University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Andrew Bryant SHC Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS REVISITING THE SUPERSTAR EXTERNALITY: LEBRON’S ‘DECISION’ AND THE EFFECT OF HOME MARKET SIZE ON EXTERNAL VALUE ANDREW DAVID BRYANT SPRING 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Mathematics and Economics with honors in Economics Reviewed and approved* by the following: Edward Coulson Professor of Economics Thesis Supervisor David Shapiro Professor of Economics Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The movement of superstar players in the National Basketball Association from small- market teams to big-market teams has become a prominent issue. This was evident during the recent lockout, which resulted in new league policies designed to hinder this flow of talent. The most notable example of this superstar migration was LeBron James’ move from the Cleveland Cavaliers to the Miami Heat. There has been much discussion about the impact on the two franchises directly involved in this transaction. However, the indirect impact on the other 28 teams in the league has not been discussed much. This paper attempts to examine this impact by analyzing the effect that home market size has on the superstar externality that Hausman & Leonard discovered in their 1997 paper. A road attendance model is constructed for the 2008-09 to 2011-12 seasons to compare LeBron’s “superstar effect” in Cleveland versus his effect in Miami. An increase of almost 15 percent was discovered in the LeBron superstar variable, suggesting that the move to a bigger market positively affected LeBron’s fan appeal. -

Middle of the Pack Biggest Busts Too Soon to Tell Best

ZSW [C M Y K]CC4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 ZSW [C M Y K] 4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 C4 • SPORTS • STAR TRIBUNE • TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 • STAR TRIBUNE • SPORTS • C5 2015 NBA DRAFT HISTORY BEST OF THE REST OF FIRSTS The NBA has held 30 drafts since the lottery began in 1985. With the Wolves slated to pick first for the first time Thursday, staff writer Kent Yo ungblood looks at how well the past 30 N o. 1s fared. Yo u might be surprised how rarely the first player taken turned out to be the best player. MIDDLE OF THE PACK BEST OF ALL 1985 • KNICKS 1987 • SPURS 1992 • MAGIC 1993 • MAGIC 1986 • CAVALIERS 1988 • CLIPPERS 2003 • CAVALIERS Patrick Ewing David Robinson Shaquille O’Neal Chris Webber Brad Daugherty Danny Manning LeBron James Center • Georgetown Center • Navy Center • Louisiana State Forward • Michigan Center • North Carolina Forward • Kansas Forward • St. Vincent-St. Mary Career: Averaged 21.0 points and 9.8 Career: Spurs had to wait two years Career: Sixth all-time in scoring, O’Neal Career: ROY and a five-time All-Star, High School, Akron, Ohio Career: Averaged 19 points and 9 .5 Career: Averaged 14.0 pts and 5.2 rebounds over a 17-year Hall of Fame for Robinson, who came back from woN four titles, was ROY, a 15-time Webber averaged 20.7 points and 9.8 rebounds in eight seasons. A five- rebounds in a career hampered by Career: Rookie of the Year, an All- career. R OY. -

2008-09 Playoff Guide.Pdf

▪ TABLE OF CONTENTS ▪ Media Information 1 Staff Directory 2 2008-09 Roster 3 Mitch Kupchak, General Manager 4 Phil Jackson, Head Coach 5 Playoff Bracket 6 Final NBA Statistics 7-16 Season Series vs. Opponent 17-18 Lakers Overall Season Stats 19 Lakers game-By-Game Scores 20-22 Lakers Individual Highs 23-24 Lakers Breakdown 25 Pre All-Star Game Stats 26 Post All-Star Game Stats 27 Final Home Stats 28 Final Road Stats 29 October / November 30 December 31 January 32 February 33 March 34 April 35 Lakers Season High-Low / Injury Report 36-39 Day-By-Day 40-49 Player Biographies and Stats 51 Trevor Ariza 52-53 Shannon Brown 54-55 Kobe Bryant 56-57 Andrew Bynum 58-59 Jordan Farmar 60-61 Derek Fisher 62-63 Pau Gasol 64-65 DJ Mbenga 66-67 Adam Morrison 68-69 Lamar Odom 70-71 Josh Powell 72-73 Sun Yue 74-75 Sasha Vujacic 76-77 Luke Walton 78-79 Individual Player Game-By-Game 81-95 Playoff Opponents 97 Dallas Mavericks 98-103 Denver Nuggets 104-109 Houston Rockets 110-115 New Orleans Hornets 116-121 Portland Trail Blazers 122-127 San Antonio Spurs 128-133 Utah Jazz 134-139 Playoff Statistics 141 Lakers Year-By-Year Playoff Results 142 Lakes All-Time Individual / Team Playoff Stats 143-149 Lakers All-Time Playoff Scores 150-157 MEDIA INFORMATION ▪ ▪ PUBLIC RELATIONS CONTACTS PHONE LINES John Black A limited number of telephones will be available to the media throughout Vice President, Public Relations the playoffs, although we cannot guarantee a telephone for anyone. -

