2 Introduction In the following study you will find the statistics of the swimming events at the Olympic Games held since 1896 (under the umbrella of FINA since 1912) as well as the podiums and number of medals obtained by National Federation. You will also find the standings of the first three places in all events for men and women at the Olympic Games followed by several classifications which are listed either by the number of titles or medals by swimmer or National Federation. It should be noted that these standings only have an historical aim but no sport signification because the comparison between the achievements of swimmers of different generations is always unfair for several reasons: 1. The period of time. The Olympic Games were not organised in 1916, 1940 and 1944 2. The evolution of the programme. -

Southern California Swimming, Inc

$6 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA SWIMMING, INC. a local swimming committee of USA SWIMMING, INC 2011 Swim Guide Published by the House of Delegates of Southern California Swimming Jeri Marshburn, General Chairman Mary J. Swalley, Executive Director SWIM OFFICE 41 Hitchcock Way, Suite B Santa Barbara, California 93105-3101 Post Office Box 30530 Santa Barbara, CA 93130-0530 (805) 682-0135 In Southern California: (800) 824-6206 Monday - Friday, 9 a.m. - 5 p.m. FAX: (805) 687-4175 Visit SCS on the internet at www.socalswim.org Email: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Southern California Swimming Directory Page 3 Board of Directors & Board of Review Page 4 Committee Officers Page 6 Club Rosters Page 13 Swim Calendar Page 28 Rules and Procedures Page 43 Glossary for Southern California Swimming Page 44 Part One-General Rules and Procedures Page 47 I. Authority and Relationships Page 47 II. Integrity of the Competition Page 48 III. Registration and Affiliation Page 49 IV. Entry into the Competition Page 51 V. Administrative Procedures Page 53 VI. Southern California Swimming Funds Page 54 Part Two-Conduct of the Competition Page 58 I. Conduct of Meets, General Page 58 II. Conduct of Meets, "Timed Finals" Page 58 III. Conduct of Meets, "Heats and Finals" Page 59 IV. Conduct of Meets, "Time Trials" Page 60 V. Submission of Entries Page 60 VI. Limitation on Entries Page 61 VII. Entry Times Page 61 VIII. Errors Related to Entries Page 62 IX. Administration Page 62 Part Three-Senior Competition Page 64 I. Eligibility Page 64 II. Senior Invitationals Page 64 III.