Rtment of 'History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potential Republicans: Reconstruction Printers of Columbia, South Carolina John Lustrea University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 Potential Republicans: Reconstruction Printers of Columbia, South Carolina John Lustrea University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Lustrea, J.(2017). Potential Republicans: Reconstruction Printers of Columbia, South Carolina. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4124 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Potential Republicans: Reconstruction Printers of Columbia, South Carolina By John Lustrea Bachelor of Arts University of Illinois, 2015 ___________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Thomas Brown, Director of Thesis Mark Smith, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by John Lustrea, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my dad. Thanks for supporting my love of history from an early age and always encouraging me to press on. iii Acknowledgements As with any significant endeavor, I could not have done it without assistance. Thanks to Dr. Mark Cooper for helping me get this project started my first semester. Thanks to Lewis Eliot for reading a draft and offering helpful comments. Thanks to Dr. Mark Smith for guiding me through the process of turning it into an article length paper, and thanks to Dr. -

The Texas Constitution, Adopted In

Listen on MyPoliSciLab 2 Study and Review the Pre-Test and Flashcards at myanthrolab The Texas Read and Listen to Chapter 2 at myanthrolab Listen to the Audio File at myanthrolab ConstitutionView the Image at myanthrolab Watch the Video at myanthrolab Humbly invoking the blessings of Almighty God, the people of the State of Texas do ordain and establish this Constitution. Read the Document at myanthrolab —Preamble to the Constitution of Texas 1876 If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, Maneitherp the Concepts at myanthrolab external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.Explore the Concept at myanthrolab —James Madison, Federalist No. 51 Simulate the Experiment at myanthrolab he year was 1874, and unusual events marked the end of the darkest chapter in Texas history—the Reconstruction era and the military occupation that followed the Civil War. Texans, still smarting from some of the most oppressive laws ever T imposed on U.S. citizens, had overwhelmingly voted their governor out of of- fice, but he refused to leave the Capitol and hand over his duties to his elected successor. For several tense days, the city of Austin was divided into two armed camps—those supporting the deposed governor, Edmund J. Davis, and thoseRead supporting the Document the man at my whoanthr defeatedolab Margin sample him at the polls, Richard Coke. -

Smash and Dash

WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE TheTUESDAY | JANUARY 29, 2013Baylor Lariatwww.baylorlariat.com SPORTS Page 5 NEWS Page 3 A&E Page 4 Making milestones It all adds up Ready, set, sing Brittney Griner breaks the NCAA Baylor accounting students Don’t miss today’s opening record for total career blocks. Find out land in the top five of a national performance of the Baylor how she affects the court defensively accounting competition Opera’s ‘Dialogues of Carmelites’ Vol. 115 No. 4 © 2013, Baylor University In Print >> HAND OFF Smash Alumni Association Baylor reacts to former Star Wars director George Lucas passing the director’s torch to J.J. and president under fire Abrams By Sierra Baumbach indirectly communicated to the prosecu- Staff Writer tor who was trying the case,” Polk County Page 4 Criminal District Attorney William Lee dash The 258th State District Judge Eliza- Hon wrote In an e-mail to the Lariat. beth E. Coker, who is also president of >> CALL OUT According to the Chronicle article, Local cemetery the Baylor Alumni Association, is under Polk County Investigator David Wells Get one writer’s opinion review by the Texas Commission on Judi- was sitting beside Jones in the gallery. on player safety and cial Conduct for a text message allegedly Jones asked to borrow Wells’ notepad the future of the NFL plagued by sent during court that was thought to aid and it was from this exchange that Wells following remarks by the prosecution in a felony charge of in- discovered the interaction between Cok- President Obama and vandalism jury to a child. -

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016 History of Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was created by the State Constitution of 1845 and the office holder is President of the Texas Senate.1 Origins of the Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was established with statehood and the Constitution of 1845. Qualifications for Office The Council of State Governments (CSG) publishes the Book of the States (BOS) 2015. In chapter 4, Table 4.13 lists the Qualifications and Terms of Office for lieutenant governors: The Book of the States 2015 (CSG) at www.csg.org. Method of Election The National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA) maintains a list of the methods of electing gubernatorial successors at: http://www.nlga.us/lt-governors/office-of-lieutenant- governor/methods-of-election/. Duties and Powers A lieutenant governor may derive responsibilities one of four ways: from the Constitution, from the Legislature through statute, from the governor (thru gubernatorial appointment or executive order), thru personal initiative in office, and/or a combination of these. The principal and shared constitutional responsibility of every gubernatorial successor is to be the first official in the line of succession to the governor’s office. Succession to Office of Governor In 1853, Governor Peter Hansborough Bell resigned to take a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and Lt. Governor James W. Henderson finished the unexpired term.2 In 1861, Governor Sam Houston was removed from office and Lt. Governor Edward Clark finished the unexpired term. In 1865, Governor Pendleton Murrah left office and Lt. -

The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network

PLATFORMS AND OUTSIDERS IN PARTY NETWORKS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE DIGITAL POLITICAL ADVERTISING NETWORK Bridget Barrett A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Daniel Kreiss Adam Saffer Adam Sheingate © 2020 Bridget Barrett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bridget Barrett: Platforms and Outsiders in Party Networks: The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network (Under the direction of Daniel Kreiss) Scholars seldom examine the companies that campaigns hire to run digital advertising. This thesis presents the first network analysis of relationships between federal political committees (n = 2,077) and the companies they hired for electoral digital political advertising services (n = 1,034) across 13 years (2003–2016) and three election cycles (2008, 2012, and 2016). The network expanded from 333 nodes in 2008 to 2,202 nodes in 2016. In 2012 and 2016, Facebook and Google had the highest normalized betweenness centrality (.34 and .27 in 2012 and .55 and .24 in 2016 respectively). Given their positions in the network, Facebook and Google should be considered consequential members of party networks. Of advertising agencies hired in the 2016 electoral cycle, 23% had no declared political specialization and were hired disproportionately by non-incumbents. The thesis argues their motivations may not be as well-aligned with party goals as those of established political professionals. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................................... V POLITICAL CONSULTING AND PARTY NETWORKS ............................................................................... -

Policy Report Texas Fact Book 2008

Texas Fact Book 2 0 0 8 L e g i s l a t i v e B u d g e t B o a r d LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD EIGHTIETH TEXAS LEGISLATURE 2007 – 2008 DAVID DEWHURST, JOINT CHAIR Lieutenant Governor TOM CRADDICK, JOINT CHAIR Representative District 82, Midland Speaker of the House of Representatives STEVE OGDEN Senatorial District 5, Bryan Chair, Senate Committee on Finance ROBERT DUNCAN Senatorial District 28, Lubbock JOHN WHITMIRE Senatorial District 15, Houston JUDITH ZAFFIRINI Senatorial District 21, Laredo WARREN CHISUM Representative District 88, Pampa Chair, House Committee on Appropriations JAMES KEFFER Representative District 60, Eastland Chair, House Committee on Ways and Means FRED HILL Representative District 112, Richardson SYLVESTER TURNER Representative District 139, Houston JOHN O’Brien, Director COVER PHOTO COURTESY OF SENATE MEDIA CONTENTS STATE GOVERNMENT STATEWIDE ELECTED OFFICIALS . 1 MEMBERS OF THE EIGHTIETH TEXAS LEGISLATURE . 3 The Senate . 3 The House of Representatives . 4 SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES . 8 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEES . 10 BASIC STEPS IN THE TEXAS LEGISLATIVE PROCESS . 14 TEXAS AT A GLANCE GOVERNORS OF TEXAS . 15 HOW TEXAS RANKS Agriculture . 17 Crime and Law Enforcement . 17 Defense . 18 Economy . 18 Education . 18 Employment and Labor . 19 Environment and Energy . 19 Federal Government Finance . 20 Geography . 20 Health . 20 Housing . 21 Population . 21 Social Welfare . 22 State and Local Government Finance . 22 Technology . 23 Transportation . 23 Border Facts . 24 STATE HOLIDAYS, 2008 . 25 STATE SYMBOLS . 25 POPULATION Texas Population Compared with the U .s . 26 Texas and the U .s . Annual Population Growth Rates . 27 Resident Population, 15 Most Populous States . -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

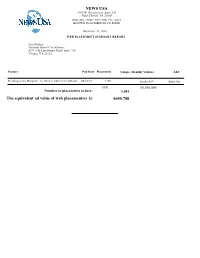

NEWS USA the Equivalent Ad Value of Web Placement(S)

NEWS USA 1069 W. Broadstreet, Suite 205 Falls Church, VA 22046 (800) 355 - 9500 / Fax (703) 734 - 6314 KNOWN PLACEMENTS TO DATE December 31, 2016 WEB PLACEMENT SUMMARY REPORT Lisa Fullam National Blood Clot Alliance 8321 Old Courthouse Road, Suite 255 Vienna, VA 22182 Feature Pub Date Placements Unique Monthly Visitors AEV Heading to the Hospital? Get Better. Don’t Get a Blood 08/10/16 1,001 50,058,999 $600,708 1001 50,058,999 Number of placements to date: 1,001 The equivalent ad value of web placement(s) is: $600,708 NEWS USA 1069 W. Broadstreet, Suite 205 Falls Church, VA 22046 (800) 355 - 9500 / Fax (703) 734 - 6314 KNOWN PLACEMENTS TO DATE December 31, 2016 National Blood Clot Alliance--Fullam WEB PLACEMENTS REPORT Feature: Heading to the Hospital? Get Better. Don’t Get a Blood Clot. Publication Date: 8/10/16 Unique Monthly Web Site City, State Date Vistors AEV 760 KFMB San Diego, CA 08/11/16 4,360 $52.32 96.5 Wazy ::: Today's Best Music, Lafayette Indiana Lafayette, IN 08/12/16 280 $3.36 Aberdeen American News Aberdeen, SD 08/11/16 14,800 $177.60 Abilene-rc.com Abilene, KS 08/11/16 0 $0.00 About Pokemon Go Cirebon, ID 09/08/16 0 $0.00 Advocate Tribune Online Granite Falls, MN 08/11/16 37,855 $454.26 aimmediatexas.com/ McAllen, TX 08/11/16 920 $11.04 Alerus Retirement Solutions Arden Hills, MN 08/12/16 28,400 $340.80 Alestle Live Edwardsville, IL 08/11/16 1,640 $19.68 Algona Upper Des Moines Algona, IA 08/11/16 680 $8.16 Amery Free Press. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

Cotwsupplemental Appendix Fin

1 Supplemental Appendix TABLE A1. IRAQ WAR SURVEY QUESTIONS AND PARTICIPATING COUNTRIES Date Sponsor Question Countries Included 4/02 Pew “Would you favor or oppose the US and its France, Germany, Italy, United allies taking military action in Iraq to end Kingdom, USA Saddam Hussein’s rule as part of the war on terrorism?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 8-9/02 Gallup “Would you favor or oppose sending Canada, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, American ground troops (the United States USA sending ground troops) to the Persian Gulf in an attempt to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 9/02 Dagsavisen “The USA is threatening to launch a military Norway attack on Iraq. Do you consider it appropriate of the USA to attack [WITHOUT/WITH] the approval of the UN?” (Figures represent average across the two versions of the UN approval question wording responding “under no circumstances”) 1/03 Gallup “Are you in favor of military action against Albania, Argentina, Australia, Iraq: under no circumstances; only if Bolivia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, sanctioned by the United Nations; Cameroon, Canada, Columbia, unilaterally by America and its allies?” Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, (Figures represent percent responding “under Finland, France, Georgia, no circumstances”) Germany, Iceland, India, Ireland, Kenya, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, Portugal, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Uganda, United Kingdom, USA, Uruguay 1/03 CVVM “Would you support a war against Iraq?” Czech Republic (Figures represent percent responding “no”) 1/03 Gallup “Would you personally agree with or oppose Hungary a US military attack on Iraq without UN approval?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 2 1/03 EOS-Gallup “For each of the following propositions tell Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, me if you agree or not. -

Civil War in the Lone Star State

page 1 Dear Texas History Lover, Texas has a special place in history and in the minds of people throughout the world. It has a mystique that no other state and few foreign countries have ever equaled. Texas also has the distinction of being the only state in America that was an independent country for almost 10 years, free and separate, recognized as a sovereign gov- ernment by the United States, France and England. The pride and confidence of Texans started in those years, and the “Lone Star” emblem, a symbol of those feelings, was developed through the adventures and sacrifices of those that came before us. The Handbook of Texas Online is a digital project of the Texas State Historical Association. The online handbook offers a full-text searchable version of the complete text of the original two printed volumes (1952), the six-volume printed set (1996), and approximately 400 articles not included in the print editions due to space limitations. The Handbook of Texas Online officially launched on February 15, 1999, and currently includes nearly 27,000 en- tries that are free and accessible to everyone. The development of an encyclopedia, whether digital or print, is an inherently collaborative process. The Texas State Historical Association is deeply grateful to the contributors, Handbook of Texas Online staff, and Digital Projects staff whose dedication led to the launch of the Handbook of Civil War Texas in April 2011. As the sesquicentennial of the war draws to a close, the Texas State Historical Association is offering a special e- book to highlight the role of Texans in the Union and Confederate war efforts.