The Message of Sri Ramakrishna Swami Bhuteshananda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conversations with Swami Turiyananda

CONVERSATIONS WITH SWAMI TURIYANANDA Recorded by Swami Raghavananda and translated by Swami Prabhavananda (This month's reading is from the Jan.-Feb., 1957 issue of Vedanta and the West.) The spiritual talks published below took place at Almora in the Himalayas during the summer of 1915 in the ashrama which Swami Turiyananda had established in cooperation with his brother-disciple, Swami Shivananda. During the course of these conversations, Swami Turiyananda describes the early days at Dakshineswar with his master, Sri Ramakrishna, leaving a fascinating record of the training of an illumined soul by this God-man of India. His memories of life with his brother-disciples at Baranagore, under Swami Vivekananda’s leadership, give a glimpse of the disciplines and struggles that formed the basis of the young Ramakrishna Order. Above all, Swami Turiyananada’s teachings in the pages that follow contain practical counsel on many aspects of religious life of interest to every spiritual seeker. Swami Turiyananda spent most of his life in austere spiritual practices. In 1899, he came to the United States where he taught Vedanta for three years, first in New York, later on the West Coast. By the example of his spirituality he greatly influenced the lives of many spiritual aspirants both in America and India. He was regarded by Sri Ramakrishna as the perfect embodiment of that renunciation which is taught in the Bhagavad Gita Swami Shivananda, some of whose talks are included below, was also a man of the highest spiritual realizations. He later became the second President of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission. -

THE LION of VEDANTA a Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of the Ramakrishna Order Since 1914

nd Price: ` 10 YEAR OF PUBLICATION 㼀㼔㼑㻌㼂㼑㼐㼍㼚㼠㼍㻌㻷㼑㼟㼍㼞㼕 THE LION OF VEDANTA A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 Jagadamba Ashrama, Koalpara, Jayarambati, West Bengal May 2015 2 India's Timeless Wisdom Just as the farmer reaps the fruit according to the seed that he plants in the field, a man reaps spiritual merit or sin according to the acts he performed. —Traditional Saying Editor: SWAMI ATMASHRADDHANANDA Managing Editor: SWAMI GAUTAMANANDA PrintedPri and published by Swami Vimurtananda on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trustst 2 fromThe No.31, RamakrishnaV edanta KMathesari Road, ~ Mylapore, ~ MAY Chennai2015 - 4 and Printed at Sri Ramakrishna Printing Press, No.31 Ramakrishna Math Road, Mylapore, Chennai - 4. Ph: 044 - 24621110 㼀㼔㼑㻌㼂㼑㼐㼍㼚㼠㼍㻌㻷㼑㼟㼍㼞㼕 102nd YEAR OF PUBLICATION VOL. 102, No. 5 ISSN 0042-2983 A CULTURAL AND SPIRITUAL MONTHLY OF THE RAMAKRISHNA ORDER Started at the instance of Swami Vivekananda in 1895 as Brahmavâdin, it assumed the name The Vedanta Kesari in 1914. For free edition on the Web, please visit: www.chennaimath.org CONTENTS MAY 2015 Gita Verse for Reflection 165 Editorial Rowing the Boat of Life 166 Articles Down the Memory Lane—The First Centenary Celebration of Sri Ramakrishna’s Birth 174 Swami Sambuddhananda Transformation of Narendranath into Swami Vivekananda: A Snapshot 179 Asim Chaudhuri Worshipping God through Images: A Hindu Perspective 186 Umesh Gulati The School in Chennai Started by Swami Ramakrishnananda 192 A Monastic Sojourner New Find Unpublished Letters of Swami Saradananda -

