Public Domain: Available but Not Always Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It's a Wonderful Life

It’s a Wonderful Life KIOWA COUNTY 4 Watch the Table of Contents Movie Online 2 Reflections on a Small Town 4 Becoming George Bailey Three Journeys to One 10 Destination Three Poems by Two 14 Campbells 16 The Signature of a Life 22 Rural Free Delivery Holiday Tournament Defines 24 Christmas in Southeast CO 28 Eva’s Christmas Story “You see, George, you really 30 do have a wonderful life” Kiowa County Independent Publisher Betsy Barnett Advertising Cindy McLoud 1316 Maine Street Editor Priscilla Waggoner Web Page Kayla Murdock PO Box 272 Layout and Design William Brandt Distribution Denise Nelson Eads, CO 81036 Advertising John Contreras Special thanks to Sherri Mabe for use of [email protected] her photos: sherrimabeimages.com. Kiowa Countykiowacountyindependent.com Independent © December 2018 It’s a Wonderful Life | 1 ne morning not long ago, a prominent, local are, nonetheless, the things he does. What he is… man came into the newspaper office. He’s is a thinker. And he’d clearly been thinking about Odone that a few times before. He might be something that morning because he clearly had on his way to Denver, or he might have come to something to say. town on business. Whatever the circumstance or, “I’ve been all around the world,” he began. he’s stopped by the office just to say hello, just to “Russia. Asia. All sorts of different places in Eu- make sure we’re continuing to do what we do and, rope—I’ve been there. I’ve been very lucky to sometimes, just to let us know he’s glad we’re do- have opportunities present themselves that just ing it. -

Isolation in Cornell Woolrich's Short Fiction

WINDOW DRESSING: ISOLATION IN CORNELL WOOLRICH’S SHORT FICTION by Annika R.P. Deutsch A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English, Literature Boise State University May 2017 © 2017 Annika R.P. Deutsch ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Annika R.P. Deutsch Thesis Title: Window Dressing: Isolation in Cornell Woolrich’s Short Fiction Date of Final Oral Examination: 27 February 2017 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Annika R.P. Deutsch, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Jacqueline O’Connor, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Ralph Clare, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Jeff Westover, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Jacqueline O’Connor, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved by the Graduate College. DEDICATION For my mom Marie and my dad Bill, who have always supported and encouraged me. For my sisters Elizabeth and Emily (and nephew Kingsley—I can’t forget you!), who always have confidence in me even when I don’t. For my dog Sawyer, who has provided me with 10 years of unconditional love. For my husband Ben, who is a recent addition but stands by me like the family he now is. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to my chair, Jacky O’Connor, for being excited by this project and working alongside me to make it what it is today. -

The Man Who Invented Christmas Film Adaptations of Dickens’ a Christmas Carol Dr Christine Corton

10TH DECEMBER 2019 The Man Who Invented Christmas Film Adaptations of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol Dr Christine Corton A Christmas Carol is now over 175 years old. Written in 1843, it is certainly the most televised of Dickens’s works and equals if not beats, its closest rival, Oliver Twist (1837-39) for cinema releases. It’s had a huge influence on the way we understand the Christmas festival. It was written at a time when the festival was being revived after centuries of neglect. And its impact was almost immediate. A Christmas Carol quickly achieved iconic status, far more so than any of Dickens’s other Christmas stories. You have to have been living on some far-off planet not to have heard of the story – the word ‘Scrooge’ has come to represent miserliness and ‘Bah, Humbug’ is a phrase often resorted to when indicating someone is a curmudgeon. Even, Field Marshall Montgomery concluded his Christmas Eve message to the Eighth Army on the battlefield with Tiny Tim’s blessing. In 1836 Dickens described Christmas at Dingley Dell in The Pickwick Papers in which of course one of the most famous of the interpolated tales appears, The Story of the Goblins who Stole a Sexton and for those who know the tale, the miserable and mean Gabriel Grub is not a million miles away from Scrooge. Both Mr Pickwick’s Christmas at Wardle’s (1901) and Gabriel Grub: The Surly Sexton (1904) were used as the basis for silent films at around the same time as the first silent version of the 11 minute long: Scrooge: Or Marley’s Ghost which was released in 1901. -

Of Egyptian Gulf Blockade Starting at 11 A.M

y' y / l i , : r . \ ' < r . ■ « • - t . - FRroAY, MAY 26, 1987 FACE TWENTY-FOUR iianrtfifat^r lEn^nUts ll^ralb Average Daily Net Pi’ess Run The W eadier,;v 5 ; For The Week Ended Sunny, milder Pvt Ronald F. Oirouard, bon Presidents nnd Vice Presi May 20, 1067 65-70, clear and opol of Mrs. Josephine Walsh of Instruction Set dents, Mrs. Doris Hogan;, Secre- low about 40; moeOy fWr About Town 317 Tolland Tpke., and. Pvt Ray-Totten U TKTA IWbert Schuster; Joy n il. 1-iO U nC ll Treosurera, Geoige Dickie; Leg^ ' DAVIS BAKERY « mild ionfiorrow, taigta hi 70A The VFW Aiixlliexy has been Barry N. Smith, son of Mr. 15 ,2 1 0 and Mrs.' NeWton R. &nlth of islailve and Council Delegaites, ManOhenter—^A CUy, of Village Charm Invited to attend and bring the Tlie Mancheater PTA OouncU Lloyd Berry; Program, Mia. 32 S. Main St., have rec^ itly PRICE SEVEN CHM29 co lo n to the J<^nt installation ■wm sponsor a school of instruc- ca^riene- Taylor; Membership, (ClaMlfied Adverttsttit on Page IS) completed an Army advanced WILL BE CLOSED MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, MAY 27, 1967 « f oiTteers of the Glastonbury tion for incoming officers and Eleanor McBatai; PubUclty, VOL. LXXXVI, NO. 202 (SIXTEEN PAGES—TV SECTION) infantry course at F t Jackson, VPW Poet and AuxllttmT Sat ooenmittee members of Districts i^tonchester Hoiald staff; Ways S.C. M O N , MAY 29 S TUES,.IIAY 80 urday at 8 pjn. at the poet One an<| Two at Bowers School Means, Mot. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e. -

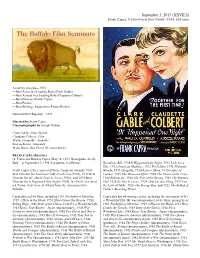

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 Min)

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 min) Academy Awards—1935: —Best Actor in a Leading Role (Clark Gable) —Best Actress in a Leading Role (Claudette Colbert) —Best Director (Frank Capra) —Best Picture —Best Writing, Adaptation (Robert Riskin) National Film Registry—1993 Directed by Frank Capra Cinematography by Joseph Walker Clark Gable...Peter Warne Claudette Colbert...Ellie Walter Connolly...Andrews Roscoe Karns...Shapeley Ward Bond...Bus Driver #1 (uncredited) FRANK CAPRA (director) (b. Francesco Rosario Capra, May 18, 1897, Bisacquino, Sicily, Italy—d. September 3, 1991, La Quinta, California) Broadway Bill, 1934 It Happened One Night, 1933 Lady for a Day, 1932 American Madness, 1932 Forbidden, 1931 Platinum Frank Capra is the recipient of three Academy Awards: 1939 Blonde, 1931 Dirigible, 1930 Rain or Shine, 1930 Ladies of Best Director for You Can't Take It with You (1938), 1937 Best Leisure, 1929 The Donovan Affair, 1928 The Power of the Press, Director for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), and 1935 Best 1928 Submarine, 1928 The Way of the Strong, 1928 The Matinee Director for It Happened One Night (1934). In 1982 he received Idol, 1928 So This Is Love?, 1928 That Certain Thing, 1927 For a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film the Love of Mike, 1926 The Strong Man, and 1922 The Ballad of Institute. Fisher's Boarding House. Capra directed 54 films, including 1961 Pocketful of Miracles, Capra also has 44 writing credits, including the screenplay of It’s 1959 A Hole in the Head, 1951 Here Comes the Groom, 1950 a Wonderful Life. -

Ellery Queen Master Detective

Ellery Queen Master Detective Ellery Queen was one of two brainchildren of the team of cousins, Fred Dannay and Manfred B. Lee. Dannay and Lee entered a writing contest, envisioning a stuffed‐shirt author called Ellery Queen who solved mysteries and then wrote about them. Queen relied on his keen powers of observation and deduction, being a Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson rolled into one. But just as Holmes needed his Watson ‐‐ a character with whom the average reader could identify ‐‐ the character Ellery Queen had his father, Inspector Richard Queen, who not only served in that function but also gave Ellery the access he needed to poke his nose into police business. Dannay and Lee chose the pseudonym of Ellery Queen as their (first) writing moniker, for it was only natural ‐‐ since the character Ellery was writing mysteries ‐‐ that their mysteries should be the ones that Ellery Queen wrote. They placed first in the contest, and their first novel was accepted and published by Frederick Stokes. Stokes would go on to release over a dozen "Ellery Queen" publications. At the beginning, "Ellery Queen" the author was marketed as a secret identity. Ellery Queen (actually one of the cousins, usually Dannay) would appear in public masked, as though he were protecting his identity. The buying public ate it up, and so the cousins did it again. By 1932 they had created "Barnaby Ross," whose existence had been foreshadowed by two comments in Queen novels. Barnaby Ross composed four novels about aging actor Drury Lane. After it was revealed that "Barnaby Ross is really Ellery Queen," the novels were reissued bearing the Queen name. -

