Indigenous Round Highlights How Far AFL Has Come but There Is Still Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFL Footy Maths Rounds 18 – 20

AFL Footy Maths Rounds 18 – 20 The season is hotting up especially for those teams who want to play in the finals Rounds. Congratulations to Jordan Lewis, Bryce Gibbs, Alex Johnson and Nathan Freeman 1. In Round 19 Jordan Lewis (Melbourne) played his 300th game. In his career Jordan has played with Hawthorn and Melbourne. If he has played 36 games with Melbourne, how many games did he play with Hawthorn? Player Games played Melbourne Hawthorn Jordan Lewis 300 36 2. In Round 20 Bryce Gibbs (Adelaide) played his 250th game. In his career Bryce has played with Carlton and Adelaide. If he has played 19 games with Adelaide, how many games did he play with Carlton? Player Games played Adelaide Carlton Bryce Gibbs 250 19 3. Alex Johnson was relied after his long awaited AFL return. He last played 2136 days ago when he played in a Sydney final. Since his last game he has had 12 knee operations. In what year did he have his last game? a) 2016 b) 2012 c) 2014 d) 2013 Discuss your answer. Justify your solution 4. Nathan Freeman played his first AFL game with St Kilda for 1718 days after he was first drafted by Collingwood at pick 10. He has suffered years of hamstring related injuries. In what year was he drafted? e) 2016 f) 2012 g) 2014 h) 2013 Discuss your answer. Justify your solution 5. The leadership for the Coleman Medal is getting much closer after Lance Franklin kicked 6 goals in Round 20 and Tom Hawkins kicked 7 goals in both Rounds 18 and 19. -

Carlton Corporate Entertain | Network | Enjoy Contents

CARLTON CORPORATE ENTERTAIN | NETWORK | ENJOY CONTENTS MATCH-DAY HOSPITALITY CARLTON FOOTBALL CLUB MAJOR EVENTS Carlton President’s Club by Virgin Australia 6 AFLW Best and Fairest, The Carltonians 7 proudly presented by Big Ant Studios 27 Corporate Suites – MCG 9 John Nicholls Medal, proudly presented by Hyundai 27 Corporate Suites – Marvel Stadium 10 Carlton IN Business Grand Final Event 27 CORPORATE GROUPS AND VIP MEMBERSHIPS MORE FROM CARLTON CORPORATE Carlton IN Business 11 Carlton Respects 29 The Carltonians membership 14 Hyundai 31 Navy League 15 Branding and Partnerships 32 Sydney Blues 16 Blues Forever 33 Young Carlton Professionals 17 GUERNSEY CLUB AFL Senior Coach Ambassador 19 AFLW Senior Coach Ambassador 20 AFL Coaches Ambassador 21 AFL Player Sponsorship Platinum 22 AFL Player Sponsorship Gold 23 AFL Player Sponsorship Silver 24 AFLW Player Sponsorship 25 WELCOME TO CARLTON CORPORATE Football is set to return in a big way in 2021, and our team is working closely with the AFL to prepare for a return to the rivalries, experiences and rituals we’ve grown to love. The Carlton Corporate team is eager to welcome you back to the footy next year, with a raft of exciting products and VIP memberships to suit all levels of investment. Our team is ready to begin tailoring solutions for your individual or corporate needs and will offer some of the best seats in the house for an unrivalled hospitality experience. To ensure you receive priority access to the biggest games, please contact one of our team members today to discuss your requirements and secure a booking.* We look forward to seeing you back at the footy in 2021! *All VIP membership benefits and corporate hospitality will be subject to AFL and State Government restrictions. -

Club and AFL Members Received Free Entry to NAB Challenge Matches and Ticket Prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series Were Held at 2013 Levels

