José Mourinho “Please Don't Call Me Arrogant, but I'm European

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kits Version

COUNTER ATTACK version 1.4 These representations are 100% unofficial KITS THAT COME WITH THE GAME ENGLAND ITALY SCOTLAND OTHER EUROPEAN TEAMS 021 004 022 118 001 002 040 041 002 SOON... 061 042 003 057 058 119 059 028 006 095 096 099 042 9 7 4 5 8 10 6 2 7 4 6 5 7 3 4 9 3 9 11 2 6 JUVENTUS AJAX YELLOW GK BLUE GK NEWCASTLE ARSENAL WEST HAM BOURNEMOUTH BRIGHTON CHELSEA CRYSTAL PALACE AC MILAN ATALANTA/ BOLOGNA BRESCIA CAGLIARI/ FIORENTINA ABERDEEN CELTIC DUNDEE UTD HAMILTON HEARTS OLYMPIACOS AEK ATHENS PANATHINAIKOS PAOK CLUB BRUGGE ANDERLECHT ST MIRREN ASTON VILLA EVERTON INTER GENOA BURNLEY 023 024 007 025 INCLUDED 026 SOON... INCLUDED 043 007 102 SOON... 060 061 118 062 063 097 003 098 021 128 129 CURRENTLY AVAILABLE individually 5 5 2 3 9 10 5 7 10 10 4 7 5 10 9 3 8 in the counter attack store 7 4 LEICESTER LIVERPOOL MAN CITY MAN UTD NEWCASTLE NORWICH HELLAS JUVENTUS JUVENTUS LAZIO LECCE PARMA HIBS ICT KILMARNOCK LIVINGSTON MOTHERWELL SPORTING CP BENFICA FC PORTO / BRAGA BOAVISTA DUKLA PRAGUE 001 002 003 004 005 VERONA CLASSIC / MODERN NAPOLI IFK GOTHENBURG UDINESE 027 028 029 030 031 120 044 SOON... 045 046 059 091 064 SOON 001 INCLUDED 094 100 101 004 036 130 131 4 10 11 4 3 CHELSEA BARCELONA BENFICA WEST HAM RIVER PLATE 2 3 4 11 11 3 7 7 8 5 7 4 5 11 4 8 11 SCHALKE INVERNESS LIVERPOOL ASTON VILLA RANGERS C.PALACE ABERDEEN BURNLEY SHEFF UTD SOUTHAMPTON TOTTENHAM WATFORD WOLVES BRADFORD ROMA SPAL SAMPDORIA SASSUOLO TORINO PALERMO RANGERS ROSS CO. -

Abcd Elena Fernández Aréizaga Curriculum Vitae

abcd Elena Fern´andezAr´eizaga Curriculum Vitae Diciembre 2019 1 1 Datos generales y situaci´onprofesional 2 1. Datos generales y situaci´onprofesional Apellidos: Fern´andezAr´eizaga Nombre: Elena DNI: 15915657W Fecha de nacimiento: 04/07/1956 Organismo: Universidad de C´adiz(UCA) Centro: Facultad de Ciencias Depto: Estad´ısticai Investigaci´oOperativa (EIO) Direccion´ postal: Pol´ıgonoR´ıoSan Pedro 11510 Puerto Real. Telefono:´ + 34 956 01 2783 Fax: + 34 956 01 6228 Correo electronico:´ [email protected] Categoria profesional: Catedr´aticode Universidad. (Fecha de inicio: 23-03-2007) Situacion´ administrativa: Plantilla Dedicacion:´ Tiempo completo Researcher ID: E-1799-2012 Codigo´ Orcid: 0000-0003-4714-0257 Especializacion´ (Codigos´ UNESCO): 1207/1203.26. (AMS 2010) 90C57, 90C10 L´ıneas de investigacion:´ Optimizaci´ondiscreta. Problemas discretos en redes. An´alisisde localizaci´on. Dise~node rutas de veh´ıculos. 1 Datos generales y situaci´onprofesional 3 Formaci´onacad´emica Titulacion´ Superior Centro Fecha Licenciatura de Matem´aticas Fac. Ciencias - Univ. Zaragoza 1979 Grado de Lic. Matem´aticas Fac. Ciencias - Univ. Valencia 1985 Doctorado Centro Fecha Doctora en Inform´atica Universitat Polit`ecnicade Catalunya 1988 Actividades anteriores de car´acteracad´emico Puesto Institucion´ Fechas Catedr´aticaUniversidad Dpt EIO - UPC 23-03-07 / 10-01-19 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) Prof. Titular Universidad Dpt EIO - UPC 01-02-89/ 22-03-07 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) Prof. Asociado a Tiempo Completo Fac. Inform`atica.Barcelona. UPC 01-10-87/ 31-01-89 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) Prof. Colaboradora Fac. Inform`atica.Barcelona. UPC 01-12-84 / 30-09-87 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) Prof. Colaboradora Fac. Inform´atica.San Sebasti´an 01-10-83/ 30-11-84 (dedicaci´onexclusiva) U. -

University of Peloponnese Faculty of Human Movement

UNIVERSITY OF PELOPONNESE FACULTY OF HUMAN MOVEMENT AND QUALITY OF LIFE DEPARTMENT OF SPORTS MANAGEMENT RESEARCH ON BASKETBALL TRENDS AND EVOLUTION METHODOLOGIES IN COUNTRIES WITH LOW POPULARITY OF THE SPORT: THE CASE OF PORTUGAL AND THE COMPAL AIR (3V3) SCHOOL TOURNAMENT by Panagiotis Chatziavgoustidis, BSc. A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Sports Organization and Management of University of Peloponnese in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Master of Sciences Degree Sparta, 2015 1 Copyright © Χατζηαυγουστίδης Παναγιώτης, 2015 Με επιφύλαξη κάθε δικαιώματος. All rights reserved. Απαγορεύεται η αντιγραφή, αποθήκευση και διανομή της παρούσας εργασίας, εξ ολοκλήρου ή τμήματος αυτής, για εμπορικό σκοπό. Επιτρέπεται η ανατύπωση, αποθήκευση και διανομή για σκοπό μη κερδοσκοπικό, εκπαιδευτικής ή ερευνητικής φύσης, υπό την προϋπόθεση να αναφέρεται η πηγή προέλευσης και να διατηρείται το παρόν μήνυμα. Ερωτήματα που αφορούν τη χρήση της εργασίας για κερδοσκοπικό σκοπό πρέπει να απευθύνονται προς τον συγγραφέα. Οι απόψεις και τα συμπεράσματα που περιέχονται σε αυτό το έγγραφο εκφράζουν τον συγγραφέα και δεν πρέπει να ερμηνευθεί ότι αντιπροσωπεύουν τις επίσημες θέσεις του Πανεπιστημίου Πελοποννήσου του Τμήματος Οργάνωσης και Διαχείρισης Αθλητισμού 2 ABSTRACT Panagiotis Chatziavgoustidis: Research on basketball trends and evolution methodologies in countries with low popularity of the sport: Τhe case of Portugal and the Compal Air (3v3) school tournament (With the supervision of Dr. Athanasios Kriemadis, Associate Professor) The scope of the current thesis is to analyze and understand the reason why basketball is a sport of low popularity in Portugal. Moreover, already applied strategies will be observed and ideas that could provide a greater level of help to the Portuguese Basketball Federation will be given. -

As Fontes De Informação No Porto Canal- O Caso Do Jornal Diário Ana Isabel Moreira Moura

MESTRADO EM CIÊNCIAS DA COMUNICAÇÃO VARIANTE DE ESTUDOS DE MEDIA E JORNALISMO As fontes de informação no Porto Canal- o caso do Jornal Diário Ana Isabel Moreira Moura M 2019 Ana Isabel Moreira Moura As fontes de informação do Porto Canal- o caso do Jornal Diário Relatório de estágio realizado no âmbito do Mestrado em Ciências da Comunicação, orientado pelo Professor Doutor Paulo Frias da Costa Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto setembro de 2019 As Fontes de Informação do Porto Canal- o caso do Jornal Diário Ana Isabel Moreira Moura Relatório de estágio realizado no âmbito do Mestrado em Ciências da Comunicação, orientado pelo professor Doutor Paulo Frias da Costa Membros do Júri Professor Doutor Paulo Frias da Costa Faculdade de Letras- Universidade do Porto Professor Doutor Pedro Costa Faculdade de Engenharia- Universidade do Porto Professor Doutor Hélder Bastos Faculdade de Letras- Universidade do Porto Classificação obtida: 16 valores Sumário Declaração de honra ....................................................................................................... 10 Agradecimento………………………………………………………………………..….9 Resumo…………………………………………………………………………………12 0 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………13 Índice de gráficos circulares ........................................................................................... 12 Introdução ....................................................................................................................... 15 Capítulo 1 – O estágio ................................................................................................... -

NBA MLB NFL NHL MLS WNBA American Athletic

Facilities That Have the AlterG® ® Anti-Gravity Treadmill Texas Rangers LA Galaxy NBA Toronto Blue Jays (2) Minnesota United Atlanta Hawks (2) Washington Nationals (2) New York City FC Brooklyn Nets New York Red Bulls Boston Celtics Orlando City SC Charlotte Hornets (2) NFL Real Salt Lake Chicago Bulls Atlanta Falcons San Jose Earthquakes Cleveland Cavaliers Sporting KC Denver Nuggets Arizona Cardinals (2) Detroit Pistons Baltimore Ravens Golden State Warriors Buffalo Bills WNBA Houston Rockets Carolina Panthers Indiana Pacers Chicago Bears New York Liberty Los Angeles Lakers Cincinnati Bengals Los Angeles Clippers Cleveland Browns COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY Memphis Grizzlies Dallas Cowboys PHYSICAL THERAPY (3) PROGRAMS Miami Heat Denver Broncos Milwaukee Bucks (2) Detroit Lions Florida Gulf Coast University Minnesota Timberwolves Green Bay Packers Chapman University (2) New York Knicks Houston Texans Northern Arizona University New Orleans Pelicans Indianapolis Colts Marquette University Oklahoma City Thunder Jacksonville Jaguars University of Southern California Orlando Magic Kansas City Chiefs (2) University of Delaware Philadelphia 76ers Los Angeles Rams Samuel Merritt University Phoenix Suns (2) Miami Dolphins Georgia Regents University Hardin- Portland Trailblazers Sacramento Minnesota Vikings Simmons University Kings New England Patriots High Point University San Antonio Spurs New Orleans Saints Long Beach State University Utah Jazz New York Giants Chapman University (2) Washington Wizards New York Jets University of Texas at Arlington- -

Relatório E Contas Da Sporting Sad Época 2007 » 2008

RELATÓRIO E CONTAS DA SPORTING SAD ÉPOCA 2007 » 2008 RELATÓRIO E CONTAS DA SPORTING SAD ÉPOCA 2007 » 2008 » 01 Relatório do Conselho de Administração e Anexos » 02 Demonstrações Financeiras a 30 de Junho de 2007 e 30 de Julho de 2008 » 03 Certificação Legal das Contas e Relatório de Auditoria » 04 Relatório e Parecer do Conselho Fiscal sobre as contas referentes a 30 de Junho de 2008 RELATÓRIO E CONTAS DA SPORTING SAD ÉPOCA 2007.08 P »01 Relatório do Conselho de Administração e Anexos » RELATÓRIO DO CONSELHO DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO E ANEXOS Senhores Accionistas, Em cumprimento da legislação em vigor, vimos submeter à apreciação de V. Exas. o Relatório do Conselho de Administração, o Balanço e a Demonstração dos Resultados e respectivos anexos reportados ao exercício de 2007/08, que compreende o período de 1 de Julho a 30 de Junho de 2008. A Sociedade apresenta pela primeira vez as suas demonstrações financeiras anuais em conformidade com as Normas Internacionais de Relato Financeiro (IFRS) emitidas pelo In- ternational Accounting Standard Board e adoptadas pela União Europeia. Alguns dos ajustamentos de transição IFRS adoptados tiveram impacto substancial na situ- ação patrimonial e financeira da Sociedade, sobretudo o da anulação da mais-valia decor- rente da venda da participação da DE- Desporto e Espectáculo, SA ocorrida no exercício 2004/05 e consequente deferimento da receita ao longo dos exercícios de 2008/09 a 2018/19, tema que será retomado e explicado pormenorizadamente adiante. P I - ASPECTOS RELEVANTES DA ACTIVIDADE DA SOCIEDADE 1. Actividade Desportiva A época desportiva de 2007-2008, em termos de resultados do Futebol Profissional, ficou marcada pelos seguintes factos: » Conquista da Taça de Portugal, que aconteceu pelo segundo ano consecutivo; » Conquista da Supertaça Cândido de Oliveira, que aconteceu também por dois consecuti- vos; » Apuramento directo, pela terceira vez consecutiva, para a Liga dos Campeões; » Segundo lugar na Primeira Liga, o que também veio a verificar-se pela terceira vez con- secutiva. -

