Occupational Health Hazards: Employer, Employee, and Labour Union Concerns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rational Use of Personal Protective Equipment for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and Considerations During Severe Shortages Interim Guidance 6 April 2020

Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages Interim guidance 6 April 2020 Background • avoiding touching your eyes, nose, and mouth; • practicing respiratory hygiene by coughing or This document summarizes WHO’s recommendations for the sneezing into a bent elbow or tissue and then rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in health immediately disposing of the tissue; care and home care settings, as well as during the handling of • wearing a medical mask if you have respiratory cargo; it also assesses the current disruption of the global symptoms and performing hand hygiene after supply chain and considerations for decision making during disposing of the mask; severe shortages of PPE. • routine cleaning and disinfection of environmental and other frequently touched surfaces. This document does not include recommendations for members of the general community. See here: for more In health care settings, the main infection prevention and information about WHO advice of use of masks in the general control (IPC) strategies to prevent or limit COVID-19 community. transmission include the following:2 In this context, PPE includes gloves, medical/surgical face 1. ensuring triage, early recognition, and source control masks - hereafter referred as “medical masks”, goggles, face (isolating suspected and confirmed COVID-19 shield, and gowns, as well as items for specific procedures- patients); 3 filtering facepiece respirators (i.e. N95 or FFP2 or 2. applying standard precautions for all patients and FFP3 standard or equivalent) - hereafter referred to as including diligent hand hygiene; “respirators" - and aprons. This document is intended for 3. -

CONFINED SPACE ENTRY PROGRAM University of Wisconsin-Superior Revised June 2014

University of Wisconsin - Superior Confined Space Program Revised June, 2014 CONFINED SPACE ENTRY PROGRAM University of Wisconsin-Superior Revised June 2014 Section 1 INTRODUCTION A confined space is, by definition, a space that is large enough and so configured that an employee can enter and perform work, has a limited or restricted means for entry or exit and is not intended for continuous human occupancy. Examples of confined spaces include boilers, hoppers, underground vaults, tanks, sewers, storage bins, crawl spaces, pits, ducts, tunnels, diked areas, vessels, and silos. The entry procedures to be used to enter a confined space are determined based on the space classification as either a non-permit or permit-required confined space. A non-permit confined space is a confined space has a safe atmosphere to work in and no other hazards capable of causing death or serious physical harm. A permit-required confined space is a confined space with existing or potential hazards that significantly increase the risk to the employee. These hazards include hazardous atmospheres, electrical hazards, unguarded moving parts, a severely restricted exit from the space, engulfment hazards, converging walls, sloping floors, falls from heights exceeding 6 feet, or any other recognized serious safety or health hazard. Often, work like welding or painting within a non- permit confined space, might introduce significant hazards, and the normal classification of the space would be upgraded to a permit-confined space. The general entry procedure involves a team of individuals, including the employee’s supervisor, the entrant, an attendant and entry supervisor. The classification of the space as a permit or non- permit space determines what steps and personnel are needed to make the entry. -

Occupational Hygiene Report Writing

BACK TO BASICS PEER REVIEWED Occupational hygiene report writing Peter-John “Jakes” ABSTRACT Jacobs Occupational hygiene reports record occupational hygiene exposure assessments. Although their (MPH Occ. Hygiene) Cas Badenhorst (PhD purpose and format can vary, they must provide adequate information for managing occupational Occ. Hygiene) risks and so ensure the health and safety of employees. This article describes how to write a good occupational hygiene report, specifi cally with respect to the minimum content and style. Corresponding author: E-mail: jakes.jacobs2@ Key words: occupational hygiene report, content, standards sasol.com INTRODUCTION When the target audience is the senior management of an The fi ndings of occupational hygiene exposure assessments organisation, the report needs to be concise and prefer- are recorded in occupational hygiene reports. The purpose ably no longer than one page with the technical and other of these reports can vary, for example providing commu- information contained in an appendix. A popularly recounted nication to management, employees, health and safety anecdote is that the average reading ability of a company’s representatives, engineers, etc. regarding occupational chief executive offi cer is equitable to that of a 14-year-old, the hazards present in the workplace, addressing emergencies reason being that they are burdened with massive amounts and, importantly, provide practical exposure control advice of data that must be digested on a daily basis. This report and, are critical in managing occupational risks.1 Although can typically be a summary of fi ndings as described in the several formats for the reports exist, they should all serve detailed occupational hygiene report. -

Natural Disasters: Acts of God, Nature Or Society? on the Social Relation to Natural Hazards J. Weichselgartner & J. Bertens

