Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on the City–United Dynamic in and Around Manchester David Hand

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-space: Manchester Metropolitan University's Research Repository 12 Love thy neighbour or a Red rag to a Blue? Reflections on the City–United dynamic in and around Manchester David Hand I love Manchester United, they are great – I know because I watch them on Sky TV all the time. I once drove past Manchester on my way to a wedding … but I didn’t have time to get to a match … I love getting together with all my Man United supporter friends here in London to watch old videos of Bobby Charlton and George Best … I love all of Man United’s strips and I have bought them all for sitting in front of the telly … I once met a couple of blokes from Manchester but they supported a team called City … it’s unheard of someone from London would support City. I can’t understand why anyone would support a team that hasn’t won anything in years. Some people support a team just because they were born there – they must be mad! (MCIVTA, 2002) Any comprehensive coverage of the United phenomenon must eventually emulate the spoof Internet posting above and consider Manchester City. To an extent, the experience of City’s supporters in particular is defined (and lived) differentially in relation to what has latterly become the domineering presence of the United Other. The City–United dynamic is, therefore, a highly significant football and, indeed, social issue in Greater Manchester. -

The Haunting of LS Lowry

Societies 2013, 3, 332–347; doi:10.3390/soc3040332 OPEN ACCESS societies ISSN 2075-4698 www.mdpi.com/journal/societies Article The Haunting of L.S. Lowry: Class, Mass Spectatorship and the Image at The Lowry, Salford, UK Zoë Thompson School of Cultural Studies and Humanities, Leeds Metropolitan University, Broadcasting Place A214, Woodhouse Lane, Leeds, LS2 9EN, UK; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-0113-812-5721 Received: 4 September 2013; in revised form: 16 October 2013 / Accepted: 17 October 2013 / Published: 18 October 2013 Abstract: In a series of momentary encounters with the surface details of The Lowry Centre, a cultural venue located in Salford, Greater Manchester, UK, this article considers the fate of the image evoked by the centre’s production and staging of cultural experience. Benjamin’s notion of ‘aura’ as inimical to transformations of art and cultural spectatorship is explored, alongside its fatal incarnation in Baudrillard’s concept of ‘simulation’. L.S. Lowry, I argue, occupies the space as a medium: both as a central figure of transmission of the centre’s narrative of inclusivity through cultural regeneration, and as one who communes with phantoms: remainders of the working-class life and culture that once occupied this locale. Through an exploration of various installations there in his name, Lowry is configured as a ‘destructive character’, who, by making possible an alternative route through its spaces, refuses to allow The Lowry Centre to insulate itself from its locale and the debt it owes to its past. Keywords: aura; simulation; The Lowry; cultural regeneration; haunting; class I have been called a painter of Manchester workpeople. -