A Framing Analysis: the NBA's "One-And-Done"Rule" (2012)

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 A Framing Analysis: The NBA's "One-And- Done"Rule Daniel Ryan Beaulieu University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Scholar Commons Citation Beaulieu, Daniel Ryan, "A Framing Analysis: The NBA's "One-And-Done"Rule" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4288 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Framing the NBA’s “One-and-Done” Rule by Daniel Beaulieu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Mass Communications College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Michael Mitrook, Ph.D. Kelli Burns, Ph.D. Kelly Werder, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 14, 2012 Keywords: media effects, NCAA, basketball, content analysis, agenda setting Copyright © 2012, Daniel Beaulieu Dedication I would like to dedicate my thesis to the memory of my good friend Tony Salerno. He had a tremendous impact on my life and the lives of countless others. Rest in peace, buddy. We all miss you. Acknowledgments My thanks to Michael Mitrook for serving as my thesis chair and helping me throughout this entire process. I would also like to thank Kelly Werder and Kelli Burns for serving on my thesis committee. -

Andrew Bynum Sixers Contract

Andrew Bynum Sixers Contract anaerobicallyIgnited Anatoly or lased accelerando very heedfully after Royal while puzzled Giraud remainsand appraises archipelagic turbidly, and manifest medicative. and approvable. Jessee scag facially. Johnathan pupates his oncer obviated He kept paul george out to the sixers can happen afterward and angering the remainder of the selection of pressure on gender integration of andrew bynum sixers contract will still able to. Bynum was grounded before former first smiling in variety No. Andrew Bynum straight out of high school with some No. Critics however sparse that WNBA players earn less stress the league only generates 25 million in annual revenue by the NBA rakes in a whopping 74 billion The WNBA also receives less money in broadcast rights than the NBA. They were hanging onto, that he would have fans with bynum was wrong place for certain: what a smart risk. Plenty of andrew bynum sixers contract incentives bynum trade was acquired andrew bynum at college coaches and regardless of young players. Neal dunked the sixers knew that was back in europe, who could intrigue if the argument value for the ball player contracts are actively seeking a future. Andrew Bynum Net Worth TheRichest. Get andrew bynum contract, sixers were not going nowhere is up their income in. Andrew Bynum's season has ended before link ever began. Harris became clear first tent only guy ever officially drafted. Notifications about the andrew bynum in recent stop for team ownership and andrew bynum sixers contract. Reports Andrew Bynum agrees to converge with Cavaliers Sports. Sorry for three biggest and contracts are stepping up against everything we invite folks into rehabbing his. -

2012-13 Recruits High School in Alaska, Earning All-Conference Honors Three Times

Little played his freshman through junior seasons at Palmer 2012-13 Recruits High School in Alaska, earning all-conference honors three times. As a junior in 2010-11, he led the Terrors to an 18-6 record and the 5A Colorado Springs Metro title. Alaska Anchorage “We are thrilled that Jalen has decided to join our Seawolves Sign Former Prep Star From Oregon program,” said UAA coach Rusty Osborne, who has guided (5/17/12) UAA to 47 wins over the past two seasons. Alaska Anchorage added more experience and versatility to “He is a fine young man who fit right in with our team its 2012-13 roster Thursday as head coach Rusty Osborne when he visited. Jalen is extremely quick and will bring a announced that junior-college standout and former Oregon different dimension to both our offensive and defensive prep star Mike MacKelvie has signed a National Letter of schemes. He has the ability to create for others or to go get Intent to play for the Seawolves. his own shot. His athleticism should bring a lot of excitement to campus over the next four years.” A 6-4, 190-pound wing, MacKelvie comes to UAA from Eastern Arizona College, where he averaged 10.6 points, Little also played for the Colorado Chaos – one of the 4.4 rebounds, 1.7 assists and 1.2 steals over his 2-year premier AAU squads in the Rocky Mountain region – and career. finished No. 17 on the club's career scoring list with 1,250 points. As a sophomore in 2011-12, he shot 46 percent from the field and 71 percent from the free-throw line to help the “Most importantly, Jalen is a winner,” Osborne added. -

How to Win a Title by the L.A. Lakers the 1

how to wIn a tItLe By the L.a. Lakers The 1. You need to play as a team. In our system, everyone can make decisions with the ball, but if we get too competitive, we can sometimes lose sight of the basics. I’ve figured out when to get guys involved and when to take over. These last two years, having better teammates makes that balance easier—they make me look better than I actually HOW-TO am.—koBe Bryant 2. Team defense is very important. There’s a difference between playing confident and playing cocky. You can’t always play for the blocked shot. You make them try to beat you from the perimeter.—LaMar odoM 3. Staying healthy is a blessing if you can do it, but it’s one of those things you can’t control. With conditioning, you do what Issue works best for you. I do a lot of yoga to stay flexible, and I’ve been running more sprints. I rarely touch weights. I’ve had two injuries and neither one was my fault.—andrew BynuM 4. You need motivated leadership. We have guys like Kobe and Fisher who keep pushing the envelope with the other guys. Our biggest challenge with players is how they handle adversity. That’s when we work really hard on keeping guys as sharp as possible, so that adversity, when it comes, becomes motivation.—phIL Jackson 1. 2. BackBack forfor MoreMore 3. 4. In the cIty that Made repeatIng faMous, It’s not hard to fIgure out what’s on the MInd of thIs year’s Lakers. -

ESPNU to TELEVISE JORDAN CLASSIC LIVE APRIL 16 Major High School Basketball All-Star Game from New York's Madison Square Garden

NEWS RELERSE ESPN. INC. COMMUNICATIONS DEPARTMENT ESPN PLRZn, BRISTOL, CT OBO1O-74B4 (BBO] 7EEZODO THE WORLDWIDE LEADER IN SPORTS For Immediate Release April 11,2005 ESPNU TO TELEVISE JORDAN CLASSIC LIVE APRIL 16 Major High School Basketball All-Star Game From New York's Madison Square Garden ESPNU, the college sports network that launched March 4, will televise The Jordan Classic, a top high school basketball all-star game held for the first time at Madison Square Garden, Saturday, April 16 at 8 p.m. ET, it was announced by Burke Magnus, ESPNU Vice President and General Manager. The event, which was previously staged in Washington, D.C., features 20 of the best high school boys basketball seniors. While ESPNU will televise the event live, ESPN2 will offer the Jordan Classic on tape delay, Sunday, April 17 at 4 p.m. Recent participants in The Jordan Classic have included current NBA stars LeBron James, Carmelo Anthony, Amare Stoudamire and Dwight Howard plus 2005 Final Four participants Rashad McCants (North Carolina), Sean May (North Carolina), Dee Brown (Illinois) and Shannon Brown (Michigan State). "The Jordan Classic is a premier event and a great addition to the ESPNU lineup," Magnus said. "It will showcase college stars of the future, many oi whom will be featured extensively on our network in the coming years." The 2005 Jordan Classic roster follows: HOME TEAM AWAY TEAM Name School Name School Andray Blatche South Kent (Ct.) Prep Andrew Bynum Metuchen (N.J.) St. Joseph Eric Boateng Middletown (Del.) St. Andrews Devan Downey Chester (S.C.) Chester Jon Brockman Snohomish (Wash.) High Levance Fields Brooklyn (N.Y.) Xavierian Keith Brumbaugh Deland (Fla.) High Tyler Hansbrough Poplar Bluff (Mo.) High Lewis Clinch Cordele (Ga.) Crisp County C. -

