Filmmaking in the Age of Digital Video

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hansard 8 December 2017

2017/18 SESSION of the BERMUDA HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL HANSARD REPORT 8 December 2017 Sitting number 12 of the 2017/18 Session (pages 821–972) Hon. Dennis P. Lister, Jr., JP, MP Speaker Disclaimer: The electronic version of the Official Hansard Report is for informational purposes only. The printed version remains the official record. Official Hansard Report 8 December 2017 821 BERMUDA HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL HANSARD REPORT 8 DECEMBER 2017 10:03 AM Sitting Number 12 of the 2017/18 Session [Hon. Dennis P. Lister, Jr., Speaker, in the Chair] to acknowledge that she is doing well, and we contin- ue to wish her well. PRAYERS Some Hon. Members: Yes. [Prayers read by Mr. Clark Somner, Deputy Clerk] HANDICAPPED PARKING CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES [Minutes of 1 December 2017] The Speaker: Also, during the maiden speech of our Member, Ms. Furbert, last week, she highlighted the challenge that the handicapped community faces in The Speaker: Members, we received the Minutes of the 1st of December. this Island, like elsewhere. And she reminded us that Are there any amendments or corrections, we should respect the needs of the handicapped and adjustments that have to be made? No adjustments, that handicapped parking at these facilities should be no corrections? respected. So, I am asking all Members and staff to The Minutes are confirmed. respect the handicapped parking and realise that it is there for a purpose. And if you do not require or need [Minutes of 1 December 2017 confirmed] it, do not park in it. MESSAGES FROM THE GOVERNOR SELECT COMMITTEES—MEMBERSHIP CHANGES The Speaker: I would also like to announce some The Speaker: There are none. -

^^SOJVIAN 4^ Fc, 3 Smithsonian Center for Folklife Ami Cultural Heritage

^^SOJVIAN 4^ fc, 3 Smithsonian Center for Folklife ami Cultural Heritage 750 9th Street NW Suite 4100 Washington, DC 20560-0953 www.folklife.si.edu « 2001 by the Smithsonian Institution ISSN 1056-6805 EDITOR: Carla M. Borden ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Peter Seitel DIRECTOR OF DESIGN: Kristen Femekes GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Caroline Brownell DESIGN ASSISTANT: Michael Bartek Cover image: Gombeys are the masked dancers of Bermuda. Art from photo courtesy the Bermuda Government . mB^th Annual Smithsonian Folklife Festiva On The National Mall, Washington, D.C. June 27 - July 1 a July 4 - July 8, 2001 Bermuda Connection Mew York City amhe Smithsonian' Masters c#!he Building Arts NewYOiK CITY ax THe smiTHSonian The Festiva. This program is produced in collaboration with Mew York's is co-sponsored by __ Center for Traditional Music and Dance and City Lore, the National Park Service. with major funding from the New York City Council, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, The Festival is supported by federally Howard P. Milstein, and the New York Stock Exchange. appropriated funds, Smithsonian trust funds, The Leadership Committee is co-chaired by The Honorable contributions from governments, businesses, Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Elizabeth Moynihan and foundations, and individuals, in-kind corporate chairman Howard P. Milstein. assistance, volunteers, food and craft sales, and Friends of the Festival. Major support is provided by Amtrak, Con Edison, the Recording Industries Music Performance Trust Funds, IVIajor in-kind support has been provided by Arthur Pacheco, and the Metropolitan Transportation GoPed and IVIotorola/Nextel. Authority. Major contributors include The New York Community Trust, The Coca-Cola Company, The Durst Foundation, the May £t Samuel Rudin Family Foundation, Leonard Litwin, and Bernard Mendik. -

The Eddie Awards Issue

THE MAGAZINE FOR FILM & TELEVISION EDITORS, ASSISTANTS & POST- PRODUCTION PROFESSIONALS THE EDDIE AWARDS ISSUE IN THIS ISSUE Golden Eddie Honoree GUILLERMO DEL TORO Career Achievement Honorees JERROLD L. LUDWIG, ACE and CRAIG MCKAY, ACE PLUS ALL THE WINNERS... FEATURING DUMBO HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON: THE HIDDEN WORLD AND MUCH MORE! US $8.95 / Canada $8.95 QTR 1 / 2019 / VOL 69 Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. -

