Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 31, June 2019

From the President I recently experienced a great sense of history and admiration for early Spanish and Portuguese navigators during visits to historic sites in Spain and Portugal. For example, the Barcelona Maritime Museum, housed in a ship yard dating from the 13th century and nearby towering Christopher Columbus column. In Lisbon the ‘Monument to the Discoveries’ reminds you of the achievements of great explorers who played a major role in Portugal's age of discovery and building its empire. Many great navigators including; Vasco da Gama, Magellan and Prince Henry the Navigator are commemorated. Similarly, in Gibraltar you are surrounded by military and naval heritage. Gibraltar was the port to which the badly damaged HMS Victory and Lord Nelson’s body were brought following the Battle of Trafalgar fought less than 100 miles to the west. This experience was also a reminder of the exploits of early voyages of discovery around Australia. Matthew Flinders, to whom Australians owe a debt of gratitude features in the June edition of the Naval Historical Review. The Review, with its assessment of this great navigator will be mailed to members in early June. Matthew Flinders grave was recently discovered during redevelopment work on Euston Station in London. Similarly, this edition of Call the Hands focuses on matters connected to Lieutenant Phillip Parker King RN and his ship, His Majesty’s Cutter (HMC) Mermaid which explored north west Australia in 1818. The well-known indigenous character Bungaree who lived in the Port Jackson area at the time accompanied Parker on this voyage. Other stories in this edition are inspired by more recent events such as the keel laying ceremony for the first Arafura Class patrol boat attended by the Chief of Navy. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

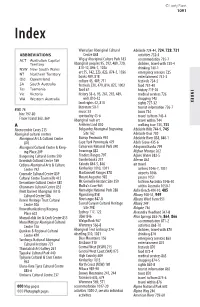

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Macquarie University Researchonline

Macquarie University ResearchOnline This is the author’s version of an article from the following conference: Walsh, Robin (2008) Pixels & Partnerships: digital publishing and co- operative scholarship in Australian and British imperial history. Digital discoveries : strategies and solutions : 29th annual conference of the Association of Technological University Libraries, (21 - 24 April 2008, Auckland) Access to the published version: http://www.iatul.org/doclibrary/public/Conf_Proceedings/2008/RWalsh 080318.doc Title Pixels & Partnerships: digital publishing and co-operative scholarship in Australian and British imperial history. Author Robin Walsh Macquarie University Library Sydney NSW 2109 Australia Contact Details [email protected] www.lib.mq.edu.au/digital/lema Abstract The efforts of libraries and archival institutions in collecting and curating dispersed collections of original letters, journals, pictorial sources, and realia/artefacts are essential contributions towards research and scholarship. Recent technological advances in digitization offer important new possibilities in the reproduction of documents and images as well as enhanced access to dispersed institutional holdings. The Lachlan & Elizabeth Macquarie Archive (LEMA) is a co-operative inter-institutional website project based at Macquarie University Library, in partnership with key Australian and UK institutions. The aim of the LEMA Project is to create a digital research gateway to the writings of the Lachlan Macquarie (1761-1824), governor of New South Wales from 1810- 1821 and his wife Elizabeth (1778-1835), and thereby assist in the study and analysis of their place in Australian and imperial history. The LEMA framework is designed to explore the personal and global contexts of the Macquaries through the use of full-text transcriptions of documentary sources, as well as contributing towards the identification and digital repatriation of personal objects associated with their lives. -

Matthew Flinders: Pathway to Fame

INTERNATIONAL HYDROGRAPHIC REVIEW VoL. 2 No. 1 {NEW SERIES) JUNE 2001 Matthew Flinders: Pathway to Fame joe Doyle Since his death many books and articles have been written about Matthew Flinders . During his life, apart from his own books, he wrote much himself, and there is a large body of contemporary correspondence concerning him in various archives in England and Australia. The bicentenary of the start of his voyage in Investigator is so important that it deserves once more, to be drawn to the atten tion of those interested in hydrography. This paper traces Matthew Flinders' early life and training as a hydrographer until July 1801 when he sailed from England in Investigator on his fateful mission to chart the little known southern continent, that land mass which had yet to be named Australia. Introduction An niversaries of two milestones of 'European ' Austral ia occur in 2001. The sig nificant event is the centenary of the formation of the Commonwealth of Australi a. It is also the bicentenary of the start of an important British voyage to complete the survey of that continent and from which the term Australia began to be accept ed as the name for the country. July 2001 is the 200th anniversary of the departure from Spithead of Investigator, a sloop' fitted out and stored for a voyage to remote parts. The vessel, under the command of Commander Matthew Flinders, Royal Navy, was bound for New South Wales, a colony established thirteen years earlier. The purpose of the voyage was to make a complete examination and survey of the coast of that island continent. -

