(Lodoicea Maldivica (JF Gmel.) Pers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Vallée de Mai Nature Reserve - 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment Vallée de Mai Nature Reserve 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment SITE INFORMATION Country: Seychelles Inscribed in: 1983 Criteria: (vii) (viii) (ix) (x) In the heart of the small island of Praslin, the reserve has the vestiges of a natural palm forest preserved in almost its original state. The famouscoco de mer, from a palm-tree once believed to grow in the depths of the sea, is the largest seed in the plant kingdom. © UNESCO SUMMARY 2020 Conservation Outlook Finalised on 01 Dec 2020 GOOD WITH SOME CONCERNS The protection and management of Vallée de Mai Nature Reserve is generally effective and is supported by a national legal framework, although there is a lack of a national protected area system. The management authority is very competent and is effectively implementing science-based programs and outreach and education schemes. However, the future of the site’s key value, the coco de mer palm, is still under threat from illegal collection and over-exploitation for its nuts and kernel. The site's management has reduced both commercial harvesting and illegal collection of nuts based on scientific research, although the conservation impacts of these requires further assessment. The National Government and the managing agency are implementing targeted conservation measures and aim to tighten law and legislation to protect the species, which include an increase in penalty for poaching of coco de mer nuts. Current priorities for the Nature Reserve include continuation and expansion of the outreach and education programme; promoting an increase in the size and connectivity of Vallée de Mai within the Praslin Island landscape, with a legally designated buffer zone; increasing anti-poaching; and continuing to control the harvesting of coco de mer seeds while expanding a program of replanting seedlings. -

Rj FLORIDA PLANT IMMIGRANTS

rj FLORIDA PLANT IMMIGRANTS OCCASIONAL PAPER No. 15 FAIRCHILD TROPICAL GARDEN THE INTRODUCTION OF THE BORASSUS PALMS INTO FLORIDA DAVID FAIRCHILD COCONUT GROVE, FLORIDA May 15, 1945 r Fruits and male flower cluster of the Borassus palm of West Africa (Borassus ethiopum). The growers of this palm and its close relative in Ceylon are fond of the sweetish fruit-flesh and like the mango eaters, where stringy seedlings are grown, they suck the pulp out from the fibers and enjoy its sweetish flavor. The male flower spikes were taken from another palm; a male palm. Bathurst, Gambia, Allison V. Armour Expedition, 1927. THE INTRODUCTION OF THE BORASSUS PALMS INTO FLORIDA DAVID FAIRCHILD JL HE Borassus palms deserve to be known by feet across and ten feet long and their fruits the residents of South Florida for they are land- are a third the size of average coconuts with scape trees which may someday I trust add a edible pulp and with kernels which are much striking tropical note to the parks and drive- appreciated by those who live where they are ways of this garden paradise. common. They are outstanding palms; covering vast areas of Continental India, great stretches They attain to great size; a hundred feet in in East and West Africa and in Java, Bali and height and seven feet through at the ground. Timor and other islands of the Malay Archi- Their massive fan-shaped leaves are often six pelago. &:••§:• A glade between groups of tall Palmyra palms in Northern Ceylon. The young palms are coming up through the sandy soil where the seeds were scattered over the ground and covered lightly months before. -

Status, Distribution and Recommendations for Monitoring of the Seychelles Black Parrot Coracopsis (Nigra) Barklyi

