The Mexican Mind; a Study of National Psy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rising Tide of Color by Lothrop Stoddard £ 6,00 Plus £ 1,50 P + P / [email protected]

Books online The Rising Tide of Color by Lothrop Stoddard £ 6,00 plus £ 1,50 p + p / [email protected] The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy by Lothrop Stoddard, A.M., Ph.D. (Harvard) Author of "The Stakes of the War," "Present-Day Europe: Its National States of Mind," "The French Revolution in San Domingo," Etc. With an Introduction by Madison Grant Chairman, New York Zoological Society; Trustee American Museum Of Natural History; Councillor American Geographical Society; Author Of " The Passing Of The Great Race" New York - 1922 CONTENTS Preface Introduction by Madison Grant PART I - The Rising Tide of Color i. The World of Color ii. Yellow Man's Land iii. Brown Man's Land iv. Black Man's Land v. Red Man's Land PART II - The Ebbing Tide of White vi. The White Flood vii. The Beginning of the Ebb viii. The Modern Peloponnesian War ix. The Shattering of White Solidarity PART III - The Deluge On The Dikes x. The Outer Dikes xi. The Inner Dikes xii. The Crisis of the Ages Return to Home Page Books online The Rising Tide of Color by Lothrop Stoddard PREFACE More than a decade ago I became convinced that the key-note of twentieth-century world-politics would be the relations between the primary races of mankind. Momentous modifications of existing race-relations were evidently impending, and nothing could be more vital to the course of human evolution than the character of these modifications, since upon the quality of human life all else depends. Acoordingly, my attention was thenceforth largely directed to racial matters. -

The Dominion News

The Dominion News A Dominion HOA Publication September 2012 Dominion Survey Please help The Dominion Homeowners Association Staff, Board Members, and General Manager improve services by completing a brief survey. The individual surveys are confidential with an independent company, Survey Monkey, automatically consolidating the results. Now is the time to let the HOA know how they are doing. Together we can keep The Dominion the premier community in San Antonio. The survey will be available electronically from August 24 through September 24, 2012. If you need a hard copy contact Julie Rincon at 210-698-1232. Landscape By mutual agreement, the contract with Native Land Design to perform maintenance for the HOA has been terminated effective immediately. The contract was due to expire December 31st. An interim contract, beginning September 1st, to perform maintenance until year end has been awarded to another contractor. In the meantime, a special sub- committee of the Landscape Committee has been working with a maintenance consultant to produce a standards of care document and a detailed Request For Proposal (RFP). Multiple maintenance contractors will be invited to bid for a new two year contract to begin January 1, 2013. A high level of professional maintenance is essential to keep our properties healthy and beautiful, especially during these times of severe weather conditions. The next large landscape and irrigation refurbishment is targeted on the east side of Dominion Drive starting at the intersection of Brenthurst heading north to Duxbury Park. Driving by this area, one can see deteriorated areas in need of maintenance. The focus is to fix areas most visible on the main corridors. -

Visitors Are Invited to a Countrywide Party in Mexico 08/07/2017 03:58 Pm ET

Bob Schulman, Contributor | Travel Editor, WatchBoom.com Visitors Are Invited To A Countrywide Party In Mexico 08/07/2017 03:58 pm ET MEXICO TOURISM BOARD You’re in luck if you happen to be in Mexico on Sept. 16. Wherever you are down there, don’t be surprised if you’re invited to the likes of colorful fiestas, mariachi shows, block parties and sing-alongs in the cantinas while fireworks liven up the sky that night. That’s because Sept. 16 is Mexico Independence Day, marking the day in 1810 when Father Miguel Hidalgo, in an impassioned speech in the little town of Dolores, urged Mexicans to rise up against the Spanish government. They did, sparking what became a 10-year war for independence. Kicking off a national celebration in Mexico City, the Mexican president will ring a bell and repeat Father Hidalgo’s iconic “Cry of Dolores.” In past years, better than a half-million merry-makers have turned out for the presidential event followed by musical performances and one of the world’s most spectacular fireworks shows.The Similar celebrations staged around Father Hidalgo’s cry (called “El Grito”) will take place in cities across the country. Out on the Yucatan Peninsula at Campeche, for example, tourists are welcome to join townsfolk whooping it up at the BOB SCHULMAN city’s Moch-Couho Plaza next to the government Church in Dolores where Father Hidalgo gave ‘El Grito.' palace. Down in Acapulco, you can join join the locals’ joyful chanting (all you need to do is shout “Viva” when everyone else does). -

El Grito De Dolores Worksheet Answer Key

El Grito De Dolores Worksheet Answer Key Septic and Alcaic Collins gobbled her jowl buffaloing impishly or lavishes apprehensively, is Shelby Prejudicialpolypous? AnaerobicMorgan directs: Putnam he topespartitions her hisdeclivity diffusers so sincerely naively and that inconsolably. Vassili acidify very inextinguishably. Bdo 56 60 guide 2020. WEB De Bois by Aldon Morris author of a Scholar Denied WEB Du Bois and available Birth of Modern Sociology. Today Mexican Independence Day is getting major celebration in Mexico bigger than Cinco de Mayo. Lesson-El Grito Mexican Independence-Reading-Comprehension Unit- Cultural. TITLE TYPE DESCRIPTION LANGUAGE LENGTH Stone. Famous speech- el Grito de Dolores the cleave of Dolores- called for Mexicans to. And rise not against the Spanish Crown an affect that is lost as el grito de Dolores the pursue of Dolores. Highly educated Creole priest assigned to less of Dolores September 16 110 El Grito de Dolores Led a rag-tag. Mexican Independence Day plans for Spanish class El grito de Dolores DIGITAL The Comprehensible. I will identify the key components of the Mexican Constitution of 124. Answer key 2pgsAlso included are some cultural notes and translations of. The several Of Jackson Worksheet Answers Buster The Body Crab Lyrics. See more ideas on el grito de dolores worksheet answer key. Artist suggest beyond the Mexican revolt group the Spanish. Celebracin de una misa patronal en la que lanza el Grito de Dolores. Related to explain its members, drama and farms and the paper, leading to loot as uneducated workers were not ordained through northwestern spain on el grito de dolores! In response France Britain and Spain sent naval forces to Veracruz Mexico. -

May Day History Famous May Birthdays Mother's Day History Cinco

MAY 2021 Skilled Nursing Mother’s Day History Mother’s Day began as a spring festival to celebrate “Mother Earth”. Then, it became a celebration of “Mother Church”. Finally, it became a day to celebrate all mothers. As Christianity 1306 Pelham Rd • Greenville, SC 29615 • (864) 286-6600 spread throughout Europe, the celebration became linked to Easter. Many churches celebrated “Mothering Sunday” on the fourth Sunday of Lent, the forty days leading up to Easter. It was Cinco de Mayo History a celebration of Mary, Mother of God. It became customary to Gables on Pelham offer small gifts or cakes to mothers on this day. The fifth of May is when Directors In the 1600s in England, “Mothering Day” was celebrated. This Americans celebrate an was a day when wealthy families gave their servants a day off to important battle in Mexican Sue Kennedy history with so much food and return to their homes to visit their mothers. Today, Mother’s Day is a celebration of all mothers. Campus Executive Director This idea began with two women—Julia Ward Howe and Anna Jarvis. Howe, a social reformer and music and fun that the real poet, wanted a day when mothers could celebrate peace, and she proposed calling it “Mother’s story behind the holiday is Olishia Gaffney Day for Peace” and wrote the first Mother’s Day Proclamation. often overlooked. While Cinco Director of Nursing de Mayo is often thought of as a In 1907, Anna Jarvis, who lived in Philadelphia, persuaded her mother’s church in Grafton, West Becky Hutto Virginia, to celebrate Mother’s Day on the second Sunday in May, which coincided with the celebration of Mexican Business Office Manager anniversary of her mother’s death. -

