From Callas to Netrebko: Diva Power, Vocality, and the Mediatisation of the Operatic Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

10-12-2019 Turandot Mat.Indd

Synopsis Act I Legendary Peking. Outside the Imperial Palace, a mandarin reads an edict to the crowd: Any prince seeking to marry Princess Turandot must answer three riddles. If he fails, he will die. The most recent suitor, the Prince of Persia, is to be executed at the moon’s rising. Among the onlookers are the slave girl Liù, her aged master, and the young Calàf, who recognizes the old man as his long-lost father, Timur, vanquished King of Tartary. Only Liù has remained faithful to the king, and when Calàf asks her why, she replies that once, long ago, Calàf smiled at her. The mob cries for blood but greets the rising moon with a sudden fearful reverence. As the Prince of Persia goes to his death, the crowd calls upon the princess to spare him. Turandot appears in her palace and wordlessly orders the execution to proceed. Transfixed by the beauty of the unattainable princess, Calàf decides to win her, to the horror of Liù and Timur. Three ministers of state, Ping, Pang, and Pong, appear and also try to discourage him, but Calàf is unmoved. He reassures Liù, then strikes the gong that announces a new suitor. Act II Within their private apartments, Ping, Pang, and Pong lament Turandot’s bloody reign, hoping that love will conquer her and restore peace. Their thoughts wander to their peaceful country homes, but the noise of the crowd gathering to witness the riddle challenge calls them back to reality. In the royal throne room, the old emperor asks Calàf to reconsider, but the young man will not be dissuaded. -

In Santa Cruz This Summer for Special Summer Encore Productions

Contact: Peter Koht (831) 420-5154 [email protected] Release Date: Immediate “THE MET: LIVE IN HD” IN SANTA CRUZ THIS SUMMER FOR SPECIAL SUMMER ENCORE PRODUCTIONS New York and Centennial, Colo. – July 1, 2010 – The Metropolitan Opera and NCM Fathom present a series of four encore performances from the historic archives of the Peabody Award- winning The Met: Live in HD series in select movie theaters nationwide, including the Cinema 9 in Downtown Santa Cruz. Since 2006, NCM Fathom and The Metropolitan Opera have partnered to bring classic operatic performances to movie screens across America live with The Met: Live in HD series. The first Live in HD event was seen in 56 theaters in December 2006. Fathom has since expanded its participating theater footprint which now reaches more than 500 movie theaters in the United States. We’re thrilled to see these world class performances offered right here in downtown Santa Cruz,” said councilmember Cynthia Mathews. “We know there’s a dedicated base of local opera fans and a strong regional audience for these broadcasts. Now, thanks to contemporary technology and a creative partnership, the Metropolitan Opera performances will become a valuable addition to our already stellar lineup of visual and performing arts.” Tickets for The Met: Live in HD 2010 Summer Encores, shown in theaters on Wednesday evenings at 6:30 p.m. in all time zones and select Thursday matinees, are available at www.FathomEvents.com or by visiting the Regal Cinema’s box office. This summer’s series will feature: . Eugene Onegin – Wednesday, July 7 and Thursday, July 8– Soprano Renée Fleming and baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky star in Tchaikovsky’s lushly romantic masterpiece about mistimed love. -

Diva Forever the Operatic Voice Between Reproduction and Reception

ERIK STEINSKOG Diva Forever The Operatic Voice between Reproduction and Reception The operatic voice has been among the key dimensions within opera-studies for several years. Within a fi eld seemingly reinventing itself, however, this voice is intimately relat- ed to other dimensions: sound, the body, gender and sexuality, and so forth. One par- ticular voice highlighting these intersections is the diva’s voice. Somewhat paradoxical this is not least the case when this particular voice is recorded, stored, and replayed by way of technology. The technologically reproduced voice makes it possible to fully con- centrate on “the voice itself,” seemingly without paying any attention to other dimen- sions. The paradox thus arises that the above-mentioned intersections might be most clearly found when attempts are made to remove them from the scene of perception. The focus on “the voice itself” is familiar to readers of Michel Chion’s The Voice in Cinema. Starting out with stating that the voice is elusive, Chion asks what is left when one eliminates, from the voice, “everything that is not the voice itself.”1 Relating pri- marily to fi lm, and coming from a strong background in psychoanalysis, Chion moves on to discuss many features of the voice, beginning with the sometimes forgotten dif- ferentiation from speech. The materiality of the voice becomes important, and then already different intersections are hinted at. Combining Chion’s interpretations with musicology is nothing new, but it opens some other questions. The voice in music is not necessarily as elusive as Chion seems to argue, or, perhaps better, its elusiveness is of a different kind.2 And when it comes to the operatic voice, dimensions beyond the ones Chion discusses beckon a refl ection. -

