Description: Campina Jay (Cyanocorax Hafferi)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magpie Jay General Information and Care

Magpie Jay General Information and Care: Black Throated Magpie Jays (Calocitta colliei) and White Throated Magpie Jay (Calocitta formosa) are the only two species in their genus. Black Throated Magpie Jays are endemic to Northwestern Mexico. The range of White Throated Magpie Jays lies to the south, overlapping with Black Throats slightly in the Mexican states of Jalisco and Colima, and running into Costa Rica. Both of these birds are members of the family Corvidae. Magpie Jays are energetic, highly intelligent animals and need to be kept in a large planted aviary - not just a cage. These birds are highly social and are commonly found in the wild as cooperative nesters. They are omnivores and favor a great variety of fruits, insects, small rodents, and nuts. A captive diet that works well in my aviaries is a basic pellet low iron softbill diet such as Kaytee’s Exact Original Low Iron Maintenance Formula for Toucans, Mynas and other Softbills. A bowl of this is in the cage at all times and is supplemented with nuts, fruits and veggies like apples, papaya, grapes, oranges, peas and carrots and the occasional treat of small mice and insects like meal worms, crickets, megaworms, and waxworms are relished by the birds. Extra protein is essential if you want these birds to breed. Fresh water should always be provided. I use a shallow three to four inch deep, twelve inch wide crock the birds can drink from and bath in. The birds you are receiving from my aviaries are hand fed and closed banded. How recently they were weaned will affect how tame they are at first. -

S Largest Islands: Scenarios for the Role of Corvid Seed Dispersal

Received: 21 June 2017 | Accepted: 31 October 2017 DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.13041 RESEARCH ARTICLE Oak habitat recovery on California’s largest islands: Scenarios for the role of corvid seed dispersal Mario B. Pesendorfer1,2† | Christopher M. Baker3,4,5† | Martin Stringer6 | Eve McDonald-Madden6 | Michael Bode7 | A. Kathryn McEachern8 | Scott A. Morrison9 | T. Scott Sillett2 1Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA; 2Migratory Bird Center, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC, USA; 3School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia; 4School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 5CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, Ecosciences Precinct, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 6School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 7ARC Centre for Excellence for Coral Reefs Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld, Australia; 8U.S. Geological Survey- Western Ecological Research Center, Channel Islands Field Station, Ventura, CA, USA and 9The Nature Conservancy, San Francisco, CA, USA Correspondence Mario B. Pesendorfer Abstract Email: [email protected] 1. Seed dispersal by birds is central to the passive restoration of many tree communi- Funding information ties. Reintroduction of extinct seed dispersers can therefore restore degraded for- The Nature Conservancy; Smithsonian ests and woodlands. To test this, we constructed a spatially explicit simulation Institution; U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), Grant/Award Number: DEB-1256394; model, parameterized with field data, to consider the effect of different seed dis- Australian Reseach Council; Science and persal scenarios on the extent of oak populations. We applied the model to two Industry Endowment Fund of Australia islands in California’s Channel Islands National Park (USA), one of which has lost a Handling Editor: David Mateos Moreno key seed disperser. -

A Bird in Our Hand: Weighing Uncertainty About the Past Against Uncertainty About the Future in Channel Islands National Park

A Bird in Our Hand: Weighing Uncertainty about the Past against Uncertainty about the Future in Channel Islands National Park Scott A. Morrison Introduction Climate change threatens many species and ecosystems. It also challenges managers of protected areas to adapt traditional approaches for setting conservation goals, and the phil- osophical and policy framework they use to guide management decisions (Cole and Yung 2010). A growing literature discusses methods for structuring management decisions in the face of climate-related uncertainty and risk (e.g., Polasky et al. 2011). It is often unclear, how- ever, when managers should undertake such explicit decision-making processes. Given that not making a decision is actually a decision with potentially important implications, what should trigger management decision-making when threats are foreseeable but not yet mani- fest? Conservation planning for the island scrub-jay (Aphelocoma insularis) may warrant a near-term decision about non-traditional management interventions, and so presents a rare, specific case study in how managers assess uncertainty, risk, and urgency in the context of climate change. The jay is restricted to Santa Cruz Island, one of the five islands within Chan- nel Islands National Park (CINP) off the coast of southern California, USA. The species also once occurred on neighboring islands, though it is not known when or why those populations went extinct. The population currently appears to be stable, but concerns about long-term viability of jays on Santa Cruz Island have raised the question of whether a population of jays should be re-established on one of those neighboring islands, Santa Rosa. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 Version Available for Download From

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 14, 3rd edition). A 4th edition of the Handbook is in preparation and will be available in 2009. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Beatriz de Aquino Ribeiro - Bióloga - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) Designation date Site Reference Number 99136-0940. Antonio Lisboa - Geógrafo - MSc. Biogeografia - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) 99137-1192. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade - ICMBio Rua Alfredo Cruz, 283, Centro, Boa Vista -RR. CEP: 69.301-140 2. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Notices

21262 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Notices acquisition were not included in the 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA Comment (1): We received one calculation for TDC, the TDC limit would not 22041–3803; (703) 358–2376. comment from the Western Energy have exceeded amongst other items. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alliance, which requested that we Contact: Robert E. Mulderig, Deputy include European starling (Sturnus Assistant Secretary, Office of Public Housing What is the purpose of this notice? vulgaris) and house sparrow (Passer Investments, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Department of Housing and Urban The purpose of this notice is to domesticus) on the list of bird species Development, 451 Seventh Street SW, Room provide the public an updated list of not protected by the MBTA. 4130, Washington, DC 20410, telephone (202) ‘‘all nonnative, human-introduced bird Response: The draft list of nonnative, 402–4780. species to which the Migratory Bird human-introduced species was [FR Doc. 2020–08052 Filed 4–15–20; 8:45 am]‘ Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703 et seq.) does restricted to species belonging to biological families of migratory birds BILLING CODE 4210–67–P not apply,’’ as described in the MBTRA of 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of covered under any of the migratory bird the Consolidated Appropriations Act, treaties with Great Britain (for Canada), Mexico, Russia, or Japan. We excluded DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 2005; Pub. L. 108–447). The MBTRA states that ‘‘[a]s necessary, the Secretary species not occurring in biological Fish and Wildlife Service may update and publish the list of families included in the treaties from species exempted from protection of the the draft list. -

The Purplish Jay Rides Wild Ungulates to Pick Food

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305469882 The Purplish Jay rides wild ungulates to pick food Article in Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia · July 2016 CITATIONS READS 0 29 1 author: Ivan Sazima University of Campinas 326 PUBLICATIONS 5,139 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Ivan Sazima letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 05 October 2016 Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 23(4), 365-367 article December 2015 The Purplish Jay rides wild ungulates to pick food Ivan Sazima1 1 Museu de Zoologia, Caixa Postal 6109, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, CEP 13083-970, Campinas, SP, Brazil. 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 15 April 2015. Accepted on 29 December 2015. ABstract: Corvids are renowned for their variable foraging behaviour, and about 20 species in eight genera perch on wild and domestic ungulates to pick ticks on the body of these mammals. Herein I illustrate and briefly comment on the Purplish Jay (Cyanocorax cyanomelas) riding deer and tapir in the Pantanal, Western Brazil. The jay perched on the head or back of the ungulates and searched for ticks, playing the role of a cleaner bird. Deer are rarely reported as hosts or clients of tick-picking birds in the Neotropics. The Purplish Jay is the southernmost Neotropical cleaner corvid reported to date. Given their opportunistic foraging behaviour, a few other Cyanocorax jay species may occasionally play the cleaner role of wild and domestic ungulates. KEY-WORDS: Cyanocorax cyanomelas, foraging, cleaning behaviour, Pantanal, Western Brazil. -

The Puzzling Vocal Repertoire of the South American Collared Jay, Cyanolyca Iridicyana Merida

THE PUZZLING VOCAL REPERTOIRE OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN COLLARED JAY, CYANOLYCA VZRIDZCYANA MERIDA JOHN WILLIAM HARDY Previously, I have indicated (Kansas Sci. Bull., 42: 113, 1961) that the New World jays could be systematically grouped in two tribes on the basis of a variety of morphological and behavioral characteristics. I subsequently demonstrated (Occas. Papers Adams Ctr. Ecol. Studies, No. 11, 1964) the relationships between Cyanolyca and Aphelocoma. The tribe Aphelocomini, comprising the currently recognized genera Aphelocoma and Cyanolyca, may be characterized as follows: pattern and ornamen- tation of head simple, consisting of a dark mask, pale superciliary lineation, and no tendency for a crest; tail plain-tipped; vocal repertoire of one to three basic com- ponents, including alarm calls, flock-social calls, or both, that are nasal, querulous, and upwardly or doubly inflected. In contrast, the Cyanocoracini may be charac- tized as follows: pattern of head complex, consisting of triangular cheek patch, super- ciliary spot, and tendency for a crest; tail usually pale-tipped; vocal repertoire usu- ally complex, commonly including a downwardly inflected cuwing call and never an upwardly inflected, nasal querulous call (when repertoire is limited it almost always includes the cazo!ingcall). None of the four Mexican aphelocomine jays has more than three basic calls in its vocal repertoire. There are two exclusively South American species of CyanuZyca (C. viridicyana and C. pulchra). On the basis of the consistency with which the Mexican and Central American speciesof this genus hew to a general pattern of vocalizations as I described it for the tribe, I inferred (1964 op. -