JAGUAR • ALVIS • SINGER PROGRAMME of MUSIC Selection

:» MANCHESTER CITY v BOLTON WANDERERS SATURDAY, 27th FEBRUARY i BOLTON T. St depart 12-30 1-0 1-20 1-3! 1-37 1-49 1/9 . MOSES GATE 12-33 1-2 1-25 1-33 1-40 1-52 ... 1/6 FARNWORTH & H.M. 12-35 1-4 — — 1-42 — ... 1/5 KEARSLEY 12-37 I 7 — — I -46 — .. 1/5 Return MANCHESTER VIC. 5*15 5-18 5*40 5-45 6-12 & 6*30 p.m. * TO BOLTON ONLY FULL DETAILS FROM STATIONS, OFFICES AND AGENCIES BRITISH RAILWAYS AUTOMOBILE eaaaas DISTRIBUTORS BOLTON WANDERERS COLOURS—WHITE SHIRTS, BLUE KNICKERS WINNERS OF THE 1—HANSON FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION CUP 1923, 1926 & 1929 2—BALL 3—BANKS (T) F.A. Cup Finalists 1894, 1904, 1953. 4—WHEELER 5—BARRASS 6—BELL FOOTBALL LEAGUE (NORTH) CUP 1944-45 * E LANC. CUP 1885-6, 1890-1, 1911-2, 1921-2, 1924-5, 1926-7, 1931-2, 7—HOLDEN -MOIR 9—LOFTHOUSE 10—STEVENS 11—PARRY *s *E 1933-4, 1947-8 MANCHESTER CUP 1894-5, 1905-6, 1908-9, 1920-1, 1921-2 RICHARDSON CUP 1928-9, 1930-1. WEST LANCS. CUP 1930-1, 1950-1 Referee : KICK-OFF MUM A. W. LUTY Telephone: BOLTON 800 Telegrams: "WANDERERS, BOLTON" 3-0 P.M. (Leeds) DIRECTORS: W. HAYWARD (Chairman), E. GERRARD, J.P. (Vice-Chairman), C. N. BANKS, P. DUXBURY, Aid. J. ENTWISTLE, J.P., 11- -FROGGATT 10—DALE -HENDERSON 8—GORDON 7—HARRIS *E *s *E H. WARBURTON, A. E. HARDMAN. 8—DICKINSON 5—REID 4—PHILLIPS W. RIDDING (Manager) HAROLD ABBOTTS (Secretary) *E tV *E 1953-54 SEASON 3—MANSEfcL 2—W4t#8N FUTURE EVENTS AT BURNDEN PARK: PORTSMOUTH Football League Kick-off Central League Kick-off Mar. -

Manchester 8

Manchester.qxp_Manchester 10/05/2017 10:02 Page 2 MILNER ST. LI . BARTO O . DARLEY ST. T MO EAST O MOR SS LANE X T CA X AD REYNOLDS RO N FO E . S RD AYTON GR S LEI P AC E N L A Moss V DUM AV V T THE FUR ENDIS O L W RO N R D EET ADSC S A OM E G BES N T Side IL Y E I UP E GHTON RO L T E R DO D Y E T N STR E L L UBU . D E S H REET HAYD N G H R AN N AVENUE ROWS RTO D M T A IN C B CK GH I R L A T L AVENUE A D AYLESBY ROAD N L S NO E PER P S NH E OAD S O S S O DALE C M G O A A ROAD O A R D RO T LAN D R LEI A ROAD E L A W H Old Trafford RN R L L S ROAD L ST N E T O A E U R JO R R D M SKERTON ROA D L C AYRE ST. STAYCOTT E E STREET NSON N E L S MONTONST. W H Market C BA IL O L P C R E C H D ARK BU G C STREET ROAD U H N V R Y I D AD S GREAT WESTERN STR R R ER FO N P EET R N R AD E ET N E Y TRE OA C E I T AD GS ROAD T S TA T LE O N ROA R AS A L E S KIN O N RO TON VI . -

