Fcc and Am Stereo: a Deregulatory Breach of Duty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Beatles Albums Identification Guide Updated: 22 De 16

Canadian Beatles Albums Identification Guide Updated: 22 De 16 Type 1 Rainbow Label Capitol Capitol Records of Canada contracted Beatlemania long before their larger and better-known counterpart to the south. Canadian Capitol's superior decision-making brought Beatles records to Canada in early 1963. After experimenting with the release of a few singles, Capitol was eager to release the Beatles' second British album in Canada. Sources differ as to the release date of the LP, but surely by December 2, 1963, Canada's version of With the Beatles became the first North American Beatles album. Capitol-USA and Capitol-Canada were negotiating the consolidation of their releases, but the US release of The Beatles' Second Album had a title and contained songs that were inappropriate for Canadian release. After a third unique Canadian album, album and single releases were unified. From Something New on, releases in the two countries were nearly identical, although Capitol-Canada continued to issue albums in mono only. At the time when Beatlemania With the Beatles came out, most Canadian pop albums were released in the "6000 Series." The label style in 1963 was a rainbow label, similar to the label used in the United States but with print around the rim of the label that read, "Mfd. in Canada by Capitol Records of Canada, Ltd. Registered User. Copyrighted." Those albums which were originally issued on this label style are: Title Catalog Number Beatlemania With the Beatles T-6051 (mono) Twist and Shout T-6054 (mono) Long Tall Sally T-6063 (mono) Something New T-2108 (mono) Beatles' Story TBO-2222 (mono) Beatles '65 T-2228 (mono) Beatles '65 ST-2228 (stereo) Beatles VI (mono) T-2358 Beatles VI (stereo) ST-2358 NOTE: In 1965, shortly before the release of Beatles VI, Capitol-Canada began to release albums in both mono and stereo. -

Owner's Manual

OWNER’S MANUAL M197WD M227WD M237WD Make sure to read the Safety Precautions before using the product. Keep the User's Guide(CD) in an accessible place for furture reference. See the label attached on the product and give the information to your dealer when you ask for service. Trade Mark of the DVB Digital Video Broadcasting Project (1991 to 1996) ID Number(s): 5741 : M227WD 5742 : M197WD 5890 : M237WD PREPARATION FRONT PANEL CONTROLS I This is a simplified representation of the front panel. The image shown may be somewhat different from your set. INPUT INPUT Button MENU MENU Button OK OK Button VOLUME VOL Buttons PROGRAMME PR Buttons Power Button Headphone Button 1 PREPARATION <M197WD/M227WD> BACK PANEL INFORMATION I This is a simplified representation of the back panel. The image shown may be somewhat different from your set. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 COMPONENT AV-IN 3 AUDIO IN IN (RGB/DVI) AV 1 AV 2 OPTICAL Y DIGITAL AV 1 AV 2 AUDIO OUT VIDEO AUDIO 1 B P VIDEO HDMI RGB IN (PC) (MONO) AC IN 2 PR L DVI-D ANTENNA L IN AC IN SERVICE R AUDIO ONLY RS-232C IN (CONTROL & SERVICE) R S-VIDEO 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 1 PCMCIA (Personal Computer Memory Card 7 Audio/Video Input International Association) Card Slot Connect audio/video output from an external device (This feature is not available in all countries.) to these jacks. 2 Power Cord Socket 8 SERVICE ONLY PORT This set operates on AC power. The voltage is indicat- ed on the Specifications page. -

BETS-5 Issue 1 November 1, 1996

BETS-5 Issue 1 November 1, 1996 Spectrum Management Broadcasting Equipment Technical Standard Technical Standards and Requirements for AM Broadcasting Transmitters Aussi disponible en français - NTMR-5 Purpose This document contains the technical standards and requirements for the issuance of a Technical Acceptance Certificate (TAC) for AM broadcasting transmitters. A certificate issued for equipment classified as type approved or as technically acceptable before the coming into force of these technical standards and requirements is considered to be a valid and subsisting TAC. A Technical Acceptance Certificate is not required for equipment manufactured or imported solely for re-export, prototyping, demonstration, exhibition or testing purposes. i Table of Contents Page 1. General ...............................................................1 2. Testing and Labelling ..................................................1 3. Standard Test Conditions ..............................................2 4. Transmitting Equipment Standards .....................................3 5. Equipment Requirements ..............................................4 6. RF Carrier Performance Standards .................................... 5 6.1 Power Output Rating .................................................5 6.2 Modulation Capability ................................................5 6.3 Carrier Frequency Stability ............................................6 6.4 Carrier Level Shift ...................................................7 6.5 Spurious Emissions -