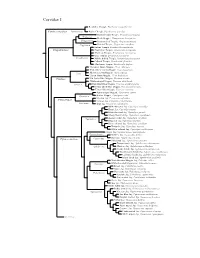

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

The White-Throated Magpie-Jay

THE WHITE-THROATED MAGPIE-JAY BY ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH ORE than 15 years have passed since I was last in the haunts of the M White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa) . During the years when I travelled more widely through Central America I saw much of this bird, and learned enough of its habits to convince me that it would well repay a thorough study. Since it now appears unlikely that I shall make this study myself, I wish to put on record such information as I gleaned, in the hope that these fragmentary notes will stimulate some other bird- watcher to give this jay the attention it deserves. A big, long-tailed bird about 20 inches in length, with blue and white plumage and a high, loosely waving crest of recurved black feathers, the White-throated Magpie-Jay is a handsome species unlikely to be confused with any other member of the family. Its upper parts, including the wings and most of the tail, are blue or blue-gray with a tinge of lavender. The sides of the head and all the under plumage are white, and the outer feathers of the strongly graduated tail are white on the terminal half. A narrow black collar crosses the breast and extends half-way up each side of the neck, between the white and the blue. The stout bill and the legs and feet are black. The sexes are alike in appearance. The species extends from the Mexican states of Colima and Puebla to northwestern Costa Rica. A bird of the drier regions, it is found chiefly along the Pacific coast from Mexico southward as far as the Gulf of Nicoya in Costa Rica. -

Distribution Habitat and Social Organization of the Florida Scrub Jay

DISTRIBUTION, HABITAT, AND SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE FLORIDA SCRUB JAY, WITH A DISCUSSION OF THE EVOLUTION OF COOPERATIVE BREEDING IN NEW WORLD JAYS BY JEFFREY A. COX A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1984 To my wife, Cristy Ann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank, the following people who provided information on the distribution of Florida Scrub Jays or other forms of assistance: K, Alvarez, M. Allen, P. C. Anderson, T. H. Below, C. W. Biggs, B. B. Black, M. C. Bowman, R. J. Brady, D. R. Breininger, G. Bretz, D. Brigham, P. Brodkorb, J. Brooks, M. Brothers, R. Brown, M. R. Browning, S. Burr, B. S. Burton, P. Carrington, K. Cars tens, S. L. Cawley, Mrs. T. S. Christensen, E. S. Clark, J. L. Clutts, A. Conner, W. Courser, J. Cox, R. Crawford, H. Gruickshank, E, Cutlip, J. Cutlip, R. Delotelle, M. DeRonde, C. Dickard, W. and H. Dowling, T. Engstrom, S. B. Fickett, J. W. Fitzpatrick, K. Forrest, D. Freeman, D. D. Fulghura, K. L. Garrett, G. Geanangel, W. George, T. Gilbert, D. Goodwin, J. Greene, S. A. Grimes, W. Hale, F. Hames, J. Hanvey, F. W. Harden, J. W. Hardy, G. B. Hemingway, Jr., 0. Hewitt, B. Humphreys, A. D. Jacobberger, A. F. Johnson, J. B. Johnson, H. W. Kale II, L. Kiff, J. N. Layne, R. Lee, R. Loftin, F. E. Lohrer, J. Loughlin, the late C. R. Mason, J. McKinlay, J. R. Miller, R. R. Miller, B. -

Three Jays Planting on Three Continents

THREE JAYS PLANTING ON THREE CONTINENTS While it is exciting to learn about the different animals, weather and seasons of the other hemisphere, it can also be quite comforting for children to learn of the similarities. When it comes to the raucous, bounding jay, there are many. The Blue Jay of North America (below) is a generic term for at least five species (Cyanocitta), all of which have extensive blue colouring. The Jay of Europe (Garrulus glandarius) , shown below, has just a tiny patch of blue, as if his cousins across the Atlantic had sent him a handkerchief of theirs. The Azure Jay (Cyanocorax caeruleus) of South America's Atlantic Rainforest (below) is like a regal relative with a deep blue cloak and a black hood. All are members of the crow family and it shows in their personalities. All are so well known for their habit of hiding seeds that they have become almost symbolic for it in each region. In late summer and early autumn when seeds from the great trees are falling, the jays on all three continents are greedy about trying to find as many seeds as possible to store. They hide them in logs, under leaves, in the earth, in anticipation of the lean times to come during the winter. Some they find later and eat; some they do not. Those they do not find often germinate and grow into trees. To people observing them, it seems as if they are intentionally planting the seeds and many stories about them doing so are told. In a time when forests are disappearing, reforestation has taken on urgency and almost a sacredness. -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania.