What Is the Future of Indian Philosophy? ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39987948 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Abhinavagupta’s Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir A dissertation presented by Benjamin Luke Williams to The Department of South Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of South Asian Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2017 © 2017 Benjamin Luke Williams All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Parimal G. Patil Benjamin Luke Williams ABHINAVAGUPTA’S PORTRAIT OF GURU: REVELATION AND RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN KASHMIR ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to recover a model of religious authority that placed great importance upon individual gurus who were seen to be indispensable to the process of revelation. This person-centered style of religious authority is implicit in the teachings and identity of the scriptural sources of the Kulam!rga, a complex of traditions that developed out of more esoteric branches of tantric "aivism. For convenience sake, we name this model of religious authority a “Kaula idiom.” The Kaula idiom is contrasted with a highly influential notion of revelation as eternal and authorless, advanced by orthodox interpreters of the Veda, and other Indian traditions that invested the words of sages and seers with great authority. -

Annual Report 2016-17

Jeee|<ekeâ efjheesš& Annual Report 201201666---20120120177 केb6ीय ितबती अaययन िव िवcालय Central University of Tibetan Studies (Deemed University) Sarnath, Varanasi - 221007 www.cuts.ac.in Conference on Buddhist Pramana A Glance of Cultural Programme Contents Chapters Page Nos. 1. A Brief Profile of the University 3 2. Faculties and Academic Departments 9 3. Research Departments 45 4. Shantarakshita Library 64 5. Administration 79 6. Activities 89 Appendices 1. List of Convocations held and Honoris Causa Degrees Conferred on Eminent Persons by CUTS 103 2. List of Members of the CUTS Society 105 3. List of Members of the Board of Governors 107 4. List of Members of the Academic Council 109 5. List of Members of the Finance Committee 112 6. List of Members of the Planning and Monitoring Board 113 7. List of Members of the Publication Committee 114 Editorial Committee Chairman: Dr. Dharma Dutt Chaturvedi Associate Professor, Dean, Faculty of Shabdavidya, Department of Sanskrit, Department of Classical and Modern Languages Members: Shri R. K. Mishra Documentation Officer Shantarakshita Library Shri Tenzin Kunsel P. R. O. V.C. Office Member Secretary: Shri M.L. Singh Sr. Clerk (Admn. Section-I) [2] A BRIEF PROFILE OF THE UNIVERSITY 1. A BRIEF PROFILE OF THE UNIVERSITY The Central University of Tibetan Studies (CUTS) at Sarnath is one of its kind in the country. The University was established in 1967. The idea of the University was mooted in course of a dialogue between Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India and His Holiness the Dalai Lama with a view to educating the young Tibetan in exile and those from the Himalayan regions of India, who have religion, culture and language in common with Tibet. -

Philosophy in Classical India the Proper Work of Reason

Philosophy in Classical India The proper work of reason Jonardon Ganeri London and New York 2Rationality, emptiness and the objective view 2.1 THOUGHT AND REALITY Is reality accessible to thought? Could it not be that there are limits on our cognitive capacities, and the way the world is, whatever that might be, is something beyond our powers of understanding? What there is in the world might extend beyond what we, in virtue of our natural cognitive endowment, have the capacity to form a conception of. The thesis is a radical form of scepticism. It is a scepticism about what we can conceive rather than about what we can know. Nagarjuna (c. AD 150), founder of the Madhyamaka school of Indian Buddhism, is a radical sceptic of this sort. Indeed, he is still more radical. His thesis is not merely that there may be aspects of reality beyond the reach of conception, but that thought entirely fails to reach reality. If there is a world, it is a world about which we can form no adequate conception. Moreover, since language expresses thought, it is a world about which we cannot speak. Where the reach of thought turns back, language turns back. The nature of things (dharmata) is, like nirvana, without origin and without decay. (MK 18.7) Not dependent on another, calm, not conceptualised by conception, not mentally constructed, not diverse – this is the mark of reality (tattva). (MK 18.9) This indeed is for Nagarjuna the true meaning of the Buddha’s teachings, a meaning so disruptive to common reason that the Buddha was reluctant to spell it out. -

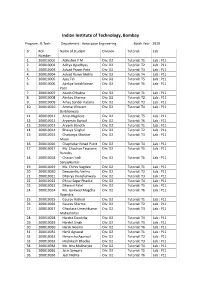

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

A Love Knowing Nothing: Zen Meets Kierkegaard

Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/ Volume 22, 2015 A Love Knowing Nothing: Zen Meets Kierkegaard Mary Jeanne Larrabee DePaul University Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All en- quiries to: [email protected]. A Love Knowing Nothing: Zen Meets Kierkegaard Mary Jeanne Larrabee 1 Abstract I present a case for a love that has a wisdom knowing nothing. How this nothing functions underlies what Kier- kegaard urges in Works of Love and how Zen compassion moves us to action. In each there is an ethical call to love in action. I investigate how Kierkegaard’s “religiousness B” is a “second immediacy” in relation to God, one spring- ing from a nothing between human and God. This imme- diacy clarifies what Kierkegaard takes to be the Christian call to love. I draw a parallel between Kierkegaard’s im- mediacy and the expression of immediacy within a Zen- influenced life, particularly the way in which it calls the Zen practitioner to act toward the specific needs of the person standing before one. In my understanding of both Kierkegaard and Zen life, there is also an ethics of re- sponse to the circumstances that put the person in need, such as entrenched poverty or other injustices. 1 Department of Philosophy, DePaul University. Email: [email protected]. -