Christian and Hindu Swami Ranganathananda Moulding Our

358 MARCH - APRIL 2011 Monastic Spirituality: Christian and Hindu Swami Ranganathananda Moulding Our Lives with Sri Ramakrishna’s Teachings Swami Bhuteshananda Divine Wisdom MASTER: "Once a teacher was explaining to a disciple: God alone, and no one else, is your own.' The disciple said: 'But, revered sir, my mother, my wife, and my other relatives take very good care of me. They see nothing but darkness when I am not present. How much they love me!' The teacher said: 'There you are mistaken. I shall show you presently that nobody is your own. Take these few pills with you. When you go home, swallow them and lie down in bed. People will think you are dead, but you will remain conscious of the outside world and will see and hear everything. Then I shall visit your home. "The disciple followed the instructions. He swallowed the pills and lay as if unconscious in his bed. His mother, wife, and other relatives began to cry. Just then the teacher came in, in the guise of a physician, and asked the cause of their grief. When they had told him everything, he said to them: 'Here is a medicine for him. It will bring him back to life. But I must tell you one thing. This medicine must first be taken by one of his relatives and then given to him. But the relative who takes it first will die. I see his mother, his wife, and others here. Certainly one of you will volunteer to take the medicine. Then the young man will come back to life.' "The disciple heard all this. -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

Was Swami Vivekananda a Hindu Supremacist? Revisiting a Long-Standing Debate

religions Article Was Swami Vivekananda a Hindu Supremacist? Revisiting a Long-Standing Debate Swami Medhananda y Program in Philosophy, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda Educational and Research Institute, West Bengal 711202, India; [email protected] I previously published under the name “Ayon Maharaj”. In February 2020, I was ordained as a sannyasin¯ of y the Ramakrishna Order and received the name “Swami Medhananda”. Received: 13 June 2020; Accepted: 13 July 2020; Published: 17 July 2020 Abstract: In the past several decades, numerous scholars have contended that Swami Vivekananda was a Hindu supremacist in the guise of a liberal preacher of the harmony of all religions. Jyotirmaya Sharma follows their lead in his provocative book, A Restatement of Religion: Swami Vivekananda and the Making of Hindu Nationalism (2013). According to Sharma, Vivekananda was “the father and preceptor of Hindutva,” a Hindu chauvinist who favored the existing caste system, denigrated non-Hindu religions, and deviated from his guru Sri Ramakrishna’s more liberal and egalitarian teachings. This article has two main aims. First, I critically examine the central arguments of Sharma’s book and identify serious weaknesses in his methodology and his specific interpretations of Vivekananda’s work. Second, I try to shed new light on Vivekananda’s views on Hinduism, religious diversity, the caste system, and Ramakrishna by building on the existing scholarship, taking into account various facets of his complex thought, and examining the ways that his views evolved in certain respects. I argue that Vivekananda was not a Hindu supremacist but a cosmopolitan patriot who strove to prepare the spiritual foundations for the Indian freedom movement, scathingly criticized the hereditary caste system, and followed Ramakrishna in championing the pluralist doctrine that various religions are equally capable of leading to salvation. -

Polyclinic News

Volume:-11, No. 5 Dec. 16 to Jan. 17 “They alone live who live for others. The rest are more dead than alive.” Polyclinic News Ramakrishna Mission Sevashrama, Lucknow, runs the Vivekananda Polyclinic & Institute of Medical Sciences, a 350 bedded multi-speciality community hospital with the objective of providing quality healthcare at the lowest cost to all patients and to provide charity services to deserving patients from the lower socio-economic strata. Upgradation of Equipment in Physiotherapy: The Physiotherapy Department of Vivekananda Polyclinic & Institute of Medical Sciences (VPIMS), Lucknow has been continuously upgrading its equipment profile and has procured 02 Multi-channel Microprocessor Based TENS and 02 Hydro collator Machine (8 Packs large size) manufactured by Rapid Electro Med. The machines were inaugurated on 21st December 2017 by Swami Muktinathananda, the Secretary of the Institute. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) are predominately used for nerve related pain conditions (acute and chronic conditions). TENS machines works by sending stimulating pulses across the surface of the skin and along the nerve strands. The stimulating pulses help prevent pain signals from reaching the brain. Tens devices also stimulate the body to produce higher levels of its own natural painkillers, called "Endorphins". It can be used for pain relief in several types of illness and conditions such as Osteoarthritis, acute lumbar and cervical pain, tendinitis and bursitis. Hydro Collator is a stationary or mobile stainless steel thermo statistically controlled water heating device designed to 0 heat silica field packs in water up to 160 C. The packs are removed and wrapped in several layers of towel and applied to the affected part of the body. -