Silva: Polished Diamond

CITY v BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 | £3.00 PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY SILVA: POLISHED DIAMOND 38008EYEU_UK_TA_MCFC MatDay_210x148w_Jan17_EN_P_Inc_#150.indd 1 21/12/16 8:03 pm CONTENTS 4 The Big Picture 52 Fans: Your Shout 6 Pep Guardiola 54 Fans: Supporters 8 David Silva Club 17 The Chaplain 56 Fans: Junior 19 In Memoriam Cityzens 22 Buzzword 58 Social Wrap 24 Sequences 62 Teams: EDS 28 Showcase 64 Teams: Under-18s 30 Access All Areas 68 Teams: Burnley 36 Short Stay: 74 Stats: Match Tommy Hutchison Details 40 Marc Riley 76 Stats: Roll Call 42 My Turf: 77 Stats: Table Fernando 78 Stats: Fixture List 44 Kevin Cummins 82 Teams: Squads 48 City in the and Offi cials Community Etihad Stadium, Etihad Campus, Manchester M11 3FF Telephone 0161 444 1894 | Website www.mancity.com | Facebook www.facebook.com/mcfcoffi cial | Twitter @mancity Chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak | Chief Executive Offi cer Ferran Soriano | Board of Directors Martin Edelman, Alberto Galassi, John MacBeath, Mohamed Mazrouei, Simon Pearce | Honorary Presidents Eric Alexander, Sir Howard Bernstein, Tony Book, Raymond Donn, Ian Niven MBE, Tudor Thomas | Life President Bernard Halford Manager Pep Guardiola | Assistants Rodolfo Borrell, Manel Estiarte Club Ambassador | Mike Summerbee | Head of Football Administration Andrew Hardman Premier League/Football League (First Tier) Champions 1936/37, 1967/68, 2011/12, 2013/14 HONOURS Runners-up 1903/04, 1920/21, 1976/77, 2012/13, 2014/15 | Division One/Two (Second Tier) Champions 1898/99, 1902/03, 1909/10, 1927/28, 1946/47, 1965/66, 2001/02 Runners-up 1895/96, 1950/51, 1988/89, 1999/00 | Division Two (Third Tier) Play-Off Winners 1998/99 | European Cup-Winners’ Cup Winners 1970 | FA Cup Winners 1904, 1934, 1956, 1969, 2011 Runners-up 1926, 1933, 1955, 1981, 2013 | League Cup Winners 1970, 1976, 2014, 2016 Runners-up 1974 | FA Charity/Community Shield Winners 1937, 1968, 1972, 2012 | FA Youth Cup Winners 1986, 2008 3 THE BIG PICTURE Celebrating what proved to be the winning goal against Arsenal, scored by Raheem Sterling. -

Planning Bulleting 7: Stadia, Football Academies and Centres of Excellence

Planning Bulletin Issue Seven March 2000 Stadia, Football Academies and Centres of Excellence Introduction The planning implications of training facilities, football academies and centres of excellence will also be This bulletin focuses on sports stadia – sporting facilities examined. New training and youth development facilities that enjoyed a boom in the 1990s both in the UK and are being planned and built by many leading football worldwide. The Millennium Stadium in Cardiff which clubs, often in green belt and countryside areas. The hosted the Rugby World Cup final in November 1999, the planning issues raised by such facilities are complex and National Stadium in Sydney which will host the Olympic will be examined by reference to two case studies. Games later this year and the new Wembley Stadium have all featured heavily in the news over the past few Stadia months. On a smaller scale, many football clubs and rugby clubs play in new stadia often located away from Sports stadia are familiar landmarks to all sports their traditional heartlands, or in stadia that have seen spectators, both the armchair and the more active major expansion and adaptation. These changes have varieties. A major stadium will often be the most happened partly to accommodate the requirements of recognisable feature of many British towns and cities, the Taylor Report on the Hillsborough Stadium disaster and of cities around the world. Indeed, it is likely that and partly as a reflection of professional sport’s more people are able to identify the Old Trafford football move ‘upmarket’. ground as a Manchester landmark than the city’s cathedral or town hall. -

7. Industrial and Modern Resource

Chapter 7: Industrial Period Resource Assessment Chapter 7 The Industrial and Modern Period Resource Assessment by Robina McNeil and Richard Newman With contributions by Mark Brennand, Eleanor Casella, Bernard Champness, CBA North West Industrial Archaeology Panel, David Cranstone, Peter Davey, Chris Dunn, Andrew Fielding, David George, Elizabeth Huckerby, Christine Longworth, Ian Miller, Mike Morris, Michael Nevell, Caron Newman, North West Medieval Pottery Research Group, Sue Stallibrass, Ruth Hurst Vose, Kevin Wilde, Ian Whyte and Sarah Woodcock. Introduction Implicit in any archaeological study of this period is the need to balance the archaeological investigation The cultural developments of the 16th and 17th centu- of material culture with many other disciplines that ries laid the foundations for the radical changes to bear on our understanding of the recent past. The society and the environment that commenced in the wealth of archive and documentary sources available 18th century. The world’s first Industrial Revolution for constructing historical narratives in the Post- produced unprecedented social and environmental Medieval period offer rich opportunities for cross- change and North West England was at the epicentre disciplinary working. At the same time historical ar- of the resultant transformation. Foremost amongst chaeology is increasingly in the foreground of new these changes was a radical development of the com- theoretical approaches (Nevell 2006) that bring to- munications infrastructure, including wholly new gether economic and sociological analysis, anthropol- forms of transportation (Fig 7.1), the growth of exist- ogy and geography. ing manufacturing and trading towns and the crea- tion of new ones. The period saw the emergence of Environment Liverpool as an international port and trading me- tropolis, while Manchester grew as a powerhouse for The 18th to 20th centuries witnessed widespread innovation in production, manufacture and transpor- changes within the landscape of the North West, and tation. -