2020 Sundance Film Festival: 118 Feature Films Announced

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: December 4, 2019 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2020 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL: 118 FEATURE FILMS ANNOUNCED Drawn From a Record High of 15,100 Submissions Across The Program, Including 3,853 Features, Selected Films Represent 27 Countries Once Upon A Time in Venezuela, photo by John Marquez; The Mountains Are a Dream That Call to Me, photo by Jake Magee; Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, courtesy of Sundance Institute; Beast Beast, photo by Kristian Zuniga; I Carry You With Me, photo by Alejandro López; Ema, courtesy of Sundance Institute. Park City, UT — The nonprofit Sundance Institute announced today the showcase of new independent feature films selected across all categories for the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. The Festival hosts screenings in Park City, Salt Lake City and at Sundance Mountain Resort, from January 23–February 2, 2020. The Sundance Film Festival is Sundance Institute’s flagship public program, widely regarded as the largest American independent film festival and attended by more than 120,000 people and 1,300 accredited press, and powered by more than 2,000 volunteers last year. Sundance Institute also presents public programs throughout the year and around the world, including Festivals in Hong Kong and London, an international short film tour, an indigenous shorts program, a free summer screening series in Utah, and more. Alongside these public programs, the majority of the nonprofit Institute's resources support independent artists around the world as they make and develop new work, via Labs, direct grants, fellowships, residencies and other strategic and tactical interventions. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

A Film Music Documentary

VULTURE PROUDLY SUPPORTS DOC NYC 2016 AMERICA’s lARGEST DOCUMENTARY FESTIVAL Welcome 4 Staff & Sponsors 8 Galas 12 Special Events 15 Visionaries Tribute 18 Viewfinders 20 Metropolis 24 American Perspectives 29 International Perspectives 33 True Crime 36 DEVOURING TV AND FILM. Science Nonfiction 38 Art & Design 40 @DOCNYCfest ALL DAY. EVERY DAY. Wild Life 43 Modern Family 44 Behind the Scenes 46 Schedule 51 Jock Docs 55 Fight the Power 58 Sonic Cinema 60 Shorts 63 DOC NYC U 68 Docs Redux 71 Short List 73 DOC NYC Pro 83 Film Index 100 Map, Pass and Ticket Information 102 #DOCNYC WELCOME WELCOME LET THE DOCS BEGIN! DOC NYC, America’s Largest Documentary hoarders and obsessives, among other Festival, has returned with another eight days fascinating subjects. of the newest and best nonfiction programming to entertain, illuminate and provoke audiences Building off our world premiere screening of in the greatest city in the world. Our seventh Making A Murderer last year, we’ve introduced edition features more than 250 films and panels, a new t rue CriMe section. Other fresh presented by over 300 filmmakers and thematic offerings include SceC i N e special guests! NONfiCtiON, engaging looks at the worlds of science and technology, and a rt & T HE C ITY OF N EW Y ORK , profiles of artists. These join popular O FFICE OF THE M AYOR This documentary feast takes place at our Design N EW Y ORK, NY 10007 familiar venues in Greenwich Village and returning sections: animal-focused THEl wi D Chelsea. The IFC Center, the SVA Theatre and life, unconventional MODerN faMilY Cinepolis Chelsea host our film screenings, while portraits, cinephile celebrations Behi ND the sCeNes, sports-themed JCO k DO s, November 10, 2016 Cinepolis Chelsea once again does double duty activism-oriented , music as the home of DOC NYC PrO, our panel f iGht the POwer and masterclass series for professional and doc strand Son iC CiNeMa and doc classic aspiring documentary filmmakers. -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