Chapter 4, Current Status, Knowledge Gaps, and Research Needs Pertaining to Firefighter Radio Communication Systems

NIOSH Firefighter Radio Communications CHAPTER IV: STRUCTURE COMMUNICATIONS ISSUES Buildings and other structures pose difficult problems for wireless (radio) communications. Whether communication is via hand-held radio or personal cellular phone, communications to, from, and within structures can degrade depending on a variety of factors. These factors include multipath effects, reflection from coated exterior glass, non-line-of-sight path loss, and signal absorption in the building construction materials, among others. The communications problems may be compounded by lack of a repeater to amplify and retransmit the signal or by poor placement of the repeater. RF propagation in structures can be so poor that there may be areas where the signal is virtually nonexistent, rendering radio communication impossible. Those who design and select firefighter communications systems cannot dictate what building materials or methods are used in structures, but they can conduct research and select the radio system designs and deployments that provide significantly improved radio communications in this extremely difficult environment.4 Communication Problems Inherent in Structures MULTIPATH Multipath fading and noise is a major cause of poor radio performance. Multipath is a phenomenon that results from the fact that a transmitted signal does not arrive at the receiver solely from a single straight line-of-sight path. Because there are obstacles in the path of a transmitted radio signal, the signal may be reflected multiple times and in multiple paths, and arrive at the receiver from various directions along various paths, with various signal strengths per path. In fact, a radio signal received by a firefighter within a building is rarely a signal that traveled directly by line of sight from the transmitter. -

See Cartridge Glossary

32 Cartridge-making Dictionary Audio-Technica’s guide to cartridge-making terminology 33rpm Bonded diamond Channel Balance Connecting (the phono cartridge) very often denotes 12” LP Vinyl records Bonded diamond refers to a The channel balance of a cartridge is the (1949-Today), that should be played at stylus where the diamond tip is ability of the transducer to reproduce left a speed of 33 1/3 rpm, rpm stands for glued on a metal shank that is and right channels in the same manner. Rotation Per Minute. itself glued into the hole of the Channel balance should be part of the cantilever. This construction may cartridge specifications, it expresses the 45rpm increase the mass of the overall tip and possible output difference in dB from one 45rpm very often denotes 7” Vinyl records, affect transient reproduction compared channel to another. A cartridge with ideal (1949-Today) that should be played at a with nude styli that are preferred and used channel balance will playback any mono speed of 45rpm, rpm stands for Rotation on higher-priced models. signal with equal level in both channels. Per Minute. The channel balance will be 0dB. The ratio of the signals between the two channels To install a Phono cartridge, connect the 78rpm Boron (boron cantilever) is specified in dB. Channel imbalance four wires of the cartridge headshell to the 78rpm very often denotes 10” Shellac SP Boron is a chemical element from the can result in several factors independent correct terminals on the back of the Gramophone records (1925-1950) that metalloid family, extracted from Borax and from the cartridge itself: mechanical cartridge. -

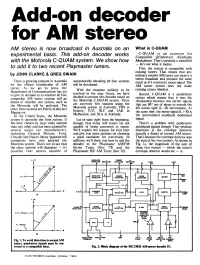

Add-On Decoder for AM Stereo AM Stereo Is Now Broadcast in Australia on an What Is C-QUAM Experimental Basis

Add-on decoder for AM stereo AM stereo is now broadcast in Australia on an What is C-QUAM experimental basis. This add-on decoder works C-QUAM is an acronym for Compatible QUadrature Amplitude with the Motorola C-QUAM system. We show how Modulation. That's certainly a mouthful — let's see what it means. to add it to two recent Playmaster tuners. First, the system is compatible with existing tuners. That means that any by JOHN CLARKE & GREG SWAIN ordinary (mono) AM tuner can receive a stereo broadcast and produce the same There is growing pressure in Australia automatically decoding all four systems result as if it received a mono signal. The for the official introduction of AM will be developed. AM stereo system does not make stereo. As we go to press, the existing tuners obsolete. Department of Communications has yet With the situation unlikely to be to give its decision as to whether all four resolved in the near future, we have Second, C-QUAM is a quadrature decided to present this decoder based on competing AM stereo systems will go system which means that it uses the the Motorola C-QUAM system. There ahead or whether one system, such as relationship between two carrier signals are currently five stations using the the Motorola, will be preferred. The that are 90° out of phase to encode the Motorola system in Australia: 2WS in left minus right (L — R) information. At other three systems are Harris, Kahn and Sydney; 3UZ, 3KZ and 3AK in Magnavox. the same time, the mono signal (L + R) is Melbourne; and 5KA in Adelaide. -

Kosiba Voted Ark Board 25 Per Copy VOL 24 NO 49 the Iuo, THURSDAY MAY 21Rn Flmiuhlihhiiwflihuiiohiíiuiàiniwuui11fflu11n 111M Buy A:

- - -;;T=---?,--------- ********************************************************* ' - . - . ,. , *' MEMORIAL DAY* * Merch*ntsandOrganizatiónal $ponorship Financial Instliution Sponsorship * Pages 22.26 Päges**r*************************************************W**** 16-17 ' Niles and Mill Run come to terms ' Library commends onwheelchair placement Community Outreach program by ElleeisHlrscbfeld , byDlane Miller decisIon last Friday on a legalHerbert, architect designer and ' placement nf wheelchair palrom slorhholdr in Tiffany Produr- Merle Ronenblalt, Nilesdistrict's "communitY outreach" With Nues Village officials meeting of. - breathmg firedown their necks, in the playhouse. -lions -sparred with village of- LibraryDistrictemployee,program at a May 13 Mill Run personnel came to a Representing Mill Ras, Jim toiibiuiedon Page37 reported on the pacress of the ConllnuedonPageti Arnold named Kosiba voted ark Board 25 per copy VOL 24 NO 49 THE iuo, THURSDAY MAY 21rn flmIUhlIHhiiWflIHuiiOhIÍIuIàINIWuUi11fflU11n 111m Buy A: -. iuer.i. S::. ratherthanvote for himself. I..F.am:the -Dan Kosiha sgas reelected to. Kosiba was nominated -for a - his third - term as - Niles Park . third term as president by - - , Board President during Tnesday Beasse. : .. Pop nigkt'nParkBoardmeetiiig-- -- Bud4y PY - Votmg foKnsiba w Pa k Newly elected Commissioner .:BoardCoinminsSnners WalterJim Piershi nominated Beasse . byDavid(Bu d)Bessér - -- : ',.-.Day, .-5O,,,-M,.,-,,00k-,.und -for the presidency and wan the . - -Coi,llnued on Page 38 w renots ewbethe tsanewphmenabtweve -

Vinyl Theory

Vinyl Theory Jeffrey R. Di Leo Copyright © 2020 by Jefrey R. Di Leo Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to publish rich media digital books simultaneously available in print, to be a peer-reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. The complete manuscript of this work was subjected to a partly closed (“single blind”) review process. For more information, please see our Peer Review Commitments and Guidelines at https://www.leverpress.org/peerreview DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11676127 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-015-4 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-016-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019954611 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Without music, life would be an error. —Friedrich Nietzsche The preservation of music in records reminds one of canned food. —Theodor W. Adorno Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments vii Preface 1 1. Late Capitalism on Vinyl 11 2. The Curve of the Needle 37 3. -

REM110 Universal Remote

Thank you for purchasing a Philips Magnavox 3 device univer- sal remote control. This universal remote control will operate your Television,Video Cassette Recorder, and Cable Converter Box. Before you can use your new remote control, you will need to program it to operate the specific components you wish to control. This remote features: • Channel Scan, a convenient way to "channel surf" by scanning channels. • Auto Scan code search to help program remote REM110 control for a variety of components, including Universal Remote older/discontinued models. • Built-in Sleep Timer. • Controls for basic functions, including Power, Channel Selection,Volume, Play and Record. KEYS AND FUNCTIONS 2 1 5 8 3 4 4 7 6 3 9 9 11 10 12 12 13 14 2 1 Red Indicator Light 9 Keypad Replacement and Code Saver The Red Indicator Light blinks Use the keypad (0-9) to to show that the remote con- directly enter in channels (for When the batteries need replacing the remote control will stop work- trol is working and also pro- example, 09 or 31). The key- ing and will require two (2) new "AA" alkaline batteries for continued vides feed back during pro- pad is also used for all pro- operation. Once you remove the old batteries, program settings and gramming sequences. gramming sequences, such as codes will be saved for 10 minutes, allowing adequate time to insert entering in your programming new ones. 2 Component Keys codes. Press TV,VCR or CBL once However, if you do not replace the batteries within the allotted time to select a home entertain- 10 SLEEP Key (e.g., 10 minutes), you will have to reprogram the remote control. -