Critical Australian Indigenous Histories

Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah (editors) Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 16 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Transgressions [electronic resource] : critical Australian Indigenous histories / editors, Ingereth Macfarlane ; Mark Hannah. Publisher: Acton, A.C.T. : ANU E Press, 2007. ISBN: 9781921313448 (pbk.) 9781921313431 (online) Series: Aboriginal history monograph Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Indigenous peoples–Australia–History. Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of–History. Colonies in literature. Australia–Colonization–History. Australia–Historiography. Other Authors: Macfarlane, Ingereth. Hannah, Mark. Dewey Number: 994 Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Secretary/ Managing Editor), Richard Baker, Gordon Briscoe, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Christine Hansen, Luise Hercus, David Johnston, Steven Kinnane, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Ann McGrath, Frances Peters- Little, Kaye Price, Deborah Bird Rose, Peter Radoll, Tiffany Shellam Editors Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah Copy Editors Geoff Hunt and Bernadette Hince Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: T Boekel, email: [email protected], tel or fax: +61 2 6230 7054 www.aboriginalhistory.org ANU E Press All correspondence should be addressed to: ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected], http://epress.anu.edu.au Aboriginal History Inc. -

Manual Pigbal 4 User Manual This Manual Provides

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries PigBal 4 user manual Version 2.6 May 2018 This publication has been compiled by Alan Skerman, Sara Willis and Brendan Marquardt of Agri-Science Queensland, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (Queensland), and Eugene McGahan, formerly of FSA Consulting. © State of Queensland, 2018 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Table of contents Table of contents .................................................................................................................. i Table of tables .................................................................................................................... -

HYDROGRAPHIC DEPARTMENT Charts, 1769-1824 Reel M406

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT HYDROGRAPHIC DEPARTMENT Charts, 1769-1824 Reel M406 Hydrographic Department Ministry of Defence Taunton, Somerset TA1 2DN National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Copied: 1987 1 HISTORICAL NOTE The Hydrographical Office of the Admiralty was created by an Order-in-Council of 12 August 1795 which stated that it would be responsible for ‘the care of such charts, as are now in the office, or may hereafter be deposited’ and for ‘collecting and compiling all information requisite for improving Navigation, for the guidance of the commanders of His Majesty’s ships’. Alexander Dalrymple, who had been Hydrographer to the East India Company since 1799, was appointed the first Hydrographer. In 1797 the Hydrographer’s staff comprised an assistant, a draughtsman, three engravers and a printer. It remained a small office for much of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, under Captain Thomas Hurd, who succeeded Dalrymple as Hydrographer in 1808, a regular series of marine charts were produced and in 1814 the first surveying vessels were commissioned. The first Catalogue of Admiralty Charts appeared in 1825. In 1817 the Australian-born navigator Phillip Parker King was supplied with instruments by the Hydrographic Department which he used on his surveying voyages on the Mermaid and the Bathurst. Archives of the Hydrographic Department The Australian Joint Copying Project microfilmed a considerable quantity of the written records of the Hydrographic Department. They include letters, reports, sailing directions, remark books, extracts from logs, minute books and survey data books, mostly dating from 1779 to 1918. They can be found on reels M2318-37 and M2436-67. -

25 International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies Volume 2

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). 25 International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies Volume 2, Number 2, 2009 Disturbing Performances of Race and Nation: King Bungaree, John Noble and Jimmy Clements Maryrose Casey Monash University Abstract This essay is an exploration of the multiple cultural performances and performative Indigenous and non-Indigenous presences competing within events and erased by dominant narratives. The performance and performativity of race, class and culture for both black and white Australians in embodied performances and in accounts as a performative source of ideological meaning-making are critical factors within cross-cultural communications. The focus of this paper is on the dynamic between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous performances and presences within the enactment and documentation of two events separated by 100 years, a nineteenth century anecdote and a twentieth century „historical‟ event. Key words: performance, Indigenous studies, cultural history Introduction Generalisations about groups of people play a fundamental role in racialised representations in relation to both the dominant groupings and the marginalised and colonised within communities and nations. This essay is an exploration of the multiple cultural performances and performative presences competing within events and manipulated in dominant accounts into generalisations. The performance and performativity of race for both black and white Australians in embodied performances and in accounts that document events are part of the ideological meaning-making framing cross-cultural communications. A crucial element of this process is that within the documentary accounts, the non-Indigenous presence and their actions are presented as a singular norm and the foregrounded focus is on Indigenous performances and actions as anomalies. -