Teacher Resource Guide

Teacher Resource Guide A Circle Theatre Company Production Produced by Erin Theriault Directed by Linda Novak Fridays, December 2 & 9 at 7:30pm. Saturdays, December 3 & 10 at 2:30pm and 7:30pm. Sundays, December 4 & 11 at 2:30pm educate | entertain | enrich Guide to the Guide With gratitude and appreciation to First Stage Theatre at www.Firststage.org for m uch of the content and spirit of this guide. Synopsis.............................................. 3 Meet the Characters……………….... 3 Our very best of the season to you and yours as you prepare to About the Author ............................... 4 enjoy Circle Theatre Company’s The Best Christmas Pageant Pre-Show Activities…….…………... 5 Ever, where the town’s absolute worst kids somehow steal the Recommended Reading….…………. 5 best parts in the annual church Christmas pageant! Amidst For Teachers: Curriculum connections trials and thievery, bullying and laughter, prejudice and tears, Before or after the play everyone learns a little something about the true meaning of Christmas. This year, our select Circle Theatre (High School) HISTORY Company invites the elementary-aged Circle Theatre Kids to Christmas Fast Facts………….…… 6 join us in presenting this much-loved classic. Christmas Pageants . ….…….. 15 Exploring the Christmas Story ….. 16-20 The enclosed Teacher Resource Guide is full of enrichment materials and activities spanning elementary and some middle LANGUAGE ARTS school. They were designed and / or compiled by First Stage Poetry: My Five Christmas Senses …. 7 Theatre and Circle Theatre Company to help educators and parents discover connections within the play. Benchmarks Christmas Traditions........................... 10 through 5th grade may be satisfied by much of what is within Carols from the Play ………………. -

Click Here to Read the Introductions by Rex Stout. TABLES of CONTENTS

Rex Stout Mystery Monthly (http://www.philsp.com/homeville/FMI/b201.htm#A3580) Launched to cash in on the success of the paperback editions of three Nero Wolfe novels, Rex Stout’s Mystery Monthly (initially under slightly different titles) was a digest‐sized mystery magazine combining classic reprints and some original material. Stout was listed as editor‐in‐chief, and contributed an introduction to each issue, but otherwise had little involvement. Click here to read the introductions by Rex Stout. Rex Stout Mystery Quarterly http://www.philsp.com/homeville/FMI/t3388.htm#A72295 http://www.philsp.com/homeville/FMI/t3388.htm#A72294 Publishers: o Avon Book Company; 119 West 57th Street, New York 13, NY: Rex Stout Mystery Quarterly Editors: o Louis Greenfield ‐ Editor: Rex Stout Mystery Quarterly TABLES OF CONTENTS (Rex Stout Mystery Quarterly [#1, May 1945] ed. Louis Greenfield (Avon Book Company, 25¢, 165pp, digest ifc. ∙ Introduction ∙ Rex Stout ∙ ed 11 ∙ Death and Company [The Continental Op] ∙ Dashiell Hammett ∙ ss Black Mask Nov 1930 19 ∙ Four Suspects [Jane Marple] ∙ Agatha Christie ∙ ss Pictorial Review Jan 1930 31 ∙ The Snake ∙ John Steinbeck ∙ ss The Monterey Beacon Jun 22 1935 40 ∙ The Rousing of Mr. Bradegar ∙ H. F. Heard ∙ ss The Great Fog and Other Weird Tales, Vanguard 1944 48 ∙ In the Library ∙ W. W. Jacobs ∙ ss Harper’s Monthly Jun 1901 56 ∙ Lawyer’s Fee ∙ H. Felix Valcoe ∙ ss Detective Fiction Weekly Oct 5 1940 68 ∙ Image in the Mirror [Lord Peter Wimsey] ∙ Dorothy L. Sayers ∙ nv Hangman’s Holiday, London: Gollancz 1933 89 ∙ Smart Guy ∙ Bruno Fischer ∙ ss 102 ∙ Black Orchids [Nero Wolfe; Archie Goodwin] ∙ Rex Stout ∙ na The American Magazine Aug 1941, as “Death Wears an Orchid” Rex Stout Mystery Quarterly [#2, August 1945] ed. -