Risk Analysis II, C.A. Brebbia (Editor) © 2000 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISBN 1-85312-830-9 Natural disasters: acts of God, nature or society? On the social relation to natural hazards J. Weichselgartner & J. Bertens Abstract Natural disasters are characterised by complex relationships and interactions between physical hazards and society. These, as well as local context, cultural aspects, social and political activities, and economic concerns, present diffi- culties in practical application of mitigation concepts and models. This paper outlines general approaches in natural risk assessment and gives an insight into the contextual dynamics surrounding a hazard event. Since precise measurement of uncertainties and exact prediction of damages is hardly feasible, the incorporation of a hazard of place concept in vulnerability assessment is proposed. Qualities that determine potential damage are identified and characteristics described. It is suggested that, even without assessing risk exactly, vulnerability reduction decreases damages and losses. The chosen perspective illustrates that natural disasters are a result of social decision processes rather than acts of God or nature. Introduction We begin our discussion with the words of David Okrent - professor of engineering and applied science at the University of California - to introduce central conceptions in risk assessment. His comment on societal risk is based on testimony he presented on 25 July 1979 to the Subcommittee on Science, Research, and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives, thus four months after Three Mile Island accident: Risk Analysis II, C.A. Brebbia (Editor) © 2000 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISBN 1-85312-830-9 Risk Analysis II "The terms Tiazard' and 'risk' can be used in various ways. -

Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments

Criteria for a Recommended Standard Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Cover photo by Thinkstock© Criteria for a Recommended Standard Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments Revised Criteria 2016 Brenda Jacklitsch, MS; W. Jon Williams, PhD; Kristin Musolin, DO, MS; Aitor Coca, PhD; Jung-Hyun Kim, PhD; Nina Turner, PhD DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. Disclaimer Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations of websites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these websites. Ordering Information This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. To receive NIOSH documents or other information about occupational safety and health topics, contact NIOSH at Telephone: 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636) TTY: 1-888-232-6348 E-mail: [email protected] or visit the NIOSH website at www.cdc.gov/niosh. For a monthly update on news at NIOSH, subscribe to NIOSH eNews by visiting www.cdc.gov/ niosh/eNews. Suggested Citation NIOSH [2016]. NIOSH criteria for a recommended standard: occupational exposure to heat and hot environments. By Jacklitsch B, Williams WJ, Musolin K, Coca A, Kim J-H, Turner N. -

Guide to OH&S Certifications & Designations

THIRD EDITION Guide to OH&S Certifications & Designations A Resource for Safety Practitioners, Employers, and those considering a Career in Occupational Health & Safety COHSPRAC CRST This guide is produced by the Canadian Society of Safety Engineering CSSE Guide to OH&S Certifications & Designations 1 A Guide for Employers and OH&S Practitioners This document has been prepared by Canadian Society of Safety Engineering (CSSE) in the pursuit of CSSE’s mission, vision and goals. All rights reserved. Permission to photocopy or download for individual use is granted. Further reproduction in any manner, including posting to a website, is prohibited without prior written permission of the publisher. Permission may be obtained by contacting the CSSE at [email protected]. © Canadian Society of Safety Engineering 468 Queen Street East, Suite LL-02 Toronto, Ontario M5A 1T7 Tel.: 416-646-1600 www.csse.org Third Edition September 2018 CSSE Guide to OH&S Certifications & Designations 2 A Guide for Employers and OH&S Practitioners PURPOSE OF THE GUIDE The Guide is intended to serve as a resource to employers when hiring a health and safety practitioner. It also provides guidance to future OH&S practitioners on the type of education, experience, and other qualifications being sought by employers. Information on both Canadian and International safety certifications and designations is provided, along with suggested competencies and qualifications for OH&S positions from entry to executive level. An interview guide is included to provide employers with suggested -

Management of Occupational Exposure Limits: a Guide for Mine Ventilation Engineers

Management of Occupational Exposure Limits: A Guide for Mine Ventilation Engineers Derrick J. (Rick) Brake1,2(&) 1 Mine Ventilation Australia, Brisbane, QLD, Australia [email protected] 2 Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Abstract. Many underground mines do not have a qualified or dedicated occupational (industrial) hygienist on site, or even available as a resource. Many mine ventilation engineers do not even consider occupational exposure moni- toring to be relevant to their role as an engineer. In many cases where occu- pational exposure monitoring is conducted, the mine ventilation engineer is not informed about the results of the monitoring, or if he is, cannot interpret cor- rectly what these results mean. This bunker mentality separating occupational hygiene and ventilation engineering reduces the range of tools available to the ventilation engineer to actively adjust or tune the ventilation system to keep the underground environment healthy, or as healthy as it could otherwise be. This paper sets out the principles and practices that the mine ventilation engineer needs to know to be able to understand how to interpret occupational hygiene monitoring results, and the implications for the mine primary and secondary ventilation systems. Keywords: Occupational Á Industrial Á Hygiene Á Monitoring Underground Á Ventilation 1 Introduction In most countries, occupational (or industrial) hygiene is managed by professional hygienists—quite a different field of specialty to engineers; mine ventilation engineers have only been peripherally involved if at all. The exception is probably South Africa where the role of ventilation engineers now tends to encompass at least basic occu- pational hygiene management. There are arguments for and against combining the roles of hygienist and engineer, but the dual-role system has not been adopted elsewhere to date. -

Frequently Asked Question

National Health and Safety Function, Workplace Health and Wellbeing Unit, National HR Division Frequently Asked Question Ref: FAQ 012:02 RE: Chemical Safety Issue date: July 2015 Revised December 2019 Review December 2021 Date: date: Author(s): NH&SF-Information & Advisory Team Note: This information/advice has been issued in response to frequently asked questions around a specific topic and may not cover all issues arising, should you require more specific advice please contact the Health & Safety Help Desk. The management of any occupational safety and health issue(s) remains the responsibility of local management. What is a Chemical Agent /Hazardous Substance? A hazardous substance is something that has the potential to cause harm. The hazards of a substance are evaluated by examining the properties of the substance such as toxicity, flammability and chemical reactivity, as well as how the material is used. What harm can chemicals cause? Chemicals may cause health effects, for example be a respiratory sensitiser or skin irritant Chemicals may be a physical hazard, for example a flammable, explosive or oxidising chemical Chemicals may affect the environment, if they are used, stored or disposed of incorrectly What are the main routes of exposure? Healthcare workers may suffer health effects when hazardous chemicals enter the body. The main routes of exposure are: Inhalation: breathing in the chemical Absorption: through skin contact or a splash in the eye Ingestion: via contaminated food or hands and Inoculation: when a sharp object such as a needle punctures the skin Does the Manager have to complete a risk assessment? Yes, the Safety, Health and Welfare at Work (Chemical Agents) Regulations, 2001 places a duty on the employer to determine whether any hazardous chemical agents are present at the workplace and to assess any risk to the safety and health of employees arising from the presence of those chemical agents. -

Part 18 Personal Protective Equipment Highlights

Occupational Health and Safety Code 2009 Part 18 Explanation Guide Part 18 Personal Protective Equipment Highlights • Section 229 recognizes that the face piece of a full face piece respirator can provide eye protection. • Section 232 requires workers to wear flame resistant outerwear if they could be exposed to a flash fire or electrical equipment flashover. • Section 233 provides several options in protective footwear. Footwear requirements are based on the hazards feet may be exposed to. External safety toecaps are permitted as an alternative to protective footwear when a medical condition prevents a worker from wearing normal protective footwear. Footwear approved to ASTM Standard F2413 is now acceptable for use in Alberta. • Section 234 recognizes both Canadian Standards Association (CSA) and American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standards for protective headwear. • Section 235 requires employers to ensure that a worker riding a bicycle or using in-line skates or a similar means of transport wears an approved cycling helmet. • Section 246 requires employers to ensure that respiratory protective equipment must be approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) or by another organization that sets standards and tests equipment, and is approved by a Director of Occupational Hygiene. Directors of occupational hygiene are staff members of Alberta Human Resources and Employment appointed by the Minister under Section 5 of the OHS Act. • Section 247 requires that employers select respiratory protective equipment in accordance with CSA Standard Z94.4-02, Selection, Use and Care of Respirators. • Section 250 requires that employers test respiratory protective equipment for fit, according to CSA Standard Z94.4-02, Selection, Use and Care of Respirators, or a method approved by a Director of Occupational Hygiene. -