COMMERCIAL OPERATIONS DARREN BIRCH GENERAL MANAGER Club and AFL members received free entry to NAB Challenge matches and ticket prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series were held at 2013 levels. eason 2015 was all about the with NAB and its continued support fans, with the AFL striving of the AFL’s talent pathway. to improve the affordability The AFL welcomed four new of attending matches and corporate partners in CrownBet, enhancing the fan experience Woolworths, McDonald’s and 2XU to at games. further strengthen the AFL’s ongoing SFor the first time in more than 10 development of commercial operations. years, AFL and club members received AFL club membership continued free general admission entry into NAB to break records by reaching a total of Challenge matches in which their team 836,136 members nationally, a growth was competing, while the price of base of 3.93 per cent on 2014. general admission tickets during the In season 2015, the Marketing and Toyota Premiership Season remained the Research Insights team moved within the same level as 2014. Commercial Operations team, ensuring PRIDE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA Fans attending the Toyota AFL Finals greater integration across membership, The Showdown rivalry between Eddie Betts’ Series and Grand Final were also greeted to ticketing and corporate partners. The Adelaide Crows and Port ticket prices at the same level as 2013, after a Research Insights team undertook more Adelaide continued in 2015, price freeze for the second consecutive year. than 60 projects, allowing fans, via the with the round 16 clash drawing a record crowd NAB AFL Auskick celebrated 20 years, ‘Fan Focus’ panel, to influence future of 53,518. -

Health and Physical Education

Resource Guide Health and Physical Education The information and resources contained in this guide provide a platform for teachers and educators to consider how to effectively embed important ideas around reconciliation, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions, within the specific subject/learning area of Health and Physical Education. Please note that this guide is neither prescriptive nor exhaustive, and that users are encouraged to consult with their local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and critically evaluate resources, in engaging with the material contained in the guide. Page 2: Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 3: Timeline of Key Dates in the more Contemporary History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Organisations, Programs and Campaigns Page 6: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sportspeople Page 8: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Events/Celebrations Page 12: Other Online Guides/Reference Materials Page 14: Reflective Questions for Health and Physical Education Staff and Students Please be aware this guide may contain references to names and works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that are now deceased. External links may also include names and images of those who are now deceased. Page | 1 Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education “[Health and] healing goes beyond treating…disease. It is about working towards reclaiming a sense of balance and harmony in the physical, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual works of our people, and practicing our profession in a manner that upholds these multiple dimension of Indigenous health” –Professor Helen Milroy, Aboriginal Child Psychiatrist and Australia’s first Aboriginal medical Doctor. -

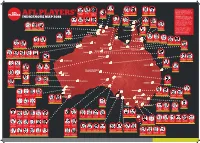

To Access the 2018 Aflpa Indigenous

NB: Player images may appear twice as players have provided information for Nakia Cockatoo multiple language and/or cultural groups. GEELONG Jed Anderson Brandan Parfitt Ben Davis Alicia Janz Refer to AFL Players’ website to view the Anthony McDonald- Allen Christensen Ben Long NORTH GEELONG ADELAIDE FREMANTLE Interactive Indigenous Players’ Map — BRISBANE ST KILDA Tipungwuti MELBOURNE AFL PLAYERS’ ESSENDON www.aflplayers.com.au Shaun Burgoyne DISCLAIMER : This map indicates only INDIGENOUS MAP 2018 HAWTHORN the general location of larger groupings of people, which may include smaller groups such as clans, dialects or individual Meriam Mìr languages in a group. Boundaries are not intended to be exact. For more detailed Jake Neade information about the groups of people Daniel Rioli Sean Lemmens Cyril Rioli Willie Rioli PORT Ruth Wallace Nakia Cockatoo in a particular region contact the relevant RICHMOND HAWTHORN WEST COAST ADELAIDE ADELAIDE GOLD COAST Tiwi GEELONG Jarrod Harbrow land council. Not suitable for use in native GOLD COAST title and other land claims. Wuthathi Names and regions as used in the Iwaidja Jay Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia Steven May Steven Motlop Brandan Parfitt Kennedy-Harris (D. Horton, General Editor) published GOLD COAST PORT ADELAIDE GEELONG MELBOURNE in 1994 by the Australian Institute of Larrakia Yupangathi Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Warray Studies (Aboriginal Studies Press) Marunnungu Joel Garner GPO Box 553 Canberra, Act 2601. PORT Marrithiyel ADELAIDE Jake Long ESSENDON Yidinjdi Nakia -

Tuesday, June 16, 2020

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI TUESDAY, JUNE 16, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 MPS’ PAY CUTS UNTIDY YET TO KICK IN KIWI PAGE 6 A PILE of household goods including washing machines, ovens and mattresses was found dumped at the southern end of Makorori Beach on NZ NEEDS TO BE Saturday. The person who found the rubbish took photos and shared it on Facebook ‘COURAGEOUS’ to start a public discussion about PAGE 3 solutions or preventative measures. Rubbish was also dumped at Okitu Reserve carpark some weeks ago. A Gisborne District Council spokesperson said 13 requests for service to deal with rubbish dumping at Makorori had been received in the past 12 months, including two in 2020. NZERS DRAIN KIWISAVER ACCOUNTS PAGE 10 Judge rejects application for discharge DEFUNCT forestry company submisssions were required as practice is a matter of real DNS Forest Products Limited to whether provisions in the importance, he said. FACING has been convicted and faces Companies Act might preclude There were extensive a fine of $124,700 for water the penalties being imposed. plantings on vulnerable pollution caused by poor The court also needed land and forestry operations harvesting practice at its to consider whether under continue on a large scale Makiri Forest, two years ago. the circumstances it might throughout this region, the In Gisborne District Court alternatively impose a judge said. Sentencings for yesterday, Judge Brian conviction and discharge, but offending such as this must FINE FOR Dwyer rejected the company’s that was not his preference, the be set at a level that drives application for a discharge judge said. -

Abstract This Article Presents the Findings of 2,415 Posts Collected

Abstract This article presents the findings of 2,415 posts collected from two prominent Australian Football League message boards that responded to a racist incident involving a banana being thrown at Adelaide Crows player, Eddie Betts, in August 2016. It adopts Bourdieu’s concept of habitus to examine the online practice of fans for evidence of racist discourse and the extent to which this was supported or contested by fellow fans. The overall findings are that online debates about race in Australian Rules Football and wider Australian society remain divided, with some posters continuing to reflect racial prejudice and discrimination towards non-whites. However, for the vast majority, views deemed to have racist connotations are contested and challenged in a presentation centering on social change and racial equality. Port Adelaide have indefinitely banned the woman who ignited a racism controversy by throwing a banana at Indigenous star Eddie Betts. The Power completed an investigation into the ugly incident after speaking with the club member on Sunday, concluding it was racially motivated. Betts was targeted by the fan in Saturday night’s 15-point Showdown victory by the Crows at Adelaide Oval. The supporter was seen waving her middle finger at Betts before throwing the banana in his direction. Betts had just kicked his fifth goal in a near best-afield showing during his 250th AFL game, and did not notice the incident. Port Adelaide chairman David Koch said before the club spoke with the woman that he’d be “absolutely disgusted” if racism was found to be the motivation. “We’re a club, we’re an industry, we’re a code that doesn’t shirk away from these sorts of incidents,” he said. -

MIDFIELDERS DEFENDERS RUCKS NAME 2014 AVE NAME 2014 AVE NAME 2014 AVE Gary Ablett 136.7 Nick Malceski 105.4 Sam Jacobs 115.4

MIDFIELDERS DEFENDERS RUCKS NAME 2014 AVE NAME 2014 AVE NAME 2014 AVE Gary Ablett 136.7 Nick Malceski 105.4 Sam Jacobs 115.4 Tom Rockliff 132 Kade Simpson 95.4 Shane Mumford 114.2 Scott Pendlebury 124.4 Shaun Burgoyne 94.2 Stef Martin 111.7 Nat Fyfe 122.3 Brodie Smith 93.5 Aaron Sandilands 108 Joel Selwood 120.9 Heath Shaw 96.2 Todd Goldstein 106.9 Danye Beams 115.5 Josh Gibson 92.5 Paddy Ryder 101.1 Rory Sloane 114.8 Luke Hodge 91.5 Matthew Lobbe 100 Josh Kennedy 113.9 Michael Hibberd 91.4 Ivan Maric 99.7 Steele Sidebottom 113.2 Matthew Jaensch 89.5 Will Minson 93.3 Matthew Priddis 112.8 Corey Enright 89 Nic Naitanui 90.8 Callan Ward 112.8 Grant Birchall 88.9 Ben McEvoy 89.8 Michael Barlow 111.7 James Kelly 88.9 Hamish McIntosh 83.8 Jordan Lewis 109.4 Alex Rance 88.6 Mark Jamar 82.8 Luke Parker 108.5 Bob Murphy 88.5 Robbie Warnock 80.9 Nathan Jones 108.1 Paul Duffield 88.4 Tom Hickey 88.3 Adam Treloar 107.5 Andrew Walker 87.2 Mike Pyke 77.7 Jobe Watson 106.7 Michael Johnson 87.2 Jon Ceglar 76.7 Steve Johnson 106.7 Shannon Hurn 86.9 Zac Smith 76.2 Dyson Heppell 106.4 Andrew Mackie 86.1 Shaun Hampson 75.9 Bryce Gibbs 106.2 Michael Hurley 85.7 Zac Clarke 75.9 Marc Murphy 106 Jeremy Howe 85.4 Dion Prestia 106.8 Lynden Dunn 85.2 WATCH LIST Travis Boak 105.7 Bachar Houli 83.2 NAME 2014 AVE Patrick Dangefield 105.6 Ryan Harwood 83.2 Rhyce Shaw 74.4 Jarrad McVeigh 104.5 Harry Taylor 83.1 Tom Langdon 71 Pearce Hanley 103.8 Sam Fisher 92 Shane Savage 69.1 David Swallow 103.2 Chris Yarran 82.7 Kade Kolodjashnij 68.4 Jack Redden 103.1 Jeremy McGovern -