Raptis Rare Books Holiday 2017 Catalog

1 This holiday season, we invite you to browse a carefully curated selection of exceptional gifts. A rare book is a gift that will last a lifetime and carries within its pages a deep and meaningful significance to its recipient. We know that each person is unique and it is our aim to provide expertise and service to assist you in finding a gift that is a true reflection of the potential owner’s personality and passions. We offer free gift wrapping and ship worldwide to ensure that your thoughtful gift arrives beautifully packaged and presented. Beautiful custom protective clamshell boxes can be ordered for any book in half morocco leather, available in a wide variety of colors. You may also include a personal message or gift inscription. Gift Certificates are also available. Standard shipping is free on all domestic orders and worldwide orders over $500, excluding large sets. We also offer a wide range of rushed shipping options, including next day delivery, to ensure that your gift arrives on time. Please call, email, or visit our expert staff in our gallery location and allow us to assist you in choosing the perfect gift or in building your own personal library of fine and rare books. Raptis Rare Books | 226 Worth Avenue | Palm Beach, Florida 33480 561-508-3479 | [email protected] www.RaptisRareBooks.com Contents Holiday Selections ............................................................................................... 2 History & World Leaders...................................................................................12 -

WED 5 SEP Home Home Box Office Mcr

THE DARK PAGESUN 5 AUG – WED 5 SEP home home box office mcr. 0161 200 1500 org The Killing, 1956 Elmore Leonard (1925 – 2013) The Killer Inside Me being undoubtedly the most Born in Dallas but relocating to Detroit early in his faithful. My favourite Thompson adaptation is Maggie A BRIEF NOTE ON THE GLOSSARY OF life and becoming synonymous with the city, Elmore Greenwald’s The Kill-Off, a film I tried desperately hard Leonard began writing after studying literature and to track down for this season. We include here instead FILM SELECTIONS FEATURED WRITERS leaving the navy. Initially working in the western genre Kubrick’s The Killing, a commissioned adaptation of in the 1950s (Valdez Is Coming, Hombre and Three- Lionel White’s Clean Break. The best way to think of this season is perhaps Here is a very brief snapshot of all the writers included Ten To Yuma were all filmed), Leonard switched to Raymond Chandler (1888 – 1959) in the manner of a music compilation that offers in the season. For further reading it is very much worth crime fiction and became one of the most prolific and a career overview with some hits, a couple of seeking out Into The Badlands by John Williams, a vital Chandler had an immense stylistic influence on acclaimed practitioners of the genre. Martin Amis and B-sides and a few lesser-known curiosities and mix of literary criticism, geography, politics and author American popular literature, and is considered by many Stephen King were both evangelical in their praise of his outtakes. -

The Secrets of Great Mystery Reading List

Below is a list of all (or nearly all!) of the books Professor Schmid mentions in his course The Secrets of Great Mystery and Suspense Fiction. Happy reading! • Megan Abbott, Die a Little; Queenpin; The End of Everything; Dare Me; The Fever • Pedro Antonio de Alarcón, “El Clavo” • Sherman Alexie, The Business of Fancydancing: Stories and Poems; The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven; Reservation Blues; Indian Killer • Margery Allingham, The Beckoning Lady • Rudolfo Anaya, Bless Me, Ultima; Zia Summer; Rio Grande Fall; Shaman Winter; Jemez Spring • Jakob Arjouni, Kismet; Brother Kemal • Paul Auster, City of Glass; Ghosts; The Locked Room • Robert Bloch, Psycho; The Scarf; The Dead Beat; Firebug • Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, She Who Was No More; The Living and the Dead • Jorge Luis Borges, “Death and the Compass” • Poppy Z. Brite, Exquisite Corpse • W.R. Burnett, Little Caesar • James M. Cain, Double Indemnity; The Postman Always Rings Twice • Paul Cain, Fast One • Andrea Camilleri, The Shape of Water • Truman Capote, In Cold Blood • Caleb Carr, The Alienist; The Italian Secretary: A Further Sherlock Holmes Adventure • John Dickson Carr, The Hollow Man • Vera Caspary, Laura; Bedelia • Raymond Chandler, “The Simple Art of Murder”; The Big Sleep; Farewell, My Lovely; The Long Goodbye; Playback • Agatha Christie, The Mysterious Affair at Styles; Murder on the Orient Express; The Body in the Library; The Murder at the Vicarage; The Murder of Roger Ackroyd; Death on the Nile; The ABC Murders; Partners in Crime; The Secret Adversary;