3. Opportunity Indicator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STEG Power Transmission Project Environmental and Social Assessment N ON- TECHNICAL S UMMARY

STEG Power Transmission Project Environmental and social assessment N ON- TECHNICAL S UMMARY FÉBRUARY 2016 ORIGINAL Artelia Eau & Environnement RSE International Immeuble Le First 2 avenue Lacassagne 69 425 Lyon Cedex EBRD France DATE : 02 2016 REF : 851 21 59 EBRD - STEG Power Transmission Project Environmental and social assessment Non- technical Summary FEBRUARY 2016 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1.1. INTRODUCTION The Tunisian national energy company STEG (“Société Tunisienne d’Electricité et de Gaz”) is currently implementing the Power Transmission Program of its XIIth National Plan (2011-2016). Under this program, the EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and the EIB (European Investment Bank) are considering contributing to the financing of: a network of high voltage underground power lines in the Tunis-Ariana urban area ; two high-voltage power lines, one in the Nabeul region, the other in the Manouba region; the building or extension of associated electrical substations. The project considered for EBRD/EIB financing consists of 3 sub-components, which are described below. 1.2. SUB-COMPONENT 1: UNDERGROUND POWER LINES IN TUNIS/ARIANA This sub-component comprises a new electrical substation in Chotrana and a series of underground high-voltage power lines: two 225 kV cables, each 10 km in length, from Chotrana to Kram; one 225 kV cable of 12.8 km, from Chotrana to Mnihla; one 90 kV cable of 6.3 km, from “Centre Urbain Nord” substation to Chotrana substation; one 90 kV cable of 8.6 km from « Lac Ouest » substation to Chotrana substation; one 90 kV cable of 2 km from Barthou substation to « Lac Ouest » substation. -

Tunisia Summary Strategic Environmental and Social

PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT: ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT COUNTRY: TUNISIA SUMMARY STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SESA) Project Team: Mr. P. M. FALL, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 Mr. N. SAMB, Consultant Socio-Economist, OITC.2 Mr. A. KIES, Consultant Economist, OITC 2 Mr. M. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. Amadou OUMAROU Regional Director: Mr. Jacob KOLSTER Division Manager: Mr. Abayomi BABALOLA 1 PMIR Summary Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Project Name : ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE MODERNIZATION PROJECT Country : TUNISIA Project Number : P-TN-DB0-013 Department : OITC Division: OITC.2 1 Introduction This report is a summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) of the Road Project Modernization Project 1 for improvement works in terms of upgrading and construction of road structures and primary roads of the Tunisian classified road network. This summary has been prepared in compliance with the procedures and operational policies of the African Development Bank through its Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category 1 projects. The project description and rationale are first presented, followed by the legal and institutional framework in the Republic of Tunisia. A brief description of the main environmental conditions is presented, and then the road programme components are presented by their typology and by Governorate. The summary is based on the projected activities and information contained in the 60 EIAs already prepared. It identifies the key issues relating to significant impacts and the types of measures to mitigate them. It is consistent with the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) developed to that end. -

Décret N° 98-2092 Du 28 Octobre 1998, Fixant La Liste Des Grandes

Décret n° 98-2092 du 28 octobre 1998, fixant la liste des grandes agglomérations urbaines et des zones sensibles qui nécessitent l'élaboration de schémas directeurs d'aménagement (JORT n° 88 du 3 novembre 1998) Le Président de la République, Sur proposition des ministres de l'environnement et de l'aménagement du territoire et de l'équipement et de l'habitat, Vu la loi n° 94-122 du 28 novembre 1994, portant promulgation du code de l'aménagement du territoire et de l'urbanisme et notamment son article 7, Vu l'avis des ministres du développement économique, de l'agriculture et de la culture, Vu l'avis du tribunal administratif, Décrète : Article 1er La liste des grandes agglomérations urbaines qui nécessitent l'élaboration de schémas directeurs d'aménagement est fixée comme suit : 1 - le grand Tunis : les circonscriptions territoriales des gouvernorats de Tunis, Ariana et Ben Arous. 2 - le grand Sousse : les circonscriptions territoriales des communes de Sousse, Hammam- Sousse, M'saken, Kalâa Kebira, Kalâa Sghira, Akouda, Kssibet-Thrayet, Zaouiet Sousse, Ezzouhour, Messaâdine. 3 - le grand Sfax : les circonscriptions territoriales des communes de Sfax, Sakiet Eddaïer, Sakiet Ezzit, El Aïn, Gremda, Chihia, Thyna. 4 - Monastir : la circonscription territoriale du gouvernorat de Monastir. 5 - Bizerte : les circonscriptions territoriales des communes de : Bizerte, Menzel Jemil, Menzel Abderrahmen. 6 - le grand Gabès : les circonscriptions territoriales des communes de grand Gabès, Ghannouch, Chenini-Nahal; El Matouiya, Ouedhref. 7 - Nabeul : les circonscriptions territoriales des communes de Nabeul, Dar Chaâbane El Fehri, Beni Khiar, El Maâmoura, Hammamet. 8 - les agglomérations urbaines des villes de Béja, Jendouba, El Kef, Siliana, Zaghouan, Kairouan, Kasserine, Sidi Bouzid, Mehdia, Gafsa, Tozeur, Kébili, Medenine, Tataouine. -

Plant Natural Resources and Fruit Characteristics of Fig (Ficus Carica L.) Change from Coastal to Continental Areas of Tunisia

E3 Journal of Agricultural Research and Development Vol. 3(2). pp. 022-025, April, 2013 Available online http://www.e3journals.org ISSN: 2276-9897 © E3 Journals 2013 Full Length Research Paper Plant natural resources and fruit characteristics of fig (Ficus carica L.) change from coastal to continental areas of Tunisia Mehdi Trad 1*, Badii Gaaliche 1, Catherine M.G.C.Renard 2 and Messaoud Mars 1 1U.R. Agrobiodiversity, High Agronomic Institute of Chott-Mariem, University of Sousse, 4042 Sousse, Tunisia. 2INRA, Université d’Avignon et des pays du Vaucluse, UMR408 SQPOV, F-84000 Avignon, France. Accepted 24 February, 2013 The fig ( Ficus carica L.) is widely distributed and represents a natural wealth and diversity in all Tunisia. Investigations in the field showed that ‘smyrna’ type, bearing one generation of figs, were predominant in the coast while ‘san pedro’ type, bearing two generations of fruits, is more encountered in the continent. A large array of caprifig trees were counted in coastal ‘Bekalta’, while caprifigs are rare in ‘Djebba’ and are mostly found in wild form. Biodiversity of fig species was corroborated by analysis of the fruit. A wide range of size, shape (round, oblate and oblong) and colour (yellow green, purple green and purple black) was observed in the two areas. Fruits originated from continental zone were larger (59 mm) and heavier (82 g), while fruits from coastal zone were sweetener (18.4%) and tasteful. Comparison of cultivar ‘Zidi’ growing in the two contrasting areas revealed a gain of precocity in fruit ripeness in the coast. However, ‘Zidi’ figs picked from continental ‘Djebba’ were larger, heavier and sweetener than those picked from ‘Bekalta’. -

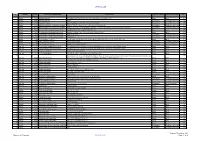

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

I) Sewage Disposal, Lake Bizerte and (II) Sewage Disposal, 6 + 2 Locations in the Medjerda Valley (Phase II

Tunisia: (I) Sewage disposal, Lake Bizerte and (II) Sewage disposal, 6 + 2 locations in the Medjerda valley (Phase II) Ex post evaluation report OECD sector 1402000 / Sewage disposal BMZ project ID I 199365644 – Sewage disposal (SD), Lake Bizerte II 199166075 – SD at 6 + 2 locations in the Medjerda valley (Ph. II) Project executing agency OFFICE NATIONAL DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT (ONAS) Consultant GKW/Pöyry Year of 2009 ex post evaluation report 2009 (2009 random sample) Project appraisal Ex post evaluation (planned) (actual) Start of implementation I Q3 1994 I Q2 1995 II Q3 1993 II Q3 1994 Period of implementation I 40 months I 133 months II 52 months II 116 months Investment costs I EUR 33.3 million I EUR 29.4 million II EUR 78.9 million II EUR 53.4 million Counterpart contribution I EUR 13.3 million I EUR 13.6 million II EUR 25.0 million II EUR 21.6 million Financing, of which Financial I FC/G: EUR 20.0 million I FC/G: EUR 15.8 million Cooperation (FC) funds II FC/L: EUR 37.9 million II FC/G: EUR 31.8 million Other institutions/donors involved I + II Project executing I + II Project executing agency agency Performance rating I: 3 II: 3 • Relevance I: 2 II: 2 • Effectiveness I: 3 II: 3 • Efficiency I: 3 II: 3 • Overarching developmental impact I: 2 II: 2 • Sustainability I: 3 II: 3 Brief description, overall objective and project objectives with indicators I: This project comprised the initial expansion of the sewage treatment plant (STP) west of Bizerte and the expansion and repair of the sewage collection systems in Bizerte, in Zarzouna (a suburb of Bizerte), and in the towns of Menzel Jemil and Menzel Abderrahman (in the Greater Bizerte area), the aim being to dispose of domestic sewage and commercial effluent in an environmentally sound manner (the project objective). -

