A Remarkable Arctic Voyage Author(S): Clements R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report for Sy Hetairos Expedition in the Northwest Passage Permit 2016-15A

FINAL REPORT FOR SY HETAIROS EXPEDITION IN THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE PERMIT 2016-15A DATES OF TRIP: 8TH OF AUGUST 2016 TO 2ND OF SEPTEMBER 2016 AUTHOR OF REPORT: CECILIA VANMAN, EXPEDITION LEADER WITH EYOS EXPEDITIONS PERMIT NUMBER: 2016-15A Executive summary: EYOS ExpeDitions proviDeD guiDing services During a crossing of the Northwest Passage in Canada aboarD the private sailing yacht HETAIROS During 8th of August through to the 2nD of September, when the vessel was in the Nunavut region. UnDer Nunavut Archaeology Permit 2016-15A lanDings were authorizeD at: 1. Beechey IslanD, NorthumberlanD House, Devon IslanD 2. Beechey IslanD, Franklin ExpeDition Camp anD Graves, Devon IslanD 3. Fort Ross, Somerset IslanD, HBC Trading Post 4. Caswall Tower, Thule Site, Devon IslanD 5. DunDas Harbour, Morin Point, Devon IslanD (RCPM Detachment anD Thule site) Alternates: Port LeopolD, HBC Post anD Whaler’s grave As the permit holDer, Cecilia Vanman acteD as ExpeDition Leader for this private journey anD was hireD through Eyos ExpeDition for the SY HETAIROS Northwest Passage sail. Cecilia Vanman briefeD all guests on site visitation protocols prior to lanDings anD she is proviDing the information for this report. For all zoDiac lanDings we were no more than 10 people anD all regulations anD recommenDeD Distances anD protocols were uphelD During site visits. Cecilia Vanman monitoreD all people movements During site visits as the group was consiDereD relatively small. SITE VISITATIONS 1. Beechey IslanD, NorthumberlanD House, Devon IslanD 2. Beechey IslanD, Franklin ExpeDition Camp anD Graves, Devon IslanD 3. Fort Ross, Somerset IslanD, HBC Trading Post 4. DunDas Harbour, Morin Point, Devon IslanD (RCPM Detachment anD Thule site) Please see attacheD PDF maps of lanDings anD walking routes on sites. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Frederick J. Krabbé, Last Man to See HMS Investigator Afloat, May 1854

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society January 2017 Frederick J. Krabbé, last man to see HMS Investigator afloat, May 1854 William Barr1 and Glenn M. Stein2 Abstract Having ‘served his apprenticeship’ as Second Master on board HMS Assistance during Captain Horatio Austin’s expedition in search of the missing Franklin expedition in 1850–51, whereby he had made two quite impressive sledge trips, in the spring of 1852 Frederick John Krabbé was selected by Captain Leopold McClintock to serve under him as Master (navigation officer) on board the steam tender HMS Intrepid, part of Captain Sir Edward Belcher’s squadron, again searching for the Franklin expedition. After two winterings, the second off Cape Cockburn, southwest Bathurst Island, Krabbé was chosen by Captain Henry Kellett to lead a sledging party west to Mercy Bay, Banks Island, to check on the condition of HMS Investigator, abandoned by Commander Robert M’Clure, his officers and men, in the previous spring. Krabbé executed these orders and was thus the last person to see Investigator afloat. Since, following Belcher’s orders, Kellett had abandoned HMS Resolute and Intrepid, rather than their return journey ending near Cape Cockburn, Krabbé and his men had to continue for a further 140 nautical miles (260 km) to Beechey Island. This made the total length of their sledge trip 863½ nautical miles (1589 km), one of the longest man- hauled sledge trips in the history of the Arctic. Introduction On 22 July 2010 a party from the underwater archaeology division of Parks Canada flew into Mercy Bay in Aulavik National Park, on Banks Island, Northwest Territories – its mission to try to locate HMS Investigator, abandoned here by Commander Robert McClure in 1853.3 Two days later underwater archaeologists Ryan Harris and Jonathan Moore took to the water in a Zodiac to search the bay, towing a side-scan sonar towfish. -

