Capital Flows and Exchange Rate Volatility: Singapore's Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore Exchange Limited

18 October 2016 Asia Pacific/Singapore Equity Research Diversified Financial Services Singapore Exchange Limited (SGXL.SI / SGX SP) Rating NEUTRAL Price (14 Oct 16, S$) 7.25 INITIATION Target price (S$) 7.60 Upside/downside (%) 4.8 Mkt cap (S$/US$ mn) 7,769 / 5,589 Lacks near-term catalysts Enterprise value (S$ mn) 6,887 Number of shares (mn) 1,072 ■ We initiate coverage on Singapore Exchange with a NEUTRAL rating Free float (%) 71.3 and target price of S$7.60. The key investment case for SGX is longer-term 52-wk price range (S$) 8.05-6.65 ADTO-6M (US$ mn) 10.3 growth through both equities and success in its strategy to become an Asian *Stock ratings are relative to the relevant country benchmark. regional gateway, with derivatives being the medium-term driver, in our view. ¹Target price is for 12 months. Nearer-term, its fortunes are more linked to the current level of market activity, Research Analysts which remains uninspiring, with a risk of further seasonal slowdown in 4Q. Rikin Shah 65 6212 3098 ■ Securities business remains subdued. Securities turnover and revenue hit [email protected] the decade low in FY16. The subdued turnover is mainly a result of declining velocity (peak-to-date -43%), but a dearth of IPOs and an increase in privatisation deals have further exacerbated the situation. We discuss a few structural drivers like higher free float and high frequency trading, which could improve velocity in the long term. ■ Derivatives growth secular and less volatile. Derivatives' revenue growth of 18% CAGR in the past five years has been a great stabiliser—more than offsetting a 7% fall in securities revenue. -

Sanli Bags New Contracts in Singapore and Myanmar; Boosts Order Book to S$198.0 Million

SANLI ENVIRONMENTAL LIMITED MEDIA RELEASE For Immediate Release Sanli bags new contracts in Singapore and Myanmar; boosts order book to S$198.0 million S$7.8 million O&M contract wins from the Singapore Public Utilities Board reflects the continued confidence the public sector has in the Group’s capabilities Expansion into Myanmar is progressing well, as the Group secures EPC contracts worth approximately S$4.3 million Order book stands at S$198.0 million SINGAPORE, 2 April 2019 – Sanli Environmental Limited (“Sanli” and together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”), one of Singapore’s leading environmental engineering companies, is pleased to announce that it has recently secured new contracts (“Contracts”) in Singapore and Myanmar, worth a total of approximately S$12.1 million. With these contract wins, the Group’s order book stands at S$198.0 million. These new contracts are expected to contribute to Sanli’s revenue from the financial year ending 31 March 2020 (“FY2020”). The Operations and Maintenance (“O&M”) contracts are awarded by the Singapore Public Utilities Board (“PUB”). Spanning over a period of three years from March 2019, Sanli will be involved in the refurbishment of centrifugal pumps in the NEWater Factories and Waterworks, the overhaul of centrifugal pumps, disintegrators and related equipment and maintenance works at various PUB installations, as well as the maintenance of electrical equipment at the Johor Plants. Sanli had also secured two Engineering, Procurement and Construction (“EPC”) contracts from the Myanmar government, worth a total of 4.9 billion Myanmar Kyat (Ks) or SANLI ENVIRONMENTAL LIMITED approximately S$4.3 million. -