Quarterly Report Year Three, Quarter Two – January 1, 2021 – March 31, 2021

Ma3an Quarterly Report Year Three, Quarter Two – January 1, 2021 – March 31, 2021 Submission Date: April 30, 2021 Agreement Number: 72066418CA00001 Activity Start Date and End Date: SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 to AUGUST 31, 2023 AOR Name: Hind Houas Submitted by: Patrick O’Mahony, Chief of Party FHI360 Tanit Business Center, Ave de la Fleurs de Lys, Lac 2 1053 Tunis, Tunisia Tel: (+216) 58 52 56 20 Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. July 2008 1 CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 1 Project Overview .................................................................................................... 2 Ma3an’s Purpose ................................................................................................................................. 2 Context .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Year 3 Q2 Results ................................................................................................... 4 OBJECTIVE 1: Youth are equipped with skills and engaged in civic actions with local actors to address their communities’ needs. .................................................................................. 4 OBJECTIVE 2: Tunisian capabilities to prevent -

Rapport Annuel 2013

Rapport Annuel 2013 www.steg.com.tn Siège Social 38, Rue Kamel Attaturk - 1080 Tunis B.P190 Tél. : (216) 71 341 311 Fax : (216) 71 341 401 / 71 349 981 / 71 330 174 E-mail : [email protected] Rapport Annuel 2013 SOMMAIRE COMPOSITION DU CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION DE LA STEG 4 ORGANIGRAMME GENERAL DE LA STEG 5 INTRODUCTION 6-7 FAITS SAILLANTS 8-10 BILANS ET CHIFFRES CLES 11-16 L’ELECTRICITE 17- 34 LE GAZ 35-42 LES RESSOURCES HUMAINES 43-50 LE MANAGEMENT 51-56 LA MAITRISE DE LA TECHNOLOGIE 57-60 LES FINANCES 61-66 LES ETATS FINANCIERS 67-71 3 SOCIÉTÉ TUNISienne de l’ELECTRICITÉ ET DU GAZ Rapport Annuel 2013 COMPOSITION DU CONSEIL PRESIDENT-DIRECTEUR GENERAL M. RACHID BEN DALY HASSEN ADMINISTRATEURS REPRESENTANT L’ETAT MM. FARES BESROUR ABDELMELEK SAADAOUI GHAZI CHERIF SAHBI BOUCHAREB KHALIL JEMMALI Mmes. SEJIAA OUALHA NEILA BEN KHELIFA NAWEL BEN ROMDHANE DHERIF ADMINISTRATEURS REPRESENTANT LE PERSONNEL MM. MUSTAPHA TAIEB ABDELKADER JELASSI CONTROLEUR D’ETAT M. MOHAMED LASSAAD MRABET INVITEE Mme. SALWA SGHAIER 4 SOCIÉTÉ TUNISienne de l’ELECTRICITÉ ET DU GAZ Rapport Annuel 2013 ORGANIGRAMME GÉNÉRAL CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION DIRECTION GENERALE DIRECT IO N D E L A M A I T R ISE SECRETARIAT PERMANENT DE DE L A TE CHN O L OG I E LA COMMISSION DES MARCHES PRESIDENT- DIRECTEUR Mme Wided MAALEL GENERAL Ali BEN ABDALLAH Rachid BEN DALY DEPARTEMENT DES SERVICES GROUPE DES ETUDES HASSEN CENTRAUX STRATEGIQUES Ibrahim GHEZAIEL Abdelaziz GHARBIA DIRECTEUR GENERAL DEPARTEMENT DE LA ADJOINT COMMUNICATION ET DE LA Samir CHAABOUNI Mohamed Nejib HELLAL COOPERATION -