Hazard Communication and the Globally

HAZARD COMMUNICATION AND THE GLOBALLY HARMONIZED SYSTEM OF CLASSIFICATION AND LABELING OF CHEMICALS HAZARD COMMUNICATION AND THE GLOBALLY HARMONIZED SYSTEM OF CLASSIFICATION AND LABELING OF CHEMICALS Contents Labels & Pictograms OSHA Brief: Hazard Communication Standards: Labels and Pictograms ..........3 OSHA Quick Card: Hazard Communication Standard Pictogram ................... 12 OSHA Quick Card: Hazard Communication Standard Labels ......................... 13 Safety Data Sheets OSHA Quick Card: Hazard Communication Standard Safety Data Sheets ...... 14 OSHA Brief: Hazard Communication Standard: Safety Data Sheets .............. 16 Material Safety Data Sheet: Clorox (old format) .......................................... 23 Safety Data Sheet: OxyChem (new format) ............................................... 24 Safety Data Sheet: Tedia (for Practice Exercise) ......................................... 34 Hazard Communication — SDS Practice Exercises ....................................... 41 HAZARD COMMUNICATION AND THE GLOBALLY HARMONIZED SYSTEM OF CLASSIFICATION AND LABELING OF CHEMICALS 1 2 HAZARD COMMUNICATION AND THE GLOBALLY HARMONIZED SYSTEM OF CLASSIFICATION AND LABELING OF CHEMICALS BRIEF Hazard Communication Standard: Labels and Pictograms OSHA has adopted new hazardous chemical standard also requires the use of a 16-section labeling requirements as a part of its recent safety data sheet format, which provides revision of the Hazard Communication detailed information regarding the chemical. Standard, 29 CFR 1910.1200 (HCS), bringing There is a separate OSHA Brief on SDSs it into alignment with the United Nations’ that provides information on the new SDS Globally Harmonized System of Classification requirements. and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS). These changes will help ensure improved quality and All hazardous chemicals shipped after June 1, consistency in the classification and labeling 2015, must be labeled with specified elements of all chemicals, and will also enhance worker including pictograms, signal words and hazard comprehension. -

Guidelines for Statistical Analysis of Occupational Exposure Data

GUIDELINES FOR STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE DATA FINAL by IT Environmental Programs, Inc. 11499 Chester Road Cincinnati, Ohio 45246-0100 and ICF Kaiser Incorporated 9300 Lee Highway Fairfax, Virginia 22031-1207 Contract No. 68-D2-0064 Work Assignment No. 006 for OFFICE OF POLLUTION PREVENTION AND TOXICS U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY 401 M STREET, S.W. WASHINGTON, D.C. 20460 August 1994 DISCLAIMER This report was developed as an in-house working document and the procedures and methods presented are subject to change. Any policy issues discussed in the document have not been subjected to agency review and do not necessarily reflect official agency policy. Mention of trade names or products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. i CONTENTS FIGURES.......................................................... v TABLES........................................................... vi ACKNOWLEDGMENT................................................vii INTRODUCTION.................................................... 1 A. Types of Occupational Exposure Monitoring Data ...................... 1 B. Types of Occupational Exposure Assessments ........................ 2 C. Variability in Occupational Exposure Data ........................... 3 D. Organization of This Report .................................... 4 STEP 1: IDENTIFY USER NEEDS........................................ 9 STEP 2: COLLECT DATA............................................. 15 A. Obtaining Data From NIOSH ................................... 15 -

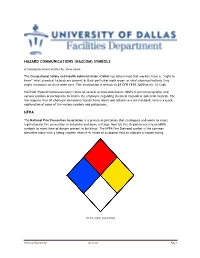

Hazard Communications (Hazcom) Symbols Nfpa

HAZARD COMMUNICATIONS (HAZCOM) SYMBOLS A training document written by: Steve Serna The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has determined that workers have a, “right to know” what chemical hazards are present in their particular work areas, or what chemical hazards they might encounter on their work sites. This information is written in 29 CFR 1910.1200 of the US Code. HAZCOM (Hazard Communications) relies on several written documents (MSDS & written programs) and various symbols or pictograms to inform the employee regarding chemical hazards or potential hazards. The law requires that all chemical containers/vessels have labels and adhere to a set standard; here is a quick explanation of some of the various symbols and pictograms… NFPA The National Fire Prevention Association is a private organization that catalogues and works to enact legislation for fire prevention in industrial and home settings. Most US Fire Departments rely on NFPA symbols to warn them of danger present in buildings. The NFPA Fire Diamond symbol is the common identifier along with a rating number (from 0-4) inside of a colored field to indicate a hazard rating. NFPA FIRE DIAMOND Hazcommadesimple.doc Opr: Serna Page 1 HAZARD RATINGS GUIDE For example: Diesel Fuel has an NFPA hazard rating of 0-2-0. 0 for Health (blue), 2 for Flammability (red), and 0 for Instability/Reactivity (yellow). HMIS (taken from WIKIPEDIA) The Hazardous Materials Identification System (HMIS) is a numerical hazard rating that incorporates the use of labels with color-coded bars as well as training materials. It was developed by the American Paints & Coatings Association as a compliance aid for the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard.