New Zealand COMICS and Graphic Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CATALOGUE 2018 New Titles New Zealand Books at Their Best

CATALOGUE 2018 New Titles new zealand books at their best Birdstories CONTACT DETAILS Contents Geoff Norman Potton & Burton 98 Vickerman Street, PO Box 5128 A fascinating, in-depth account of New Zealand’s birds, which spans their New Titles Nelson, New Zealand discovery, their place in both Pākehā and Māori worlds, their survival and Birdstories Geoff Norman 3 Tel: 03 548 9009 Fax: 03 548 9456 conservation, and the illustrations and art they have inspired. Down the Bay Philip Simpson 4 Email: [email protected] www.pottonandburton.co.nz In 1872, the first instalments of Walter Buller’s A History of the Birds of New Kākāpō Alison Ballance 4 Zealand appeared. When completed, this became a landmark publishing event that Fight for the Forests Paul Bensemann 5 Customer Services Manager described the place of New Zealand’s birds in the Māori world, the first encounters Mitchell & Mitchell Peter Alsop 6 Cheryl Haltmeier Europeans had with our birds, the arguments over their classification, and provided Tel: 03 548 9009 a snapshot of their status at the time. Through Buller’s books, the rest of the Nurture Peter Alsop & Nathan Wallis 6 Email: [email protected] world got to know about New Zealand’s unusual and distinctive birds, and New We Had One of Those Too! Stephen Barnett 7 Zealanders, too, began to appreciate them. National Sales Manager Awatere Harry Broad 8 Pauline Esposito Geoff Norman’s Birdstories carries Buller’s publishing legacy through to the Raise Your Child to Read and Write Frances Adlam 9 Tel: 03 989 5051 $59.99 present day. -

Tove Jansson's Character Studies for the Moomin

INTRODUCTION by Tom Devlin, Creative Director at Drawn & Quarterly In 2011, I went to Helsinki and was lucky enough to tour Tove Jansson’s studio. She lived in the same large studio for fifty-seven years. It was easy to picture Tove there. I saw the table she used to write at; I saw the wood-burning stove she used to heat her house during the long winters; I saw the shelves and shelves of books—many her own, or her favorites by other authors, and even the hand-lettered scrapbooks her mother, Signe, made where she stored the strips she clipped from the newspaper. I saw the tiny alcove with the even tinier bed she had slept in for years. It was surprising how modest the whole place was. As far as I knew she was Finland’s greatest literary celebrity, and yet she had lived such a simple life. Of course, I should have known this before I stepped over the threshold. It’s in her books. It’s visually manifest in her comics. The Moomins them- selves live modest lives. They have many adventures but home is simple and comforting and there is nothing unnecessary. Rereading these comics just before preparing this book, it struck me just how much of Tove we get in these stories. The Moomin stories (whether in chapter book, picture book, or comic form) all have a similar quality—a quality that is rare in today’s world. There’s a distinctly carefree, individualist vibe mixed with a hint of playful cynicism, a kind of embrace-life-and-live-it-to-its- fullest-but-maybe-don’t-get-too-carried-away ethos. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

A Visual-Textual Analysis of Sarah Glidden's

BLACKOUTS MADE VISIBLE: A VISUAL-TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF SARAH GLIDDEN’S COMICS JOURNALISM _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial FulfillMent of the RequireMents for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by TYNAN STEWART Dr. Berkley Hudson, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have exaMined the thesis entitleD BLACKOUTS MADE VISIBLE: A VISUAL-TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF SARAH GLIDDEN’S COMICS JOURNALISM presented by Tynan Stewart, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. —————————————————————————— Dr. Berkley Hudson —————————————————————————— Dr. Cristina Mislán —————————————————————————— Dr. Ryan Thomas —————————————————————————— Dr. Kristin Schwain DEDICATION For my parents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My naMe is at the top of this thesis, but only because of the goodwill and generosity of many, many others. Some of those naMed here never saw a word of my research but were still vital to My broader journalistic education. My first thank you goes to my chair, Berkley Hudson, for his exceptional patience and gracious wisdom over the past year. Next, I extend an enormous thanks to my comMittee meMbers, Cristina Mislán, Kristin Schwain, and Ryan Thomas, for their insights and their tiMe. This thesis would be so much less without My comMittee’s efforts on my behalf. TiM Vos also deserves recognition here for helping Me narrow my initial aMbitions and set the direction this study would eventually take. The Missourian newsroom has been an all-consuming presence in my life for the past two and a half years. -

The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals By

Comics Aren’t Just For Fun Anymore: The Practical Use of Comics by TESOL Professionals by David Recine A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in TESOL _________________________________________ Adviser Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date _________________________________________ Graduate Committee Member Date University of Wisconsin-River Falls 2013 Comics, in the form of comic strips, comic books, and single panel cartoons are ubiquitous in classroom materials for teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL). While comics material is widely accepted as a teaching aid in TESOL, there is relatively little research into why comics are popular as a teaching instrument and how the effectiveness of comics can be maximized in TESOL. This thesis is designed to bridge the gap between conventional wisdom on the use of comics in ESL/EFL instruction and research related to visual aids in learning and language acquisition. The hidden science behind comics use in TESOL is examined to reveal the nature of comics, the psychological impact of the medium on learners, the qualities that make some comics more educational than others, and the most empirically sound ways to use comics in education. The definition of the comics medium itself is explored; characterizations of comics created by TESOL professionals, comic scholars, and psychologists are indexed and analyzed. This definition is followed by a look at the current role of comics in society at large, the teaching community in general, and TESOL specifically. From there, this paper explores the psycholinguistic concepts of construction of meaning and the language faculty. -

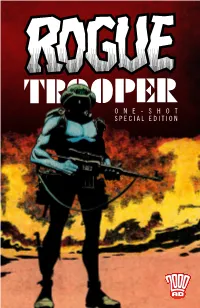

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

British Library Conference Centre

The Fifth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference 18 – 20 July 2014 British Library Conference Centre In partnership with Studies in Comics and the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics Production and Institution (Friday 18 July 2014) Opening address from British Library exhibition curator Paul Gravett (Escape, Comica) Keynote talk from Pascal Lefèvre (LUCA School of Arts, Belgium): The Gatekeeping at Two Main Belgian Comics Publishers, Dupuis and Lombard, at a Time of Transition Evening event with Posy Simmonds (Tamara Drewe, Gemma Bovary) and Steve Bell (Maggie’s Farm, Lord God Almighty) Sedition and Anarchy (Saturday 19 July 2014) Keynote talk from Scott Bukatman (Stanford University, USA): The Problem of Appearance in Goya’s Los Capichos, and Mignola’s Hellboy Guest speakers Mike Carey (Lucifer, The Unwritten, The Girl With All The Gifts), David Baillie (2000AD, Judge Dredd, Portal666) and Mike Perkins (Captain America, The Stand) Comics, Culture and Education (Sunday 20 July 2014) Talk from Ariel Kahn (Roehampton University, London): Sex, Death and Surrealism: A Lacanian Reading of the Short Fiction of Koren Shadmi and Rutu Modan Roundtable discussion on the future of comics scholarship and institutional support 2 SCHEDULE 3 FRIDAY 18 JULY 2014 PRODUCTION AND INSTITUTION 09.00-09.30 Registration 09.30-10.00 Welcome (Auditorium) Kristian Jensen and Adrian Edwards, British Library 10.00-10.30 Opening Speech (Auditorium) Paul Gravett, Comica 10.30-11.30 Keynote Address (Auditorium) Pascal Lefèvre – The Gatekeeping at -

The 2000 AD Script Book Free

FREE THE 2000 AD SCRIPT BOOK PDF Pat Mills,John Wagner,Peter Milligan,Al Ewing,Rob Williams,Dan Abnett,Emma Beeby,Gordon Rennie,Ian Edginton,Alan Grant | 192 pages | 03 Nov 2016 | Rebellion | 9781781084670 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The AD Script Book : Pat Mills : Original scripts by leading comics writers accompanied by the final art, taken from the pages of the world famous AD comic. Featuring original script drafts and the final published artwork for comparison, this is a must have for fans of AD and is an essential purchase for anyone interested in writing comics. Pat Mills is the creator and first editor of AD. He wrote Third World War for Crisis! John Wagner The 2000 AD Script Book been scripting for AD for more years than he cares to remember. The 2000 AD Script Book Ewing is a British novelist and American comic book writer, currently responsible for much of Marvel Comics' Avengers titles. He came to prominence with the 1 UK comic AD and then wrote a sequence of novels for Abaddon, of which the El Sombra books are the most celebrated, before becomiing the regular writer for Doctor Who: The Eleventh Doctor and a leading Marvel writer. He lives in York, England. John Reppion has been writing for thirteen years. He is tired. So tired. Will work for beer. By clicking 'Sign me up' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to the privacy policy and terms of use. Must redeem within 90 days. See full terms and conditions and this month's choices. Tell us what you like and we'll recommend books you'll love. -

Dark Matter #4

Cover Page DarkIssue Four Matter July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Issue Four July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Contents: Issue 4 Dark Matter Stuff 1 News & Articles 7 Gun Laws & Cosplay 7 Troopertrek 2011 8 Hugo Award Nominees 10 2010 Aurealis Awards 14 2011 Aurealis Awards to be held in Sydney again 15 2011 Ditmar Awards 16 2011 Chronos Awards 20 Renovation WorldCon 22 Iron Sky update 28 Art by Ben Grimshaw 30 Ebony Rattle as Electra, Art by Ben Grimshaw 31 The Girl in the Red Hood is Back … But She’s a Little Different 32 Launching & Gaining Velocity 34 Geek and Nerd 35 Peacemaker - A Comic Book 36 Continuum 7 Report 38 Starcraft 2 - Prae.ThorZain 46 Good Friday Appeal 50 FAQ about the writing of Machine Man, by Max Barry 65 J. Michael Straczynski says... 67 Interviews 69 Kevin J. Anderson talks to Dark Matter 69 Tom Taylor and Colin Wilson talk to Dark Matter 78 Simon Morden talks to Dark Matter 106 Paul Bedford talks to Dark Matter 115 Cathy Larsen talks to Dark Matter 131 Madeleine Roux talks to Daniel Haynes 142 Chewbacca is Coming 146 Greg Gates talks to Dark Matter 153 Richard Harland talks to Dark Matter 165 Letters 173 Anime/Animation 176 The Sacred Blacksmith Collection 176 Summer Wars 177 Evangelion 1.11 You are [not] alone 178 Evangelion 2.22 You can [not] advance 179 Book Reviews 180 The Razor Gate 180 Angelica 181 2 issue four The Map of Time 182 Die for Me 183 The Gathering 184 The Undivided 186 the twilight saga: the official illustrated guide 188 Rivers -

May 2017 New Releases

MAY 2017 NEW RELEASES GRAPHIC NOVELS • MANGA • SCI-FI/ FANTASY • GAMES VORACIOUS : FEEDING TIME Hunting dinosaurs and secretly serving them at his restaurant, Fork & Fossil, has helped Chef ISBN-13: 978-1-63229-235-3 Nate Willner become a big success. But just when he’s starting to make something of his life, Price: $17.99 ($23.99 CAN) Publisher: Action Lab he discovers that his hunting trips with Captain Jim are actually taking place in an alternate Entertainment reality – an Earth where dinosaurs evolve into Saurians, a technologically advanced race that Writer: Markisan Naso rules the far future! Some of these Saurians have mysteriously started vanishing from Artist: Jason Muhr Cretaceous City and the local authorities are hell-bent on finding who’s responsible. Nate’s Page Count: 160 world is about to collide with something much, much bigger than any dinosaur he’s ever Format: Softcover, Full Color Recommended Age: Mature roasted. Readers (ages 16 and up) Genre: Science Fiction Collecting VORACIOUS: Feeding Time #1-5, this second volume of the critically acclaimed Ship Date: 6/6/2017 series serves up a colorful bowl of characters and a platter full of sci-fi adventure, mystery and heart! SELECTED PREVIOUS VOLUMES: • Voracious: Diners, Dinosaurs & Dives (ISBN-13 978-1-63229-165-3, $14.99) PROVIDENCE ACT 1 FINAL PRINTING HC Due to overwhelming demand, we offer one final printing of the Providence Act 1 Hardcover! ISBN-13: 978-1-59291-291-9 Alan Moore’s quintessential horror series has set the standard for a terrifying reinvention of Price: $19.99 ($26.50 CAN) Publisher: Avatar Press the works of H.P. -

Hellboy in the Chapel of Moloch #1 (1 Shot) Blade of the Immortal Vol. 20 (OGN) Savage #1 (4 Issues) Soulfire Shadow Magic #0 (

H M ADVS AVENGERS V.7 DIGEST collects #24-27, $9 H ULT FF V. 11 TPB H SECRET WARS OMNIBUS collects #54-57, $13 collects #1-12 & MORE, $100 H ULT X-MEN V. 19 TPB H MMW ATLAS ERA JIM V.1 HC collects #94-97, $13 collects #1-10, $60 H MARVEL ZOMBIES TPB Hellboy in the Chapel of Moloch #1 (1 shot) H MMW X-MEN V. 7 HC collects #1-5, $16 Mike Mignola (W/A) and Dave Stewart © On the heels of the second Hellboy feature collects #67-80 LOTS MORE, $55 H MIGHTY AVENGERS V. 2 TPB film, legendary artist and Hellboy creator Mike Mignola returns to the drawing table H CIVIL WAR HC collects #7-11, $25 for this standalone adventure of the world’s greatest paranormal detective! Hellboy collects #1-7 & MORE $40 H investigates an ancient chapel in Eastern Europe where an artist compelled by some- SPIDEY BND V. 1 TPB thing more sinister than any muse has sequestered himself to complete his “life’s work.” H HALO UPRISING HC collects #546-551 & MORE, $20 collects #1-4 & SPOTLIGHT, $25 H X-MEN MESSIAH COMP TPB Blade of The Immortal vol. 20 (OGN) H HULK VOL 1 RED HULK HC collects #1-13 &MORE, $30 By Hiroaki Samura. The continuing tales of Manji and Rin. This picks up after the final collects #1-6 & WOLVIE #50, $25 H ANN CONQUEST BK 1 TPB issue #131. This is the only place to get new stories! Several old teams are reunited, a H IMM IRON FIST V.3 HC collects A LOT, $25 mind-blowing battle quickly starts and races us through most of this astonishing volume, and collects #7,15,16 & MORE, $25 H YOUNG AVENGERS PRESENTS TPB an old villain finally sees some pointed retribution at the hands of one of his prisoners! Let H INC HERCULES SI HC collects #1-6, $17 the breakout battle in the "Demon Lair" begin! collects #116-120, $20 H DAREDEVIL CRUEL & UNUSUAL TP H MI ILLIAD HC collects #106-110, $15 Spawn #185 (still on-going) collects #1-8, $25 H AMERCIAN DREAM TPB story TODD McFARLANE & BRIAN HOLGUIN art WHILCE PORTACIO & TODD H MS. -

Pdf, 742.59 KB

00:00:00 Dan McCoy Host On this episode, we discuss: Doolittle! 00:00:03 Stuart Host Why do they call him “Do little”? I think he does a lot in this movie! Wellington [Laughs.] 00:00:08 Elliott Kalan Host The—Stu, that’s exactly what I was gonna say. 00:00:11 Dan Host And it was what Audrey predicted was gonna be the gag. [Multiple people laugh.] 00:00:15 Elliott Host That is the exact thing I have written in my notes to say, Stu, for this—for this part. Ah. Two peas in a pod. 00:00:22 Music Music Light, up-tempo, electric guitar with synth instruments. 00:00:49 Dan Host Hey, everyone, and welcome to The Flop House. I’m Dan McCoy. 00:00:52 Stuart Host Oh hey there! I’m Stuart Wellington. 00:00:54 Elliott Host Top o’ the morning! Or whenever you’re listening to this—midnight? I don’t know! I’m Elliott Kalan. And Dan, who’s joining us? 00:01:01 Crosstalk Crosstalk Stuart: Yeah, Dan. Elliott: Or Stuart. 00:01:02 Dan Host Uh… 00:01:03 Elliott Host Or Dan. 00:01:04 Crosstalk Crosstalk Elliott: Or Stuart? Dan: I thought we decided on Stuart— 00:01:05 Dan Host —but I can say it. It’s—it’s David Sims, of the Blank Check podcast and he is the, uh… film reviewer for The Atlantic. And that is a—that is a big, high-toned magazine. That is, uh, that is a respected publication.