AFL Trivia Quiz

Indoor wet weather ideas: AFL Trivia Quiz (May need pens/pencils and paper to write on) DFS Chinese boxing competition DFS Ricochet Round Robin Team Song performance (Players SHP teams for the day) Sing their AFL club song performance/competition Arm Tangle Competition AFL Trivia Quiz NOTE: Groups may need writing materials. (Pen/pencil, paper). Otherwise, they discuss then verbally say their answer. 1. Who won the 2016 AFL Grand Final? Western Bulldogs 2. Who won the 2016 Brownlow Medal? Patrick Dangerfield 3. Who won the 2016 Coleman Medal? Josh J Kennedy 4. Who won the 2016 Norm Smith Medal? Jason Johannisen 5. Which player holds the record for most goals ever kicked? Tony Lockett 6. Which clubs did he play for? St Kilda (898 goals) & Sydney (462) 7. What are the traditional colours of the Gold Coast Suns? Red, Gold, Blue 8. Who have won the most AFL premierships? Essendon, Carlton (16) 9. Who is the current captain of the Western Bulldogs? Bob Murphy 10. How many games did Essendon win last year? 3 matches 11. Who is the current coach Geelong (first and last name!)? Chris Scott 12. What is Gary Ablett jun Gary Ablett 13. How many draws have their been this AFL season? 0 (Check that a draw happen on weekend!) 14. What number draft pickior’s did Dad’sRichmond name? pick Trent Cotchin? Pick 2 15. Which club did Anthony Koutoufides play for? Carlton didn’t 16. Which AFL club did Andrew Macleod play for? Adelaide Crows 17. What are the traditional colours of the St. -

1. a Field Umpire Runs on Average 10 - 15 Kilometres When Officiating an AFL Game

1. A field umpire runs on average 10 - 15 kilometres when officiating an AFL game. Eleni Gloftsis is expected to umpire her second game next week in Round 10 If she runs 10 kilometres a game how many kilometres will she have run in her first two games? Games Kilometres Total x = If she runs 12.5 kilometres a game, how many kilometres will she have run in her first two games? Games Kilometres Total x = If she runs 15 kilometres a game, how many kilometres will she have run in her first two games? Games Kilometres Total x = 2. The AFL already has three female umpires in its ranks with Chelsea Roffey, Rose O'Dea and Sally Boud. They are goal umpires. Over the past two seasons Eleni Gloftsis has umpired 33 VFL matches. If she runs 10 kilometres a game how many kilometres will she have run in her 33 games? Games Kilometres Total x = If she runs 12.5 kilometres a game, how many kilometres will she have run in her 33 games? Games Kilometres Total x = If he runs 15 kilometres a game, how many kilometres will she have run in her 33 games? Games Kilometres Total x = 3. In Round 8 James Kelly formerly of Geelong and now playing with Essendon played his 300 AFL game. If he has played 27 games for Essendon, how many games did he play for Geelong? Let’s look at this match Team 1st quarter 2nd quarter 3rd quarter 4th quarter Total score Essendon 6.2 9.4 14.7 17.8 Geelong 1.5 3.8 7.9 13.15 After half time which team scored Who won the match? What was the winning score? the most? In Round 8 two teams scored 110 points. -

