Exhibit Hqi0211a P First Witness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inquiry Into Matters Relating to the Misuse of Electorate Office Staffing Entitlements

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA Legislative Council Privileges Committee Inquiry into matters relating to the misuse of electorate office staffing entitlements Parliament of Victoria Legislative Council Privileges Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2018 PP No 433, Session 2014‑18 ISBN 978 1 925703 64 1 (print version) 978 1 925703 65 8 (PDF version) Committee functions The Legislative Council Privileges Committee is established under Legislative Council Standing Orders Chapter 23 — Council Committees, and Sessional Orders. The Committee’s functions are to consider any matter regarding the privileges of the House referred to it by the Council. ii Legislative Council Privileges Committee Committee membership Mr James Purcell MLC Ms Nina Springle MLC Chair* Deputy Chair* Western Victoria South‑Eastern Metropolitan Hon. Philip Dalidakis MLC Mr Daniel Mulino MLC Mr Luke O’Sullivan MLC Southern Metropolitan Eastern Victoria Northern Victoria Hon. Gordon Rich-Phillips MLC Ms Jaclyn Symes MLC Hon. Mary Wooldridge MLC South‑Eastern Metropolitan Northern Victoria Eastern Metropolitan * Chair and Deputy Chair were appointed by resolution of the House on Wednesday, 23 May 2018 and Tuesday, 5 June 2018 respectively. Full extract of proceedings is reproduced in Appendix 2. Inquiry into matters relating to the misuse of electorate office staffing entitlements iii Committee secretariat Staff Anne Sargent, Deputy Clerk Keir Delaney, Assistant Clerk Committees Vivienne Bannan, Bills and Research Officer Matt Newington, Inquiry Officer Anique Owen, Research Assistant Kirra Vanzetti, Chamber and Committee Officer Christina Smith, Administrative Officer Committee contact details Address Legislative Council Privileges Committee Parliament of Victoria, Spring Street EAST MELBOURNE, VIC 3002 Phone 61 3 8682 2869 Email [email protected] Web http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/lc‑privileges This report is available on the Committee’s website. -

Over Policing; the Need for Execuitive Accountability During the Covid-19 Crisis

Inquiry into the Victorian Government's Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic Submission no. 20 OVER POLICING; THE NEED FOR EXECUITIVE ACCOUNTABILITY DURING THE COVID-19 CRISIS JACQUELINE WRIGHT I INTRODUCTION Following the Victorian Government’s health response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee have commenced a public inquiry to consider the effectiveness of the Victorian Government approach.1 This submission addresses the terms of reference of the inquiry by considering the lack of transparency surrounding Victoria’s over policing of vulnerable communities in response to the COVID-19 crisis. This submission considers this lack of transparency around the policing of assembly and movement, in light of executive responsibility as a principle of public law. This submission argues that the Victorian response to the COVID-19 crisis lacks transparency and effective reporting necessary for executive accountability. II EXECUTIVE AUTHORITY Whilst it is important for the Executive Government to be capable of and empowered to respond to a crisis be it war, natural disaster, financial crisis,2 or indeed a health emergency, a level of accountability is essential to prevent an executive power grab. In ascertaining the scope of power of the executive, the cautionary words of Dixon J come to mind: History and not only ancient history, shows that in countries where democratic institutions have been unconstitutionally superseded, it has been done not seldom by those holding the executive power. Forms of government may need -

To View Asset

Hepburn Health Service Report of Operations 2018‐19 To receive this publication in an accessible format phone 03 5321 6500 using the National Relay Service 13 36 77 if required, or email [email protected] Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne. © State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services, July 2019. Except where otherwise indicated, the images in this publication show models and illustrative settings only, and do not necessarily depict actual services, facilities or recipients of services. This publication may contain images of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Where the term ‘Aboriginal’ is used it refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indigenous is retained when it is part of the title of a report, program or quotation. Available at www.hhs.vic.gov.au Printed by Sovereign Press Ballarat Responsible bodies declaration In accordance with the Financial Management Act 1994, I am pleased to present the report of operations for Hepburn Health Service for the year ending 30 June 2019. Phillip Thomson Board Chair Daylesford 6 September 2019 1 Hepburn Health Service Report of Operations 2018‐19 Contents RESPONSIBLE BODIES DECLARATION ...................................................................................................... 1 ABOUT THIS REPORT ............................................................................................................................... 3 ESTABLISHMENT OF HEPBURN HEALTH ................................................................................................ -

30 May 2002 (Extract from Book 7)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 30 May 2002 (extract from Book 7) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Health............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Education Services and Minister for Youth Affairs......... The Hon. M. M. Gould, MLC Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Energy and Resources and Minister for Ports.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Minister for State and Regional Development, Treasurer and Minister for Innovation........................................ The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Workcover............ The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Senior Victorians and Minister for Consumer Affairs....... The Hon. C. M. Campbell, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Environment and Conservation.......................... The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections........................................ The Hon. A. Haermeyer, MP Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs............ The Hon. K. G. Hamilton, MP Attorney-General, Minister for Manufacturing Industry and Minister for Racing............................................ The Hon. R. J. Hulls, MP Minister for Education and Training................................ The Hon. L. J. Kosky, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Industrial Relations.............. The Hon. J. J. J. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 1 Tuesday, 21 December 2010 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier and Minister for the Arts................................... The Hon. E. N. Baillieu, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Police and Emergency Services, Minister for Bushfire Response, and Minister for Regional and Rural Development.................................................. The Hon. P. J. Ryan, MP Treasurer........................................................ The Hon. K. A. Wells, MP Minister for Innovation, Services and Small Business, and Minister for Tourism and Major Events...................................... The Hon. Louise Asher, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Finance........................... The Hon. R. W. Clark, MP Minister for Employment and Industrial Relations, and Minister for Manufacturing, Exports and Trade ............................... The Hon. R. A. G. Dalla-Riva, MLC Minister for Health and Minister for Ageing.......................... The Hon. D. M. Davis, MLC Minister for Sport and Recreation, and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs . The Hon. H. F. Delahunty, MP Minister for Education............................................ The Hon. M. F. Dixon, MP Minister for Planning............................................. The Hon. M. -

Help Save Quality Disability Services in Victoria HACSU MEMBER CAMPAIGNING KIT the Campaign Against Privatisation of Public Disability Services the Campaign So Far

Help save quality disability services in Victoria HACSU MEMBER CAMPAIGNING KIT The campaign against privatisation of public disability services The campaign so far... How can we win a This is where we are up to, but we still have a long way to go • Launched our marginal seats campaign against the • We have been participating in the NDIS Taskforce, Andrews Government. This includes 45,000 targeted active in the Taskforce subcommittees in relation to phone calls to three of Victoria’s most marginal seats the future workforce, working on issues of innovation quality NDIS? (Frankston, Carrum and Bentleigh). and training and building support against contracting out. HACSU is campaigning to save public disability services after the Andrews Labor • Staged a pre-Christmas statewide protest in Melbourne; an event that received widespread media • We are strongly advocating for detailed workforce Government’s announcement that it will privatise disability services. There’s been a wide attention. research that looks at the key issues of workforce range of campaign activities, and we’ve attracted the Government’s attention. retention and attraction, and the impact contracting • Set up a public petition; check it out via out would have on retention. However, to win this campaign, and maintain quality disability services for Victorians, dontdisposeofdisability.org, don’t forget to make sure your colleagues sign! • We have put forward an important disability service we have to sustain the grassroots union campaign. This means, every member has to quality policy, which is about the need for ongoing contribute. • HACSU is working hard to contact families, friends and recognition of disability work as a profession, like guardians of people with disabilities to further build nursing and teaching, and the introduction of new We need to be taking collective and individual actions. -

REPORT 2017- 2018 Victoria Police Pay Respect to the Traditional Owners of Lands on All Rights Reserved

ANNUAL REPORT 2017- 2018 Victoria Police pay respect to the traditional owners of lands on All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be which we live and work. We pay our respects to Elders and all reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who continue to form or by any means without the prior written permission of the care for their country, culture and people. State of Victoria (through Victoria Police). Authorised and published by Victoria Police. ISSN 2202-9672 (Print) Victoria Police Centre ISSN 2202-9680 (Online) 637 Flinders Street, Docklands VIC 3008 www.police.vic.gov.au Published September 2018 Print managed by Finsbury Green. This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication Designed by Bite Visual Communications Group. is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your This publication is available in PDF format on the internet at particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any www.police.vic.gov.au error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Consistent with the DataVic Access Policy issued by the Victorian Government in 2012, relevant information included in this Annual Report will be available at www.data.vic.gov.au in electronic readable format. © State of Victoria (Victoria Police) 2018 2 VICTORIA POLICE ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 CONTENTS FOREWORD FROM THE CHIEF COMMISSIONER 2 1. ABOUT VICTORIA POLICE 4 2. OUR PERFORMANCE 8 3. -

Book 7 28, 29 and 30 May 2002

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 7 28, 29 and 30 May 2002 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au\downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Health............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Education Services and Minister for Youth Affairs......... The Hon. M. M. Gould, MLC Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Energy and Resources and Minister for Ports.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Minister for State and Regional Development, Treasurer and Minister for Innovation........................................ The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Workcover............ The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Senior Victorians and Minister for Consumer Affairs....... The Hon. C. M. Campbell, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Environment and Conservation.......................... The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections........................................ The Hon. A. Haermeyer, MP Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Aboriginal Affairs............ The Hon. K. G. Hamilton, MP Attorney-General, Minister for Manufacturing Industry and Minister for Racing............................................ The Hon. R. J. Hulls, MP Minister for Education and Training................................ The Hon. L. J. Kosky, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Industrial Relations.............. The Hon. J. J. -

Annual Report

Department of Justice and Regulation Annual Report 2016–17 Publication information The Department of Justice and Regulation acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land of Victoria and pays respect to their Elders, both past and present. Throughout this document the term ‘Koori’ is used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Use of the terms ‘Aboriginal’ and ‘Indigenous’ are retained in the names of some programs, titles and initiatives, and, unless noted otherwise, are inclusive of both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne. Printed by Waratah Group, Port Melbourne October 2017 © Government of Victoria This report is protected by copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, and those explicitly granted below, all other rights are reserved. Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format please telephone (03) 8684 0300. Also published in an accessible format on www.justice.vic.gov.au. Unless indicated otherwise, this work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au. It is a condition of this Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Licence that you must give credit to the original author, which is the State of Victoria. Designed by Think Productions This report is printed on Ecostar which is manufactured from 100% Post Consumer Recycled under the ISO 14001 environmental management system. Ecostar is an environmentally responsible paper made Carbon Neutral. -

AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION UNION Victorian Labor

AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION UNION Victorian Branch Victorian Labor MPs We want you to email the MP in the electoral district where your school is based. If your school is not in a Labor held area then please email a Victorian Labor upper house MP who covers your area from the separate list below. Click here if you need to look it up. Email your local MP and cc the Education Minister and the Premier Legislative Assembly MPs (lower house) ELECTORAL DISTRICT MP NAME MP EMAIL MP TELEPHONE Albert Park Martin Foley [email protected] (03) 9646 7173 Altona Jill Hennessy [email protected] (03) 9395 0221 Bass Jordan Crugname [email protected] (03) 5672 4755 Bayswater Jackson Taylor [email protected] (03) 9738 0577 Bellarine Lisa Neville [email protected] (03) 5250 1987 Bendigo East Jacinta Allan [email protected] (03) 5443 2144 Bendigo West Maree Edwards [email protected] 03 5410 2444 Bentleigh Nick Staikos [email protected] (03) 9579 7222 Box Hill Paul Hamer [email protected] (03) 9898 6606 Broadmeadows Frank McGuire [email protected] (03) 9300 3851 Bundoora Colin Brooks [email protected] (03) 9467 5657 Buninyong Michaela Settle [email protected] (03) 5331 7722 Activate. Educate. Unite. 1 Burwood Will Fowles [email protected] (03) 9809 1857 Carrum Sonya Kilkenny [email protected] (03) 9773 2727 Clarinda Meng -

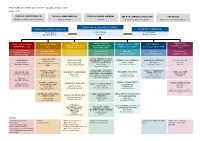

DPC-Org-Chart-April-2021.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF PREMIER AND CABINET— ORGANISATIONAL CHART 12 April 2021 THE HON. DANNY PEARSON THE HON. JAMES MERLINO THE HON. DANIEL ANDREWS THE HON. GABRIELLE WILLIAMS TIM PALLAS Minister for Government Services Deputy Premier Premier Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Minister for Industrial Relations DEPARTMENT OF PREMIER AND CABINET RECOVERY TRACKING & ANALYTICS OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Marcus Walsh Jeremi Moule Jane Gardam Executive Director Secretary Executive Director CABINET, SOCIAL POLICY & INDUSTRIAL LEGAL, LEGISLATION & DIGITAL VICTORIA ECONOMIC POLICY & STATE FIRST PEOPLES— COMMUNICATIONS & INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS VICTORIA GOVERNANCE (LLG) (DV) PRODUCTIVITY (EPSP) STATE RELATIONS (FPSR) CORPORATE (CCC) RELATIONS (SPIR) (IRV) Toby Hemming Vivien Allimonos Vivien Allimonos Kate Houghton Tim Ada Elly Patira Matt O’Connor Deputy Secretary & A/ Chief Executive Officer Deputy Secretary Deputy Secretary Deputy Secretary A/ Deputy Secretary Deputy Secretary General Counsel CYBERSECURITY COVID COORDINATION & GOVERNANCE CABINET OFFICE PERFORMANCE / FAMILIES, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ABORIGINAL VICTORIA PRIVATE SECTOR John O’Driscoll Vicky Hudson FAIRNESS & HOUSING Sophie Colquitt Tim Kanoa Lissa Zass Chief Information Security Rachel Cowling Executive Director Lucy Toovey A/ Executive Director Executive Director Director Officer A/ Executive Director Executive Director DIGITAL DESIGN & EDUCATION / JUSTICE / TREATY / ABORIGINAL OFFICE OF THE COMMUNITY SECURITY & ECONOMIC STRATEGY PUBLIC SECTOR INNOVATION CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AFFAIRS POLICY -

The Minority Report

THE MINORITY REPORT Inquiry into the Victorian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. INTRODUCTION On 23 April 2020, in the Victorian Parliament during Question Time, the Premier of Victoria, the Hon Daniel Andrews MP, stated confidently: “[The Public Accounts and Estimates Committee] is the pre-eminent committee in our Parliament, and it ought to be given the opportunity to review the performance of the government. I am confident that it will do that without fear or favour.”1 The Andrews Labor Government’s handling of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, in particular the deadly second wave outbreak of infections, has been nothing short of disastrous. It has had dramatic impacts on all Victorians, with the loss of more than 800 lives, hundreds of thousands of jobs, many thousands of businesses and the deprivation of the liberty of millions of Victorians. The Public Accounts and Estimates Committee (PAEC) was given the task of reviewing the Government’s handling of the biggest health, social and economic crisis in generations. In the view of the minority members of the Committee, this was the wrong choice. A committee dominated by Labor Government members and chaired by a Labor Government member, with both a deliberative and a casting vote on all matters, would never deliver the necessary critical examination or accountability necessary in this crisis. Evidence gathered in preparation for this Inquiry showed that Victoria was the only jurisdiction in Australia with a Parliamentary committee reviewing a government response to the pandemic, with a government majority. When fundamental mistakes made by government caused a second wave of COVID-19 that cost 800 Victorian lives, deepened and extended Victoria’s social and economic misery and led to enormous imposts of the liberty of Victorians, a committee dominated by a Labor Government majority was entirely inappropriate.