Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis Commonly Complicates Treated Pulmonary Tuberculosis with Residual Cavitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is a Replacement Post for Current Incumbent, Mr. Mazhar Iqbal Who Has Secured a Post for Family Reasons Closer to His Home in North Wales

JOB DESCRIPTION CONSULTANT IN ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY WITH SPECIAL INTEREST IN ONCOLOGY & RECONSTRUCTION This is a replacement post for current incumbent, Mr. Mazhar Iqbal who has secured a post for family reasons closer to his home in North Wales. The post will become vacant from mid-October 2020. Currently the post is based at Wythenshawe hospitals with additional clinical sessions at Stepping Hill Hospital, Stockport and MDT and Clinic at the Christie Hospital, Manchester. Maxillofacial Surgery and Head and Neck Oncological services in Manchester are undergoing re-organization/transformation into a single operational site. The post holder will be expected to accommodate their sessions to fit into the new service. The employing Trust is Manchester Foundation Trust (MFT) Vision The vision of Manchester University Foundation Trust (formerly CMFT & UHSM) is to be recognised internationally as leading healthcare; excelling in quality, safety, patient experience, research, innovation, and teaching; dedicated to improving health and well-being for our diverse population. Our Values Open and Honest Dignity in Care Working Together Everyone Matters Profile Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT is a major teaching Trust with nine hospitals. The hospitals are Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI), Manchester Royal Eye Hospital (MREH), St Marys Hospital (SMH), and Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital (RMCH) all at the main Central Manchester site, the University Dental Hospital and Trafford General Hospital (TGH) and Wythenshawe Hospital, -

Annual Plan 2019/20

Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust Annual Plan 2019/20 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Key challenges and opportunities 3. Vision and Strategic Aims Priorities and Plans for 2019/20 4. Risk and Monitoring Arrangements 2 | P a g e 1. Introduction The purpose of developing an Annual Plan is to set out our plans for the coming year for: Delivering services to NHS performance standards - how we are going to deliver the activity required to meet demand and meet the required NHS performance targets, and Progressing our strategic aims – what progress we are going to make towards the achievement of our long vision and strategic aims and how we are going to achieve this. This document describes MFT and the context in which we are developing our plans; the challenges that we are facing and the opportunities open to us in both the coming year and in the longer-term. It sets out key plans for 2019/20 for both the group level teams and for each of the Hospitals and Managed Clinical Services, what they are aiming to achieve ultimately and what specifically will be achieved in 2019/20. It also describes how we manage the risks to delivery of the plan, and how we monitor delivery over the year. Who we are Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT) is one of the largest NHS trusts in England providing community, secondary, tertiary and quaternary services to the populations of Greater Manchester and beyond. We have a workforce of over 20,000 staff and are the main provider of hospital care to approximately 750,000 people in Manchester and Trafford and the single biggest provider of specialised services in the North West of England. -

A Report Looking Into the Public Perception of Trafford General Hospital

A report looking into the public perception of Trafford General Hospital May to June 2019 Published October 2019 Introduction to Healthwatch Trafford ............................................................... 2 Executive summary..................................................................................... 3 Key findings: .......................................................................................... 3 Questions and Recommendations .................................................................... 4 Background .............................................................................................. 6 Methodology ............................................................................................. 7 Data collection ....................................................................................... 7 Analysis of data ...................................................................................... 7 Points to note ........................................................................................... 8 Results ................................................................................................... 9 Q1. Which of the following services do you think Trafford General Hospital provides? ... 9 Q2. Trafford General Hospital has an Urgent Care Centre. Do you know what the difference is between this and an Accident and Emergency (A&E) department? ......... 11 Q3. Do you know what specialisms that Trafford General Hospital has? (That is, services that Trafford General Hospital are specialists -

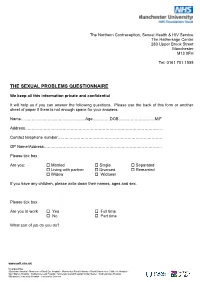

The Sexual Problems Questionnaire

The Northern Contraception, Sexual Health & HIV Service The Hathersage Centre 280 Upper Brook Street Manchester M13 0FH Tel: 0161 701 1555 THE SEXUAL PROBLEMS QUESTIONNAIRE We keep all this information private and confidential It will help us if you can answer the following questions. Please use the back of this form or another sheet of paper if there is not enough space for your answers. Name…………………………………………Age………….DOB………………………M/F Address………………………………………………………………………………………… Contact telephone number…………………………………………………………………… GP Name/Address……………………………………………………………………………. Please tick box Are you: Married Single Separated Living with partner Divorced Remarried Widow Widower If you have any children, please write down their names, ages and sex. Please tick box Are you in work Yes Full time No Part time What sort of job do you do? www.mft.nhs.uk Incorporating: Altrincham Hospital • Manchester Royal Eye Hospital • Manchester Royal Infirmary • Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital • Saint Mary’s Hospital • Trafford General Hospital • University Dental Hospital of Manchester • Wythenshawe Hospital • Withington Community Hospital • Community Services PAST HISTORY How would you describe the quality of your relationship within your family while growing up? Relationship with mother: Relationship with father: Relationship with brothers / sisters Do you remember any particular happy or unhappy times or events in your childhood / adolescence? Please say something about your past sexual experiences and relationships. www.mft.nhs.uk Incorporating: Altrincham Hospital • Manchester Royal Eye Hospital • Manchester Royal Infirmary • Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital • Saint Mary’s Hospital • Trafford General Hospital • University Dental Hospital of Manchester • Wythenshawe Hospital • Withington Community Hospital • Community Services GENERAL INFORMATION 1. Are you currently on any prescribed medication? YES/NO If yes please give details 2. -

Become a Member of Our NHS Foundation Trust

Become a Member of our NHS Foundation Trust We believe that good health services are vital to every local community and that our hospitals provide a modern, dependable, first-class healthcare service to the residents of Manchester, Trafford, Greater Manchester, and the North West that we can all be proud of. Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital Altrincham Hospital Manchester Royal Infirmary Wythenshawe Hospital University Dental Hospital of Manchester The Boulevard - Oxford Road Campus Manchester Royal Eye Hospital Saint Mary’s Hospital Withington Community Hospital Trafford General Hospital Benefits of being a Foundation Trust As a Foundation Trust we are directly accountable to our members, local population/communities, partners and other organisations with whom we work. As a Member of our Trust, you would have a very real opportunity, through your elected representatives (Governors), to shape our future and ensure services are developed that best meet your and your family’s needs. As a Trust with a large Children’s Hospital, we are conscious that young people need a way to articulate their views and we have developed our relationship with the Trust’s Youth Forum to ensure that young people are represented on our Council of Governors. Benefits of being a Foundation Trust Member Membership is completely free and is open to anyone who lives in England and Wales who is aged 11 years or over. Once a Member, you can choose how much you want to be involved. For example, you may just want to vote for representatives (Governors) during the election process and receive regular and exclusive membership information (newsletters and updates). -

Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis Is Associated with Adverse Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Veno-Venous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3241-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is associated with adverse clinical outcomes in critically ill patients receiving veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation I. Rodriguez-Goncer1 & S. Thomas2 & P. Foden3 & M. D. Richardson4,5 & A. Ashworth6 & J. Barker6 & C. G. Geraghty7 & E. G. Muldoon1,5,8 & T. W. Felton5,6,9 Received: 8 February 2018 /Accepted: 19 March 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract To identify the incidence, risk factors and impact on long-term survival of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) and Aspergillus colonisation in patients receiving vv-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). A retrospective eval- uation was performed of patients receiving vv-ECMO at a tertiary hospital in Manchester (UK) between January 2012 and December 2016. Data collected included epidemiological data, microbiological cultures, radiographic findings and outcomes. Cases were classified as proven IPA, putative IPA or Aspergillus colonisation according to a validated clinical algorithm. One hundred thirty-four patients were supported with vv-ECMO, median age of 45.5 years (range 16.4–73.4). Ten (7%) patients had putative IPA and nine (7%) had Aspergillus colonisation. Half of the patients with putative IPA lacked classical host risk factors for IPA. The median number of days on ECMO prior to Aspergillus isolation was 5 days. Immunosuppression and influenza A infection were significantly associated with developing IPA in a logistic regression model. Cox regression model demonstrates a three times greater hazard of death associated with IPA. Overall 6-month mortality rate was 38%. Patients with putative IPA and colonised patients had a 6-month mortality rate of 80 and 11%, respectively. -

Choosing Your Hospital

Choosing your hospital Manchester Primary Care Trust For most medical conditions, you can now choose where and when to have your treatment. This booklet explains more about choosing your hospital. You will also find information about the hospitals you can choose from. Second edition December 2006 Contents What is patient choice? 1 Making your choice 2 How to use this booklet 3 Where can I have my treatment? 4 Your hospitals A to Z 7 Your questions answered 26 How to book your appointment 28 What do the specialty names mean? 29 What does the healthcare jargon mean? 31 Where can I find more information and support? 33 How do your hospitals score? 34 Hospital score table 38 What is patient choice? If you and your GP decide that you need to see a specialist for more treatment, you can now choose where and when to have your treatment from a list of hospitals or clinics. Why has patient choice been introduced? Research has shown that patients want to be more involved in making decisions and choosing their healthcare. Most of the patients who are offered a choice of hospital consider the experience to be positive and valuable. The NHS is changing to give you more choice and flexibility in how you are treated. Your choices Your local choices are included in this booklet. If you do not want to receive your treatment at a local hospital, your GP will be able to tell you about your choices of other hospitals across England. As well as the hospitals listed in this booklet, your GP may be able to suggest community-based services, such as GPs with Special Interests or community clinics. -

Manchester Foundation Trust One Year Post Merger Report

One Year Post-Merger Report November 2018 Contents Foreword 3 Executive Summary 4 Key Messages 5 1 Introduction to Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust 6 2 The Creation of Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust 10 3 First Priorities Post-Merger 13 4 Establishment of Leadership and Organisational Structure 15 5 Establishing Robust Governance and Assurance Arrangements 21 6 Developing MFT’s Service Strategy 25 7 Planning for Major Clinical Transformation 27 8 Delivering Benefits in Year One Post-merger 29 9 Lessons Learned 40 10 Conclusion 46 One Year Post-Merger Report 2018 2 Foreword Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT) organisational structure that is fit for purpose. This was launched on 1st October 2017. The new means we can press on to finalise the service strategy organisation brought together a group of nine which will support more fundamental transformation hospitals plus community services, providing a once over the coming years. This is exciting work which in a lifetime opportunity to deliver even better services will continue to involve staff from across our nine for the people of Manchester, Trafford and beyond. hospitals and community services, along with partner organisations. Our first priority was to keep services running safely and smoothly. On day one, patients saw little change All this work has taken place against a challenging apart from the new name and new lanyards for backdrop. Like other NHS Trusts, we face increasing staff. We wanted to minimise disruption to maintain demand on our services, workforce challenges and stability for staff and ensure patient safety. financial pressures. Despite this headwind our staff have continued to deliver outstanding care whilst We quickly started detailed planning to maximise the also developing single services and delivering early opportunities to improve services for patients and transformation. -

MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY NHS FOUNDATION TRUST MEMBERSHIP – Faqs

MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY NHS FOUNDATION TRUST MEMBERSHIP – FAQs WHAT IS AN NHS FOUNDATION TRUST? NHS Foundation Trusts (FT) are based upon the mutual organisation model and represent a profound change in the history of the NHS and the way in which hospital services are managed and provided. They form part of the Government’s plan to create a patient-centred National Health Service via the provision of high quality care which is shaped by the needs and wishes of patients/public. WHY DO NHS FOUNDATION TRUSTS HAVE A MEMBERSHIP? All NHS Foundation Trusts (FT) have a duty to engage with their local communities and encourage local people to become members of the organisation (ensuring that membership is representative of the communities that they serve). By this method, FTs provide greater accountability to patients, service users, local people and NHS staff with the overriding principle being that that members have a sense of ownership over the services that the FT provides. Members are able to influence the Trust’s decision-making processes and forward plans. By directly involving our members in this way means that we are able to respond, much more quickly and effectively, to the identified needs of our patients and their families and ultimately achieve and deliver a patient-centred National Health Service, via the provision of high quality care, which is shaped by the needs and wishes of patients/public and staff. WHO CAN BECOME A MEMBER? Those living in the communities, that we serve, can become public members with MFT’s membership community being made up of both Public Members (including local residents, patients and carers) and Staff Members (including MFT’s employees and other people who provide services to the Trust). -

