Becoming a Shanghailander: a Foreign City on Chinese Soil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German-American Bund: Fifth Column Or

-41 THE GERMAN-AMERICAN BUND: FIFTH COLUMN OR DEUTSCHTUM? THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By James E. Geels, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1975 Geels, James E., The German-American Bund: Fifth Column or Deutschtum? Master of Arts (History), August, 1975, 183 pp., bibliography, 140 titles. Although the German-American Bund received extensive press coverage during its existence and monographs of American politics in the 1930's refer to the Bund's activities, there has been no thorough examination of the charge that the Bund was a fifth column organization responsible to German authorities. This six-chapter study traces the Bund's history with an emphasis on determining the motivation of Bundists and the nature of the relationship between the Bund and the Third Reich. The conclusions are twofold. First, the Third Reich repeatedly discouraged the Bundists and attempted to dissociate itself from the Bund. Second, the Bund's commitment to Deutschtum through its endeavors to assist the German nation and the Third Reich contributed to American hatred of National Socialism. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION... ....... 1 II. DEUTSCHTUM.. ......... 14 III. ORIGIN AND IMAGE OF THE GERMAN- ... .50 AMERICAN BUND............ IV. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE BUND AND THE THIRD REICH....... 82 V. INVESTIGATION OF THE BUND. 121 VI. CONCLUSION.. ......... 161 APPENDIX....... .............. ..... 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY......... ........... -

A Neighbourhood Under Storm Zhabei and Shanghai Wars

European Journal of East Asian Studies EJEAS . () – www.brill.nl/ejea A Neighbourhood under Storm Zhabei and Shanghai Wars Christian Henriot Institut d’Asie orientale, Université de Lyon—Institut Universitaire de France [email protected] Abstract War was a major aspect of Shanghai history in the first half of the twentieth century. Yet, because of the particular political and territorial divisions that segmented the city, war struck only in Chinese-administered areas. In this paper, I examine the fate of the Zhabei district, a booming industrious area that came under fire on three successive occasions. Whereas Zhabei could be construed as a success story—a rag-to-riches, swamp-to-urbanity trajectory—the three instances of military conflict had an increasingly devastating impact, from shaking, to stifling, to finally erase Zhabei from the urban landscape. This area of Shanghai experienced the first large-scale modern warfare in an urban setting. The skirmish established the pattern in which the civilian population came to be exposed to extreme forms of violence, was turned overnight into a refugee population, and lost all its goods and properties to bombing and fires. Keywords war; Shanghai; urban; city; civilian; military War is not the image that first comes to mind about Shanghai. In most accounts or scholarly studies, the city stands for modernity, economic prosperity and cultural novelty. It was China’s main financial centre, commercial hub, indus- trial base and cultural engine. In its modern history, however, Shanghai has experienced several instances of war. One could start with the takeover of the city in by the Small Sword Society and the later attempts by the Taip- ing armies to approach Shanghai. -

Regeneration and Sustainable Development in the Transformation of Shanghai

Ecosystems and Sustainable Development V 235 Regeneration and sustainable development in the transformation of Shanghai Y. Chen Department of Real estate and Housing, Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology Abstract Globalisation has had an increasing impact on the transformation of Chinese cities ever since China adopted the open door policy in 1978. Many cities in China have been struggling with the challenges of urban regeneration created by the restructuring of the traditional economy and increasing competition between cities for resources, investment and business. The closure of docks, warehouses and industries, and the deteriorating position of traditional urban centres not only created problems but also created exceptional opportunities to reshape cities and create new functions. But this kind of process also generates a series of physical, economic and social consequences for cities to tackle. In many cases the problems exceed the capacity of the local community to adapt and respond. This paper examines a number of urban regeneration projects in Shanghai, in the hope of providing a better understanding of the process of urban regeneration in China and how best to ensure that such regeneration is sustainable. The paper reassesses the aims of regeneration, the mechanisms involved in the regeneration process and its physical, economic and social consequences, discusses how to achieve sustainable development in urban regeneration and makes recommendations for future action. 1 Introduction Global market forces and increasing globalisation are clearly playing a role in the transformation of cities and towns. In most countries urban systems are experiencing dramatic changes brought about by economic restructuring, continuous mass migration and the arrival of immigrants. -

Major Development Properties

1 SHANGHAI INDUSTRIAL HOLDINGS LIMITED Set out below is a summary of the major property development projects of the Group as at 31 December 2016: Major Development Properties Pre-sold Interest Approximate Planned during Total attributable site area total GFA the year GFA sold Expected Projects of SI Type of to SI (square (square (square (square date of City Development property Development meters) meters) meters) meters) completion 1 Kaifu District, Fengsheng Residential and 90% 5,468 70,566 7,542 – Completed Changsha Building commercial 2 Chenghua District, Hi-Shanghai Commercial and 100% 61,506 254,885 75,441 151,644 Completed Chengdu residential 3 Beibei District, Hi-Shanghai Residential and 100% 30,845 74,935 20,092 – 2019 Chongqing commercial 4 Yuhang District, Hi-Shanghai Residential and 85% 74,864 230,484 81,104 – 2019 Hangzhou (Phase I) commercial 5 Yuhang District, Hi-Shanghai Residential and 85% 59,640 198,203 – – 2019 Hangzhou (Phase II) commercial 6 Wuxing District, Shanghai Bay Residential 100% 85,555 96,085 42,236 76,966 Completed Huzhou 7 Wuxing District, SIIC Garden Hotel Hotel and 100% 116,458 47,177 – – Completed Huzhou commercial 8 Wuxing District, Hurun Commercial Commercial 100% 13,661 27,322 – – Under Huzhou Plaza planning 9 Shilaoren National International Beer Composite 100% 227,675 783,500 58,387 262,459 2014 to 2018, Tourist Resort, City in phases Qingdao 10 Fengze District, Sea Palace Residential and 49% 381,795 1,670,032 71,225 – 2017 to 2021, Quanzhou commercial in phases 11 Changning District, United 88 Residential -

World Expo – Building the Foundations for Shanghai’S Future Shanghai Has Spent Over USD 95 Billion on Developments

April 2010 World Expo – Building the Foundations for Shanghai’s Future Shanghai has spent over USD 95 billion on developments. In addition, the Expo has given infrastructure investment in preparation for the Shanghai an opportunity to implement stricter 2010 World Expo. To reflect the theme of “Better environmental protection and an occasion to City, Better Life” – the Expo investments will make beautify its surroundings, making the city a more Shanghai a more integrated and more accessible attractive place to live, visit, and conduct business. city. The real legacy of the event will come from the opportunities that this new infrastructure The making of a better city creates across Shanghai in all commercial The Expo has played a central role in driving and residential property sectors. Indeed, the the infrastructure build out which is transforming foundations for a new decade of growth and Shanghai. Similar to Beijing’s experience with expansion for the city of Shanghai have been put the Olympics, the Shanghai government has in place. mobilised enormous resources to ensure that all projects are completed on time, and the city can In this paper, we seek to answer three questions: show its best face to the world. As of November • What opportunities does the 2010 World Expo 2008, the total infrastructure investment committed hold for Shanghai real estate? through 2010 was estimated at RMB 500 billion • What are the specific impacts on each (USD 73 billion). Another RMB 150 billion (USD property sector? 22 billion) were newly allocated by the Shanghai government in conjunction with the Central • What are the longer term opportunities that government’s 2008/2009 fiscal stimulus plan – part result from the city’s infrastructure investment? of the response to the global financial crisis. -

Research on Characteristics and Toughness of High Temperature Heat Wave in Jing'an District, Shanghai

E3S Web of Conferences 248, 01064 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202124801064 CAES 2021 Research on Characteristics and Toughness of High Temperature Heat Wave in Jing'an District, Shanghai Yimeng Gong1, Wei Gao1and Aiping Gou1* 1Cological Technology and Engineering, Shanghai Institute of Technology, Shanghai, 201418, China Abstract. Affected by global changes, extreme weather has become more frequent in recent years, which has had a huge impact on the urban environment. As a collection of human civilization achievements, cities have created vitality and prosperity, but with the advancement of urbanization, huge risks have emerged in the urban environment. The resilience of a city is like the immune system of a city. It is an indispensable part of urban construction. It can enable the urban environment to effectively cope with, alleviate, and eliminate risks to ensure the healthy development of the city. Starting from the definition of resilient city, this article discusses the assessment methods of resilient cities, the current construction of resilient cities, the high temperature characteristics of Jing'an District, and the spatial characteristics of Jing'an District. public security.[4]. Urban construction is a process that never stops. In the process of construction and 1 Introduction development, there are constantly influx of new things Cities are a collection of super-large spatial forms and and new information, as well as unpredictable changes civilization achievements created by mankind. Cities and risks. This is a new risk and opportunity for the have created economic prosperity and a culture of vitality, city[5]. The concept of "resilience" is to provide cities but at the same time, cities are also gestating the risks with a new perspective to deal with internal disasters and created by modern civilization. -