Digital Radio Strategies in the United States: a Tale of Two Systems

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Faculty Publications 2010 Digital Radio Strategies in the United States: A Tale of Two Systems Alan G. Stavitsky University of Oregon Michael Huntsberger Linfield College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/mscmfac_pubs Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Linfield Citation Stavitsky, Alan G. and Huntsberger, Michael, "Digital Radio Strategies in the United States: A Tale of Two Systems" (2010). Faculty Publications. Accepted Version. Submission 2. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/mscmfac_pubs/2 This Accepted Version is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Accepted Version must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. [1] Chapter Six Digital Radio Strategies in the United States: A Tale of Two Systems Alan G. Stavitsky Michael W. Huntsberger The case of digital radio in North America illuminates the contradiction between federal communication policy ideals and realpolitik . The policy of the United States government gives official imprimatur to robust competition and to local broadcasting that serves ‘the public interest, convenience or necessity,’ in the words of the federal licensing standard (Radio Act of 1927). In the decades since the passage of the Federal Radio Act, notions of capitalism and communication have intertwined as they have been set down in the re- conceptions and revisions of the original statute. -

Inside This Issue

News Serving DX’ers since 1933 Volume 82, No. 17 ● June 22, 2015 ● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 1 … Club Convention 16 … International DX Digest 25 … Geomagnetic Indices 3 … AM Switch 21 … Confirmed DXer 26 … GYDXA 1230 kHz 8 … Domestic DX Digest West 22 … DX Toolbox 31 … GYDXA Updates 12 … Domestic DX Digest East From the Publisher: This is our last issue before the All‐Club DX Convention in Fort Membership Report Wayne July 10‐12. If you haven’t made plans to join us yet, all the information you need starts at “Here are my next year’s dues in the NRC. I the bottom of this page. Hope to see many of you am hoping to be at the convention in Fort Wayne in Fort Wayne! in July, as it will be a great dividing line between Note that new station CJLI‐700 Calgary is now my first fifty years in both NRC and IRCA and on the air 24/7 testing. Station will be REL with my second fifty years in the two clubs.” – Rick slogan “The Light.” Most power goes north, but Evans perhaps we’ll see some loggings of this new New Members – Welcome to Charles Smith, target here in DX News soon. Salem, OR; Michael Vitale, Pinckney, MI; and NRC AM Log Sold Out: The 35th Edition of Gary Whittaker, Albany, NY. Glad to have you the NRC AM Log is now sold out. Wayne has with us! begun working on the 36th Edition and we’ll be Returning Member – And welcome back to updating you on how you can help make the James McGloin, Lockport, IL. -

Prof. K Radhakrishna Rao Lecture 2 Role of Analog Signal Processing

Analog Circuits and Systems Prof. K Radhakrishna Rao Lecture 2 Role of Analog Signal Processing in Electronic Products – Part 1 1 Structure of an electronic product 2 Electronic Products o Process analog signals and digital data o This involve transmission and reception of signals and data o It is generally necessary to code signal and data to transmit over channels o Transmission can be over wires or wireless o Processing and storage are efficient in digital form o Several human interface technologies are available 3 Products considered o Radio Receiver o Modem o Cell Phone o ECG 4 Radio Receiver o AM Receiver o FM Receiver 5 Radio waves are classified as o Low frequency (LF): 30 kHz – 300 kHz, o Medium frequency (MF): 300 kHz – 3 MHz, o High frequency (HF): 3 MHz – 30 MHz, o Very high frequency (VHF): 30 MHz – 300 MHz, o Ultra high frequency (UHF): 300 MHz – 3 GHz, o Super high frequency (SHF): 3 GHz – 30 GHz, o Extremely high frequency (EHF): 30 GHz to 300 GHz. 6 Radio broadcasting o one-way wireless transmission over radio waves to reach a wide audience o takes place in MF (300 kHz – 3 MHz), HF (3 MHz – 30 MHz) and VHF (30 MHz – 300 MHz) regions 7 Major modes of radio broadcasting o Sine wave (single tone) represented by Vtp sin(ωφ+ ) PM (Analog) where φ = phase in radians PSK (Digital) QPSK( Digital) FM (Analog) ω = frequency in rad/sec FSK (Digital) AM, DSB (Analog) V = peak magnitude in volts p ASK (Digital) 8 AM broadcasting o Amplitude of the carrier signal is varied in response to the amplitude of the signal to be transmitted o Amplitude modulation is done by a unit called mixer (nothing but a multiplier) which produces an output output=+( Vpc V pm sinωω m t )sin c t Vpm where ωm is the modulating frequency = m is known as the Vpc ω is the carrier frequency c modulation index.