1990 Acharya Ramamurti Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Likewise, No One Can Destroy a Person, but It's Own Mindset Can!

Important Points No one can destroy iron, but it’s own rust can! Likewise, no one can destroy a person, but it’s own mindset can! ImportantQuestion Points 1 / प्रश्न 1 भारतीय डाक विभाग ने ककस गैर-लाभकारी संगठन के सान में डाक किकि जारी ककया है? The Indian Postal services honoured which non-profit organization by launching their postal stamps? 1. भारतीय योग संान / Bhartiya Yog Sansthan 2. जगन्नाथ सेिा संान / Jagannath Seva Sansthan 3. नारायण सेिा संान / Narayan Seva Sansthan 4. महािीर कैंसर संान / Mahavir Cancer Sansthan ImportantAnswer Points नारायण सेिा संान / Narayan Seva Sansthan • Kailash Agarwal, founder and chairman of Narayan Seva Sansthan • The stamp of Rs 5 • Narayan Seva Sansthan, the Udaipur-based non-profit organisation ImportantQuestion Points 2 / प्रश्न 2 ककस देश ने ‘14िें हॉस्पििललिी इंकडया एंड एक्सप्लोर द िर्ल्ड िाकषडक इंिरनेशनल िरैिल अिाडडडस-2018’ में पयडिन पुरस्कारता जी है? Which country won tourism award at the 14th Hospitality India and Explore the World Annual International travel Awards 2018? 1. श्रीलंका / Sri Lanka 2. फ्रांस / France 3. भारत / India 4. नेपाल / Nepal ImportantAnswer Points नेपाल / Nepal • 14th Edition - Hospitality India and Explore the World Annual International Travel Awards 2018 • Held in New Delhi. • Nepal's Chandragiri Hills Limited was conferred as Nepal's best tourism destination • Deepak Raj Joshi, the CEO of Nepal Tourism Board • Guest of honour- K.J. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

The Cultural Dimension of Education

THE CULTURAL DIMENSION OF EDUCATION www.ignca.gov.in THE CULTURAL DIMENSION OF EDUCATION Edited by BAIDYANATH SARASWATI 1998 xxii+258pp. col. illus., ISBN: 81-246-0101-1, Rs 700(HB) CONTENTS How can a sensibly worked-out system of education afford a Foreword (Kapila Vatsyayan) symbiosis between modernity Prologue (Chitra Naik) and wisdom tradition Addressing the vital question, the authors Introduction (Baidyanath Saraswati) here look afresh at the relevance of art in the age of 1. Gandhian Experiment of Primary Education:The Story of science/technocentrism, the role Taman Kanak-Kanak 'Gandhi' (Gedong Bagoes Oka) of education in promoting peace 2. Poverty and Education: The Samanwaya Ashram (Dwarko and concord, Gandhian system Sundrani) of basic education& and, finally, 3. Rural Context of Primary Education: Searching for the how far Indias national concerns Roots (Shakuntala Bapat & Suman Karandikar) are reflected in its national policy 4. The Bose Foundation School (Baidyanath on education. Saraswati, Shivashankar Dube& Ram Lakhan Maurya) 5. Ghadatar: An Enquiry into the Invisible Order (Haku Shah) As assemblage of 16 education- 6. My Experiments with Education (D. Patnaik) related essays, this volume is the outcome of a Conference on the Art as a Tool for Cultural Rejuvenation (Dinanath Pathy) 7. "Cultural Dimension of Education 8. Photography in Education (Ravi Chopra) and Ecology", held in New Delhi 9. Education for Value-Creation and Leadership: A Case Study of on 13-16 October 1995 as a part the Rangaprabhat Centre (N. Radhakrishnan) of the Unesco Chair activities (in 10. Education Through Art (Nita Mathur) the field of cultural development) 11. -

Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ANNUAL Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 © Gandhi and People Gathering by Shri Upendra Maharathi Mahatma Gandhi by Shri K.V. Vaidyanath (Courtesy: http://ngmaindia.gov.in/virtual-tour-of-bapu.asp) (Courtesy: http://ngmaindia.gov.in/virtual-tour-of-bapu.asp) ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti ANNUAL REPORT - 2019-2020 Contents 1. Foreword ...................................................................................................................... 03 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 05 3. Structure of the Samiti.................................................................................................. 13 4. Time Line of Programmes............................................................................................. 14 5. Tributes to Mahatma Gandhi......................................................................................... 31 6. Significant Initiatives as part of Gandhi:150.................................................................. 36 7. International Programmes............................................................................................ 50 8. Cultural Exchange Programmes with Embassies as part of Gandhi:150......................... 60 9. Special Programmes..................................................................................................... 67 10. Programmes for Children............................................................................................. -

Olitical Amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of olitical amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA fc I A Guide to the Microfiche Collection POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Associate Editor and Guide compiled by August A. Imholtz, Jr. A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicaîion Data: Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by a printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-55655-206-8 (microfiche) 1. Political parties-India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1I527 1989<MicRR> 324.254~dc20 89-70560 CIP International Standard Book Number: 1-55655-206-8 UPA An Imprint of Congressional Information Service 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD20814 © 1989 by University Publications of America Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. TABLE ©F COMTEmn Introduction v Note from the Publisher ix Reference Bibliography Part 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups India Congress Committee. (Including All India Congress Committee): 1-282 ... 1 Communist Party of India: 283-465 17 Communist Party of India, (Marxist), and Other Communist Parties: 466-530 ... 27 Praja Socialist Party: 531-593 31 Other Socialist Parties: -

Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State City PIN Details Amount Transfer to IEPF DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O

Biocon Limited Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend for the FY 2007-08 Folio NO/Demat Due date for Name Middle Name Last Name Address Country State City PIN details Amount transfer to IEPF DILIP P SHAH IDBI BANK, C.O. G.SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO022473 250.00 22-AUG-2015 CAP MARK SERV PLOT 82/83 ROAD 7 STREET NO 15 MIDC, ANDHERI.EAST, MUMBAI SURAKA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAMANYAM HEAD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043568 250.00 22-AUG-2015 CAPITAL MKT SER C P U PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 ST NO 15 OPP RAMBAXY LAB ANDHERI MUMBAI (E) RAMANUJ MISHRA IDBI BANK LTD C/O G SUBRAHMANYAM INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO047663 250.00 22-AUG-2015 HEAD CAP MARK SERV CPU PL 82/83 RD 7 ST 15 OPP SPECAILITY RANBAXY LAB MIDC ANDHERI EAST MUMBAI URMILA LAXMAN SAWANT C/O KOTAK MAHINDRA BANK LTD VINAYA INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400098 BIO043838 250.00 22-AUG-2015 BHAVYA COMPLEX 5TH FLR 159-A CST ROAD KALINA SANTACRUZ E MUMBAI PHONE- 56768300 NEHA KAMLESH SHAH G SUBRAHMANYAM HEAD CAPITAL MARKET INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400093 BIO043408 250.00 22-AUG-2015 SERVISES CENTRAL PROCESSING UNIT PLOT NO 82/83 ROAD NO 7 STREET NO 5 MIDC ANDHERI (E) MUMBAI NO NA INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI BIO054733 250.00 22-AUG-2015 NO NA INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI BIO054734 250.00 22-AUG-2015 NO NA INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI BIO054748 250.00 22-AUG-2015 NO 305 GOLF MANOR WIND TUNNEL ROAD 22-AUG-2015 MANISH SALNI MURUGESHPALYA BANGALORE INDIA KARNATAKA BANGALORE 560017 BIO038066 250.00 G 16 Marina Arcade Connaught Circus New Madhubani Investments P Ltd Delhi INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110001 IN30177410005267 4250.00 22-AUG-2015 VANDANA GOGIA HOUSE NO.904 SECTOR-28 FARIDABAD INDIA HARYANA FARIDABAD 121002 IN30209210046456 2500.00 22-AUG-2015 C/O JITENDRA PRATAP SINGH RESIDENT ENGINEER TEMPORARY DEPART. -