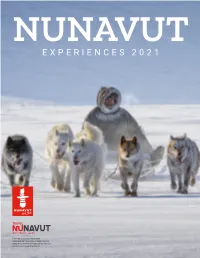

EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents

NUNAVUT EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents Arts & Culture Alianait Arts Festival Qaggiavuut! Toonik Tyme Festival Uasau Soap Nunavut Development Corporation Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum Malikkaat Carvings Nunavut Aqsarniit Hotel And Conference Centre Adventure Arctic Bay Adventures Adventure Canada Arctic Kingdom Bathurst Inlet Lodge Black Feather Eagle-Eye Tours The Great Canadian Travel Group Igloo Tourism & Outfitting Hakongak Outfitting Inukpak Outfitting North Winds Expeditions Parks Canada Arctic Wilderness Guiding and Outfitting Tikippugut Kool Runnings Quark Expeditions Nunavut Brewing Company Kivalliq Wildlife Adventures Inc. Illu B&B Eyos Expeditions Baffin Safari About Nunavut Airlines Canadian North Calm Air Travel Agents Far Horizons Anderson Vacations Top of the World Travel p uit O erat In ed Iᓇᓄᕗᑦ *denotes an n u q u ju Inuit operated nn tau ut Aula company About Nunavut Nunavut “Our Land” 2021 marks the 22nd anniversary of Nunavut becoming Canada’s newest territory. The word “Nunavut” means “Our Land” in Inuktut, the language of the Inuit, who represent 85 per cent of Nunavut’s resident’s. The creation of Nunavut as Canada’s third territory had its origins in a desire by Inuit got more say in their future. The first formal presentation of the idea – The Nunavut Proposal – was made to Ottawa in 1976. More than two decades later, in February 1999, Nunavut’s first 19 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) were elected to a five year term. Shortly after, those MLAs chose one of their own, lawyer Paul Okalik, to be the first Premier. The resulting government is a public one; all may vote - Inuit and non-Inuit, but the outcomes reflect Inuit values. -

Wolf-Sightings on the Canadian Arctic Islands FRANK L

ARCTIC VOL. 48, NO.4 (DECEMBER 1995) P. 313–323 Wolf-Sightings on the Canadian Arctic Islands FRANK L. MILLER1 and FRANCES D. REINTJES1 (Received 6 April 1994; accepted in revised form 13 March 1995) ABSTRACT. A wolf-sighting questionnaire was sent to 201 arctic field researchers from many disciplines to solicit information on observations of wolves (Canis lupus spp.) made by field parties on Canadian Arctic Islands. Useable responses were obtained for 24 of the 25 years between 1967 and 1991. Respondents reported 373 observations, involving 1203 wolf-sightings. Of these, 688 wolves in 234 observations were judged to be different individuals; the remaining 515 wolf-sightings in 139 observations were believed to be repeated observations of 167 of those 688 wolves. The reported wolf-sightings were obtained from 1953 field-weeks spent on 18 of 36 Arctic Islands reported on: no wolves were seen on the other 18 islands during an additional 186 field-weeks. Airborne observers made 24% of all wolf-sightings, 266 wolves in 48 packs and 28 single wolves. Respondents reported seeing 572 different wolves in 118 separate packs and 116 single wolves. Pack sizes averaged 4.8 ± 0.28 SE and ranged from 2 to 15 wolves. Sixty-three wolf pups were seen in 16 packs, with a mean of 3.9 ± 2.24 SD and a range of 1–10 pups per pack. Most (81%) of the different wolves were seen on the Queen Elizabeth Islands. Respondents annually averaged 10.9 observations of wolves ·100 field-weeks-1 and saw on average 32.2 wolves·100 field-weeks-1· yr -1 between 1967 and 1991. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Karte des Arktischen Archipel's der Parry-Inseln nach den bis zum Jarhe 1855 gewonnenen Resultaten Englisher Aufnahmen gezeichnet von A. Petermann Stock#: 42130 Map Maker: Petermann Date: 1855 Place: Gotha Color: Color Condition: VG Size: 22.5 x 10 inches Price: SOLD Description: Rare German Map of the Northwest Passage Scarce separately-published map of the Arctic Region, extending from Baffin Bay to Banks Straits and Prince Patrick Island. The map was published by August Petermann. Petermann was trained and worked for much of his life in Germany, but he began his cartographic career in Britain (Edinburgh and London) and advised many of the British Arctic expeditions of the 1840s and early 1850s. This interest in exploration is evident, as the map is littered with notes about which explorers first encountered which islands. There is also a color-coded key highlighting the voyages of: Red: Sir Edward E. Belcher -- August 14, 1852 to June 22, 1853 Yellow: G.H. Richarsd & S.H. Osborn -- April 10, 1853 to July 15, 1853 Orange: F.L. McClintock -- Apirl 4, 1853 to July 18, 1853 Blue: G.F. Mecham -- April 4, 1853 to July 6, 1853 Purple: R.V. Hamilton -- April 27 to June 21, 1853. The map also references earlier expeditions. For example, the title of the map references the Parry Islands. These are now known as the Queen Elizabeth Islands. Originally, they were named for British Arctic explorer William Edward Parry who, in 1819, got as far as Melville Island before being blocked by ice. -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