Evidence from the Singapore Stock Market Q

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Journal of Banking & Finance 32 (2008) 2205–2219 www.elsevier.com/locate/jbf How does the call market method affect price efficiency? Evidence from the Singapore Stock Market q Rosita P. Chang a, S. Ghon Rhee a,b, Gregory R. Stone c, Ning Tang d,* a Shidler College of Business, University of Hawaii, 2404 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822-2282, USA b Sung Kyun Kwan University Business School, Seoul, South Korea c College of Business Administration, University of Nevada, Reno, Mail Stop 028, Reno, NV 89557, USA d School of Business and Economics, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, ON, Canada N2L 3C5 Received 23 November 2006; accepted 27 December 2007 Available online 12 January 2008 Abstract On August 21, 2000, the Singapore Exchange (SGX) adopted the call market method to open and close the market while the remain- der of the day’s trading continued to rely on the continuous auction method. The call method significantly improved the price discovery process and market quality. A positive spillover effect is observed from the opening and closing calls. Day-end price manipulation also declined after the introduction of the call market method. However, the beneficial impact from the call market method is asymmetric, benefiting liquid stocks more than illiquid stocks. Ó 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. JEL classification: G14; G15; G18 Keywords: Market mechanism; Call method; Price efficiency; Trading noise; Return reversals; Price manipulation; Singapore Exchange 1. Introduction tion which interacts with the existing quote-driven trading mechanism and subsequently introduced an opening call Schwartz (2000) correctly predicted that with advances auction later that same year. -

N7 Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) Connectivity Access BSE Via the N7 Network

Market Data + Services N7 Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) Connectivity Access BSE via the N7 Network Deutsche Börse’s partnership with the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) sees the BSE leverage N7’s Benefi ts network connectivity between India and Deutsche Low latency connectivity between Hong Kong, Börse access points in Hong Kong and Singapore. Singapore and BSE data centres As a result, participants of BSE are able to benefit Carrier-resilient connection to BSE with from Deutsche Börse’s resilient and low latency N7 dedicated, guaranteed 2Mbps bandwidth network to connect to BSE data centres in India. Continuous network monitoring of lines during BSE operating hours Improved access to Indian fi nancial markets BSE market feed and interactive data available The low latency N7 network offers a secure connection between your trading premises and the BSE, the world’s biggest stock exchange by number N7 network advantages of listed companies. BSE has also implemented Trade on BSE’s markets for equities, equity Deutsche Börse’s state-of-the-art trading system derivatives and currency derivatives. – the Eurex T7 Platform – across all trading segments Access additional markets such as the SIX Swiss and is the fastest Exchange in India with trading Exchange, the Singapore Exchange and the Central & system processing times as low as 200 µs. Eastern European Stock Exchange Group (CEESEG) over one physical line, leveraging the use of existing Faster connectivity from Hong Kong and Singapore network infrastructure and hardware components Market participants can now connect their Hong Work with a single contractual partner, well Kong and Singapore-based trade execution systems established and experienced in network operations to BSE’s fully regulated offering covering equities, and specialised in financial technology equity derivatives and currency derivatives. -

JES INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS LIMITED (Company Registration No

JES INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS LIMITED (Company Registration No. 200604831K) (Incorporated in the Republic of Singapore) PROPOSED PLACEMENT OF UP TO 42,000,000 NEW ORDINARY SHARES IN THE CAPITAL OF JES INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS LIMITED (THE “PLACEMENT”) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 1. INTRODUCTION The Board of Directors of JES International Holdings Limited (the “Company”) refer to the Company’s announcement dated 4 March 2014 whereby each of Merlion Capital Pte Ltd, Mr Lee Loi Sing, YA Global Master SPV and Mr Yin Xiangdong will, pursuant to the Placement Agreements dated 3 March 2014 (the “Previous Placement Agreements”), be allotted 23,000,000, 12,000,000, 8,000,000, and 7,000,000 new ordinary shares respectively, at S$0.14463 per share (the “Previous Subscription Price”). The Previous Subscription Price under the Previous Placement Agreements represents a discount of more than 10% to the weighted average price of the Company’s ordinary shares for trades done on the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited (“SGX-ST”) for the full market day on 27 February 2014 (being the last full market day immediately preceding the date on which the Previous Placement Agreement was signed) up to the trading halt which was called by the Company on 28 February 2014 at 1315 hrs. As such, the Company, Merlion Capital Pte Ltd, Mr Lee Loi Sing, YA Global Master SPV and Mr Yin Xiangdong have agreed to terminate the Previous Placement Agreements without any further cost or claim and demands whatsoever -

Enhancing Liquidity in Emerging Market Exchanges

ENHANCING LIQUIDITY IN EMERGING MARKET EXCHANGES ENHANCING LIQUIDITY IN EMERGING MARKET EXCHANGES OLIVER WYMAN | WORLD FEDERATION OF EXCHANGES 1 CONTENTS 1 2 THE IMPORTANCE OF EXECUTIVE SUMMARY GROWING LIQUIDITY page 2 page 5 3 PROMOTING THE DEVELOPMENT OF A DIVERSE INVESTOR BASE page 10 AUTHORS Daniela Peterhoff, Partner Siobhan Cleary Head of Market Infrastructure Practice Head of Research & Public Policy [email protected] [email protected] Paul Calvey, Partner Stefano Alderighi Market Infrastructure Practice Senior Economist-Researcher [email protected] [email protected] Quinton Goddard, Principal Market Infrastructure Practice [email protected] 4 5 INCREASING THE INVESTING IN THE POOL OF SECURITIES CREATION OF AN AND ASSOCIATED ENABLING MARKET FINANCIAL PRODUCTS ENVIRONMENT page 18 page 28 6 SUMMARY page 36 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Trading venue liquidity is the fundamental enabler of the rapid and fair exchange of securities and derivatives contracts between capital market participants. Liquidity enables investors and issuers to meet their requirements in capital markets, be it an investment, financing, or hedging, as well as reducing investment costs and the cost of capital. Through this, liquidity has a lasting and positive impact on economies. While liquidity across many products remains high in developed markets, many emerging markets suffer from significantly low levels of trading venue liquidity, effectively placing a constraint on economic and market development. We believe that exchanges, regulators, and capital market participants can take action to grow liquidity, improve the efficiency of trading, and better service issuers and investors in their markets. The indirect benefits to emerging market economies could be significant. -

List of Execution Venues Made Available by Societe Generale

List of Execution Venues made available by Societe Generale January 2018 Note that this list of Execution Venues is not exhaustive and will be kept under review and updated in accordance with Societe Generale’s execution practices. Societe Generale reserves the right to use other Execution Venues in addition to those listed below where it deems it appropriate in accordance with execution practices. Where Societe Generale acts as the Execution Venue, it will consider all sources of reasonably available information to obtain the best possible outcome. Fixed Income . The main Execution Venue is Societe Generale SA (and its affiliates) . When the trading obligation for derivatives applies, execution will take place on MiFID trading venues (Regulated Markets, or MTF or OTF or all equivalent venues as SEF) Alternative Venues include: BGC Bloomberg Bloomberg FIET Brokertec GFI Marketaxess MTP MTS TP ICAP Tradeweb Tradition Forex . The main Execution Venue is Societe Generale SA (and its affiliates) Alternative Venues include: 360T Alpha BGC Bloomberg Currenex EBS Equilend FX Connect FX Spotstream FXall Hotpspot ICAP Integral FX inside Reuters Tradertools Cash Equities Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange EDGEA Exchange NYSE Amex Alpha EDGEX Exchange NYSE Arca AlphaY EDGX NYSE Stock Exchange Aquis Equilend Omega ARCA Stocks Euronext Amsterdam OMX Copenhagen ASX Centre Point Euronext Block OMX Helsinki Athens Stock Exchange Euronext Brussels OMX Stockholm ATHEX Euronext Cash Amsterdam OneChicago Australia Securities Exchange Euronext Cash Brussels Oslo -

Discussion Paper on Stock Exchange Demutualization

Discussion Paper on Stock Exchange Demutualization IOSCO Technical Committee Consultation Draft December, 2000 Consultation Draft International Organization of Securities Commissions Discussion Paper on Stock Exchange Demutualization The Technical Committee (the Committee) of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) has been discussing certain changes that are taking place in the stock exchange industry, particularly the trend towards stock exchanges becoming for- profit enterprises and the increase in competition among exchanges and other electronic networks. The Committee has prepared a discussion paper setting out some of the issues raised and is seeking the views of interested parties on these matters. The discussion paper provides some background to the changes, particularly those regarding the transformation of exchanges into for-profit shareholder-owned companies, which is referred to as demutualization. The paper then canvases issues that these changes raise and notes some responses that have been taken by various IOSCO member jurisdictions. The key regulatory issue is whether these changes will undermine the commitment of resources and capabilities by a stock exchange to effectively fulfil its regulatory and public interest responsibilities at an appropriate standard. The regulatory questions and concerns identified fall into three areas.: a. What conflicts of interest are created or increased where a for-profit entity also performs the regulatory functions that an exchange might have regarding: i) primary market regulation (listing and admission of companies, self- listing); ii) secondary market regulation (trading rules); and iii) member regulation? b. A fair and efficient capital market is a public good. A well-run exchange is a key part of the capital market. -

A Leading Financial Markets Infrastructure and Data Provider

A leading financial markets infrastructure and data provider London Stock Exchange Group plc Annual Report 2020 Our purpose Driving financial stability, empowering economies and enabling customers to create sustainable growth. Our vision As a leading financial markets infrastructure and data provider, we want to shape the future of our industry to serve our customers and markets better. Further information on London Stock Exchange Group can be found at: www.lseg.com London Stock Exchange Group plc 10 Paternoster Square London EC4M 7LS Telephone: +44 (0)20 7797 1000 Registered in England and Wales No. 5369106 ABOUT LSEG PLC CONTENTS LSEG (London Stock Exchange Group) is Strategic Report more than a diversified global financial Sign-off for the Strategic Report is provided in markets infrastructure and data business. the Directors’ Report on page 124. We are dedicated, open-access partners with a commitment to excellence in delivering the Chair’s statement 2 services our customers expect from us. With Chief Executive Officer’s statement 4 extensive experience, deep knowledge and What we do – our business model 8 worldwide presence across financial markets, Overview of Group activities 12 we enable businesses and economies around Our strategy 14 the world to fund innovation, manage risk and Market trends and our response 16 create jobs. It’s how we’ve contributed to Principal risks and uncertainties 24 supporting the financial stability and growth Executive Management Team 40 of communities and economies globally for more than 300 years. Strategic Report: 2020 Review Highlights 43 LOOKING FORWARD Financial Review 44 Supporting Sustainable Growth 54 In January 2021, LSEG completed the Board engagement with stakeholders 68 acquisition of Refinitiv, which transforms the Compliance with section 172(1) 70 size, scale and range of our business activities. -

Singapore Exchange Study Tour 28 October – 1 November 2008

Singapore Exchange Study Tour 28 October – 1 November 2008 Submitted by: A delegation of postgraduate students, Lee Shau Kee School of Business and Administration, The Open University of Hong Kong Table of Contents Description page 1 Introduction 3 2 Acknowledgement 4 3 Objectives Expected and Achieved 4 4 Itinerary of Activities 5 5 Visits to Organizations 6 5.1 SIM University 6 5.2 Housing & Development Board (HDB) 8 5.3 NEWater Visit Centre 9 5.4 Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) 11 5.5 Jurong Town Corporation (JTC) 12 5.6 Singapore Airlines (SIA) 14 5.7 Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) 16 6 Cultural Visits 16 6.1 The Merlion 16 6.2 Chinatown 17 6.3 Little India 17 7 Conclusion 18 Appendix I: Personal Sharings from Delegates 20 2 1. Introduction Media have been accustomed to place Singapore and Hong Kong as rivals. While both cities are small in size and have very limited resources, they play a significant role in the international stage of different sectors, as a centre of finance, logistics, services and as a gateway connecting the West to the East. This race has always been tight and trophies change hands between the two. In the 2008-2009 Global Competitiveness Report, Singapore surpasses Hong Kong in ranking. And the race just goes on. This five-day Study Tour Visit (28 Oct – 1 Nov 2008) to Singapore organized by Lee Shau Kee School of Business and Administration with the assistance from the MBA Student Association of The Open University of Hong Kong has given us a very unique opportunity to take a closer look at Singapore through different angles and perspectives trying to unveil her ambition and strategies in positioning the country as the regional commanding height. -

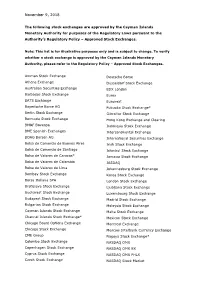

The List of Approved Stock Exchanges

November 9, 2018 The following stock exchanges are approved by the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority for purposes of the Regulatory Laws pursuant to the Authority’s Regulatory Policy – Approved Stock Exchanges. Note: This list is for illustrative purposes only and is subject to change. To verify whether a stock exchange is approved by the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority, please refer to the Regulatory Policy – Approved Stock Exchanges. Amman Stock Exchange Deutsche Borse Athens Exchange Dusseldorf Stock Exchange Australian Securities Exchange EDX London Barbados Stock Exchange Eurex BATS Exchange Euronext Bayerische Borse AG Fukuoka Stock Exchange* Berlin Stock Exchange Gibraltar Stock Exchange Bermuda Stock Exchange Hong Kong Exchange and Clearing BM&F Bovespa Indonesia Stock Exchange BME Spanish Exchanges Intercontinental Exchange BOAG Borsen AG International Securities Exchange Bolsa de Comercio de Buenos Aires Irish Stock Exchange Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago Istanbul Stock Exchange Bolsa de Valores de Caracas* Jamaica Stock Exchange Bolsa de Valores de Colombia JASDAQ Bolsa de Valores de Lima Johannesburg Stock Exchange Bombay Stock Exchange Korea Stock Exchange Borsa Italiana SPA London Stock Exchange Bratislava Stock Exchange Ljubljana Stock Exchange Bucharest Stock Exchange Luxembourg Stock Exchange Budapest Stock Exchange Madrid Stock Exchange Bulgarian Stock Exchange Malaysia Stock Exchange Cayman Islands Stock Exchange Malta Stock Exchange Channel Islands Stock Exchange* Mexican Stock Exchange Chicago Board Options Exchange -

Mandatory Provident Fund Schemes Authority Iii.4

Guidelines III.4 MANDATORY PROVIDENT FUND SCHEMES AUTHORITY III.4 Guidelines on Approved Exchanges INTRODUCTION Section 2 of the Mandatory Provident Fund Schemes (General) Regulation (“the Regulation”) defines “approved stock exchange” to mean: (a) a recognized stock market; or (b) any stock exchange established in a place outside Hong Kong that is declared by the Authority by notice published in the Gazette to be an approved stock exchange for the purposes of this Regulation. 2. Section 2 of the Regulation also defines “approved futures exchange” to mean: (a) a recognized futures market; or (b) any futures exchange established in a place outside Hong Kong that is declared by the Authority by notice published in the Gazette to be an approved futures exchange for the purposes of this Regulation. 3. Section 6H of the Mandatory Provident Fund Schemes Ordinance (“the Ordinance”) provides that the Authority may issue guidelines for the guidance of approved trustees, service providers and other persons concerned with the Ordinance. 4. The Authority hereby issues guidelines to: (a) set out the names of the stock exchanges established in a place Version 3 – May 2003 Page 1 Guidelines III.4 outside Hong Kong which have been declared by the Authority to be approved stock exchanges for the purposes of section 2 of the Regulation; and (b) set out the names of the futures exchanges established in a place outside Hong Kong which have been declared by the Authority to be approved futures exchanges for the purposes of section 2 of the Regulation. APPROVED EXCHANGES 5. The lists of approved stock exchanges and approved futures exchanges established in a place outside Hong Kong are set out in Annexes A and B respectively.