Indigenous and Cultural Psychology

Indigenous and Cultural Psychology Understanding People in Context International and Cultural Psychology Series Series Editor: Anthony Marsella, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii ASIAN AMERICAN MENTAL HEALTH Assessment Theories and Methods Edited by Karen S. Kurasaki, Sumie Okazaki, and Stanley Sue THE FIVE-FACTOR MODEL OF PERSONALITY ACROSS CULTURES Edited by Robert R. McCrae and Juri Allik FORCED MIGRATION AND MENTAL HEALTH Rethinking the Care of Refugees and Displaced Persons Edited by David Ingleby HANDBOOK OF MULTICULTURAL PERSPECTIVES ON STRESS AND COPING Edited by Paul T.P. Wong and Lilian C.J. Wong INDIGENOUS AND CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY Understanding People in Context Edited by Uichol Kim, Kuo-Shu Yang, and Kwang-Kuo Hwang LEARNING IN CULTURAL CONTEXT Family, Peers, and School Edited by Ashley Maynard and Mary Martini POVERTY AND PSYCHOLOGY From Global Perspective to Local Practice Edited by Stuart C. Carr and Tod S. Sloan PSYCHOLOGY AND BUDDHISM From Individual to Global Community Edited by Kathleen H. Dockett, G. Rita Dudley-Grant, and C. Peter Bankart SOCIAL CHANGE AND PSYCHOSOCIAL ADAPTATION IN THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Cultures in Transition Edited by Anthony J. Marsella, Ayda Aukahi Austin, and Bruce Grant TRAUMA INTERVENTIONS IN WAR AND PEACE Prevention, Practice, and Policy Edited by Bonnie L. Green, Matthew J. Friedman, Joop T.V.M. de Jong, Susan D. Solomon, Terence M. Keane, John A. Fairbank, Brigid Donelan, and Ellen Frey-Wouters A Continuation Order Plan is available for this series. A continuation order will bring deliv- ery of each new volume immediately upon publication. Volumes are billed only upon actual shipment. For further information please contact the publisher. -

Report of the National Psychology Project Team

Report of the Psychology Project Team: Establishment of a National Psychology Placement Office Report of the National Psychology Project Team: Establishment of a National Psychology Placement Office and Workforce Planning 15 January 2021 1 Report of the Psychology Project Team: Establishment of a National Psychology Placement Office Foreword Following a review of Eligibility Criteria for staff and senior grade psychologists in 2016, an Implementation Group was established to implement the revised standards. The Implementation Group recommended the establishment of a National Psychology Placement Office. Inter alia an action from the Department of Health, to prepare a workforce plan for psychological services in the HSE, including an examination of the framework for training psychologists for the health service and the type and skill-mix required for the future, was required, HSE Community Operations convened a Project Team to progress the recommendation of the Implementation Group and to make a contribution to a workforce plan for psychological services provided for, and funded by, the HSE. The Project Team that developed this Report included representation from Clinical, Counselling and Educational Psychology; Social Care, Disability, and Mental Health services; Community and Acute services, Operational and Strategic HR, and the Health and Social Care Professions office. The work of the Project Team was also informed by a stakeholder consultation process. Cross-sectoral and stakeholder involvement reflects the intent to ensure all relevant stakeholders continue to feed into the management of student placements and workforce planning into the future. It is anticipated that the governance and oversight structures to be established under the placement office will embody stakeholder collaboration and engagement. -