Glacial and Sea Level History of Lowther and Griffith Islands

Document generated on 09/29/2021 10:50 p.m. Géographie physique et Quaternaire Glacial and Sea Level History of Lowther and Griffith Islands, Northwest Territories: A Hint of Tectonics Histoire glaciaire et évolution des niveaux marins aux îles Lowther et Griffith, Territoires du Nord-Ouest : quelques indices de tectonique Glazialgeschichte und Entwicklung des Meeresspiegels auf den Insein Lowther und Griffith, Northwest Territories: Ein Hinweis auf die Tektonik Arthur S. Dyke Volume 47, Number 2, 1993 Article abstract Lowther and Griffith islands, in the centre of Parry Channel, were overrun by URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032944ar the Laurentide Ice Sheet early in the last glaciation. Northeastward Laurentide DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/032944ar ice flow persisted across at least Lowther Island until early Holocene déglaciation. Well constrained postglacial emergence curves for the islands See table of contents confirm a southward dip of raised shorelines, contrary to the dip expected from the ice load configuration. This and previously reported incongruities may indicate regionally extensive tectonic complications of postglacial Publisher(s) rebound aligned with major structural elements in the central Canadian Arctic Islands. Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal ISSN 0705-7199 (print) 1492-143X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Dyke, A. S. (1993). Glacial and Sea Level History of Lowther and Griffith Islands, Northwest Territories: A Hint of Tectonics. Géographie physique et Quaternaire, 47(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.7202/032944ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 1993 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

Schedule a Nunavut Land Use Plan Land Use Designations

65°W 70°W 60°W 75°W Alert ! 80°W 51 130 60°W Schedule A 136 82°N Nunavut Land Use Plan 85°W Land Use Designations 90°W 65°W Protected Area 82°N 95°W Special Management Area 135 134 80°N Existing Transportation Corridors 70°W 100°W ARCTIC 39 Proposed Transportation Corridors OCEAN 80°N Eureka ! 133 30 Administrative Boundaries 105°W 34 Area of Equal Use and Occupancy 110°W Nunavut Settlement Area Boundary 39 49 49 Inuit Owned Lands (Surface and Subsurface including minerals) 42 Inuit Owned Lands (Surface excluding minerals) 78°N 75°W 49 78°N 49 Established Parks (Land Use Plan does not apply) 168 168 168 168 168 168 49 49 168 39 168 168 168 168 168 168 39 168 49 49 49 39 42 39 39 44 168 39 39 39 22 167 37 70 22 18 Grise Fiord 44 18 168 58 58 49 ! 44 49 37 49 104 49 49 22 58 168 22 49 167 49 49 4918 76°N M 76°N 49 18 49 ' C 73 l u 49 28 167 r e 49 58 S 49 58 t r 49 58 a 58 59 i t 167 167 58 49 49 32 49 49 58 49 49 41 31 49 58 31 49 74 167 49 49 49 49 167 167 167 49 167 49 167 B a f f i n 49 49 167 32 167 167 167 B a y 49 49 49 49 32 49 32 61 Resolute 49 32 33 85 61 ! 1649 16 61 38 16 6138 74°N 74°N nd 61 S ou ter 61 nc as 61 61 La 75°W 20 61 69 49 49 49 49 14 49 167 49 20 49 61 61 49 49 49167 14 61 24 49 49 43 49 72°N 49 43 61 43 Pond Inlet 70°W 167 167 !49 ! 111 111 O Arctic Bay u t 167 167 e 49 26 r 49 49 29 L a 49 167 167 n 29 29 d 72°N 49 F 93 60 a Clyde River s 65°W 49 ! t 167 M ' C 60 49 I c l i e n 49 49 t 167 o c 72 k Z 49 o C h n 120°W a 70°N n e n 68°N 115°W e 49 l 49 Q i k i q t a n i 23 70°N 162 10 23 49 167 123 110°W 47 156 -

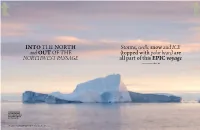

Storms, Swells, Snowand Ice (Topped with Polar Bears)

travel at home travel at home INTO THE NORTH Storms, swells, snow and ICE and OUT OF THE (topped with polar bears) are NORTHWEST PASSAGE all part of this EPIC voyage STORY + PHOTOGRAPHY BY Barb Sligl Iceberg at sunset, 250 km north of the Arctic Circle in Ilulissat Icefjord in Greenland, a UNESCO World Heritage Site 36 JUST FOR CANADIAN DENTISTS November/December 2016 travel at home travel at home omewhere above the Arctic Circle, I see a fata morgana. Low-lying, barren islands—like so many sperm whales with their broad, sloping foreheads—float above the horizon in Coronation Gulf. As if I’m a long-lost sea captain of yore, it’s a glimpse of what’s called a superior mirage. In 1818, on his search for the long-sought Northwest Passage, captain John Ross’s route was barred by an insurmountable range he called Croker’s Mountains. Yet there was no such thing. A year later, another explorer sailed right through the same spot in Lancaster Sound, as did doomed Franklin in 1845 and then the first man to make it through the SNorthwest Passage in 1906, Roald Amundsen. Today, this storied route is often still blocked—by sea ice. It’s what makes it one of the last untouched places on earth. I’m on Adventure Canada’s Out of the Northwest Passage voyage, and after my fata morgana sighting, I continue to see fantastical things over the next 16 days of this historic- yet-still-novel voyage. From a strip of pink on the horizon that hovers between inky sea and dark swathe of clouds like a Rothko painting to storms and swells, snow and ice—all High Arctic sunset, like a Rothko painting Touring Ilulissat Icefjord by zodiac with the seductive whisper of peril. -

Discover the Arctic & Make Your

DISCOVER THE ARCTIC & MAKE YOUR MAP Learn how as you explore the unGoogle-able Arctic ABOARD NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EXPLORER I 2017-18 TM THE ARCTIC DRAWS ADVENTUROUS TRAVELERS LIKE MOTHS TO LIGHT—perhaps because it’s dazzlingly white, and tantalizingly blank. It’s one of the last regions to have eluded the Google Earth cartographers: it remains a geography that insists on being discovered in person. Allow yourself to be drawn there—to the Arctic’s vivid blankness. Join us to explore the planet’s most inspiring geography, and feel your own capacity for wonder expand beyond all known borders. Guests have a water-level view of a huge iceberg in Ilulissat. ELLESMERE ISLAND JUST ADDED! THE ART OF MAPMAKING WITH NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EXPERTS 80° NORTH For cartographers, a map is a lens through which to view the natural and human world. As we venture into the most remote and little-known regions of the Arctic, we’ll be joined by a stellar Qaanaaq pair of experts: geographer, Stephen Cunha, and his wife, Mary Beth Cunha, a master cartographer. Adding extra insight to our team’s expertise—they will illuminate the history and challenges of mapping the Arctic. Delve into the DEVON ISLAND evolution of cartography, from the carved bones of the Inuit to the GIS technology of today. Learn Baffin Bay Lancaster Bylot mapmaking techniques and create physical and Sound Island digital maps you can bring home. Or take a more personal route— to create an emotional map of Pond Inlet the Arctic you discover. Qilakitsoq BAFFIN ISLAND Stephen Cunha and Mary Beth Cunha join us on Ilulissat the Exploring Greenland and the Canadian High Arctic (pg. -

Canada Topographical

University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Canada: topographical maps 1: 250,000 The Map Collection of the University of Waikato Library contains a comprehensive collection of maps from around the world with detailed coverage of New Zealand and the Pacific : Editions are first unless stated. These maps are held in storage on Level 1 Please ask a librarian if you would like to use one: Coverage of Canadian Provinces Province Covered by sectors On pages Alberta 72-74 and 82-84 pp. 14, 16 British Columbia 82-83, 92-94, 102-104 and 114 pp. 16-20 Manitoba 52-54 and 62-64 pp. 10, 12 New Brunswick 21 and 22 p. 3 Newfoundland and Labrador 01-02, 11, 13-14 and 23-25) pp. 1-4 Northwest Territories 65-66, 75-79, 85-89, 95-99 and 105-107) pp. 12-21 Nova Scotia 11 and 20-210) pp. 2-3 Nunavut 15-16, 25-27, 29, 35-39, 45-49, 55-59, 65-69, 76-79, pp. 3-7, 9-13, 86-87, 120, 340 and 560 15, 21 Ontario 30-32, 40-44 and 52-54 pp. 5, 6, 8-10 Prince Edward Island 11 and 21 p. 2 Quebec 11-14, 21-25 and 31-35 pp. 2-7 Saskatchewan 62-63 and 72-74 pp. 12, 14 Yukon 95,105-106 and 115-117 pp. 18, 20-21 The sector numbers begin in the southeast of Canada: They proceed west and north. 001 Newfoundland 001K Trepassey 3rd ed. 1989 001L St: Lawrence 4th ed. 1989 001M Belleoram 3rd ed.