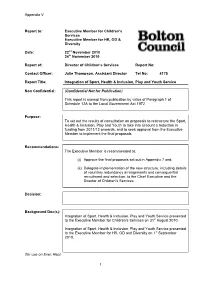

Appendix V Report To: Executive Member For

Appendix V Report to: Executive Member for Children’s Services Executive Member for HR, OD & Diversity Date: 22nd November 2010 24th November 2010 Report of: Director of Children’s Services Report No: Contact Officer: Julie Thompson, Assistant Director Tel No: 4175 Report Title: Integration of Sport, Health & Inclusion, Play and Youth Service Non Confidential: (Confidential Not for Publication) This report is exempt from publication by virtue of Paragraph 1 of Schedule 12A to the Local Government Act 1972 Purpose: To set out the results of consultation on proposals to restructure the Sport, Health & Inclusion, Play and Youth to take into account a reduction in funding from 2011/12 onwards, and to seek approval from the Executive Member to implement the final proposals. Recommendations: The Executive Member is recommended to: (i) Approve the final proposals set out in Appendix 7 and; (ii) Delegate implementation of the new structure, including details of voluntary redundancy arrangements and consequential recruitment and selection, to the Chief Executive and the Director of Children‟s Services. Decision: Background Doc(s): Integration of Sport, Health & Inclusion, Play and Youth Service presented to the Executive Member for Children‟s Services on 31st August 2010. Integration of Sport, Health & Inclusion, Play and Youth Service presented to the Executive Member for HR, OD and Diversity on 1st September 2010. (for use on Exec Rep) 1 Integration of Sport, Health & Inclusion, Play and Youth Service Review Final Proposals November 2010 Signed: Leader / Executive Member Monitoring Officer Date: Summary: Executive Report (on its own page with Appendix 1 - List of People and Organisations Consulted. -

Read Book Manchester United Supporters Book

MANCHESTER UNITED SUPPORTERS BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John White | 192 pages | 01 Dec 2011 | Carlton Books Ltd | 9781847328465 | English | London, United Kingdom Manchester United Supporters Book PDF Book IPC Media. Manchester Evening News. If you don't follow our item condition policy for returns , you may not receive a full refund. These are all qualities that every club can claim, but few have been able to articulate them so dramatically down the years. Whether you are a casual fans or hardcore one, this book summed up the history of Manchester United. BBC World Service. The best history of United book that I've read. Apr 06, Jonny Parshall rated it it was amazing Shelves: the-football , best-read Retrieved 17 December Get A Copy. Connell Sixth Form College. Pac Network. The book ends at the ending of the season which is tough to remember given United's current climate of finishing 6th in a mere 10 years later. Hewlett-Packard case study. What was surprising to me is that much of the book reads like a well crafted management guide. Cian Ciaran". The Manchester United Supporter's Book - In , the American businessman Malcolm Glazer made an attempt to buy the club, but was rebuffed by the PLC board because of the large amount of borrowing his bid would rely on. Welcome back. Retrieved 9 January For one thing not all good things start off the best, you have to work for it. In the most recent season, —, Manchester City had the fourth highest average attendance in English football and the third highest in the Premier League, with only Manchester United, Arsenal and Newcastle United drawing greater crowds. -

