Toward General Congregation 34

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Release 3.5.3

Ex Falso / Quod Libet Release 3.5.3 February 02, 2016 Contents 1 Table of Contents 3 i ii Ex Falso / Quod Libet, Release 3.5.3 Note: There exists a newer version of this page and the content below may be outdated. See https://quodlibet.readthedocs.org/en/latest for the latest documentation. Quod Libet is a GTK+-based audio player written in Python, using the Mutagen tagging library. It’s designed around the idea that you know how to organize your music better than we do. It lets you make playlists based on regular expressions (don’t worry, regular searches work too). It lets you display and edit any tags you want in the file, for all the file formats it supports. Unlike some, Quod Libet will scale to libraries with tens of thousands of songs. It also supports most of the features you’d expect from a modern media player: Unicode support, advanced tag editing, Replay Gain, podcasts & Internet radio, album art support and all major audio formats - see the screenshots. Ex Falso is a program that uses the same tag editing back-end as Quod Libet, but isn’t connected to an audio player. If you’re perfectly happy with your favorite player and just want something that can handle tagging, Ex Falso is for you. Contents 1 Ex Falso / Quod Libet, Release 3.5.3 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Table of Contents Note: There exists a newer version of this page and the content below may be outdated. See https://quodlibet.readthedocs.org/en/latest for the latest documentation. -

Address of Pope Paul VI to General Congregation 32 (1974)

Address of Pope Paul VI to General Congregation 32 (1974) Pope Paul VI addressed the delegates to the 32nd General Congregation on December 3, 1974, noting similar “joy and trepidation” to when the last congregation began nearly a decade before. Looking to the assembled Jesuits, the pontiff declares, “there is in you and there is in us the sense of a moment of destiny for your Society.” Indeed, “in this hour of anxious expectation and of intense attention ‘to what the Spirit is saying’ to you and to us,” Paul VI asks the delegates to answer: “Where do you come from?” “Who are you?” “Where are you going?” Esteemed and beloved Fathers of the Society of Jesus, As we receive you today, there is renewed for us the joy and trepidation of May 7, 1965, when the Thirty-first General Congregation of your Society began, and that of November 15 of the following year, at its conclusion. We have great joy because of the outpouring of sincere paternal love which every meeting between the Pope and the sons of St. Ignatius cannot but stir up. This is especially true because we see the witness of Christian apostolate and of fidelity which you give us and in which we rejoice. But there is also trepidation for the reasons of which we shall presently speak to you. The inauguration of the 32nd General Congregation is a special event, and it is usual for us to have such a meeting on an occasion like this; but this meeting has a far wider and more historic significance. -

Book Reviews ∵

journal of jesuit studies 4 (2017) 99-183 brill.com/jjs Book Reviews ∵ Thomas Banchoff and José Casanova, eds. The Jesuits and Globalization: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Challenges. Washington, dc: Georgetown University Press, 2016. Pp. viii + 299. Pb, $32.95. This volume of essays is the outcome of a three-year project hosted by the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University which involved workshops held in Washington, Oxford, and Florence and cul- minated in a conference held in Rome (December 2014). The central question addressed by the participants was whether or not the Jesuit “way of proceeding […] hold[s] lessons for an increasingly multipolar and interconnected world” (vii). Although no fewer than seven out of the thirteen chapters were authored by Jesuits, the presence amongst them of such distinguished scholars as John O’Malley, M. Antoni Üçerler, Daniel Madigan, David Hollenbach, and Francis Clooney as well as of significant historians of the Society such as Aliocha Mal- davsky, John McGreevy, and Sabina Pavone together with that of the leading sociologist of religion, José Casanova, ensure that the outcome is more than the sum of its parts. Banchoff and Casanova make it clear at the outset: “We aim not to offer a global history of the Jesuits or a linear narrative of globaliza- tion but instead to examine the Jesuits through the prism of globalization and globalization through the prism of the Jesuits” (2). Accordingly, the volume is divided into two, more or less equal sections: “Historical Perspectives” and “Contemporary Challenges.” In his sparklingly incisive account of the first Jesuit encounters with Japan and China, M. -

English Songs

English Songs 18000 04 55-Vũ Luân-Thoại My 18001 1 2 3-Gloria Estefan 18002 1 Sweet Day-Mariah Carey Boyz Ii M 18003 10,000 Promises-Backstreet Boys 18004 1999-Prince 18005 1everytime I Close My Eyes-Backstr 18006 2 Become 1-Spice Girls 18007 2 Become 1-Unknown 18008 2 Unlimited-No Limit 18009 25 Minutes-Michael Learns To Rock 18010 25 Minutes-Unknown 18011 4 gio 55-Wynners 18012 4 Seasons Of Lonelyness-Boyz Ii Me 18013 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover-Paul S 18014 500 Miles Away From Home-Peter Pau 18015 500 Miles-Man 18016 500 Miles-Peter Paul-Mary 18017 500 Miles-Unknown 18018 59th Street Bridge Song-Classic 18019 6 8 12-Brian McKnight 18020 7 Seconds-Unknown 18021 7-Prince 18022 9999999 Tears-Unknown 18023 A Better Love Next Time-Cruise-Pa 18024 A Certain Smile-Unknown 18025 A Christmas Carol-Jose Mari Chan 18026 A Christmas Greeting-Jeremiah 18027 A Day In The Life-Beatles-The 18028 A dear John Letter Lounge-Cardwell 18029 A dear John Letter-Jean Sheard Fer 18030 A dear John Letter-Skeeter Davis 18031 A dear Johns Letter-Foxtrot 18032 A Different Beat-Boyzone 18033 A Different Beat-Unknown 18034 A Different Corner-Barbra Streisan 18035 A Different Corner-George Michael 18036 A Foggy Day-Unknown 18037 A Girll Like You-Unknown 18038 A Groovy Kind Of Love-Phil Collins 18039 A Guy Is A Guy-Unknown 18040 A Hard Day S Night-The Beatle 18041 A Hard Days Night-The Beatles 18042 A Horse With No Name-America 18043 À La Même Heure Dans deux Ans-Fema 18044 A Lesson Of Love-Unknown 18045 A Little Bit Of Love Goes A Long W- 18046 A Little Bit-Jessica -

Following the Way of Ignatius, Francis Xavier and Peter Faber,Servants Of

FOLLOWING THE WAY OF IGNATIUS, FRANCIS XAVIER AND PETER FABER, SERVANTS OF CHRIST’S MISSION* François-Xavier Dumortier, S.J. he theme of this meeting places us in the perspective of the jubilee year, which recalls to us the early beginnings of the Society of Jesus. What is the aim of thisT jubilee year? It is not a question simply of visiting the past as one does in a museum but of finding again at the origin of our history, that Divine strength which seized some men – those of yesterday and us today – to make them apostles. It is not even a question of stopping over our beginnings in Paris, in 1529, when Ignatius lodged in the same room with Peter Faber and Francis-Xavier: it is about contemplating and considering this unforeseeable and unexpected meeting where this group of companions, who became so bonded together by the love of Christ and for “the sake of souls”, was born by the grace of God. And finally it is not a question of reliving this period as if we were impelled solely by an intellectual curiosity, or by a concern to give an account of our history; it is about rediscovering through Ignatius, Francis-Xavier and Peter Faber this single yet multiple face of the Society, those paths that are so vibrantly personal and their common, resolute desire to become “companions of Jesus”, to be considered “servants” of The One who said, “I no longer call you servants… I call you friends” (Jn. 15,15) Let us look at these three men so very different in temperament that everything about them should have kept them apart one from another – but also so motivated by the same desire to “search and find God”. -

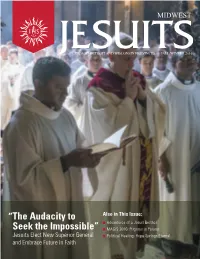

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr. -

Jesuits Elect 31St Superior General of the Society of Jesus

Quarterly newsletter forU friends of the Oregon PDATE Province Winter 2016 Oregon Provincial Fr. Scott Santarosa, SJ, with the New Superior General Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ. Jesuits Elect 31st Superior General of the Society of Jesus In this issue: Father Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, of Venezuela was elected the 31st Superior General of the Society of Jesus at the Jesuits’ General Congregation 36 (GC 36) in Rome on October 14. Fr. p. 2 Letter from the Sosa is the first Latin American Superior General of the Society of Jesus, the largest religious Provincial order of priests and brothers in the Catholic Church. Fr. Sosa, Delegate of the General for the International Houses and Works of the Society of In Memoriam Jesus in Rome, was elected by 212 Jesuit electors at the General Congregation, the supreme p. 3 governing body of the Society, held at the Jesuit Curia, the Society’s headquarters in Rome. News from Around He succeeds Father Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, 80, who resigned as planned after serving as Superior p. 6 the Province General since 2008. “Fr. Sosa strikes me as a man who is imminently comfortable in his skin, as easy to be Letter from the around as your next door neighbor, and whose way of being immediately puts you at ease,” p. 8 Development said Oregon Provincial Fr. Scott Santarosa, SJ, one of two Oregon Province delegates at GC 36. Director “His smile is warm and friendly, and he is always quick with a word of humor at meals or in the hallway. When I approached him to congratulate him, I said, ‘Felicidades, Padre General!’ Continued on pg. -