Season 2014-2015

27 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, May 7, at 8:00 Friday, May 8, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, May 9, at 8:00 Cristian Măcelaru Conductor Sarah Chang Violin Ligeti Romanian Concerto I. Andantino— II. Allegro vivace— III. Adagio ma non troppo— IV. Molto vivace First Philadelphia Orchestra performances Beethoven Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21 I. Adagio molto—Allegro con brio II. Andante cantabile con moto III. Menuetto (Allegro molto e vivace)—Trio— Menuetto da capo IV. Adagio—Allegro molto e vivace Intermission Dvořák Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53 I. Allegro ma non troppo—Quasi moderato— II. Adagio ma non troppo—Più mosso—Un poco tranquillo, quasi tempo I III. Finale: Allegro giocoso ma non troppo Enescu Romanian Rhapsody in A major, Op. 11, No. 1 This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. The May 7 concert is sponsored by MedComp. The May 8 and 9 concerts are sponsored by the Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation. designates a work that is part of the 40/40 Project, which features pieces not performed on subscription concerts in at least 40 years. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 228 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world, renowned for its distinctive sound, desired for its keen ability to capture the hearts and imaginations of audiences, and admired for a legacy of imagination and innovation on and off the concert stage. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

1718Studyguidetosca.Pdf

TOSCA An opera in three acts by Giocomo Puccini Text by Giacosa and Illica after the play by Sardou Premiere on January 14, 1900, at the Teatro Constanzi, Rome OCTOBER 5 & 7, 2O17 Andrew Jackson Hall, TPAC The Patricia and Rodes Hart Production Directed by John Hoomes Conducted by Dean Williamson Featuring the Nashville Opera Orchestra CAST & CHARACTERS Floria Tosca, a celebrated singer Jennifer Rowley* Mario Cavaradossi, a painter John Pickle* Baron Scarpia, chief of police Weston Hurt* Cesare Angelotti, a political prisoner Jeffrey Williams† Sacristan/Jailer Rafael Porto* Sciarrone, a gendarme Mark Whatley† Spoletta, a police agent Thomas Leighton* * Nashville Opera debut † Former Mary Ragland Young Artist TICKETS & INFORMATION Contact Nashville Opera at 615.832.5242 or visit nashvilleopera.org. Study Guide Contributors Anna Young, Education Director Cara Schneider, Creative Director THE STORY SETTING: Rome, 1800 ACT I - The church of Sant’Andrea della Valle quickly helps to conceal Angelotti once more. Tosca is immediately suspicious and accuses Cavaradossi of A political prisoner, Cesare Angelotti, has just escaped and being unfaithful, having heard a conversation cease as she seeks refuge in the church, Sant’Andrea della Valle. His sis - entered. After seeing the portrait, she notices the similari - ter, the Marchesa Attavanti, has often prayed for his release ties between the depiction of Mary Magdalene and the in the very same chapel. During these visits, she has been blonde hair and blue eyes of the Marchesa Attavanti. Tosca, observed by Mario Cavaradossi, the painter. Cavaradossi who is often unreasonably jealous, feels her fears are con - has been working on a portrait of Mary Magdalene and the firmed at the sight of the painting. -

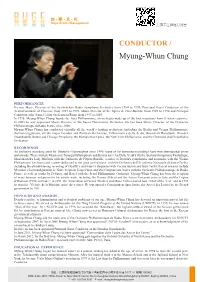

Myung-Whun Chung

如 • 歌 • 文 • 化 Ruge Artists Management 扫描关注微信订阅号 CONDUCTOR / Myung-Whun Chung PERFORMANCES He was Music Director of the Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra from 1984 to 1990, Principal Guest Conductor of the TeatroComunale of Florence from 1987 to 1992, Music Director of the Opéra de Paris-Bastille from 1989 to 1994 and Principal Conductor atthe Santa Cecilia Orchestra in Rome from 1997 to 2005. In 1995, Myung-Whun Chung founds the Asia Philharmonic, an orchestra made up of the best musicians from 8 Asian countries. In 2005,he was appointed Music Director of the Seoul Philarmonic Orchestra. He has been Music Director of the Orchestre Philharmonique deRadio France since 2000. Myung-Whun Chung has conducted virtually all the world’s leading orchestras, including the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic, theConcertgebouw, all the major London and Parisian Orchestras, Filharmonica della Scala, Bayerisch Rundfunk, Dresden Staatskapelle,Boston and Chicago Symphony, the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland and Philadelphia Orchestras. RECORDINGS An exclusive recording artist for Deutsche Grammophon since 1990, many of his numerous recordings have won international prizes and awards. These include Messiaen's TurangalîlaSymphony and Eclairs sur l’Au-Delà, Verdi's Otello, Berlioz'sSymphonie Fantastique, Shostakovich's Lady Macbeth with the Orchestre de l'Opéra Bastille; a series of Dvorák's symphonies and serenades with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and a series dedicated to the great sacred music with the Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, including the award-winning recording of Duruflé’s and Fauré’s Requiems with Cecilia Bartoli and Bryn Terfel. Recent releases include Messiaen’s La transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ and Des Canyons aux étoiles with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France as well as works by Debussy and Ravel with the Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon.