Michael Dewar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward M. Eyring

The Chemistry Department 1946-2000 Written by: Edward M. Eyring Assisted by: April K. Heiselt & Kelly Erickson Henry Eyring and the Birth of a Graduate Program In January 1946, Dr. A. Ray Olpin, a physicist, took command of the University of Utah. He recruited a number of senior people to his administration who also became faculty members in various academic departments. Two of these administrators were chemists: Henry Eyring, a professor at Princeton University, and Carl J. Christensen, a research scientist at Bell Laboratories. In the year 2000, the Chemistry Department attempts to hire a distinguished senior faculty member by inviting him or her to teach a short course for several weeks as a visiting professor. The distinguished visitor gets the opportunity to become acquainted with the department and some of the aspects of Utah (skiing, national parks, geodes, etc.) and the faculty discover whether the visitor is someone they can live with. The hiring of Henry Eyring did not fit this mold because he was sought first and foremost to beef up the graduate program for the entire University rather than just to be a faculty member in the Chemistry Department. Had the Chemistry Department refused to accept Henry Eyring as a full professor, he probably would have been accepted by the Metallurgy Department, where he had a courtesy faculty appointment for many years. Sometime in early 1946, President Olpin visited Princeton, NJ, and offered Henry a position as the Dean of the Graduate School at the University of Utah. Henry was in his scientific heyday having published two influential textbooks (Samuel Glasstone, Keith J. -

Tribute to Josef Michl

Editorial Editorial TributeTribute to JosefJosef Michl Michl IgorIgor Alabugin Alabugin 1,1,** andand Petr Petr Klán Klá n2,*2, * 1 1 Department of of Chemistry Chemistry and and Biochemistry, Biochemistry, Florida Florida State University,State University, Tallahassee, Tallahassee, Fl 32306, Fl USA 32306, USA 2 2 Department of of Chemistry Chemistry and and RECETOX, RECETOX, Faculty Faculty of Science, of Science, Masaryk Masa University,ryk University, Kamenice Kamenice 5, 5, 625 00 Brno,Brno, Czech Czech Republic Republic * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.A.); [email protected] (P.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.A.); [email protected] (P.K.) It is our great pleasure to introduce the Festschrift of Chemistry to honor professor JosefIt Michl is our (Figure great pleasure 1) on the to o introduceccasion of the hisFestschrift 80th birthdayof Chemistry and toto recognize honor professor his exceptional Josefcontributions Michl (Figure to 1the) on fields the occasion of organic of his photoc 80th birthdayhemistry, and quantum to recognize chemis his exceptionaltry, biradicals and contributionsbiradicaloids, to electronic the fields of and organic vibrational photochemistry, spectroscopy, quantum magnetic chemistry, circular biradicals dichroism, and sili- biradicaloids,con and boron electronic chemistry, and vibrational supramolecular spectroscopy, chem magneticistry, singlet circular fission, dichroism, and molecular silicon ma- andchines. boron chemistry, supramolecular chemistry, singlet fission, and molecular machines. -

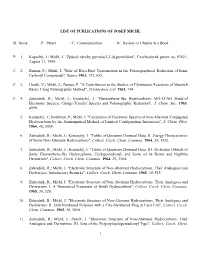

LIST of PUBLICATIONS of JOSEF MICHL B: Book P: Patent C

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS OF JOSEF MICHL B: Book P: Patent C: Communication R: Review or Chapter in a Book P 1. Kopecký, J.; Michl, J. "Zpùsob výroby pyrrolo(2,3-d)-pyrimidinù", Czechoslovak patent no. 97821, August 11, 1959. C 2. Zuman, P.; Michl, J. "Role of Keto-Enol Tautomerism in the Polarographical Reduction of Some Carbonyl Compounds", Nature 1961, 192, 655. C 3. Horák, V.; Michl, J.; Zuman, P. "A Contribution to the Studies of Elimination Reactions of Mannich Bases, Using Polarographic Method", Tetrahedron Lett. 1961, 744. C 4. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J.; Koutecký, J. "Fluoranthene-like Hydrocarbons: MO-LCAO Study of Electronic Spectra, Charge-Transfer Spectra and Polarographic Reduction", J. Chem. Soc. 1963, 4998. 5. Koutecký, J.; Hochman, P.; Michl, J. "Calculation of Electronic Spectra of Non-Alternant Conjugated Hydrocarbons by the Semiempirical Method of Limited Configuration Interaction", J. Chem. Phys. 1964, 40, 2439. 6. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J.; Koutecký, J. "Tables of Quantum Chemical Data. II. Energy Characteristics of Some Non-Alternant Hydrocarbons", Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1964, 29, 1932. 7. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J.; Koutecký, J. "Tables of Quantum Chemical Data. III. Molecular Orbitals of Some Fluoranthene-like Hydrocarbons, Cyclopentadienyl, and Some of its Benzo and Naphtho Derivatives", Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1964, 29, 3184. 8. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J. "Electronic Structure of Non-Alternant Hydrocarbons, Their Analogues and Derivatives. Introductory Remarks", Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1965, 30, 515. 9. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J. "Electronic Structure of Non-Alternant Hydrocarbons, Their Analogues and Derivatives. I. A Theoretical Treatment of Reid's Hydrocarbons", Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. -

Obituary: Rudolf Zahradník Rudolf Zahradník Was Born in 1928 to A

Obituary: Rudolf Zahradník Rudolf Zahradník was born in 1928 to a Czech family in Slovakia. On the eve of the second world war, the family moved to Prague. It was during participation in the Prague uprising in May of 1945 that he met the love of his life, the slightly younger Milena. They were married in 1954 and lived in Prague until the fall of 2020, when they passed away within a week of each other, leaving a daughter and a grandson. Rudolf completed his undergraduate education at the Institute of Chemical Technology in Prague in 1952. This was a time of massive political oppression and he was prevented from entering the graduate program in chemistry. He was fortunate in that an enlightened and courageous director of a Research Institute for Work Hygiene and Occupational Diseases, Prof. J. Teisinger, offered him a refuge. There, Rudolf was in essence his own Ph.D. research supervisor and completed his dissertation in 1956. His work laid the foundations of the QSAR (Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships) method for computer-aided drug design, simultaneously with and independently of C. Hansch at Pomona College in California. The procedure turned out to be very useful and became very popular throughout the world. However, Rudolf soon found the purely empirical nature of QSAR unsatisfactory, and turned his attention to quantum chemistry, which offers truly fundamental insight into chemical processes. He was able to secure a position in one of the institutes of the Academy of Sciences, directed by a leading Czech physical chemist at the time, Prof. R. -

![Self-Assembled Monolayers of Parent and Derivatized [N]Staffane-3,3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6577/self-assembled-monolayers-of-parent-and-derivatized-n-staffane-3-3-2966577.webp)

Self-Assembled Monolayers of Parent and Derivatized [N]Staffane-3,3

J. Am. Chem. SOC.1992,114, 9943-9952 9943 Swedish Board for Technical Development (NUTEK) and Medivir (EMBO) through a 2-year EMBO fellowship to L.H.K. is AB, Lunastigen 7, S-141 44 Huddinge, Sweden, for generous gratefully acknowledged. financial support (to J.C.). Thanks are due to the Wallen- bergstiftelsen, ForskningsrAdsnPmnden, and University of Uppla Supplementary Material Available: Experimental details and for funds for the purchase of a 500-MHz Bruker AMX NMR tables of atomic coordinates, positional atomic coordinates, thermal spectrometer in J.C.'s lab. The Science and Engineering Research parameters, bond distances, bond angles, torsion angles, inter- Council and the Wellcome Foundation Ltd. are gratefully ac- molecular contacts, least-squares planes, and intensity data (24 knowledged for generous financial support (to R.T.W.). Financial pages); listing of structure factors (8 pages). Ordering information Support from the European Molecular Biology Organization is given on any current masthead page. Self-Assembled Monolayers of Parent and Derivatized [ n]Staffane-3,3("-' )-dithiols on Polycrystalline Gold Electrodes Yaw S. Obeng,+Mark E. Laing,' Andrienne C. Friedli, Huey C. Yang, Dongni Wang,f Erik W. Thulstrup,"Allen J. Bard,* and Josef Michl**l Contribution from the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 7871 2-1 167. Received April 2, I992 Abstract: Synthesis of the terminally disubstituted rigid rod molecules, [n]staffane-3,3("')-dithiols, n = 1-4, and their singly functionalized derivatives carrying an acetyl or a pentaammineruthenium(II), [Ru(NH~)~]~+,substituent is described. Self-assembled monolayers of the neat [nlstaffane derivatives and of their mixtures with n-alkyl thiols were prepared on polycrystalline gold electrodes. -

REGIONAL CENTRE of ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES and MATERIALS 2010-2013 Research · Innovation · Education REGIONAL CENTRE of ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES and MATERIALS

REGIONAL CENTRE OF ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES AND MATERIALS 2010-2013 research · innovation · education REGIONAL CENTRE OF ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES AND MATERIALS Šlechtitelů 11, 783 71 Olomouc, Czech Republic +420 585 634 973 http://www.rcptm.com [email protected] Centre Management Prof. RNDr. Radek Zbořil, Ph.D. - General Director Assoc. Prof. RNDr. Ondřej Haderka, Ph.D. - Scientific Director Prof. Ing. Pavel Hobza, Dr.Sc., FRSC, dr.h.c. - Foreign Collaboration Coordinator Mgr. Dalibor Jančík, Ph.D. - Project Manager Mgr. Pavel Tuček, Ph.D. - Grant Policy and Promotions Coordinator Managing Board Prof. RNDr. Miroslav Mašláň, CSc., Palacký University, Olomouc Ing. Antonín Mlčoch, CSc., Palacký University, Olomouc Ing. Radim Ledl, LAC, s.r.o. Assoc. Prof. Jan Řídký, Dr.Sc., ASCR v. v. i., Institute of Physics Ing. Jiřina Shrbená, Inova Pro, s.r.o. Prof. RNDr. Juraj Ševčík, Ph.D., Palacký University, Olomouc Prof. RNDr. Jitka Ulrichová, CSc., Palacký University, Olomouc Administrative Support Mgr. Petra Jungová - Head, Public Tender Department Mgr. Gabriela Rozehnalová - Head, Legal Department Ing. Jana Zimová - Construction Coordinator Ing. Hana Krejčiříková - RCPTM Accountant Mgr. Veronika Poláková - HR Assistant Alena Hynková, Ing. Monika Macharáčková, Mgr. Lucie Mohelníková, Mgr. Miroslava Plaštiaková, Mgr. Jan Klapal published by: Regional Centre of Advanced Technologies and Materials, 2013 graphics: Ing. arch. Linda Pišová, Mgr. Ondřej Růžička; photo: Viktor Čáp RCPTM 1 2 Introductory Message from the Director RCPTM IN BRIEF 6 RCPTM Research Groups -

Cfaed Seminar Series DATE: TIME: LOC: GUEST SPEAKER: Friday

cfaed Seminar Series DATE: Friday, August 12th 2016 TIME: 10:00 am – 11:30 am LOC: CHE91 Chemie-Neubau Bergstraße 66, 01069 Dresden GUEST SPEAKER: Prof. Josef Michl University of Colorado Boulder, USA TITLE: “Direct Alkylation of Gold Surfaces with Solutions of Organometallics" ABSTRACT: Upon treatment with dilute solutions of alkylstannanes and other main group organometallics under ambient conditions, alkyl groups longer than methyl are transferred to gold surface and form a disordered self-limiting monolayer. In most but not all cases, the metal is deposited as well, in elemental form or as an oxide. Spectral and other properties of the monolayer as well as the kinetics of its formation will be discussed and a possible mechanism for the surface alkylation proposed. BIOGRAPHY: Professor Josef Michl teaches in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He is a native of Czechoslovakia, studied at the Charles University in Prague with V. Horák and P. Zuman, and the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences with R. Zahradník, and obtained his Ph.D. in 1965. His post-doctoral experience was in chemistry with R.S. Becker at the University of Houston, M.J.S. Dewar at the University of Texas, A.C. Albrecht at Cornell University, and J. Linderberg at Aarhus University, and in physics with F.E. Harris at the University of Utah. He joined the faculty in the Chemistry Department at Utah in 1970 and was chairman of the department in 1979-84. He left Utah in 1986 and after a brief stint as Collie-Welch Regents Chair Professor at the University of Texas at Austin moved to his present position in Boulder. -