AFL Vic Record Week 14.Indd

VFL Round 10 TAC Cup Round 11 20 - 21 June 2015 $3.00 Photo: Shane Goss Photo: Morgan Hancock Features 4 5 Phil Dunk 7 James Magner 9 Darcy Tucker 12 Brent Wallace Every week Editorial 3 VFL Highlights 10 VFL News 11 AFL Vic News 13 TAC Cup Highlights 14 TAC Cup News 15 Club Whiteboard 16 19 Events 21 Connect with your club 22 23 Draft Watch 64 Who’s playing who 34 35 Richmond vs Footscray 52 53 Eastern vs Oakleigh 36 37 North Ballarat vs Casey Scorpions 54 55 Murray vs Geelong 38 39 Coburg vs Geelong 56 57 Dandenong vs North Ballarat 40 41 Northern Blues vs Werribee 58 59 Bendigo vs Gippsland 42 43 Frankston vs Port Melbourne 60 61 Northern vs Western 44 45 Williamstown vs Box Hill Hawks 62 63 Sandringham vs Calder Editor: Ben Pollard ben.pollard@afl vic.com.au Contributors: Dave O’Neill, Anthony Stanguts, Design & Print: Cyan Press Photos: AFL Photos (unless otherwise credited) Ikon Park, Gate 3, Royal Parade, Carlton Nth, VIC 3054 Advertising: Ryan Webb (03) 8341 6062 GPO Box 4337, Melbourne, VIC 3001 Phone: (03) 8341 6000 | Fax: (03) 9380 1076 AFL Victoria CEO: Steven Reaper www.afl vic.com.au State League & Talent Manager: John Hook High Performance Managers: Anton Grbac, Leon Harris Cover: Trent Dennis-Lane has eyes only for the ball in Sandringham’s Round 9 win over Port Melbourne. Talent Operations Coordinator: Rhy Gieschen Photo: Dave Savell Talent Operations Coordinator: Lauren Bunting www.taccup.com.au 01 Television Online VFL Online Website: www.vfl .com.au Twitter: @VFL #PJVFL Facebook: www.facebook.com/vfl footy Broadcasting -

AFL Insights

AFL Season Wrap OCTOBER 2020 GEMBA© - AFL SEASON WRAP 2 Despite not quite reaching the Grand Final, Brisbane’s fanatical supporter base grew by 28% during 2020 as fans responded to success TEAM SUPPORT MARKET SIZE (2020) | AFL FANATICS AGED 16+ Club Fanatics (Sept 2020) Sydney 667,615 Collingwood 583,480 Adelaide 514,296 Brisbane 503,871 +28% West Coast Eagles 405,329 Richmond 397,518 Carlton 372,433 Geelong 367,268 Essendon 332,743 Melbourne 282,300 Western Bulldogs 205,498 KEY INSIGHT Hawthorn 199,452 6% of AFL fans in Gold Coast 191,742 Queensland didn’t support Fremantle 173,969 North Melbourne 149,616 a team during Jan to Mar, Port Adelaide 130,231 compared to only 3% St Kilda 119,620 during July to September GWS Giants 77,968 None 149,389 - 100,000 200,000 300,000 400,000 500,000 600,000 700,000 Gemba defines fan base size based on survey respondents rating their passion for AFL as 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale. While those rated 3 are classified as fans, we focus on the more engaged “fanatics” that drive the majority of consumption and expenditure in the AFL economy. Source: Gemba Insights Program GEMBA© - AFL SEASON WRAP 3 Metro free-to-air audiences exceeded 2019 during the first round of finals, with Seven capturing its highest Brisbane audience in 11 years FTA BROADCAST TRENDS | AFL FINALS 2500 Brisbane ↑50% YoY Seven’s highest audience in Brisbane 2000 in 11 years (excluding Grand Finals). 500k more metro viewers tuned in to the AFL week 1 final, leaving Penrith v Roosters qualifying NRL final short on 1500 viewers ↑12% on 2019