Living Tradition EN Edited 31.03.2020 Rev02

Secretariat for Secondary and Pre-secondary Education Society of Jesus Rome Jesuit Schools A Tradition in the 21st century ©Copyright Society of Jesus Secretariat for Education, General Curia, Roma Document for internal use only the right of reproduction of the contents is reserved May be used for purposes consistent with the support and improvement of Jesuit schools It may not be sold for prot by any person or institution Cover photos: Cristo Rey Jesuit College Prep School Of Houston Colégio Anchieta Colegio San Pedro Claver Jesuit Schools: A living tradition in the 21 century An ongoing Exercise of Discernment Author: ICAJE (e International Commission on the Apostolate on Jesuit Education) Rome, Italy, SEPTEMBER 2019, rst edition Version 2, March 2020 Contents 5 ................ Jesuit Schools: A Living Tradition to the whole Society 7 ................ Foreword, the conversation must continue... 10 .............. e current ICAJE Members 11 .............. INTRODUCTION 13 .............. • An Excercise in Discernment 15 .............. • Rooted in the Spiritual Excercises 17 .............. Structure of the Document 19 .............. PART 1: FOUNDATIONAL DOCUMENTS 20 .............. A) e Characteristics of Jesuit Education 1986 22 .............. B) Ignatian Pedagogy: A Practical Approach 24 .............. C) e Universal Apostolic Preferences of the Society of Jesus, 2019 28 .............. D) Other Important Documents 31 .............. PART 2: THE NEW REALITY OF THE WORLD 32 .............. 1) e Socio-Political Reality 40 .............. 2) Education 45 .............. 3) Changes in Religious Practice 47 .............. 4) Changes in the Catholic Church 49 .............. 5) Changes in the Society of Jesus 56 .............. PART 3: GLOBAL IDENTIFIERS OF JESUIT SCHOOLS 57 .............. To act as a universal body with a universal mission 59 .............. 1) Jesuit Schools are committed to being Catholic and to offer in-depth faith formation in dialogue with other religions and worldviews 62 ............. -

A Glossary of Terms Used in Ignatian and Jesuit Circles * Indicates a Term That Is Explained in Its Own Separate Entry in This Glossary

Do You Speak Ignatian? by George W. Traub, S.J. Zum Gedachtnis an "Onkel" Karl (Karl Rahner [1904-1984]) ©2002 by George W. Traub, S.J. All rights reserved For copies of this glossary in booklet form, contact: Carol Kelley Office of Mission & Ministry Xavier University 3800 Victory Parkway Cincinnati, OH 45207-2421 FAX: 513-745-2834 e-mail: [email protected] A Glossary of Terms Used in Ignatian and Jesuit Circles * Indicates a term that is explained in its own separate entry in this glossary. The term "God", which appears so often, is not asterisked. A.M.D.G.--Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam (Latin) - "For the greater glory of God." Motto of the Society of Jesus.* [See "magis."*] Apostle / apostolate / apostolic--Apostle is the role given to the inner circle of twelve whom Jesus "sent out" [on mission] and to a few others like St. Paul. Hence apostolate means a "mission endeavor or activity" and apostolic means "mission-like." Arrupe, Pedro (1907-1991)--As superior general of the Society of Jesus* for nearly 20 years, he was the central figure in the renewal of the Society after Vatican Council II,* paying attention both to the spirit of Ignatius* the founder and to the signs of our times. From the Basque country of northern Spain, he left medical school to join the Jesuits,* was expelled from Spain in 1932 with all the other Jesuits, studied theology in Holland, and received further training in spirituality and psychology in the U.S. Arrupe spent 27 years in Japan (where among many other things he cared for victims of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima) until his election in 1965 as superior general. -

General Congregation 35 N a Cold but Sunny January 7, 2008, Fr

Fr. General at Mass of Thanksgiving General Congregation 35 n a cold but sunny January 7, 2008, Fr. Thomas challenges facing the Society of Jesus. All congregations ORegan, SJ, provincial, Fr. Michael Boughton, SJ, and deal with two important concerns: What would best help Fr. Ronald Mercier, SJ, from the New England Province the Society serve God in the Church for the world? What of Jesuits participated in the Opening Mass for the 35th would preserve and advance Jesuit religious life? How is General Congregation of the Society of Jesus. God inviting us to discern the magis, God’s greater glory, today? Since the first official approval of the Order by 7 What is a General Congregation? Pope Paul III in 1540, there have been 26 Congregations A General Congregation, the highest governing body summoned to elect a General and 8 called only to review in the Society of Jesus, is summoned on the death of a and direct the work of the Society. General to elect his successor or when a General asks The 35th General Congregation was unique in that, to resign; in the latter case, with the Pope’s permission, for the first time in the history of the Society, a General the Congregation may accept the resignation and elect a Congregation was called by the Father General to elect his new General. At the same time it may address issues and successor. Key Events n January 19 • Delegates elected Fr. Adolfo Nicolás as the new Superior General Fr. Regan wrote: “On Saturday, in a very moving ceremony, the delegated elected a dynamic and saintly Jesuit, Fr. -

The Jesuits : Their Constitution and Teaching ; an Historical Sketch

" : ~~] I- Coforobm ZBrnbetsttp LIBRARY ESS && k&ttQaftj&m *& <\ szg/st This book is due two weeks from the last date stamped below, and if not returned or renewed at or before that time a fine of five cents a day will be incurred. THE JESUITS: THEIE CONSTITUTION AND TEACHING. %\\ pstorintl §>hk\, By W. C. CARTWRIGHT, M.P. LONDON: JOHN MUIUtAY, ALBEMARLE STKEET. 1876. The right oj Translation is reterved PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREKT AND CHARIKG CROSS. TO EAWDON BROWN, Tl his Volume is Inscribed, IN GRATEFUL RECOLLECTION OF MUCH KINDNESS RECEIVED, AND OF MANY PLEASANT HOURS ENJOYED IN CASA DELLA VIDA, BY THE AUTHOR. 65645 a2 PREFACE. This Volume is in substance a republication of two articles, that appeared in No. 274 and No. 275 of the ' Quarterly Eeview,' with some additions and corrections. The additions are in the first section, which treats of the Constitution of the Society of Jesus. They consist of historical matter calculated to illustrate more amply this branch of the subject. The corrections are in both sections —the most important one, however, being in the second, which relates to points of Doctrine. In reference to these corrections the Author would say a few words of general explanation. On appearance in the 'Quarterly Eeview,' the articles were fortunate enough to attract the attention of a well-known Koman Catholic periodical, the 'Month.' They were subjected to incisive criticisms in a series of papers in its pages, which have been ascribed to a competent master of the matter. These have been issued in a reprint, prefaced by observations, complaining that no notice had been taken by the present writer of the strictures passed on his state- ments, and charging him, on ground of this silence, with want of candour. -

![[B]Original Studio Albums[/B] 1981 - Face Value (Atlantic, 299 143) 01](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1319/b-original-studio-albums-b-1981-face-value-atlantic-299-143-01-2591319.webp)

[B]Original Studio Albums[/B] 1981 - Face Value (Atlantic, 299 143) 01

[b]Original Studio Albums[/b] 1981 - Face Value (Atlantic, 299 143) 01. In The Air Tonight 02. This Must Be Love 03. Behind The Lines 04. The Roof Is Leaking 05. Droned 06. Hand In Hand 07. I Missed Again 08. You Know What I Mean 09. Thunder And Lightning 10. I'm Not Moving 11. If Leaving Me Is Easy 12. Tomorrow Never Knows 1982 - Hello, I Must Be Going! (WEA, 299 263) 01. I Don't Care Anymore 02. I Cannot Believe It's True 03. Like China 04. Do You Know, Do You Care 05. You Can't Hurry Love 06. It Don't Matter To Me 07. Thru These Walls 08. Don't Let Him Steal Your Heart Away 09. The West Side 10. Why Can't It Wait 'til Morning 1985 - No Jacket Required (WEA, 251 699-2) 01. Sussudio 02. Only You Know & I Know 03. Long Long Way To Go 04. I Don't Wanna Know 05. One More Night 06. Don't Lose My Number 07. Who Said I Would 08. Doesn't Anybody Stay Together Anymore 09. Inside Out 10. Take Me Home 11. We Said Hello Goodbye 1989 - But Seriously (WEA, 2292-56984-2) 01. Hang In Long Enough 02. That's Just The Way It Is 03. Do You Remember 04. Something Happened On The Way To Heaven 05. Colours 06. I Wish It Would Rain Down 07. Another Day In Paradise 08. Heat On The Street 09. All Of My Life 10. Saturday Night And Sunday Morning 11.