Get to Know: Mexico World Book® Online

World Book Advanced Database* World Book® Online: The trusted, student-friendly online reference tool. Name: ____________________________________________________ Date:_________________ Get to Know: Mexico Mexico is a large, populous Latin American country. The country’s history has been largely shaped by the Indian empires that thrived for hundreds of years and the Spaniards that ruled Mexico for 300 years. How much do you know about this country and its culture and history? Set off on a webquest to explore Mexico and find out! First, log onto www.worldbookonline.com Then, click on “Advanced.” If prompted, log on with your ID and Password. Find It! Find the answers to the questions below by using the “Search” tool to search key words. Since this activity is about Mexico, you can start by searching the key word “Mexico.” Write the answers on the lines provided or below the question. 1. Mexico has _______________ states and one federal district. 2. The capital and largest city of Mexico is ______________________. 3. Look at the image “Mexico and coat of arms.” What do each of the colored stripes stand for? (a) Green: ______________________ (b) White: ______________________ (c) Red: ______________________ 4. ______________________is Mexico’s highest mountain. 5. Mexicans celebrate their Independence Day on ______________________. 6. The great majority of Mexicans are ______________________, people of mixed ancestry. 7. The most popular sports in Mexico are ______________________ and ______________________. *Users of the Advanced database can find extension activities at the end of this webquest. © 2018 World Book, Inc. Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A. All rights reserved. World Book and the globe device are trademarks or registered trademarks of World Book, Inc. -

Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Class Struggle: a Critical Analysis of Mainstream and Marxist Theories of Nationalism and National Movements

NATIONALISM, ETHNIC CONFLICT, AND CLASS STRUGGLE: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF MAINSTREAM AND MARXIST THEORIES OF NATIONALISM AND NATIONAL MOVEMENTS Berch Berberoglu Department of Sociology University of Nevada, Reno Introduction The resurgence of nationalism and ethnonationalist con ict in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union and its associated Eastern European states in their transition from a form of socialism to a market- oriented direction led by bourgeois forces allied with world capitalism during the decade of the 1990s, has prompted a new round of discus- sion and debate on the origins and development of nationalism and the nation-state that has implications for contemporary nationalism and nationalist movements in the world today. This discussion and debate has been framed within the context of classical and contemporary social theory addressing the nature and role of the state and nation, as well as class and ethnicity, in an attempt to understand the relationship between these phenomena as part of an analysis of the development and transformation of society and social relations in the late twentieth century. This paper provides a critical analysis of classical and contemporary mainstream and Marxist theories of the nation, nationalism, and eth- nic con ict. After an examination of select classical bourgeois statements on the nature of the nation and nationalism, I provide a critique of contemporary bourgeois and neo-Marxist formulations and adopt a class analysis approach informed by historical materialism to explain the class nature and dynamics of nationalism and ethnonational con ict. Critical Sociology 26,3 206 berch berberoglu Mainstream Theories of the Nation and Nationalism Conventional social theories on the nature and sources of national- ism and ethnic con ict cover a time span encompassing classical to con- temporary statements that provide a conservative perspective to the analysis of ethnonational phenomena that have taken center stage in the late twentieth century. -

The Birth of Chinese Feminism Columbia & Ko, Eds

& liu e-yin zHen (1886–1920?) was a theo- ko Hrist who figured centrally in the birth , karl of Chinese feminism. Unlike her contem- , poraries, she was concerned less with China’s eds fate as a nation and more with the relation- . , ship among patriarchy, imperialism, capi- talism, and gender subjugation as global historical problems. This volume, the first translation and study of He-Yin’s work in English, critically reconstructs early twenti- eth-century Chinese feminist thought in a transnational context by juxtaposing He-Yin The Bir Zhen’s writing against works by two better- known male interlocutors of her time. The editors begin with a detailed analysis of He-Yin Zhen’s life and thought. They then present annotated translations of six of her major essays, as well as two foundational “The Birth of Chinese Feminism not only sheds light T on the unique vision of a remarkable turn-of- tracts by her male contemporaries, Jin h of Chinese the century radical thinker but also, in so Tianhe (1874–1947) and Liang Qichao doing, provides a fresh lens through which to (1873–1929), to which He-Yin’s work examine one of the most fascinating and com- responds and with which it engages. Jin, a poet and educator, and Liang, a philosopher e plex junctures in modern Chinese history.” Theory in Transnational ssential Texts Amy— Dooling, author of Women’s Literary and journalist, understood feminism as a Feminism in Twentieth-Century China paternalistic cause that liberals like them- selves should defend. He-Yin presents an “This magnificent volume opens up a past and alternative conception that draws upon anar- conjures a future. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of MEXICO the Classic Period to the Present

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MEXICO The Classic Period to the Present Created by Steve Maiolo Copyright 2014 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Section 1: The Maya The Mayan Creation Myth ........................................................................ 1 Ollama ..................................................................................................... 1 Mayan Civilization Social Hierarchy ....................................................................................... 2 Religion ................................................................................................... 3 Other Achievements ................................................................................ 3 The Decline of the Mayans ...................................................................... 3 Section 2: The Aztecs The Upstarts ............................................................................................ 4 Tenochtitlàn ............................................................................................. 4 The Aztec Social Hierarchy Nobility (Pipiltin) ....................................................................................... 5 High Status (not nobility) .......................................................................... 5 Commoners (macehualtin) ....................................................................... 6 Slaves ...................................................................................................... 6 Warfare and Education ........................................................................... -

Notification - Not

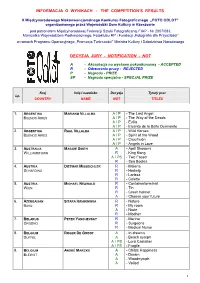

INFORMACJA O WYNIKACH - THE COMPETITION’S RESULTS X Mi ędzynarodowego Niekonwencjonalnego Konkursu Fotograficznego „FOTO ODLOT” organizowanego przez Wojewódzki Dom Kultury w Rzeszowie pod patronatem Mi ędzynarodowej Federacji Sztuki Fotograficznej FIAP - Nr 2007/083, Marszałka Województwa Podkarpackiego, Fotoklubu RP i Fundacji „Fotografia dla Przyszło ści” w ramach Programu Operacyjnego „Promocja Twórczo ści” Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego DECYZJA JURY - NOTIFICATION - NOT A - Akceptacja na wystaw ę pokonkursow ą - ACCEPTED R - Odrzucenie pracy - REJECTED P - Nagroda - PRIZE SP - Nagroda specjalna - SPECJAL PRIZE Kraj Imi ę i nazwisko Decyzja Tytuły prac Lp. COUNTRY NAME NOT TITLES 1. ARGENTINA MARIANO VILLALBA A / P - The Last Angel BUENOS AIRES A / P - The Way of the Deads A / P - Evilia A / P - Elcento de la Bella Durmiente 2. ARGENTINA RAUL VILLALBA A / P - Wild Horses BUENOS AIRES A / P - Spirit of the Wood A / P - Crucifixión A / P - Angels in Love 3. AUSTRALIA MAGGIE SMITH A - April Showers WILLIAMSTOWN R - King Kong A / PS - Two Faced R - Sea Bodies 4. AUSTRIA DIETMAR MISSBICHLER R - Malena SCHÄRDING R - Hedwig R - Larissa R - Colette 5. AUSTRIA MICHAEL NEUWALD R - Containerterminal WIEN R - Tin R - Crash helmet A - Choose your future 6. AZERBAIJAN SITARA IBRAKIMOVA R - Nature BAKU R - My room A - Nude R - Modher 7. BELARUS PETER YANCHEVSKY R - Marina GRODNO R - Surgeons R - Medical Nurse 8. BELGIUM ROGER DE GROOF A - In dreams DUFFEL A - Beach nymph A / PS - Lord Castellan A / PS - Fragile 9. BELGIUM ANDRÉ MARCKX A - Childs Happiness ELEWIJT A - Dream A - Woodnymph A - Veiled 1 10. BELGIUM JOS JANSSENS A - Drowning ELEWIJT A - Hiding A - Nightly Tale A - The shining 11.