31. Oktober 1994 COOL POP • POLITICS • HOLLYWOOD 1960-68

Retrospektive GESTE R R EI CHISCHES Viennale 1994 FILMMUSEUM 1.-31. Oktober 1994 COOL POP • POLITICS • HOLLYWOOD 1960-68 MIT FILMEN VON ROBERT ALDRICH WILLIAM ASHER • GEORGE AXELROD ALLEN BARON • JOHN BOORMAN • MARLON B RAN DO RICHARD BROOKS WILLIAM CONRAD • ROGER CORMAN EDWARD DMYTRYK • BLAKE EDWARDS • RICHARD FLEISCHER THEODORE FLICKER ROBERT FLOREY JOHN FORD JOHN FRANKENHEIMER SAMUEL FÜLLER • GUY HAMILTON • HARVEY HART HOWARD HAWKS MONTE HELLMAN DOUGLAS HEYES • ALFRED HITCHCOCK JOHN HUSTON • NORMAN JEWISON ■ ELIA KAZAN • STANLEY KUBRICK • IRVIN LERNER • RICHARD LESTER JERRY LEWIS • SIDNEY LUMET LESLIE MARTINSON RUSS MEYER • JOSEPH M. NEWMAN • SAM PECKINPAH • ARTHUR PENN ■ FRANK PERRY • ROMAN POLANSKI OTTO PREMINGER • ROBERT ROSSEN FRANKLIN J. SCHAFFNER • GEORGE SIDNEY DON SIEGEL • ALEXANDER SINGER • JOHN STURGES PETER USTINOV ROGER VADIM • PAUL WENDKOS BILLY WILDER RON WINSTON Samstag, 1. Oktober 1994, 17.00 Uhr Montag. 3. Oktober 1994, 17.00 Uhr Mittwoch. 5. Oktober 1994. 17.00 Uhr Freitag. 7. Oktober 1994, 17.00 Uhr Sonntag, 9. Oktober 1994, 17.00 Uhr Dienstag, 11. Oktober 1994, 17 00 Uhr Twilight Zone: IN PRAISE OF PIP (1963) FATHOM (1967) THE BELLBOY (1960) Joseph M. Newman SEVEN DAYS IN MAY (1964) ANGEL BABY (1961) FAIL SAFE (1964) Regie: Leslie H. Martinson; Drehbuch: Lorenzo Regie und Drehbuch: Jerry Lewis; Kamera THE KILLERS (1964) Regie: John Frankenheimer; Drehbuch: Rod Ser- Semple, Jr.; Kamera: Douglas Slocombe; Bauten: Regie: Paul Wendkos; Drehbuch: Orin Borsten, Regie: Sidney Lumet; Drehbuch: Walter Bern¬ Haskell Boggs; Bauten: Hai Pereira, Henry ling; Kamera: Ellsworlh Fredricks; Bauten: Cary Maurice Carter; Musik: John Dankworth; Schnitt: Paul Mason. Samuel Roeca; Kamera. Haskell stein; Kamera: Gerald Hirschfeld; Bauten: Albert Bumstead; Musik: Walter Scharf, Schnitt Stanley Regie: Don Siegel; Drehbuch: Gene L. -

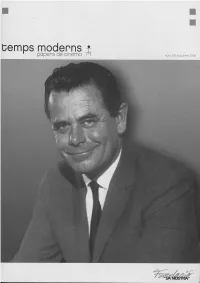

Tm 2006 N0126.Pdf

temps modems papers de cinema Edició mensual Octubre 2006 Núm. 126 Edita Centre de Cultura "SA NOSTRA" Carrer Concepció, 12 07012 Palma Telèfon 971 725 210 Fax 971 713 757 [email protected] Director Jaume Vidal Secretori Redacció Miquel Pasqual Assessorament lingüístic i traduccìons Jeroni Salom Conseil de redaccló Francisca Niell, Eva Mulet, Andreu Ramis i Josep Caries Romaguera Fotografíes Arxiu Centre de Cultura Portada: Damià Huguet davant el Café Tren de Campos Foto: M. Ballester Dlsseny maqueta / portada Santamà diseña Maquetacló Jaume Vidal i Fortesa Imprlmeix Gràfiques Planisi, SA Dipòsit Legai: PM 648-1994 Temps Moderns no comparteix, necessáriament, l'opinió deis seus col-labo- radors. Podeu trabar Temps Moderns al Centre de Cultura 'SA NOSTRA" de Maó, Eivissa, Formentera, Ciutadella i Palma; llibreria Embat, llibreria Ereso, llibres Mallorca, llibreria Espirafocs (Inca) i ais cines Portopí i Renoir. Surmari 2 Editorial 4 Memòria personal d'una visita a la Mostra de Cinema de Venezia per M. Magdalena Brotons 8 Festival Internacional de cine d'Eivissa i Formentera. Caligula protagonitza la presentació oficial per Toni Roca 10 Salvador i Alatriste, dues mirades sobre dues històries per Antoni M. Thomas 13 Jorda no era ùnicament sever per Toni Roca 15 Salvador: una pel-lfcula necessària per Joan Bover 17 Crònica de cine Algunes estrenes de l'estiu per Marti Martorell 20 Miami Vice i la buidor significativa per Pere Antoni Pons 21 El darrer estiu que vaig passar amb Gwyllyn S. Newton per Josep J. Rosselló 22 Glenn Ford. 1 de maig de 1916 - 30 d'agost de 2006 per Xavier Jimenéz 27 La mirada de l'adéu per Antoni Figuera 30 La pel-lfcula de la història L'ala trista de la Casa Bianca per Francese M. -

Following Is a Listing of Public Relations Firms Who Have Represented Films at Previous Sundance Film Festivals