1 CURRICULUM VITAE JOSEF MICHL EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND M.S., Charles University, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1961, with Prof. Václav

1 CURRICULUM VITAE JOSEF MICHL EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND M.S., Charles University, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1961, with Prof. Václav Horák and Dr. Petr Zuman Ph.D., Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1965, with Dr. Rudolf Zahradník POSITIONS 1965-66 Post-doctoral with Professor Ralph S. Becker, University of Houston, Houston, Texas 1966-67 Post-doctoral with Professor Michael J. S. Dewar, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 1967-8/68 Research Scientist, Institute of Physical Chemistry, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czechoslovakia 9/68-7/69 Amanuensis (assistant professor) with Professor Jan Linderberg, Department of Chemistry, Aarhus University, Denmark 9/69-6/70 Post-doctoral with Professor Frank E. Harris, Department of Physics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 7/70-7/71 Research Associate Professor, Department of Chemistry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 7/71-6/75 Associate Professor, Department of Chemistry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 7/75-8/86 Professor, Department of Chemistry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 10/79-6/84 Chairman, Department of Chemistry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 8/86-present Adjunct Professor, Department of Chemistry, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 9/86-5/91 M. K. Collie-Welch Regents Chair in Chemistry, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 6/91-present Professor, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 1/06 - present Group leader, Institute of Organic Chemistry -

Zahradník Lectures 3.Cdr

RUDOLF ZAHRADNÍK LECTURE SERIES “Rudolf Zahradník Lecture Series” is a honorary lecture series under the auspices of the General Director of RCPTM - Prof. Radek Zbořil, established in 2013. All speakers are honored by the medal of the Palacký University for substantial contribution to the particular field of research. First year speakers of the prestigious lecture series were Prof. Josef Michl (University of Colorado and IOCB AS CR, Editor of Chemical Reviews), Prof. Andrey L. Rogach (City University of Hong Kong, Associate Editor of ACS NANO Journal), Prof. Mark A. Ratner (Northwestern University, Feynman Award in Nanotechnology). List of confirmed speakers for the first half of year 2014: Prof. Wolfgang Lindner (University of Vienna). Friday, February 14, 2014, 11:00 Title: „Chromatographic Resolution of Enantiomers on ChiralIon Exchanger: Conceptional Reflections” Wolfgang Lindner was trained in Organic Chemistry receiving his PhD in Graz in 1972. In 1978 he underwent a postdoc stay at the Prof. Barry L. Karger's labs at the North Eastern University in Boston (USA). In 1986 he was a visiting scientist at the FDA/NIH in Bethesda (USA). He has published more than 430 scientific papers, including Chemical Reviews, the Journal of the American Chemical Society or Angewandte Chemie (~10.500 citations, H-50), 12 book articles, and he holds 15 patents. He has received a number of awards including the Chirality Medal, the ACS Award for Chromatography, the AGP Martin Medal, etc. He was appointed the Chair of Analytical Chemistry at the University of Vienna in 1996. His research interests are influenced by pharmaceutical (life) sciences and by separation sciences related to HPLC, GC, CE/CEC and MS. -

Sixty Years of the J. Heyrovský Institute of Physical Chemistry, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Prague (1953 – 2013)

SIXTY YEARS OF THE J. HEYROVSKÝ INSTITUTE OF PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY, ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE CZECH REPUBLIC, PRAGUE (1953 – 2013) Zdenek Herman, Slavoj Černý J. Heyrovský Institute of Physical Chemistry, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Dolejškova 3, 182 23 Prague 8 2. Beginnings 1. Introduction The doctoral students of Professor Jaroslav Heyrovský The present J. Heyrovský Institute of Physical and Professor Rudolf Brdička, mainly physical Chemistry was founded with the formation of the chemists from the polarographic school of Professor Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in 1952 as the Heyrovsky, were responsible for the main research at Laboratory of Physical Chemistry. It started to operate the original Laboratory. on 1st January, 1953. Its first Director was Professor However, the Laboratory’s main task was to Rudolf Brdička (1906-1970], a member of the develop new areas of physical chemistry: Vladimír Academy and professor at Charles University. The Laboratory grew rapidly; in 1955 it became the Institute Fig. 2: The building in 7, Máchova Street of Physical Chemistry. The original locations of the Institute were rooms at the Chemical Institute of Charles University, at its Albertov center. In 1957 the Institute moved to a former state office building on Máchova Street in Vinohrady. After the death of Professor Brdička, the Institute merged with the Institute of Polarography of the Academy of Science in 1972. The J. Heyrovský Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry was formed, with Professor Antonin A. Vlček (1927-1999) as Director. At that time the Institute consisted of laboratories of different sizes scattered all over Prague. The main center of the former Institute of Physical Chemistry was in Máchova Street with about 100 researchers. -

Year-Book 2002, Chemistry

Chemistry Year – Book 2002 Faculty of Science Masaryk University Brno Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic, 2002 Section Chemistry Chemistry Section is a unit of the Faculty of Science housed in three buildings at Kotlarska street and partly also outside at Kamenice street. Encompassing about one hundred academic staff, it offers a quality chemical education in bachelor’s program of chemistry, biochemistry and bachelor’s program for students of applied biochemistry. Besides graduate programme leading to a master degree in several areas of specialisation (analytical chemistry, biochemistry, environmental chemistry, inorganic chemistry, macromolecular chemistry, organic chemistry and physical chemistry) is available. In the same time bachelor’s program for teachers education as well as master degree program for them is offered. Graduate students may enter into the respective Ph.D. programmes. Teaching activities are supported by a necessary research environment. A broad spectrum of modern chemical instruments enables thorough studies on chemical synthesis, molecular structure determination, trace element analysis and kinetics and mechanisms of chemical and biochemical processes, just to mention a few. There exists a significant cooperation with many universities and research institutes in Western Europe and U.S.A. ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE CHEMISTRY SECTION: The Office Head Milan Potáček (Prof., RNDr., CSc.) Deputy Head Zdeněk Glatz (Associate Prof., RNDr., CSc.) Secretary Milena Urbánková The Departments Analytical Chemistry Biochemistry -

Print Special Issue Flyer

an Open Access Journal by MDPI A Special Issue in Honor of Professor Josef Michl Guest Editors: Message from the Guest Editors Prof. Dr. Igor Alabugin This Special Issue is dedicated to Professor Josef Michl, a Department of Chemistry and pioneer in several theoretical and experimental fields of Biochemistry, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA chemistry. Aer obtaining a Ph.D. degree at Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czechoslovakia, in 1965 and [email protected] working as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Prof. Dr. Petr Klán Houston and the University of Texas at Austin, he was Department of Chemistry and associated with several institutions, including the Aarhus RECETOX, Faculty of Science, University, the University of Utah, and the University of Masaryk University, Kamenice 5, Brno, Czech Republic Texas at Austin. Currently, he works at the University of Colorado Boulder, USA, and the Institute of Organic [email protected] Chemistry and Biochemistry at the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic. He has made significant contributions to many fields of theoretical and Deadline for manuscript experimental organic chemistry, such as organic submissions: photochemistry, chemistry of biradicals and biradicaloids, closed (31 December 2020) electronic and vibrational spectroscopy, silicon and boron chemistry, reactive intermediates, and magnetic circular dichroism. This Special Issue will have a broad focus on mechanistic aspects of organic/inorganic chemistry. All submissions will be published free of charge. mdpi.com/si/40857 SpeciaIslsue an Open Access Journal by MDPI Editor-in-Chief Message from the Editor-in-Chief Prof. Dr. Edwin Charles Chemistry is a broad science and in Chemistry we hope to Constable showcase the excellence of this fundamental discipline.