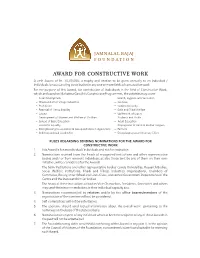

Constructive Work a Cash Award of Rs

jamnalal bajaj f o u n d a t i o n award for constructive work A cash Award of Rs. 10,00,000, a trophy and citation to be given annually to an individual / individuals for outstanding contribution in any one or more fields of constructive work. For the purpose of this Award, for contribution of individuals in the field of Constructive Work, which are based on Mahatma Gandhi’s Constructive Programmes, the activities may cover : - Rural Development - Health, Hygiene and Sanitation - Khadi and other Village Industries - Go-Seva - Prohibition - Communal Unity - Removal of Untouchability - Dalit and Tribal Welfare - Labour - Upliftment of Lepers - Development of Women and Welfare of Children - Students and Youth - Spread of Basic Education - Adult Education - Economic Equality - Propagation of Hindi & mother tongues - Strengthening Co-operative & Group Activities in Agriculture - Farmers - Building up Local Leadership - Encouraging Local Voluntary Effort RULES REGARDING SENDING NOMINATIONS FOR THE AWARD FOR CONSTRUCTIVE WORK 1. This Award is for an individual / individuals and not for institution. 2. Nominations received from the heads of recognized institutions and other representative bodies and / or from eminent individuals as also those sent by any of them on their own initiative, will be considered for the Awards. The term 'Institutions and other representative bodies' covers Universities, Research Bodies, Social Welfare Institutions, Khadi and Village Industries Organisations, Chambers of Commerce, Rotary, Inner Wheel and Lions Clubs, concerned Government Departments of the Centre and the States and similar bodies. The heads of these institutions or bodies-Vice-Chancellors, Presidents, Secretaries and others may send their recommendations in their individual capacity also. -

List of Shareholders Whose Shares Are Transferred to IEPF- 2009-10

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the shares transferred to Investor Education and Protection Fund. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-4. CIN L24121MH1979PLC021360 Prefill Company Name DEEPAK FERTILISERS AND PETROCHEMICALS CORPORATION LTD Nominal value of shares 4734900.00 Validate Clear Actual Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Nominal value of Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Number of shares transfer to IEPF (DD- Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number shares MON-YYYY) ARCHANA RAIZADA PREM SINGH RAIZADA STUDENT C/O MRS LATA RAIZADA D-28 74 BINDIA MADHYA PRADESH BHOPAL 462003 P175722 50 500.00 31-OCT-2017 D ANBALAGAN NA 39/F RAILWAY COLONY KODAMBAINDIA TAMIL NADU CHENNAI 600024 P188862 50 500.00 31-OCT-2017 MOHAMMED ALIM MOHAMMED SALIM SALES EXECUTIV C/O GODREJ 31 JANPATH BAPUJI NINDIA ORISSA BHUBANESHWAR 751009 P280406 75 750.00 31-OCT-2017 DIPTI SHAH PRANAYKUMAR SHAH HOUSE HOLD NARAYAN GULBAI TEKRA CHINUBHINDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380006 P124762 50 500.00 31-OCT-2017 GURMUKH SINGH SIDHU KISHAN SINGH 103 R MODEL TOWN LUDHIANA INDIA PUNJAB LUDHIANA 141002 IN301143-IN301143-10 75 750.00 31-OCT-2017 DOUGLAS C LAMOND ROBERT M LAMOND BUSINESS 19/2/A MANISH DEEP CO OP SOCIEINDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400058 P223346 150 1500.00 31-OCT-2017 KISHORE NARBHERAM BAVISHI NARBHERAM N BAVISHI SERVICE 8-JANJIRA HOUSE RAJAWADI ROAINDIA -

1. Telegram to the Aga Khan 2. Letter to Jivanji D. Desai

1. TELEGRAM TO THE AGA KHAN SODEPUR, December 7, 1945 H. H. AGAKHAN BOMBAY MANY THANKS YOUR WIRE. WOULD LOVE TO MEET YOU AND LEARN FROM YOU WAY TO SOLUTION COMMUNAL PROBLEM. MAULANA IS ILL BUT AT WORK. EXPECTING TO REACH WARDHA FEBRUARY. WRITING. GANDHI From a copy: Pyarelal Papers. Courtesy: Pyarelal 2. LETTER TO JIVANJI D. DESAI SODEPUR, December 7, 1945 CHI. JIVANJI, I got your proof-copy of the pamphlet on constructive work yesterday. I wanted to use that copy here and did so. But I had already gone through the proof earlier. As there is no letter accom- panying it, I don’t quite understand why you have sent it. You have given a heading to my preface but there is no heading on the page on which the pamphlet itself begins. I infer from this that final touches still remain to be given to the printing. I have of course asked Pyare- lalji to write to you about this, but I think it is better to dictate this just now in the morning. I have the impression that I have already written to you about the cover. My suggestion is that the eighteen headings which you have given in the pamphlet should be reproduced on the cover in their proper order, with the page number given against each. This will help the reader and we shall be able to show what topics have been covered. The topics can also be shown on the cover in the form of a circle. We can have a drawing of the spinning-wheel in the centre and the head- ings can be printed round it like the planets round the sun. -