Following is a listing of public relations firms who have represented films at previous Sundance Film Festivals. This is just a sample of the firms that can help promote your film and is a good guide to start your search for representation. 11th Street Lot 11th Street Lot Marketing & PR offers strategic marketing and publicity services to independent films at every stage of release, from festival premiere to digital distribution, including traditional publicity (film reviews, regional and trade coverage, interviews and features); digital marketing (social media, email marketing, etc); and creative, custom audience-building initiatives. Contact: Lisa Trifone P: 646.926-4012 E: [email protected] www.11thstreetlot.com 42West 42West is a US entertainment public relations and consulting firm. A full service bi-coastal agency, 42West handles film release campaigns, awards campaigns, online marketing and publicity, strategic communications, personal publicity, and integrated promotions and marketing. With a presence at Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Tribeca, SXSW, New York and Los Angeles film festivals, 42West plays a key role in supporting the sales of acquisition titles as well as launching a film through a festival publicity campaign. Past Sundance Films the company has represented include Joanna Hogg’s THE SOUVENIR (winner of World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic), Lee Cronin’s THE HOLE IN THE GROUND, Paul Dano’s WILDLIFE, Sara Colangelo’s THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (winner of Director in U.S. competition), Maggie Bett’s NOVITIATE -

57Th New York Film Festival September 27- October 13, 2019

57th New York Film Festival September 27- October 13, 2019 filmlinc.org AT ATTHE THE 57 57TH NEWTH NEW YORK YORK FILM FILM FESTIVAL FESTIVAL AndAnd over over 40 40 more more NYFF NYFF alums alums for for your your digitaldigital viewing viewing pleasure pleasure on onthe the new new KINONOW.COM/NYFFKINONOW.COM/NYFF Table of Contents Ticket Information 2 Venue Information 3 Welcome 4 New York Film Festival Programmers 6 Main Slate 7 Talks 24 Spotlight on Documentary 28 Revivals 36 Special Events 44 Retrospective: The ASC at 100 48 Shorts 58 Projections 64 Convergence 76 Artist Initiatives 82 Film at Lincoln Center Board & Staff 84 Sponsors 88 Schedule 89 SHARE YOUR FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE Tag us in your posts with #NYFF filmlinc.org @FilmLinc and @TheNYFF /nyfilmfest /filmlinc Sign up for the latest NYFF news and ticket updates at filmlinc.org/news Ticket Information How to Buy Tickets Online filmlinc.org In Person Advance tickets are available exclusively at the Alice Tully Hall box office: Mon-Sat, 10am to 6pm • Sun, 12pm to 6pm Day-of tickets must be purchased at the corresponding venue’s box office. Ticket Prices Main Slate, Spotlight on Documentary, Special Events*, On Cinema Talks $25 Member & Student • $30 Public *Joker: $40 Member & Student • $50 Public Directors Dialogues, Master Class, Projections, Retrospective, Revivals, Shorts $12 Member & Student • $17 Public Convergence Programs One, Two, Three: $7 Member & Student • $10 Public The Raven: $70 Member & Student • $85 Public Gala Evenings Opening Night, ATH: $85 Member & Student • $120 Public Closing Night & Centerpiece, ATH: $60 Member & Student • $80 Public Non-ATH Venues: $35 Member & Student • $40 Public Projections All-Access Pass $140 Free Events NYFF Live Talks, American Trial: The Eric Garner Story, Holy Night All free talks are subject to availability. -

Golden Glow Hollywood

YOlUMf 14 - ~IRST QUARHR 2002 ca e QUARTERLY REP Oscar brings a golden glow ba(~ to Hollywood Starts on Page 12 FRO M THE PRESIDENT We're taking the Academy Report, this periodic newsletter for members, in a new direction with this issue. We're going to publish four quarterly issues that will concentrate on providing a historical record of the Academy's activities during each quarter, and which, taken together, will constitute a calendar year annual report. Each first-quarter report will include a complete review of the annual Academy Award activities; the second quarter's will highlight the Student Academy Awards; the third will feature board elections and the financial reports from the end of the fi scal year, June 30; LAST YEAR, THE ENTRANCE TO THE we'll hear about the Nicholl Fellowship presentations PLAYERS DIRECTORY'S NEW OFFICES AT and updates in board committees and Academy staff in 1313 VINE STREET LOOKED LIKE THIS. the fourth quarter and, of course, each issue will include reports on the myriad public and educational activities The Academy Players Directory, the that take place year-round at the Academy as well as any additional information of interest to the membership. casting bible of the industry since its We'll try to include each event and we'll try to continue to be photo-intensive, because that is what inception in 1937, moved its offices in you've seemed to enjoy in the past. But we won't be very January from the headquarters building timely. We're not a newspaper and we don't have the staff or other resources to turn this thing around quickly.