Status, distribution and recommendations for monitoring of the Seychelles black parrot Coracopsis (nigra) barklyi A. REULEAUX,N.BUNBURY,P.VILLARD and M . W ALTERT Abstract The Seychelles black parrot Coracopsis (nigra) species (Snyder et al., 2000). Their conservation, however, barklyi, endemic to the Seychelles islands, is the only remains a significant challenge. Almost 30% of the c. 330 surviving parrot on the archipelago. Although originally parrot species are threatened (compared to 13% of all birds, classified as a subspecies of the lesser vasa parrot Coracopsis Hoffmann et al., 2010), primarily because of habitat nigra evidence now indicates that the Seychelles population destruction or capture for the pet trade (Snyder et al., may be a distinct species, in which case its conservation 2000), and the Psittacidae is the avian family with the status also requires reassessment. Here, we address the highest number (both relative and absolute) of taxa on status of the C. (n.) barklyi population on the islands of its the IUCN Red List (Collar, 2000). Twelve parrot species are current and likely historical range, Praslin and Curieuse, known to have become extinct since 1600 and historical assess the effect of habitat type on relative abundance, and evidence suggests that others have also been lost identify the most appropriate point count duration for (Stattersfield, 1988). Ten of these documented extinctions monitoring the population. We conducted point count were endemic island species. Such species have typically distance sampling at 268 locations using habitat type as a restricted ranges and population sizes, which make them covariate in the modelling of the detection function. -

Vallee De Mai Nature Reserve Seychelles

VALLEE DE MAI NATURE RESERVE SEYCHELLES The scenically superlative palm forest of the Vallée de Mai is a living museum of a flora that developed before the evolution of more advanced plant families. It also supports one of the three main areas of coco-de-mer forest still remaining, a tree which has the largest of all plant seeds. The valley is also the only place where all six palm species endemic to the Seychelles are found together. The valley’s flora and fauna is rich with many endemic and several threatened species. COUNTRY Seychelles NAME Vallée de Mai Nature Reserve NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 1983: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii, viii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following Statement of Outstanding Universal Value at the time of inscription Brief Synthesis Located on the granitic island of Praslin, the Vallée de Mai is a 19.5 ha area of palm forest which remains largely unchanged since prehistoric times. Dominating the landscape is the world's largest population of endemic coco-de- mer, a flagship species of global significance as the bearer of the largest seed in the plant kingdom. The forest is also home to five other endemic palms and many endemic fauna species. The property is a scenically attractive area with a distinctive natural beauty. Criterion (vii): The property contains a scenic mature palm forest. The natural formations of the palm forests are of aesthetic appeal with dappled sunlight and a spectrum of green, red and brown palm fronds. -

Seychelles Birding Trip Report

Seychelles birding trip report From December 26 (2008) to January 6 (2009) we spend our Christmas holidays on the Seychelles. Curiosity was the main driving force to visit this archipelago in the Indian ocean. Our goals were to see various islands, relax on the wonderful beaches, enjoy the local cuisine, snorkel the coral reefs, and last but not least do some birdwatching. We tried to see and photograph as many as possible endemics and tropical sea birds. December or January is definitely not the best time to visit the Seychelles because it’s the rainy season, and it’s outside the breeding season, making it hard to see some bird species or good numbers. Indeed we had a few days with a lot of rain and other days with very cloudy skies and wind. About half of the time we had marvelous sunny beach weather. Day time temperature usually was around 30°C. With regard to birding the preparation consisted of reading a number of trip reports from internet (see: www.travellingbirder.com) and the ‘Birds of the Seychelles’ by Skerrett et al. (2001). To see all endemics of the northern island of the Seychelles (the so-called granitic group) at least 4 islands need to be visit: Mahe, Praslin, La Digue, and Cousin. The first three island can be visited at any time. Tourist day trips to Cousin are usually organized on Tuesdays and Fridays and departure from Praslin, but as it turned out not on January 2, the day we were planning to go there. A fisherman was willing to take us to Cousin on another date in his small boat for 175 Euro. -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

1 7 an Identification Key to the Geckos of the Seychelles

HERPETOLOGICAL JOURNAL. Vol. I. pp. 17-19 (19X5l 17 AN IDENTIFICATION KEY TO THE GECKOS OF THE SEYCHELLES, WITH BRIEF NOTES ON THEIR DISTRIBUTIONS AND HABITS ANDREW S. GARDNER Department of Zoology, University of Aberdren. Ti/lydrone Avenue, Aberdeen AB9 2TN. U. K. Present addresses: The Calton Laboratory. Department of Genetics and Biomet IT, Universif.I' Co/legr London. Wo/f�·on !-louse, 4 Stephenson Wa r London NWI 21-11'.. U.K. (A ccepted 24. /0. 84) INTRODUCTION 4. Scales on chest and at least anterior of belly keeled. Underside white. Phe!suma astriata The Republic of Seychelles, lying in the western Tornier. 5. Indian Ocean consists of a group of mountainous, granitic islands, and a large number of outlying coral Scales on chest and belly not keeled. 6. atolls and sand cays, distributed over 400,000 km2 of sea. There are over a hundred islands, ranging in size 5. Subcaudal scales keeled and not transversely from Mahe, at 148 km2 to islands little more than enlarged in original tails. Ground colour of emergent rocks. A total of eighteen species of lizard, rump and tail usually bright blue, and of from three families are recorded from the Seychelles nanks, green. Tail unmarked or spotted with (Gardner, 1984). The best represented family is the red. Red transverse neck bars often reduced or Gekkonidae with eleven species, fo ur of which are absent. Phe/suma astriata astriata Tornier i endemic to the islands. The identification key 90 1. presented here should enable interested naturalists to Subcaudal scales unkeeled and transversely identify any gecko encountered in the Seychelles to the enlarged in original tails. -

Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae

horticulturae Review Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae Diego Gutiérrez del Pozo 1, José Javier Martín-Gómez 2 , Ángel Tocino 3 and Emilio Cervantes 2,* 1 Departamento de Conservación y Manejo de Vida Silvestre (CYMVIS), Universidad Estatal Amazónica (UEA), Carretera Tena a Puyo Km. 44, Napo EC-150950, Ecuador; [email protected] 2 IRNASA-CSIC, Cordel de Merinas 40, E-37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Matemáticas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Salamanca, Plaza de la Merced 1–4, 37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-923219606 Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 2 October 2020; Published: 7 October 2020 Abstract: Fruit and seed shape are important characteristics in taxonomy providing information on ecological, nutritional, and developmental aspects, but their application requires quantification. We propose a method for seed shape quantification based on the comparison of the bi-dimensional images of the seeds with geometric figures. J index is the percent of similarity of a seed image with a figure taken as a model. Models in shape quantification include geometrical figures (circle, ellipse, oval ::: ) and their derivatives, as well as other figures obtained as geometric representations of algebraic equations. The analysis is based on three sources: Published work, images available on the Internet, and seeds collected or stored in our collections. Some of the models here described are applied for the first time in seed morphology, like the superellipses, a group of bidimensional figures that represent well seed shape in species of the Calamoideae and Phoenix canariensis Hort. ex Chabaud. -

1 Ornamental Palms

1 Ornamental Palms: Biology and Horticulture T.K. Broschat and M.L. Elliott Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center University of Florida, Davie, FL 33314, USA D.R. Hodel University of California Cooperative Extension Alhambra, CA 91801, USA ABSTRACT Ornamental palms are important components of tropical, subtropical, and even warm temperate climate landscapes. In colder climates, they are important interiorscape plants and are often a focal point in malls, businesses, and other public areas. As arborescent monocots, palms have a unique morphology and this greatly influences their cultural requirements. Ornamental palms are over- whelmingly seed propagated, with seeds of most species germinating slowly and being intolerant of prolonged storage or cold temperatures. They generally do not have dormancy requirements, but do require high temperatures (30–35°C) for optimum germination. Palms are usually grown in containers prior to trans- planting into a field nursery or landscape. Because of their adventitious root system, large field-grown specimen palms can easily be transplanted. In the landscape, palm health and quality are greatly affected by nutritional deficien- cies, which can reduce their aesthetic value, growth rate, or even cause death. Palm life canCOPYRIGHTED also be shortened by a number of MATERIAL diseases or insect pests, some of which are lethal, have no controls, or have wide host ranges. With the increasing use of palms in the landscape, pathogens and insect pests have moved with the Horticultural Reviews, Volume 42, First Edition. Edited by Jules Janick. 2014 Wiley-Blackwell. Published 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1 2 T.K. BROSCHAT, D.R. HODEL, AND M.L. -

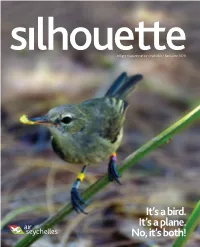

It's a Bird. It's a Plane. No, It's Both!

HM Silhouette Cover_Apr2019-Approved.pdf 1 08/03/2019 16:41 Inflight magazine of Air Seychelles • April-June 2020 It’s a bird. It’s a plane. No, it’s both! 9405 EIDC_Silhou_IBC 3/5/20 8:48 AM Page 5 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Composite [ CEO’S WELCOME ] Dear Guests, Welcome aboard! As you are probably aware, the aviation industry globally is under considerable pressure over the issue of carbon emissions and its impact on climate change. At Air Seychelles we are indeed proud of the contribution we are making towards sustainable development. Following the successful delivery of our second Airbus A320neo aircraft, Pti Merl Dezil in March 2020, I am pleased to announce that Air Seychelles is now operating the youngest jet fleet in the Indian Ocean. Performing to standard, the new engine option aircraft is currently on average generating 20% fuel savings per flight and 50% reduced noise footprint. This amazing performance cannot go unnoticed and we remain committed to further implement ecological measures across our business. Apart from keeping Seychelles connected through air access, Air Seychelles also provides ground handling services to all customer airlines operating at the Seychelles International Airport. Following an upsurge in the number of carriers coming into the Seychelles, in 2019 we surpassed the 1 million passenger threshold handled at the airport, recording an overall growth of 5% increase in arrival and departures. Combining both inbound and outbound travel including the domestic network, Air Seychelles alone contributed a total of 414,088 passengers after having operated 1,983 flights. -

A Phylogeny and Revised Classification of Squamata, Including 4161 Species of Lizards and Snakes

BMC Evolutionary Biology This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:93 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-93 Robert Alexander Pyron ([email protected]) Frank T Burbrink ([email protected]) John J Wiens ([email protected]) ISSN 1471-2148 Article type Research article Submission date 30 January 2013 Acceptance date 19 March 2013 Publication date 29 April 2013 Article URL http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/93 Like all articles in BMC journals, this peer-reviewed article can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright notice below). Articles in BMC journals are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central. For information about publishing your research in BMC journals or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/ © 2013 Pyron et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes Robert Alexander Pyron 1* * Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Frank T Burbrink 2,3 Email: [email protected] John J Wiens 4 Email: [email protected] 1 Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G St. -

PS 20 4 Nov 08.Qxd

I N THIS I SSUE www.psittascene.org Hope for Thick-billed Parrots Reintroduction of the Kuhl's Lory November 2008 Volume 20 Number 4 PPssiittttaa from the director SWSorld Pccarrot Teerust nnee Glanmor House, Hayle, Cornwall, TR27 4HB, UK. or years we've planned to run a WPT member survey to www.parrots.org learn more about who you are, what you think we're doing Fright, and where you think we could improve our work. We contents deeply appreciate so many of you taking the time to provide us 2 From the Director with such valuable feedback. It has been a pleasure reading over all the responses we received both by mail and online. 4 Rays of Hope Thick-billed Parrot Of course those of us who work for the Trust - either as volunteers 8 An Island Endemic Kuhl’s Lory or staff - are committed to the conservation and welfare of parrots 12 Parrots in Paradise … indeed, just getting the job done is very rewarding in its own Seychelles Black Parrot right. But reviewing the survey results was especially delightful 16 Of Parrots and People because you were so enthusiastic about our work, about PsittaScene , Book Review and the Trust in general. We learned a great deal just as we had 17 Species Profile hoped. We'll take all your comments to heart and incorporate your Lilac-tailed Parrotlet suggestions as we find opportunities. You may see some of your 18 PsittaNews PsittaScene ideas in this issue and others we will work in over time. 19 WPT Contacts Among the outstanding results was your enthusiasm for recommending 20 Parrots in the Wild: Kuhl’s Lory the Trust to others.