Professional Coach: the Link Between Science and Media

Sport Science Review, vol.Sport XXV, Science No. Review, 1-2, May vol. XXV,2016 no. 1-2, 2016, 73 - 84 DOI: 10.1515/ssr-2016-0004 Professional Coach: The Link between Science and Media Boris ,BLUMENSTEIN1 • Iris, ORBACH2 port science and sport media give special attention to professional Scoaches from individual and team sport. However, there is not a lot of knowledge on those two approaches: Science and media. Therefore, the purpose of this article was to present sport science approach oriented on research, and sport media approach based on description of “coach life stories”. In this article we describe five cases of individual and team coaches. Similarities and difference in these two approaches are discussed. Key words: Science, Media, Professional Coach 1 Ribstein Center for Sport Medicine Sciences and Research, Wingate Institute for Physical Education and Sport, Israel 2 Givat Washington Academic College, Israel ISSN: (print) 2066-8732/(online) 2069-7244 73 © 2016 • National Institute for Sport Research • Bucharest, Romania Coach: Science And Media Professional Coach: The Link between Science and Media Modern competitive sport, including Olympic Games, is considered as a professional area, being affected by science approaches and popular media coverage. When analyzing athlete’s achievement it can be seen that the coach takes an essential role in helping athletes to improve and achieve success. We can learn about the coaches’ approach from the sport media and the sport science. The sport media gives athletes and coaches’ achievement and their life stories a place in the sport coverage. Moreover, in sport science many articles can be found focusing on athletes and coaches characteristics. -

The-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 the KA the Kick Algorithms ™

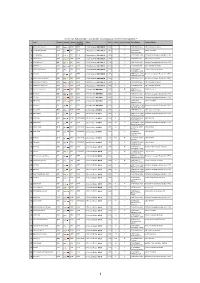

the-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 www.kickalgor.com the KA the Kick Algorithms ™ Club Country Country League Conf/Fed Class Coef +/- Place up/down Class Zone/Region Country Cluster Continent ⦿ 1 Manchester City FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,928 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 2 FC Bayern München GER GER � GER UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,907 -1 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 3 FC Barcelona ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,854 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 4 Liverpool FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,845 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 5 Real Madrid CF ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,786 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 6 Chelsea FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,752 +4 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⦿ 7 Paris Saint-Germain FRA FRA � FRA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,750 UEFA Western France / overseas territories Continental Europe ⦿ 8 Juventus ITA ITA � ITA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,749 -2 UEFA Central / East Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) Mediterranean Zone ⦿ 9 Club Atlético de Madrid ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,676 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 10 Manchester United FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,643 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 11 Tottenham Hotspur FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,628 -2 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⬇ 12 Borussia Dortmund GER GER � GER UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,541 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 13 Sevilla FC ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,531 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. -

Claremont Mckenna College an Exploration Into the Influence Of

Claremont McKenna College An Exploration into the Influence of Transfers on Share Prices for Publicly Traded Football Clubs SUBMITTED TO Professor Richard Burdekin AND DEAN NICHOLAS WARNER BY ANTHONY CONTRERAS For SENIOR THESIS Spring 2015 April 27, 2015 1 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................4 Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction .....................................................................................................................6 II. Literature Review ...........................................................................................................8 III. The Present Paper .......................................................................................................13 IV. Background to International Football .........................................................................15 IV.1 The Transfer Window .......................................................................................15 IV.2 The Transfer Process ....................................................................................... 16 IV.3 Ownership of Football Clubs ...........................................................................16 V. Preliminary Analysis ....................................................................................................17 V.1 Data Sources ......................................................................................................17 -

Rio Rapids Soccer Club Coaching Education Library

Rio Rapids Soccer Club Coaching Education Library Contact Ray Nause at [email protected] or 505-417-0610 to borrow from the library. Click on the item name for more detailed information. Format Item Author Date Loan Status 4-4-2 vs 4-3-3: An in-depth look at Jose Book Mourinho’s 4-3-3 and how it compares Michele Tossani 2009 Available to Alex Ferguson’s 4-4-2 A Nation of Wimps: The High Cost of Book Hara Estroff Marano 2008 Available Invasive Parenting Book Ajax Training Sessions Jorrit Smink 2004 Available Book Attacking Soccer – A Tactical Analysis Massimo Lucchesi 2001 Available Basic Training - Techniques and Tactics Success in Soccer, Book for Developing the Serious Player - 2002 Available Norbert Vieth Ages 6-14 - Volume 1 Beckham – Both Feet on the Ground: An David Beckham with Book 2003 Available Autobiography Tom Watt Best Practices for Coaching Soccer in the United States Soccer Book 2006 Available United States Federation Bobby Robson: High Noon - A Year at Book Jeff King 1997 Available Barcelona Bounce: Mozart, Federer, Picasso, Book Matthew Syed 2010 Available Beckham, and the Science of Success Challenger’s Competitive Team Training Book Challenger Sports 2004 Available Guide Challenger’s Parent Coach Coaching Book Challenger Sports Unknown Available Guide Book Challenger’s Top 100 Soccer Practices Challenger Sports 2004 Available Coaching for Teamwork – Winning Book Concepts for Business in the Twenty-First Vince Lombardi 1996 Available Century Book The Education of a Coach David Halberstam 2005 Available Book FUNino – -

Uefa Champions League 2012/13 Season Match Press Kit

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 2012/13 SEASON MATCH PRESS KIT Celtic FC SL Benfica Group G - Matchday 1 Celtic Park, Glasgow Wednesday 19 September 2012 20.45CET (19.45 local time) Contents Previous meetings.............................................................................................................2 Match background.............................................................................................................4 Match facts........................................................................................................................5 Squad list...........................................................................................................................7 Head coach.......................................................................................................................9 Match officials..................................................................................................................10 Fixtures and results.........................................................................................................11 Match-by-match lineups..................................................................................................13 Group Standings.............................................................................................................15 Competition facts.............................................................................................................17 Team facts.......................................................................................................................18 -

FOOMI-NET Working Paper No. 1

WILLIAMS, J. (2011), “Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011: Global Gendered Labor Markets”, foomi-net Working Papers No. 1, http://www.diasbola.com/uk/foomi-source.html FOOMI-NET www.diasbola.com Working Paper No. 1 Author: Jean Williams Title: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011: Global Gendered Labour Markets Date: 20.09.2011 Download: http://www.diasbola.com/uk/foomi-source.html Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011: Global Gendered Labour Markets Jean Williams Introduction A recently-published survey aimed at Britain's growing number of family historians, had, as its primary aim, to convey 'the range and diversity of women's work spanning the last two centuries - from bumboat women and nail-makers to doctors and civil servants - and to suggest ways of finding our more about what often seems to be a 'hidden history'.i Professional women football players are part of this hidden history. More surprisingly, no athletes were listed among the 300 or so entries, either in a generalist or specific category: perhaps, because of the significance of amateurism as a prevailing ethos in sport until the 1960s. Another newly-released academic survey by Deborah Simonton Women in 1 WILLIAMS, J. (2011), “Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011: Global Gendered Labor Markets”, foomi-net Working Papers No. 1, http://www.diasbola.com/uk/foomi-source.html European Culture and Society does makes reference to the rise of the female global sports star, beginning with Suzanne Lenglen's rather shocking appearance in short skirt, bandeau and sleeveless dress at Wimbledon in 1919 onwards.