Mauritania and in Lebanon by the American University Administration

Arab Trade Union Confederation (ATUC) A special report on the most important trade union rights and freedoms violations recorded in the Arab region during the COVID-19 pandemic period October 2020 2 Introduction The epidemic in the Arab region has not been limited to the Corona pandemic, but there appeared another epidemic that has been more deadly to humans. It is the persecution of workers under the pretext of protection measurements against the spread of the virus. The International Trade Union Confederation of Global Rights Index indicated that the year 2020 is the worst in the past seven years in terms of blackmailing workers and violating their rights. The seventh edition of the ITUC Global Rights Index documents labour rights violations across 144 countries around the world, especially after the Corona pandemic, which has suspended many workers from their work during the current year. The Middle East and North Africa have been considered the worst regions in the world for workers for seven consecutive years due to the on-going insecurity and conflict in Palestine, Syria, Yemen and Libya. Such regions have also been the most regressive for workers’ representation and union rights. "In light of the emerging coronavirus (Covid-19), some countries have developed anti-worker measures and practices during the period of precautionary measures to confront the outbreak of the pandemic," said Sharan Burrow, The Secretary-General of the International Trade Union Confederation. Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, Egypt, Honduras, India, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Turkey and Zimbabwe turned out to be the ten worst countries for working people in 2020 among other 144 countries that have been examined. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 33397-TN PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF EUR 3 1.O MILLION (US38.03 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE SOCIbTE NATIONALE D’EXPLOITATION ET DE DISTRIBUTIONDES EAUX (NATIONAL PUBLIC WATER SUPPLY UTILITY) WITH THE GUARANTEE OF THE REPUBLIC OF TUNISIA FOR AN Public Disclosure Authorized URBAN WATER SUPPLY PROJECT October 13,2005 FINANCE, PRIVATE SECTOR AND INFRASTRUCTUREGROUP (MNSIF) MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA (MNA) This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized Bank 11 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective May 11,2005) Currency Unit = Tunisian Dinar (TND) 1.258 TND = US$ 1 US$O.795 = TND 1 1 US$ = EUR 0.8 106 (Aug 3 1,2005) FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS DGRE Direction GknCrale des Ressources en Eaux (Water Resources Department) DSCR Debt Service Coverage Ratio EMP Environmental Management Plan ERP Entreprise Resource Planning GEG Ghdir El Gollah (location ofTunis water treatment plant) GIS Geographic Information System GOT Government ofTunisia IRR Internal Rate ofReturn LLCR Long Term Liability Coverage Ratio MAWR Ministry ofAgriculture and Water Resources MDG Millenium Development Goals MDT Millions ofTunisian Dinars MENA Middle East and North Africa MESD Ministry ofEnvironment and -

Initiative Pour Le Développement Régional Renforcer Les Approches Participatives Du Développement Régional En Tunisie

Mise en oeuvre par: Initiative pour le Développement Régional Renforcer les approches participatives du développement régional en Tunisie Le défi Nom du projet Initiative pour le Développement Régional Mandataire Ministère fédéral allemand de la Coopération La Tunisie est marquée par d’énormes écarts en matière de économique et du Développement (BMZ) développement régional. Les activités économiques se Régions Huit gouvernorats: Médenine, Kasserine, Kef, Sidi concentrent majoritairement sur Tunis, la capitale, et les régions d‘intervention Bouzid, Béja, Siliana, Jendouba, Kairouan côtières du nord et nord-est. Les régions rurales de l’intérieur Organisme Ministère du Développement, de l’Investissement et sont majoritairement coupées de ces activités. Le taux de partenaire de la Coopération Internationale (MDICI) chômage s’élevait ainsi, en 2014, à 23 % en moyenne dans les Partenaires Direction Générale de coordination et de suivi de régions de l’intérieur, alors qu’il était de 10 % dans les régions nationaux/ l’exécution des projets publics et des programmes régionaux régionaux (DGCSEPPPR), Directions de côtières. La Tunisie souffre également d’un accès inégal aux Développement Régional (DDR), représentants services publics. C’est l’une des principales raisons pour laquelle sectoriels de l’administration régionale, associations de la société civile des troubles sociaux éclatent à intervalle régulier dans les régions défavorisées du pays. Durée 2015-2021 Le gouvernement a identifié comme principale cause de ce déséquilibre la forte centralisation de l’État au cours des Les acteurs régionaux ne disposent cependant pas encore des dernières décennies. Ainsi, la planification au niveau local n’a pas capacités et de l’expérience suffisante pour la mise en œuvre de tenu compte des besoins de la population, et la mise en œuvre de plans de développement.