In Search of the Truefan: from Antiquity to the End Of

IN SEARCH OF THE TRUEFAN: POPULISM, FOOTBALL AND FANDOM IN ENGLAND FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE END OF THE TWENTlETH CENTURY Aleksendr Lim B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1997 THESIS SUBMITTED iN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History O Aleksendr Lim 2000 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 2000 Al1 rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. National Library Biblioth&que nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Weilington Ottawa ON KlAON4 WwaON K1A ON4 Canada CaMda Yaurhh Vam &lima Our W Wro&lk.nc. The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicrofom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic fonnats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT The average soccer enthusiast has a lot to feel good about with regard to the sbte of the English game as it enters the twenty-first century. -

Anfield Bicycle Club Circular

A HAPPY NEW YEAR TO ALL. ANFIELD BICYCLE CLUB FORMED MARCH 1879. PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL. Monthly Circular. Vol. XVIII. No. 203. FIXTURES FOR, JANUARY, 1923. Light op as Jan. 6. Halewood (Derby Arms) 5- 7 p.m. 8. Annual General Meeting, 25, Water Street, Liverpool, at 7 p.m. „ 13. Pulford (Grosvenor) 5-16 p.m. „ 15. Committee Meeting, 7 p.m., 25, Water Street, Liverpool. 20. Chester (Bull and Stii i-up) Musical Evon'ig.. s-27 p.m. 27. Newbargh (Red Lion) 5.40 p.m. Feb. 3. Halewood (Derby Arms) 5-57 p.m. 5. Committee Meeting. 7 p.m., 25, Water Street, Liverpool, Alternative Runs for Manchester Members. Jan. 6. Ollerton (Dun Cow) 5- 7 p.m. ., 13. Siddington (Mrs. Sam Woods) 5-16 p.m. „ 27. Lower Peover (Church House) 5.40 p.m. Feb. 3. OJlerton (Dun Cow) 5.57 p.m. Tea at 5-30 p.m. Full moon 3rd inst. The Hon. Treasurer's address is R. L. Knipe, 108, ffloseow Drive, Stoneyeroft, Liverpool, but Subscriptions ©(25/, Anfieldunder 21 10/6, under 18Bicycle5/-, Honorary aminimum Club of 10/-) and Donations (unlimited) to the Prize Fund ean be most conveniently made to any Branch of the Bank of Liverpool for eredit of the Anfield Bieyele Club, Tue Brook Braneh. Committee Notes. 94, Paterson Street, Birkenhead. New Members.—Messrs. C. Moorby and J. E. F. Sheppard have been elected to Junior Active Membership. A Musical livening is to be held at the Bull and Stirrup Hotel, Chester, on 20th January. The Committee hope that the joint meet will be even more successful than the musical evening in November. -

126431 Arena

Application Number Date of Appln Committee Date Ward 126431/FO/2020 31st Mar 2020 24th Sep 2020 Ancoats & Beswick Ward Proposal Erection of a multi-use arena (Use Class D2) with a partially illuminated external facade together with ancillary retail/commercial uses (Classes A1, A3 and A4), with highways, access, servicing, landscaping, public realm and other associated works Location Site South Of Sportcity Way, East Of Joe Mercer Way, West Of Alan Turing Way And North Of The Ashton Canal At The Etihad Campus, Manchester Applicant OVG Manchester Limited, C/o Agent Agent Miss Eve Grant, Deloitte LLP, 2 Hardman Street, Manchester, M3 3HF Description This 4.46 hectare site is used as a 500 space overspill car park for events at the Etihad stadium. The site is secured with a mesh fence on all sides and contains a number of self-seeded trees and shrubs. Its topography is relatively flat with a gentle slope from south to north before the site drops steeply down to the Ashton Canal. The site is bounded by Joe Mercer Way (an elevated pedestrian walkway connecting to the Etihad Stadium) which separates the site from the Manchester Tennis and Football Centre located further west, Alan Turing Way, a four lane road with segregated cycle lanes is to the east with the Ashton Canal and the Etihad Metrolink stop to the south. View of the site from Joe Mercer Way The site forms part of the Etihad Campus which includes the Etihad Stadium, Manchester Regional Arena, City Football Academy and the National Squash Centre. The Etihad Campus has been a focus for regeneration since it was first used to host the Manchester Commonwealth Games in 2002.