Newsletter Reach Jan 2021

Reach Issue 56 January 2021 Daintree Rainforest Reach https://glampinghub.com/ Newsletter of the Vedanta Centres of Australia Sayings and Teachings IN THIS ISSUE 1. News from Australian Sri Ramakrishna on a True Teacher Centres Adelaide He alone is the true teacher who is illumined by the light of true Brisbane knowledge. Canberra Source: Great Sayings: Words of Sri Ramakrishna, Sarada Devi and Swami Melbourne Vivekananda; The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture; Calcutta; page 9. Perth Sydney Sri Sarada Devi on Herself Obituary: Reflections on the Life of Late Sri Ramakrishna left me behind to manifest the Motherhood of God to the world. Dr. Amrithalingam Source: Great Sayings: Words of Sri Ramakrishna, Sarada Devi and Swami by Swami Sridharananda Vivekananda; The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture; Calcutta; page 20. 2. Feature Article: Shinto Swami Vivekananda on Man Take up one idea. Make that one idea your life —think of it, dream of it, live on that idea. Let the brain, muscles, nerves, every part of your body, be full of that idea, and just leave every other idea alone. This is the way to success. Source: Great Sayings: Words of Sri Ramakrishna, Sarada Devi and Swami Vivekananda; The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture; Calcutta; page 35-36. e welcome you all to the Vedanta Movement in Australia, as epitomized in the lives of Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi and Swami Vivekananda, and invite you to involve yourselves and actively participate in the propagation of W the Universal Message of Vedanta. Issue No. 56 January 2021 Page 1 Reach 1. -

VII. the Swami Swahananda Era (1976-2012)

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present VII. The Swami Swahananda Era (1976-2012) 1. Swami Swahananda’s Background 2. Swami Swahananda’s Major Objectives 3. Swami Swahananda at the Vedanta Society of Southern California 4. The Assistant Swamis 5. Functional Departments of the Vedanta Society 6. Charitable Organizations 7. Santa Barbara Temple and Convent 8. Ramakrishna Monastery, Trabuco Canyon 9. Vivekananda House, South Pasadena (1955-2012) 1. Swami Swahananda’s Background* fter Swami Prabhavananda passed away on July 4, 1976, Swami Chetanananda was assigned the position of head of the A Vedanta Society of Southern California (VSSC). Swamis Vireswarananda and Bhuteshananda, President and Vice- President of the Ramakrishna Order, urged Swami Swahananda to take over the VSSC. They realized that a man with his talents and capabilities should be in charge of a large center. Swahananda agreed to leave the quiet life of Berkeley for the more challenging work in the Southland. Having previously been in charge of the large New Delhi Center in the capital of India, he was up to the task and assumed leadership of the VSSC on December 15, 1976. He was enthusiastically welcomed, and soon became well established in the life of the Society. Swami Swahananda was born on June 29, 1921 in Habiganj, Sylhet in Bengal (now in Bangladesh). His father had been a government official and an initiated disciple of Holy Mother. He had wanted to renounce the world and become a monk, but Holy Mother reportedly had told him, “No, my child, but from your family two shall come.” (As well as Swahananda, a nephew also later joined the Ramakrishna Order). -

2020 2019 2020

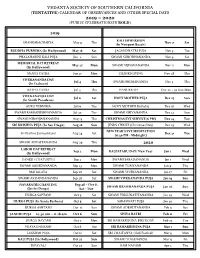

VEDANTA SOCIETY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA (TENTATIVE) CALENDAR OF OBSERVANCES AND OTHER SPECIAL DAYS 2019 – 2020 (PUBLIC CELEBRATIONS IN BOLD) 2019 KALI IMMERSION SHANKARACHARYA May 9 Thu Nov 2 Sat (In Newport Beach) BUDDHA PURNIMA (In Hollywood) May 18 Sat JAGADDHATRI PUJA Nov 5 Tue PHALAHARINI KALI PUJA Jun 2 Sun SWAMI SUBODHANANDA Nov 9 Sat MEMORIAL DAY RETREAT May 27 Mon SWAMI VIJNANANANDA Nov 11 Mon (In Hollywood) SNANA YATRA Jun 17 Mon THANKSGIVING Nov 28 Thu VIVEKANANDA DAY Jul 4 Thu SWAMI PREMANANDA Dec 5 Thu (In Trabuco) RATHA YATRA Jul 4 Thu HANUKKAH Dec 22 – 30 Sun-Mon VIVEKANANDA DAY Jul 6 Sat HOLY MOTHER PUJA Dec 15 Sun (In South Pasadena) GURU PURNIMA Jul 16 Tue HOLY MOTHER Birthday Dec 18 Wed SWAMI RAMAKRISHNANANDA Jul 30 Tue SWAMI SHIVANANDA Dec 22 Sun SWAMI NIRANJANANANDA Aug 15 Thu CHRISTMAS EVE SERVICE(6 PM) Dec 24 Tue SRI KRISHNA PUJA (In San Diego) Aug 18 Sun JESUS CHRIST (Christmas Day) Dec 25 Wed NEW YEAR'S EVE MEDITATION Sri Krishna Janmashtami Aug 24 Sat Dec 31 Tue (11:30 PM - Midnight) SWAMI ADVAITANANDA Aug 29 Thu 2020 LABOR DAY RETREAT Sep 2 Mon KALPATARU DAY/ New Year Jan 1 Wed (In Hollywood) GANESH CHATURTHI Sep 2 Mon SWAMI SARADANANDA Jan 1 Wed SWAMI ABHEDANANDA Sep 23 Mon SWAMI TURIYANANDA Jan 9 Thu MAHALAYA Sep 28 Sat SWAMI VIVEKANANDA Jan 17 Fri SWAMI AKHANDANANDA Sep 28 Sat SWAMI VIVEKANANDA PUJA Jan 19 Sun NAVARATRI CHANTING Sep 28 – Oct 8, SWAMI BRAHMANANDA PUJA Jan 26 Sun (Jai Sri Durga) Sat - Tue DURGA SAPTAMI Oct 5 Sat SWAMI TRIGUNATITANANDA Jan 29 Wed DURGA PUJA (In Santa Barbara) Oct 5 Sat SARASWATI PUJA Jan 30 Thu DURGA ASHTAMI Oct 6 Sun SWAMI ADBHUTANANDA Feb 9 Sun SANDHI PUJA 10.30 am – 11.18 am Oct 6 Sun SHIVA RATRI Feb 21 Fri DURGA NAVAMI Oct 7 Mon SRI RAMAKRISHNA BIRTHDAY Feb 25 Tue VIJAYA DASHAMI Oct 8 Tue SRI RAMAKRISHNA PUJA Mar 1 Sun LAKSHMI PUJA Oct 12 Sat SRI CHAITANYA (Holi Festival) Mar 9 Mon KALI PUJA (In Hollywood) Oct 27 Sun SWAMI YOGANANDA Mar 13 Fri DIPAVALI Oct 27 Sun RAM NAVAMI Apr 2 Thu . -

Shivananda, Yes, the Question Arises and Is Significant Too. It Is Like The

The first thing to understand is that I have no teachings. I am not teaching you anything at all, because teaching simply means conditioning your mind -- in other words, programming you in a certain way. What I am doing here is just the opposite of teaching you: I am creating a space where you can unlearn whatsoever you have been taught up to now. I am not a teacher! That's the difference between a teacher and a Master: the teacher teaches, the Master helps you to undo whatsoever the teachers have done. The function of the Master is just the opposite of that of the teacher. The teacher serves the society, the establishment; he is the agent of the past. He works for the older generation: he tries to condition the minds of the new generation so they can be subservient, obedient to the past, to all that is old -- to their parents, to the society, to the state, to the church. The function of the teacher is anti-revolutionary, it is reactionary The Master is basically a rebel. He is not in the service of the past, he is not an agent of all that you can think of as 'the establishment' -- religious, political, social, economic -- his whole effort is to help you to discover your individuality. It has nothing to do with tradition, convention. You have to go within, not backwards. He is not in any way interested in forcing you into a certain pattern; he makes you free. So what I am doing here is not teaching, that is a misunderstanding on your part. -

The Chronology of Swami Vivekananda in the West

HOW TO USE THE CHRONOLOGY This chronology is a day-by-day record of the life of Swami Viveka- Alphabetical (master list arranged alphabetically) nanda—his activites, as well as the people he met—from July 1893 People of Note (well-known people he came in to December 1900. To find his activities for a certain date, click on contact with) the year in the table of contents and scroll to the month and day. If People by events (arranged by the events they at- you are looking for a person that may have had an association with tended) Swami Vivekananda, section four lists all known contacts. Use the People by vocation (listed by their vocation) search function in the Edit menu to look up a place. Section V: Photographs The online version includes the following sections: Archival photographs of the places where Swami Vivekananda visited. Section l: Source Abbreviations A key to the abbreviations used in the main body of the chronology. Section V|: Bibliography A list of references used to compile this chronol- Section ll: Dates ogy. This is the body of the chronology. For each day, the following infor- mation was recorded: ABOUT THE RESEARCHERS Location (city/state/country) Lodging (where he stayed) This chronological record of Swami Vivekananda Hosts in the West was compiled and edited by Terrance Lectures/Talks/Classes Hohner and Carolyn Kenny (Amala) of the Vedan- Letters written ta Society of Portland. They worked diligently for Special events/persons many years culling the information from various Additional information sources, primarily Marie Louise Burke’s 6-volume Source reference for information set, Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discov- eries. -

The Vedanta Society of St

The Vedanta Society of St. Louis Swami Chetanananda – Minister and Spiritual Teacher RAMAKRISHNA ORDER OF INDIA July-August 2019 Sunday Services 10:30 a.m. July 7 Early Years of St. Louis Vedanta (video) By First Vedanta Students (1939-1957) 14 Reminiscences of Holy Mother and Swami Brahmananda (video) Swami Bhuteshananda 21 Teachings of Ramakrishna Swami Nirakarananda 28 The Message of the Bhagavad Gita (video) Swami Swananda August 4 Reminiscences of Ramakrishna’s Monastic Disciples (video) Swami Bhuteshananda 11 Satsang Swami Nishpapananda and Swami Nirakarananda 18 How to Cope with Dryness in Spiritual Life (video) Swami Prabuddhananda 25 Reminiscences of Swamis Shivananda and Vijnanananda (video) Swami Lokeswarananda Special Event 10:30 a.m. July 4, Thurs. Vivekananda Festival (205 S. Skinker) Chanting, meditation, symposium, music. Lunch 12:45 p.m No Classes Tuesday or Thursday (Summer Break) Membership in the Society is open to all who accept Vedantic teachings. The Society maintains a rental library for members and stocks books for sale. www.vedantastl.org YouTube: VedantaSTL ALL ARE WELCOME More Than Anyone Else Mother always wanted to feed her children with good items. The first devotee to arrive got the best things, the next got the best of what remained during his turn and so on. Every one was happy and felt that Mother ‘loved him more than anyone else.’ The same love and unbounded affection of Mother to every devotee would sometimes reveal a unique experience in their minds. Nalini Babu tells: “I went one day with Shyamdas Goswami of Beldihar to see Mother. The moment we saw her, she said, ‘Oh, how much distance you have walked! How many difficulties you have faced! First, take some water!’ Keeping both of us near her, she fed us with puffed rice and sandesh.