Annual Report and Accounts 1St April 2018 to 31St March 2019

Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust Annual Report and Accounts 1st April 2018 to 31st March 2019 1 2 Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust Annual Report and Summary Accounts - 1st April 2018 to 31st March 2019 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Schedule 7, paragraph 25 (4) (a) of the National Health Service Act 2006. 3 © 2018 Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust 4 Contents Page 1 Welcome from our Group Chairman and Group Chief Executive 6 1.1 Highlights of 2018/19 8 1.2 Service developments 15 1.3 Improving patient and staff experience 15 1.4 Research and Innovation 16 1.5 Our Charity 19 2 Performance Report 2.1 Overview of performance 21 2.2 Performance analysis 34 3 Accountability Report 3.1 Directors’ Report 44 3.2 Remuneration Report 54 3.3 Staff Report 84 3.4 NHS Foundation Trust Code of Governance disclosures 96 3.5 Regulatory ratings 101 3.6 Statement of Accounting Officer’s responsibilities 102 3.7 Annual Governance Statement 104 4 Quality Report 118 5 Auditors’ Reports 272 6 Foreword to the Accounts 278 7 Annual Accounts 279 Note: Throughout this report where comparisons are made with 2017/18 data, these are for the six months from 1st October 2017 (when MFT was formed) to 31st March 2018. 5 1. Welcome and highlights of 2018/19 Welcome from our Chairman and Chief Executive We are very proud to introduce this report for 2018/19, and to share with you the achievements of our first full year in operation. Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT) was launched on 1st October 2017 bringing together nine hospitals plus community services and providing a once in a lifetime opportunity to deliver even better services for the people of Manchester, Trafford and beyond. -

A Consultation on Plans to Redesign Hospital Services in Trafford

A new health DEAL High Quality Safe Accessible Sustainable for Trafford A consultation on plans to redesign hospital services in Trafford Full document Other versions of this document and requests for support This document is available in other languages and formats. This document is also available in large print, audio and Braille versions, at request, by contacting the communications and engagement team at NHS Trafford. Postal address: Email: 2nd Floor [email protected] Oakland House Telephone: Talbot Road 0161 873 9527 Manchester Text relay: M16 0PQ 18001 0161 873 9527 Contents 03 Contents page 04 Foreword page 06 Our vision for a new health deal for Trafford page 10 How things are now page 18 Why change is needed page 23 Involving people page 25 Hospital service redesign options page 29 The proposal page 32 How patients will be affected page 39 Where services would be accessed under the new proposal page 41 Further work page 42 Implementation page 42 How to have your say page 43 How to get in touch or find out more page 44 What happens next? page 45 Supporting documentation A new health DEAL for Trafford A consultation on plans to redesign hospital services in Trafford 04 A new health DEAL for Trafford A consultation on plans to redesign hospital services in Trafford Foreword Whoever you are, or wherever you’re from, there is always somewhere you can go to get looked after by the NHS. We are committed to making sure that this remains the case in Trafford. But to make sure that future generations get the NHS Trafford General Hospital is one of the smallest hospitals they expect and deserve, at a cost that’s affordable and in the country. -

Menopause Clinic Secretary the Northern Contraception, Sexual Health and HIV Service the Hathersage Centre 280 Upper Brook Street Manchester M13 0FH

The Menopause Clinic Secretary The Northern Contraception, Sexual Health and HIV Service The Hathersage Centre 280 Upper Brook Street Manchester M13 0FH Tel: 0161 701 1555 Menopause Clinic Please complete and return to the address above Once reviewed we will contact you for an appointment in the menopause clinic Date you first made contact with us ____________________ Name: Miss/Mrs/Ms _____________________________________________________________ Address: ___________________________________________________ ________________ Date of Birth ______________________________________ Telephone number: ______________ Name of GP: ______________________________________________________________ When was your last menstrual period? ____________________________________________ Have you had a hysterectomy? Yes/No If yes, when? _________________________________ Why did you have to have the hysterectomy? _______________________________________ When was your last smear? ___________________________________________________ Have you had any other gynaecological problems? (Please give details) _________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________ How many children have you had? _____ Any miscarriages or terminations? ______________ List any serious illnesses you have had with dates: ________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________ List any operations you have had with dates: _____________________________________________