HKIA Journal Issue No. 72

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5482 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5483 Yau Tsim Mong Block 2, The Long Beach 5484 Kwun Tong Dorsett Kwun Tong, Hong Kong 5486 Wan Chai Victoria Heights, 43A Stubbs Road 5487 Islands Tower 3, The Visionary 5488 Sha Tin Yue Chak House, Yue Tin Court 5492 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5496 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5497 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5498 Kowloon City Sik Man House, Ho Man Tin Estate 5499 Wan Chai 168 Tung Lo Wan Road 5500 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5501 Sai Kung Clear Water Bay Apartments 5502 Southern Red Hill Park 5503 Sai Kung Po Lam Estate, Po Tai House 5504 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5505 Islands Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5506 Kwun Tong Block 17, Laguna City 5507 Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Kowloon East Sai Kung 5509 Hotel Eastern Tower 2, Pacific Palisades 5510 Kowloon City Billion Court 5511 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5512 Central & Western Tai Fat Building 5513 Wan Chai Malibu Garden 5514 Sai Kung Alto Residences 5515 Wan Chai Chee On Building 5516 Sai Kung Block 2, Hillview Court 5517 Tsuen Wan Hoi Pa San Tsuen 5518 Central & Western Flourish Court 5520 1 Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wong Tai Sin Fu Tung House, Tung Tau Estate 5521 Yau Tsim Mong Tai Chuen Building, Cosmopolitan Estates 5523 Yau Tsim Mong Yan Hong Building 5524 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5525 Sha Tin Yiu Ping House, Yiu On Estate 5526 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5529 Wan Chai Block E, Beverly Hill 5530 Yau Tsim Mong Tower 1, The Harbourside 5531 Yuen Long Wah Choi House, Tin Wah Estate 5532 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5533 Yau Tsim Mong Paradise Square 5534 Kowloon City Tower 3, K. -

A Liveable Compact City? Local Perspectives from Hong Kong

Utrecht University A Liveable Compact City? Local Perspectives from Hong Kong Master of Science in Spatial Planning Faculty of Geosciences Utrecht University Ka Sik Tong February 2018 A Liveable Compact City? Local Perspectives from Hong Kong Master of Science in Spatial Planning November 2017 Ka Sik Tong Student ID: 5922402 [email protected] Supervised by Professor Dr. Jochen Monstadt Utrecht University Faculty of Geosciences PREFACE This dissertation is original, unpublished, independent work by Ka Sik Tong. This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Master of Science at Utrecht University. This research described herein was conducted under the supervision of Professor Jochen Monstadt in the Department of Geoscience, Utrecht University, between August 2017 and March 2018. Ka Sik Tong March 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2017 August marked the start of this 7-months long journey, and I am finally writing this note of thanks. It has been an intense period for me, in all aspects. It is much tougher, but it also means much greater than I thought it would be. I would like to at this moment, express my sincere thanks to all precious people who have supported and helped me so much throughout this period. I am incredibly grateful to my supervisor Professor Dr Jochen Monstadt for his guidance and support throughout these months. I would like to also, express my thanks to all interviewees who try their best in helping me, providing all the great information for this study. I would like to thank my parents, who have been supporting me throughout the two years long journey. -