Shanghai Before Nationalism Yexiaoqing

East Asian History NUMBER 3 . JUNE 1992 THE CONTINUATION OF Papers on Fa r EasternHistory Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie Barme Assistant Editor Helen 1.0 Editorial Board John Clark Igor de Rachewiltz Mark Elvin (Convenor) Helen Hardacre John Fincher Colin Jeffcott W.J.F. Jenner 1.0 Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Business Manager Marion Weeks Production Oahn Collins & Samson Rivers Design Maureen MacKenzie, Em Squared Typographic Design Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the second issue of EastAsian History in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. The journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, EastAsian History Division of Pacific and Asian History, Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia Phone +61-6-2493140 Fax +61-6-2571893 Subscription Enquiries Subscription Manager, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Rates Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Politics and Power in the Tokugawa Period Dani V. Botsman 33 Shanghai Before Nationalism YeXiaoqing 53 'The Luck of a Chinaman' : Images of the Chinese in Popular Australian Sayings Lachlan Strahan 77 The Interactionistic Epistemology ofChang Tung-sun Yap Key-chong 121 Deconstructing Japan' Amino Yoshthtko-translat ed by Gavan McCormack iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing ���Il/I, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Kazai*" -a punishment -

Virtual Shanghai

ASIA mmm i—^Zilll illi^—3 jsJ Lane ( Tail Sttjaca, New Uork SOif /iGf/vrs FO, LIN CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION Draper CHINA AND THE CHINESE L; THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 House 1918 WINE ATJD~SPIRIT MERCHANTS. PROVISION DEALERS. SHIP CHANDLERS. yigents for jfidn\iratty C/jarts- HOUSE BOATS supplied with every re- quisite for Up-Country Trips. LANE CRAWFORD 8 CO., LTD., NANKING ROAD, SHANGHAI. *>*N - HOME USE RULES e All Books subject to recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books fdr home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. Limited books must be returned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. Officers should arrange for ? the return of books wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- poses they are given out for a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons Books of special value nd gift books," when the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. Readers are asked to re- port all cases of books marked or mutilated. Do not deface books by marks and writing. - a 5^^KeservaToiioT^^ooni&^by mail or cable. <3. f?EYMANN, Manager, The Leading Hotel of North China. ^—-m——aaaa»f»ra^MS«»» C UniVerS"y Ubrary DS 796.S5°2D22 Sha ^mmmmilS«u,?,?llJff travellers and — — — — ; KELLY & WALSH, Ltd. -

Vwf 2021 Program

VIRTUAL WORLD FINALS April 30th - May 29th Presented by Creative Competitions, Inc. Odyssey of the Mind Odyssey ofPledge the Mind is in the air, in my heart and everywhere. My team and I will reach together to find solutions now and forever. We are the Odyssey of the Mind. www.OMworldfinals.com Odyssey of the Mind Dear Odyssey of the Mind Team Members, Coaches, Parents, Family Members, and Volunteers, Congratulations on completing your Odyssey of the Mind problem-solving experi- ence. Our volunteer officials are excited to see the results of putting your original, creative thoughts into actual solutions. Nearly 900 teams from all over the planet are competing virtually. It is impossible to explain how touching it is to be part of our Odyssey family that supports one another through good times and bad. You are the greatest people in the world. I would like to thank the Creative Competitions, Inc. staff for continually working while abiding by health and safety guidelines. More importantly, I want to thank the 243 volunteer officials who trained for weeks and are now spending many hours watching performances so teams can be scored. There are not words to show my ap- preciation and I know the teams feel the same way. Thank you for being a part of this event. Enjoy the Virtual Creativity Festival and be sure to order a commemorative tee shirt, sweatshirt, and pin. With great admiration to you all I wish you a healthy and happy future! Sincerely, Samuel W. “Sammy” Micklus, Executive Director Odyssey of the Mind International World Finals Events May 8 Virtual Opening Ceremonies Live Broadcast, 7 pm EDT. -

Download Here

ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels PRAISE FOR REMEMBERING SHANGHAI “Highly enjoyable . an engaging and entertaining saga.” —Fionnuala McHugh, writer, South China Morning Post “Absolutely gorgeous—so beautifully done.” —Martin Alexander, editor in chief, the Asia Literary Review “Mesmerizing stories . magnificent language.” —Betty Peh-T’i Wei, PhD, author, Old Shanghai “The authors’ writing is masterful.” —Nicholas von Sternberg, cinematographer “Unforgettable . a unique point of view.” —Hugues Martin, writer, shanghailander.net “Absorbing—an amazing family history.” —Nelly Fung, author, Beneath the Banyan Tree “Engaging characters, richly detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations.” —Debra Lee Baldwin, photojournalist and author “The facts are so dramatic they read like fiction.” —Heather Diamond, author, American Aloha 1968 2016 Isabel Sun Chao and Claire Chao, Hong Kong To those who preceded us . and those who will follow — Claire Chao (daughter) — Isabel Sun Chao (mother) ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels A magnificent illustration of Nanjing Road in the 1930s, with Wing On and Sincere department stores at the left and the right of the street. Road Road ld ld SU SU d fie fie d ZH ZH a a O O ss ss U U o 1 Je Je o C C R 2 R R R r Je Je r E E u s s u E E o s s ISABEL’SISABEL’S o fie fie K K d d d d m JESSFIELD JESSFIELDPARK PARK m a a l l a a y d d y o o o o d d e R R e R R R R a a S S d d SHANGHAISHANGHAI -

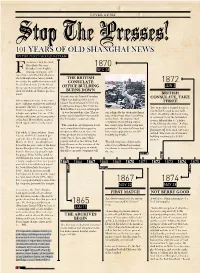

Stop the Presses!

cover story Stop The Presses! 101 YEARS OF OLD SHANGHAI NEWS BY THE THAT’S SHANGHAI TEAM ounded in 1864, the North China Daily News was 1870 Shanghai’s first English- language newspaper and DEC 28 Fone of its most influential. At a time when Shanghai was Asia’s journal- THE BRITISH ism center, the publication was noted CONSULATE 1872 for a balanced voice (for the times), strong reporters and sympathies that OFFICE BUILDING JUN 3 often lay with local Chinese predica- BURNS DOWN ments. BRITISH Shortly after the British Consulate CONSULATE, TAKE It bore witness to some of the city’s Office was built in 1849, it col- THREE most confusing, tumultuous and lurid lapsed. Reconstructed in 1852, the building standing at No. 33 on the moments. The fall of an emperor. Two years after it burned down, a Bund suffered a second catastrophe Violent struggles for power. Triad new British Consulate was built – – it was destroyed in a fire. The re- suit admirably the decimated furni- intrigue and opium. The rise of the which, thankfully, still stands today. porter seems less than impressed by ture and perhaps when everything foreign settlements and crazy parties A ceremony to lay the foundation the Consulate’s temporary digs… settles down, the impoverished at the Astor House Hotel, many of stone is delayed due to “a defect conditions of everything will be which raged until five in the morn- in the Chinese character.” A silver “The consulate and Supreme Court less conspicuous than if going into ing. trowel was ordered from Canton were moved into their respective premises of the extent of these lost, [Guangzhou] to be used, but never temporary offices yesterday, and but present appearances are suf- The whole of these archives – from arrived. -

Treaty-Port English in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai: Speakers, Voices, and Images

Treaty-Port English in Nineteenth-Century Shanghai: Speakers, Voices, and Images Jia Si, Fudan University Abstract This article examines the introduction of English to the treaty port of Shanghai and the speech communities that developed there as a result. English became a sociocultural phenomenon rather than an academic subject when it entered Shanghai in the 1840s, gradually generating various social activities of local Chinese people who lived in the treaty port. Ordinary people picked up a rudimentary knowledge of English along trading streets and through glossary references, and went to private schools to improve their linguistic skills. They used English to communicate with foreigners and as a means to explore a foreign presence dominated by Western material culture. Although those who learned English gained small-scale social mobility in the late nineteenth century, the images of English-speaking Chinese were repeatedly criticized by the literati and official scholars. This paper explores Westerners’ travel accounts, as well as various sources written by the new elite Chinese, including official records and vernacular poems, to demonstrate how English language acquisition brought changes to local people’s daily lives. I argue that treaty-port English in nineteenth-century Shanghai was not only a linguistic medium but, more importantly, a cultural agent of urban transformation. It gradually molded a new linguistic landscape, which at the same time contributed to the shaping of modern Shanghai culture. Introduction The circulation of Western languages through both textual and oral media has enormously affected Chinese society over the past two hundred years. In nineteenth-century China, the English language gradually found a social niche and influenced people’s acceptance of emerging Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review E-Journal No.