Table of Contents GA POWER CAPSULE | NIACL AO MAINS 2019

GA POWER CAPSULE | NIACL AO MAINS 2019 Table of Contents GA POWER CAPSULE | NIACL AO MAINS 2019 ..................................................................................................... 3 Interim Budget 2019 Highlights ................................................................................................................................. 3 Highlights of Rural Outreach ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Must DO Current Affairs for the NIACL AO Mains 2019 ........................................................................................ 5 Padma Awards 2019 Announced: Complete List of Winners ....................................................................... 6 Australian Open 2019 Concludes: Complete List of Winners ....................................................................... 8 Indonesia Masters Title 2019: Complete List of Winners .............................................................................. 8 International Cricket Council (ICC) Awards 2018 ............................................................................................. 9 Golden Globe Awards 2019 Announced: List of Important Winners......................................................... 9 15th Pravasi Bharatiya Diwas: All You Need To Know. ................................................................................. 9 PM Modi 3-Day Visit to Gujarat: Complete Highlights .................................................................................10 -

June 2012 July 2012

June 2012 • Aung San Suu Kyi has finally received her honourary degree from Oxford University. The leader of Myanmar's opposition is being honoured on 20 june at the university's Encaenia ceremony, in which it presents honourary degrees to distinguished people.Suu Kyi, who is making her first visits outside of her native country in 24 years, was awarded the honourary doctorate in civil law in 1993 but was unable to collect it under house arrest in Myanmar.She studied philosophy, politics and economics at St. Hugh's College in Oxford between 1964 and 1967. • Bulu Imam of Jharkhand and Binayak Sen of Chhattisgarh has been invited to receive the Gandhi Foundation International Peace award 2011 at a function to be organized at the House of Lords in the UK on June 12.While individual letter of invitation has been sent to both of them, the citation released by the Gandhi Foundation on its website reads that the duo have been selected for the international peace award for their humanitarian work and their practice of non-violence. The Foundation honours individuals or groups annually based on their work in the field of promoting or practising Gandhian philosophy. Hazaribag-based Bulu Imam has been selected for the award in the wake of his non- violent approach in protesting coal mining and environmental damage to Upper Damodar Valley (Karnapura) because of open cast coal mines. • Israeli scientist Daniel Hillel won the World Food Prize 2012 on 13 June 2012. The work and motivation of Daniel Hillel built the bridge between the divisions and to promote peace and understanding in the Middle East by advancing a breakthrough achievement. -

1. Letter to J. C. Kumarappa 2. Letter to Amrit Kaur

1. LETTER TO J. C. KUMARAPPA SEVAGRAM, WARDHA, August 18, 1941 MY DEAR KUMARAPPA, I have hurriedly gone through your draft. It reads all right. You may circulate it. But I shall study it carefully before you meet. BAPU From a photostat: G.N. 10157 2. LETTER TO AMRIT KAUR August 18, 1941 MY DEAR IDIOT, This thing about the post is vexing. But what is one to do with a village P[ost] O[ffice]? The second vexing thing is your indifferent condition. Why should you not feel first class? Could it have anything to do with your having taxed yourself too much over Jamnalal? He is in rapturesover the kindness shown to him by you all— meaning you and your. .1 The thought has just occurred to me and I have passed it on to you. Anyway it is time you got well. We had a glorious day here. We had prayers at which Gurudev’s songs were sung, the morning “Jivana jakhan2” by Sushila and the “ Anand lok[e]3” in the evening by Prabhakar who is proving a fine singer. We had a pice collection from every adult and more from those who could pay more. The Ashramites not having any money of their own spun for one hour and got one pice for their labour at market price. Maganlal gave Rs. 2,500, Janakibehn Rs. 110, Sushila Rs. 500 in 10 instalments, i.e., Rs. 50 out of her salary. Therefore, we have a goodly sum in Sevagram. Ashadevi went out for collection and prayer in Wardha.