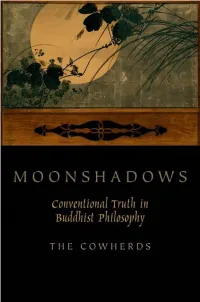

Moonshadows: Conventional Truth in Buddhist Philosophy

Moonshadows This page intentionally left blank Moonshadows Conventional Truth in Buddhist Philosophy T HE C OWHERDS 2011 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2011 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cowherds (Authors) Moonshadows : conventional truth in Buddhist philosophy / the Cowherds. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-975142-6; ISBN 978-0-19-975143-3 (pbk.) 1. Truth—Religious aspects—Buddhism. 2. Buddhist philosophy. I. Title. BQ4255.C69 2011 121.088′2943—dc22 2009050158 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Preface This is an unusual volume. It is neither an anthology nor a monograph. We prefer to think of it as a polygraph— a collectively written volume refl ecting the varying views of a large collection of authors. -

Indian Philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article

Indian philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article Indian philosophy the systems of thought and reflection that were developed by the civilizations of the Indian subcontinent. They include both orthodox (astika) systems, namely, the Nyaya, Vaisesika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva-mimamsa, and Vedanta schools of philosophy, and unorthodox (nastika) systems, such as Buddhism and Jainism. Indian thought has been concerned with various philosophical problems, significant among them the nature of the world (cosmology), the nature of reality (metaphysics), logic, the nature of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and religion. General considerations Significance of Indian philosophies in the history of philosophy In relation to Western philosophical thought, Indian philosophy offers both surprising points of affinity and illuminating differences. The differences highlight certain fundamentally new questions that the Indian philosophers asked. The similarities reveal that, even when philosophers in India and the West were grappling with the same problems and sometimes even suggesting similar theories, Indian thinkers were advancing novel formulations and argumentations. Problems that the Indian philosophers raised for consideration, but that their Western counterparts never did, include such matters as the origin (utpatti) and apprehension (jñapti) of truth (pramanya). Problems that the Indian philosophers for the most part ignored but that helped shape Western philosophy include the question of whether knowledge arises from experience or from reason and distinctions such as that between analytic and synthetic judgments or between contingent and necessary truths. Indian thought, therefore, provides the historian of Western philosophy with a point of view that may supplement that gained from Western thought. A study of Indian thought, then, reveals certain inadequacies of Western philosophical thought and makes clear that some concepts and distinctions may not be as inevitable as they may otherwise seem. -

In Jain Philosophy

Philosophy Study, April 2016, Vol. 6, No. 4, 219-229 doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2016.04.005 D DAVID PUBLISHING Matter (Pudgalastikaya or Pudgala) in Jain Philosophy Narayan Lal Kachhara Deemed University Pudgalastikaya is one of the six constituent dravyas of loka in Jainism and is the only substance that is sense perceptible. The sense attributes of pudgala are colour, taste, smell, and touch properties which become the basis of its diversity of forms and structures. The smallest constituent of pudgala is paramanu; the other forms are its combinations. The combination of parmanus forms various states of the matter. The paper describes different types of combinations and modes, rules for combinations and properties of aggregates known as vargana. Some varganas associate with the soul and form various types of bodies of organisms and others exist as forms of matter in loka (universe). The paramanu defines the smallest units of energy, space, time, and sense quality of pudgala. Pudgala exists in visible and invisible forms but anything that is visible is definitely pudgala. Pudgala is classified in various ways; one of them is on the basis of touch property and there are pudgalas having two touches, four touches, and eight touches, each class having some specific character that differentiates them in respect of stability and motion. Pudgala is also classified as living, prayoga-parinat, and non-living, visrasa-parinat. The living matter existing as bodies of organisms exhibits some properties that are not found in non-living matter. Modern science has no such distinction which has become a cause of confusion in recognizing the existence of soul. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

Jain Philosophy and Practice I 1

PANCHA PARAMESTHI Chapter 01 - Pancha Paramesthi Namo Arihantänam: I bow down to Arihanta, Namo Siddhänam: I bow down to Siddha, Namo Äyariyänam: I bow down to Ächärya, Namo Uvajjhäyänam: I bow down to Upädhyäy, Namo Loe Savva-Sähunam: I bow down to Sädhu and Sädhvi. Eso Pancha Namokkäro: These five fold reverence (bowings downs), Savva-Pävappanäsano: Destroy all the sins, Manglänancha Savvesim: Amongst all that is auspicious, Padhamam Havai Mangalam: This Navakär Mantra is the foremost. The Navakär Mantra is the most important mantra in Jainism and can be recited at any time. While reciting the Navakär Mantra, we bow down to Arihanta (souls who have reached the state of non-attachment towards worldly matters), Siddhas (liberated souls), Ächäryas (heads of Sädhus and Sädhvis), Upädhyäys (those who teach scriptures and Jain principles to the followers), and all (Sädhus and Sädhvis (monks and nuns, who have voluntarily given up social, economical and family relationships). Together, they are called Pancha Paramesthi (The five supreme spiritual people). In this Mantra we worship their virtues rather than worshipping any one particular entity; therefore, the Mantra is not named after Lord Mahävir, Lord Pärshva- Näth or Ädi-Näth, etc. When we recite Navakär Mantra, it also reminds us that, we need to be like them. This mantra is also called Namaskär or Namokär Mantra because in this Mantra we offer Namaskär (bowing down) to these five supreme group beings. Recitation of the Navakär Mantra creates positive vibrations around us, and repels negative ones. The Navakär Mantra contains the foremost message of Jainism. The message is very clear. -

Some Questions Concerning the Ugc Course in Astrology

SOME QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE UGC COURSE IN ASTROLOGY Kushal Siddhanta 18 AUGUST 2001. Dr. Murali Manohar cient Indian astronomer Varahamihira who Joshi, the present Union HRD Minister and in the sixth century AD spoke about the a former professor of physics in the Alla- earth's rotation.” Citing another fact in sup- habad University, was invited to the IIT, port of introducing astrology as a university Kharagpur, as the chief guest at an open- course, he said, 16 universities of the coun- ing function organized on the occasion of try had already been offering astrology as its fiftieth foundation anniversary. The a subject in various forms. So his govern- West Bengal Chief Minister Mr. Buddhadeb ment is doing nothing new. People should Bhattacharya was another guest. not oppose the astrology and other courses only on political reasons. There may be de- As expected, Mr. Bhattacharya in his bates and arguments over the issue. The speech indirectly criticized the policy of the Government, he assured all, was ready to Union Government to introduce worn out hear. So on and so forth. subjects like astrology, paurohitya, vas- tushastra, yoga and human consciousness, It all had started when the UGC issued a etc., in the universities through the Univer- circular on 23 February 2001 with a pro- sity Grant Commission (UGC). Dr. Joshi posal to all the universities of the country in his address, however, did not go into to introduce UG and PG courses as well the trouble of explaining why his depart- as doctoral researches in Vedic Astrology ment was so keen on funding these anti- which it later renamed in parenthesis as quated subjects in the universities in spite Jyotirvigyan (astronomy). -

Ateísmo, Panteísmo, Acosmismo Y Monoteísmo En La Filosofía De Hegel | Javier Fabo Lanuza

Ateísmo, panteísmo, acosmismo y monoteísmo en la filosofía de Hegel | Javier Fabo Lanuza Ateísmo, panteísmo, acosmismo y monoteísmo en la filosofía de Hegel (Comentario de un conocido pasaje sobre Spinoza) PhD. Javier Fabo Lanuza. Universidad Complutense de Madrid ([email protected]) Resumen Abstract Ateísmo y panteísmo son sistemáticamente Atheism, pantheism, acosmism and rechazados por Hegel a lo largo de su obra. monotheism in Hegel's philosophy Testimonio paradigmático de este rechazo es la (Commentary on a well-known Anm. del § 573 de la Enz., en la que el filósofo critica duramente el panteísmo, a la vez que se passage on Spinoza) desmarca netamente del ateísmo. Ello no ha impedido que los más afines a su filosofía Atheism and pantheism have been vieran en su crítica de la religión una systematically rejected by Hegel throughout his declaración de ateísmo, ni tampoco que su work. The Anm. of § 573 of the Enz. is a idealismo absoluto apareciera a ojos de los más paradigmatic testimony of this rejection, in críticos como una suerte de panteísmo which the philosopher strongly criticizes soterrado, sospechosamente afín a lo que Heine pantheism, and at the same time he clearly 267 llamaba «la religión secreta de Alemania». El distances himself from atheism. This has not Nº 101 propósito de este artículo es mostrar los prevented those closest to his philosophy from Julio-agosto 2021 malentendidos que subyacen a estas seeing in his critique of religion a declaration of interpretaciones, analizando los pasajes que atheism, nor has his absolute idealism appear to han contribuido a suscitarlas, de entre los que the most critical eyes as a kind of buried destaca el célebre elogio a Spinoza de las pantheism, suspiciously akin to what Heine Lecciones berlinesas, erróneamente tomado called «the secret religion of Germany».