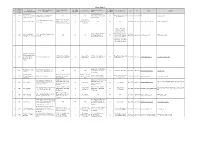

Rsps of the Second Phase of the Pilot Scheme in Kwun Tong District

Sham Shui Po District Name of Name of Recognised Service Address of Day Care No. of Day Address of Home Care No. of Home S/N (location of Serving District(s) Serving District(s) Tel Fax Email Website Agency/Organisation Provider Centre Care Places Office Care Places centre) Association for Unit 207-212, Block 44, Association for Engineering and Wong Tai Sin, Sham Shui 1 SSP Engineering and Medical NA NA NA Podium Floor, Shek Kip Mei 10 2779 8333 2779 8821 NA www.emv.org.hk Medical Volunteer Services Po, Kowloon City Volunteer Services Estate, Kowloon Unit 110-113, G/F., Lai Lo Sham Shui Po, Caritas Mutual Help Project (Day 2 SSP Caritas - Hong Kong House, Lai Kok Estate, 24 Kowloon City, Yau NA NA NA 2387 0966 2387 0070 [email protected] www.caritasse.org.hk Care Centre) Cheung Sha Wan, Kowloon Tsim Mong Eastern, Wan Chai, Central & Western, Southern, Kwun Tong, Unit B & D, 8/F, D2 Place 2, Wong Tai Sin, Sai Kung, Care U Professional Care U Professional Nursing Service 2628 7020 / 3 SSP NA NA NA 15 Cheung Shun Street, 50 Sham Shui Po, Kowloon 2628 3002 [email protected] www.careu.com.hk Nursing Service Limited Limited# 6737 1999 Cheung Sha Wan, KLN City, Yau Tsim Mong, Sha Tin, Tai Po, North, Kwai Tsing, Tsuen Wan, Tuen Mun, Yuen Long Hong Kong Baptist Mr. & Mrs. Au Shue Hung 1/F, No. 55 Cornwall Street, Sham Shui Po, 1/F, No. 55 Cornwall Street, Wong Tai Sin, Sham Shui 4 SSP Rehabilitation And The Wonderland Day Centre 20 40 2776 8338 2311 9122 [email protected] http://www.ashrh.org.hk/ Kowloon Tong, Kowloon Kowloon City Kowloon Tong, Kowloon Po, Kowloon City Healthcare Home Limited Room 1, G/F, On Tin House, Hong Kong Christian Shamshuipo Integrated Home Care 5 SSP NA NA NA Pak Tin Estate, Sham Shui 30 Shamshuipo, Kwai Tsing 6756 5789 2778 1129 [email protected] www.hkcs.org Service Service Team - Wonderful Care# Po, Kowloon Hong Kong Young Room 215-216, 2/F, No. -

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

List of buildings with confirmed / probable cases of COVID-19 List of residential buildings in which confirmed / probable cases have resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date) District Building name Related confirmed / probable case number Sai Kung Yee Ching House Yee Ming Estate 58,128 Wan Chai Envoy Garden 114, 213 Case notified by the health Southern Block 28, Baguio Villa authority of Canada and Case 117, 118 Tai Po Heng Tai House, Fu Heng Estate 119, 124, 140 Tuen Mun On Hei House, Siu Hei Court 120, 121 Sha Tin Mau Lam House, Kwong Lam Court 122 Tsuen Wan Tower 7, Bellagio 123, 129 Kwun Tong Block T, Telford Gardens 125 Kwun Tong Block 26, Phase 2, Laguna City 126, 127 130, 131,133, Kwai Tsing iPlace 138 Central & Western Serene Court, 35 Sai Ning Street 132 Tai Po Ng Tung Chai, Lam Tsuen 134 Central & Western View Villa 135 Southern 18 Stanley Main Street 136 Wan Chai Block A, Tai Hang Terrace 137 Eastern Cornell Centre 139 Sai Kung 684 Clear Water Bay Road 141 Kwai Tsing Tivoli Garden 142 North Lai Ming House, Wah Ming Estate 143 Sai Kung The Palisades 145 Eastern Fort Mansion 146 Central & Western Kellett View Town Houses, 65 Mount 147, 148 District Building name Related confirmed / probable case number Kellett Road Southern Wah Cheong House, Wah Fu 2 Estate 149 Yau Tsim Mong Hotel ICON 150 Yau Tsim Mong Block A, Chungking Mansions 151 Tuen Mun Tower 1, Oceania Heights 152 Shatin Block 10, Pristine Villa 153 Kowloon City 8 Hok Ling Street 154 Wong Tai Sin Lung Chu House, Lung Poon -

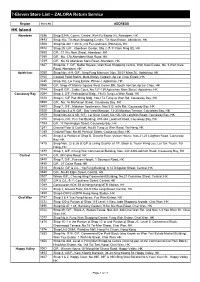

7-Eleven Store List – ZALORA Return Service HK Island

7-Eleven Store List – ZALORA Return Service Region Store No. ADDRESS HK Island Aberdeen 0286 Shop S24A, Comm. Centre, Wah Fu Estate (II), Aberdeen, HK 0493 Shop 102, Tin Wan Shopping Centre, Tin Wan Estate, Aberdeen, HK 0568 Shop No.401 + 401A, Chi Fu Landmark, Pokfulam, HK 0572 Shop 25, G/F., Aberdeen Center, Site 2 (7-11 Nam Ning St), HK 0688 G/F., 11 Wu Nam Street, Aberdeen, HK 1089 G/F., No. 178 Aberdeen Main Road, HK 1239 G/F., No.38 Aberdeen Main Road, Aberdeen, HK 1607 Shop No. 1, G/F, Noble Square, Wah Kwai Shopping Centre, Wah Kwai Estate, No. 3 Wah Kwai Road, Aberdeen, HK Apleichau 0030 Shop Nos. 6-9, G/F., Ning Fung Mansion, Nos. 25-31 Main St., Apleichau, HK 0165 Cooked Food Stall 6, Multi-Storey Carpark, Ap Lei Chau Estate, HK 0235 Shop 102, Lei Tung Estate, Phase I, Apleichau, HK 0366 G/F, Shop 47 Marina Square West Comm Blk, South Horizon,Ap Lei Chau, HK 0744 Shop B G/F., Coble Court, No.127-139 Apleichau Main Street, Apleichau, HK Causeway Bay 0094 Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0325 Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK 0468 G/F., No. 16 Matheson Street, Causeway Bay, HK 0608 Shop 7, G/F., Malahon Apartments, Nos.513 Jaffe Rd., Causeway Bay, HK 0920 Shop Nos.8 & 9, G/F., Bay View Mansion, 13-33 Moreton Terrace, Causeway Bay, HK 0929 Shop Nos.6A & 6B, G/F., Lei Shun Court, No.106-126 Leighton Road, Causeway Bay, HK 1075 Shop G, G/F, Pun Tak Building, 478-484 Lockhart Road, Causeway Bay, HK 1153 G/F, 17 Pennington Street, Causeway Bay, HK 1241 Ground Floor & Cockloft, No.68 Tung Lo Wan Road, Tai Hang, HK 1289 Ground Floor, No.60 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, HK 1295 Shop A & Portion of Shop B, Ground Floor, Vulcan House, Nos.21-23 Leighton Road, Causeway Bay, HK 1475 Shop Nos. -

A Study on the Fire Safety Management of Public Rental Housing in Hong Kong 香港公共房屋消防安全管理制度之探討

Copyright Warning Use of this thesis/dissertation/project is for the purpose of private study or scholarly research only. Users must comply with the Copyright Ordinance. Anyone who consults this thesis/dissertation/project is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no part of it may be reproduced without the author’s prior written consent. CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG 香港城市大學 A Study on the Fire Safety Management of Public Rental Housing in Hong Kong 香港公共房屋消防安全管理制度之探討 Submitted to Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering 土木及建築工程系 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Engineering Doctorate 工程學博士學位 by Yeung Cho Hung 楊楚鴻 September 2012 二零一二年九月 i Abstract of dissertation entitled: A Study on the Fire Safety Management of Public Rental Housing in Hong Kong submitted by YEUNG CHO HUNG for the degree of Engineering Doctorate in Civil and Architectural Engineering at The City University of Hong Kong in September, 2012. ABSTRACT At the end of the Pacific War, there were a large number of refugees flowing into Hong Kong from the Mainland China. Many of them lived in illegal squatter areas. In 1953, a big fire occurred in Shek Kip Mei squatter area which rendered these people homeless. The disastrous fire embarked upon the long term public housing development in Hong Kong. Today, the Hong Kong Housing Authority (HKHA) which was established pursuant to the Housing Ordinance is charged with the responsibility to develop and implement a public housing programme in meeting the housing needs of people who cannot afford private rental housing. It is always a big challenge for the HKHA to manage and maintain a large portfolio of residential properties which were built across several decades under different architectural standards and topology. -

1 Introduction, Elvis Presley and the Beatles

Learning and Teaching of Local and Western Popular Music (Re-run) Introduction, Elvis Presley and the Beatles 3 May 2016 What is popular music? Having wide appeal to large audiences Commodity – a product of music industry Produced and stored in non-written form Difference between popular music and pop music? Pop music refers to a specific musical genre. What are the important features in popular music? Social and cultural contexts, lyrics, musical characteristics Four focuses: harmony, rhythm utilisation, instrumentation, structure (melody, tempo, tone colour, duration) Structure: Why we love REPETITION in music? “The Mere Exposure Effect” Duration – 2 to 3 mins Melody – step, repeated notes, leaps, Riff (fill) (repeated chord progression) , Lick (single-note melodic lines) Groove is the sense of propulsive rhythmic “feel” or sense of “swing Hook (主題句?) is a musical idea, a passage or phrase repeats several times Don’t Take the Girl – Tim McGraw 1994 – His first No.1 single on the Hot Country Songs chart Rhythm – syncopations Harmony – I, IV, V (ii, iii, vi) Treatment of Melody, Rhythm & Harmony in relation to Tempo Lyrics – question & answer, contrast, descriptive, repetition with variations Contexts – social, economic and cultural background: Blowing’ in the Wind – Bod Dylan, May 1963 Drum set / Drum kit Bass drum with the right-foot pedal, provides the basic beat Snare drum provides the strongest regular accents Hi-hat stand and cymbals provide finer rhythms, mark the change from one passage to another One or more tom-tom drums provide drum fills and solos One or more cymbals provide strong accent marker and musical effect What were the social and cultural contexts in the 1950s? 4 M immigrants to the States after WWII (after 1946) USA was one of the countries that benefited from the WWII Baby boom 1946-1964 about 78 M people 1950s America was a wealthy and powerful nation, but a troubled one; racial prejudice Respectable, middle-class White teenagers didn’t listen to race music. -

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total No

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total no. of electors: 869) Trade Union Union Name (English) Postal Address (English) Registration No. 7 Hong Kong & Kowloon Carpenters General Union 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. 8 Hong Kong & Kowloon European-Style Tailors Union 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 15 Hong Kong and Kowloon Western-styled Lady Dress Makers Guild 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 17 HK Electric Investments Limited Employees Union 6/F., Kingsfield Centre, 18 Shell Street,North Point, Hong Kong. Hong Kong & Kowloon Spinning, Weaving & Dyeing Trade 18 1/F., Kam Fung Court, 18 Tai UK Street,Tsuen Wan, N.T. Workers General Union 21 Hong Kong Rubber and Plastic Industry Employees Union 1st Floor, 20-24 Choi Hung Road,San Po Kong, Kowloon DAIRY PRODUCTS, BEVERAGE AND FOOD INDUSTRIES 22 368-374 Lockhart Road, 1/F.,Wan Chai, Hong Kong. EMPLOYEES UNION Hong Kong and Kowloon Bamboo Scaffolding Workers Union 28 2/F, Wah Hing Com. Centre,383 Shanghai St., Yaumatei, Kln. (Tung-King) Hong Kong & Kowloon Dockyards and Wharves Carpenters 29 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. General Union 31 Hong Kong & Kowloon Painters, Sofa & Furniture Workers Union 1/F, 368 Lockhart Road,Pakling Building,Wanchai, Hong Kong. 32 Hong Kong Postal Workers Union 2/F., Cheng Hong Building,47-57 Temple Street, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon. 33 Hong Kong and Kowloon Tobacco Trade Workers General Union 1/F, Pak Ling Building,368-374 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong HONG KONG MEDICAL & HEALTH CHINESE STAFF 40 12/F, United Chinese Bank Building,18 Tai Po Road,Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. -

List of Clinics Coordinated by the Home Affairs Department to Provide Injectable Inactivated Influenza Vaccines Under the Special Arrangement

List of clinics coordinated by the Home Affairs Department to provide injectable inactivated influenza vaccines under the Special Arrangement Hong Kong District Name of Clinic Address Enquiry phone number No clinic providing service in this district List of clinics coordinated by the Home Affairs Department to provide injectable inactivated influenza vaccines under the Special Arrangement Kowloon District Name of Clinic Address Enquiry phone number Shop 11, 1-7 Wu Kwong Street, Leung Shu Piu 2954 2661 HUNG HOM, KOWLOON Kowloon City Lok Sin Tong Chan Kwong Hing G/F, 48 Junction Road, 2383 1470 Memorial Primary Health Centre KOWLOON CITY, KOWLOON Room A, G/F, 3 Tsui Ping Road, Christian Family Service Centre 2950 8105 KWUN TONG, KOWLOON Kwun Tong Shop 204, G/F, Tak King House, Tak Hong Family Medical Centre 2709 6677 Tak Tin Estate, LAM TIN, KOWLOON Sham Shui Po District Council Po Shop 101, Mei Kwai House, Shek Kip Mei Estate, Sham Shui Po Leung Kuk Shek Kip Mei Community 2390 2711 13 Pak Tin Street, SHAM SHUI PO, KOWLOON Services Centre (Medical Services) G/F, Unit C, Sik Sik Yuen Social Services Complex, Wong Tai Sin Sik Sik Yuen Clinic 2328 4929 38 Fung Tak Road, WONG TAI SIN, KOWLOON The Lok Sin Tong Flat A&B, 3/F, 688 Shanghai Street, Yau Tsim Mong 2391 1073 Chan Cho Chak Polyclinic Mongkok MONGKOK, KOWLOON List of clinics coordinated by the Home Affairs Department to provide injectable inactivated influenza vaccines under the Special Arrangement New Territories District Name of Clinic Address Enquiry phone number Shop No.9, 1/F, -

Address of Estate Offices Under Hong Kong Housing Authority and Hong Kong Housing Authority Customer Service Centre

香港房屋委員會轄下屋邨辦事處及香港房屋委員會客務中心地址 Address of Estate Offices under Hong Kong Housing Authority and Hong Kong Housing Authority Customer Service Centre 辦事處名稱 Name of Office 地址 Address 香港房屋委員會客務 Hong Kong Housing 九龍橫頭磡南道3號 3 Wang Tau Hom South Road, 中心 Authority Customer Kowloon Service Centre 鴨脷洲邨辦事處 Ap Lei Chau Estate 香港鴨脷洲邨利滿樓(高座)地下24- No. 24-31, G/F, Lei Moon House Office 31號 (High Block), Ap Lei Chau Estate, Hong Kong 蝴蝶邨辦事處 Butterfly Estate Office 屯門蝴蝶邨蝶聚樓地下 G/F, Tip Chui House, Butterfly Estate, Tuen Mun 柴灣邨物業服務辦事 Chai Wan Estate Property 柴灣柴灣邨灣畔樓地下 G/F, Wan Poon House, Chai Wan 處 Services Management Estate, Chai Wan Office 澤安邨辦事處 Chak On Estate Office 深水埗澤安邨華澤樓地下17A-24號 Unit 17A-24, G/F, Wah Chak House, Chak On Estate, Sham Shui Po 長青邨物業服務辦事 Cheung Ching Estate 青衣長青邨青槐樓地下20-29號 Unit 20-29, G/F, Ching Wai House, 處 Property Services Cheung Ching Estate, Tsing Yi Management Office 長亨邨物業服務辦事 Cheung Hang Estate 青衣長亨邨亨麗樓地下1-8號 Unit 1-8, G/F, Hang Lai House, 處 Property Services Chueng Hang Estate, Tsing Yi Management Office 長康邨辦事處 Cheung Hong Estate 青衣長康邨康平樓地下 G/F, Hong Ping House, Cheung Hong Office Estate, Tsing Yi 長貴邨物業服務辦事 Cheung Kwai Estate 長洲長貴邨長旺樓101-102號 Unit 101-102, Cheung Wong House, 處 Property Services Cheung Kwai Estate, Cheung Chau Management Office 祥龍圍邨物業服務辦 Cheung Lung Wai Estate 上水祥龍圍邨景祥樓地下 G/F, King Cheung House, Cheung 事處 Property Services Lung Wai Estate, Sheung Shui Management Office 長沙灣邨物業服務辦 Cheung Sha Wan Estate 深水埗長沙灣邨長泰樓一樓 1/F, Cheung Tai House, Cheung Sha 事處 Property Services Wan Estate, Sham Shui Po Management Office -

Tuen Ma Line East Rail Line

Lo Wu Estimated Travelling Time Lok Ma Chau Kai Tak Station Concourse Layout Plan of Kai Tak Station Trade and 沐虹街 upon Full Commissioning # Industry Tower To Concorde Road Concorde Road Kai Ching Estate Around 10 minutes East Rail Line East Rail Line passengers travelling southward from Prince Edward Road East Kai Tak Community Hall Concorde Road the New Territories to Muk Yuen Street Kai Tak Tai Wai Kowloon can interchange to the Tuen Ma Line at Tai Around 3 minutes Wu Kai Sha Wai Station. This will help alleviate the congestion Kai Tak Diamond Hill between Tai Wai and Muk Chui Street Kowloon Tong stations. # Actual travelling time may vary Kai Ching Estate depending on the situation. The new railway facilitates community development by De Novo Tuen Mun Tai Wai extending service to areas which are not covered by Legend Kai Long Court To Station Square existing railways. Escalators Lifts Kiosks Hin Keng Station entrance Kai Tak Station Tak Long Estate Tuen Ma Line Lift Kai Tak River Stairs Ticket gates Paid area To Kai Ching Estate Diamond Hill Escalator Toilets/Babycare room Ticket issuing machines Kai Tak Stairs Muk On Street Sung Wong Toi Temporary pedestrian Station Square To Kwa Wan Tai Wai to connectivity One Kai Tak Ho Man Tin Hung Hom Section Tuen Ma Line Art-in-Station Hung Hom to Hung Hom Admiralty Section 8 stations 4 interchange stations 2 interchange stations Admiralty Exhibition Centre Station Features Kai Tak Station is an underground station with 3 entrances, All 3 above-ground entrances are installed with glass panels -

九七年三月二十一日 文書stdb 259/94-97

For information STDC Paper 90/2013 on 21 November 2013 Sha Tin District Council Report on the meeting of the Traffic and Transport Committee held on 5 November 2013 (1) The Committee discussed the following: (i) paper on “ ‘Traffic and Transport Consultancy Study on Cycling Networks and Parking Facilities in Existing New Towns in Hong Kong’ and ‘Tai Po Pilot Scheme’ ” submitted by the Transport Department; (ii) paper on “ ‘Universal Accessibility’ Programme – Construction of Barrier-free Access Facilities at the Footbridge over Tai Po Road (Sha Tin Section) and East Rail Line near Wo Che Street (Structure No.: NF40)” submitted by the Highways Department, and passed this paper unanimously; (iii) replies of the Transport Department, Environmental Protection Department and MTR Corporation Limited to the question on “Noise Caused by East Rail Trains”; (iv) reply of the Transport Department to the question on “Tate’s Cairn Tunnel Bus Interchange”, and passed the following provisional motion unanimously: “The Traffic and Transport Committee of the Sha Tin District Council strongly requests the Administration to urge the Tate's Cairn Tunnel Company Limited to retrofit lifts at the footbridge of Tate's Cairn Tunnel as soon as possible for use by the mobility-handicapped and the elderly.”; (v) replies of the Transport Department, Social Welfare Department, Hong Kong Police Force and Hospital Authority to the question on “Safety of Electric Wheelchairs”; (vi) replies of the Transport Department, Kowloon Motor Bus Company (1933) Limited (KMB), New