Great Drives in New South Wales

GREAT DRIVES IN NSW Enjoy the sheer pleasure of the journey on inspirational drives in NSW. Visitors will discover views, wildlife, national parks full of natural wonders, beaches that are the envy of world and quiet country towns with stories to tell. Essential lifestyle ingredients such as wineries, great regional dining and fantastic places to spend the night cap it all off. Take your time and discover a State that is full of adventures. Discover more road trip inspiration with the Destination NSW trip and itinerary planner at: www.visitnsw.com/roadtrips The Legendary Pacific Coast Fast facts A scenic coastal drive north from Sydney to Brisbane Alternatively, fly to Newcastle, Ballina Byron or the Gold Coast and hire a car Drive length: 940km. Toowoon Bay, Central Coast Why drive it? This scenic drive takes you through some of the most striking landscapes in NSW, an almost continuous line of surf beaches, national parks and a hinterland of rolling green hills and friendly villages. The Legendary Pacific Coast has many possible themed itineraries: Coastal and Aquatic Trail Culture, Arts and Heritage Trail Food and Wine and Farmers’ Gate Journey Legendary Kids Trail National Parks and State Forests Nature Trail Legendary Surfing Safari Backpacker and Working Holiday Trail Whale-watching Trail. What can visitors do along the way? On the Central Coast, drop into a wildlife or reptile park to meet Newcastle Ocean Baths, Newcastle Australia’s native animals Stop off at Hunter Valley for cellar door wine tastings and award-winning -

Protection of Australia's Commemorative Places And

Australian Heritage Council Protection of Australia’s Commemorative Places and Monuments Report prepared for the Minister for the Environment and Energy, the Hon Josh Frydenberg MP Australian Heritage Council March 2018 Protection of Australia’s Commemorative Places and Monuments Report prepared for the Minister for the Environment and Energy, the Hon Josh Frydenberg MP © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 Protection of Australia’s Commemorative Places and Monuments is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons by Attribution 3.0 Australia licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ This report should be attributed as ‘Protection of Australia’s Commemorative Places and Monuments, Commonwealth of Australia 2018’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format: ‘© Copyright, [name of third party]’. Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

Extraordinary Sequence of Severe Weather Events in the Late-Nineteenth Century

CSIRO PUBLISHING Journal of Southern Hemisphere Earth Systems Science, 2020, 70, 252–279 Review https://doi.org/10.1071/ES19041 Extraordinary sequence of severe weather events in the late-nineteenth century Jeff Callaghan Retired. Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane, Qld., Australia. Postal address: 3/34 Macalister Road, Tweed Heads, NSW 2486, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Between 1883 and 1898, 24 intense tropical cyclones and extra tropical cyclones directly impacted on the southern Queensland and northern New South Wales coasts, with at least 200 fatalities in what was then a sparsely populated area. These events also caused record floods and rainfall, for example Brisbane City experienced its two largest ever floods over this period and Brisbane City set a 24-h rainfall record that still stands today. Additionally, a 24-h rainfall total of 907 mm occurred in a tributary of the upper Brisbane River resulting in a 15-m wall of water advancing down the river. Recent studies have shown that this part of Australia incurs the largest weather-related insurance losses. A major focus in this study is the seas these storms generated, leading to the loss of many marine craft and changes these waves brought to coastal areas. As a famous example of coastal erosion near Brisbane, the continual impacts from large waves caused a channel to form through Stradbroke Island to the open ocean forming two separate islands. Details of how this channel formed are described in relation to the storms. A climatology study of 239 Australian east coast storms that caused severe ocean damage between Brisbane and the Victorian border over the period between 1876 and February 2020 showed that 153 events occurred with a positive Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) trend and 86 events with a negative trend. -

Karla Dickens

K ARLA DICKENS B UNGAREE PAINTINGS B UNGAREE I am obsessed and warmed by the man Bungaree and his playful interaction with his new Colonial rulers. Bungaree was a man of intelligence and wit. He was flamboyant and content to play the fool because it paid off handsomely at times. He was a solid hinge swinging between black and white camps, a role possessed by few in his day. Reflecting on Broken Bay in the early 1800s, I was struck by the darkness of the times. My ‘Bungaree’ works are dark in nature because they contain black netting and somber colouring. The netting and dark tones read as an ever-present shadow lingering over Australia’s history (both visually and metaphorically), setting the atmosphere for a true, black Georgian time under blue skies. The King and The Pirates uses Bungaree’s skull to make a traditional pirates’ flag. The names of ships upon which ‘King’ Bungaree journeyed are inscribed onto the crossbones, telling the tale of him joining forces with the pirates who wore the red coats. Over his head is a ‘bump’, the currency of the time for which he was known to ask (or beg); it is reminiscent of a halo. Initiated features Bungaree’s portrait painted onto a black doily sitting atop his ‘King’ chest plate. It reads, “Boongaree Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe”. He is surrounded by ribbons emblazoned with the words “No Man’s Master, No Man’s King”. As a parody of his title “Bungaree, King of the Sydney Blacks”, I accentuated the absurdity and dark humour of this ‘King’.