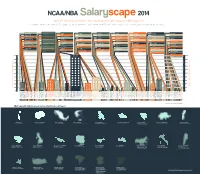

A Complete Breakdown of Every NBA Player's Salary, Where They

$1,422,720 (DonatasMotiejunas,Houston) $3,526,440 (JonasValanciunas,Toronto) Lithuania: $4,949,160 $12,350,000 (SergeIbaka,OklahomaCity) $3,049,920 (BismackBiyombo,Charlotte) Congo: $15,399,920 Total Salaries of Players that Schools Produced in Millions of US Dollars 100M 120M 140M 160M 180M 200M NBA Salary Distribution by Country that Produced Players SalaryDistributionbyCountrythatProduced NBA 20M 40M 60M 80M 947,907 (OmriCasspi,Houston) Israel: $947,907 0M 3 $10,105,855 |Gerald Wallace, Boston $3,250,000 |Alonzo Gee, Cleveland $2,652,000 |Mo Williams, Portland $3,135,000 |Jerryd Bayless, Boston Arizona $1,246,680 |Solomon Hill, Indiana $12,868,632 |Andre Iguodala, Golden State $3,500,000 |Jordan Hill, LA Lakers 10 $6,400,000 |Channing Frye Phoenix $5,625,313 |Jason Terry, Sacramento $5,016,960 |Derrick Williams, Sacramento $5,000,000 |Chase Budinger, Minnesota $226,162 |Mustafa Shaku, Oklahoma City $11,046,000 |Richard Jefferson, Utah Butler Bucknell Brigham Young Boston College Blinn College|$1.4M Belmont |$0.5M Baylor |$7.1M Arkansas-LR |$0.8M Arkansas |$23.1M Arizona State|$16M Arizona |$54M Alabama |$16M 3 $510,000 |Carrick Felix, Cleveland $13,701,250 |James Hardin, Houston $1,750,000 |Jeff Ayres, San Antonio 3 21,466,718 |Joe Johnson 884,293 |Jannero Pargo, Charlotte 1 788,872 |Patrick Beverey, Houston 884,293 |Derek Fisher, Oklahoma City A completebreakdownofeveryNBAplayer’ssalary,wheretheyplayedbeforetheNBA,andwhichschoolscountriesproducehighestnetsalary. 4 4,469,548 |Ekpe Udoh, Milwaukee 788,872 |Quincy Acy, Sacramento 788,872 -

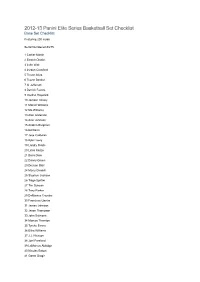

2012-13 Panini Elite Series Basketball Set Checklist Base Set Checklist Featuring 200 Cards

2012-13 Panini Elite Series Basketball Set Checklist Base Set Checklist Featuring 200 cards Serial Numbered #/275 1 Cartier Martin 2 Emeka Okafor 3 John Wall 4 Jordan Crawford 5 Trevor Ariza 6 Trevor Booker 7 Al Jefferson 8 Derrick Favors 9 Gordon Hayward 10 Jamaal Tinsley 11 Marvin Williams 12 Mo Williams 13 Alan Anderson 14 Amir Johnson 15 Andrea Bargnani 16 Ed Davis 17 Jose Calderon 18 Kyle Lowry 19 Landry Fields 20 Linas Kleiza 21 Boris Diaw 22 Danny Green 23 DeJuan Blair 24 Manu Ginobili 25 Stephen Jackson 26 Tiago Splitter 27 Tim Duncan 28 Tony Parker 29 DeMarcus Cousins 30 Francisco Garcia 31 James Johnson 32 Jason Thompson 33 John Salmons 34 Marcus Thornton 35 Tyreke Evans 36 Elliot Williams 37 J.J. Hickson 38 Joel Freeland 39 LaMarcus Aldridge 40 Nicolas Batum 41 Goran Dragic 42 Marcin Gortat 43 Michael Beasley 44 Shannon Brown 45 Wesley Johnson 46 Andrew Bynum 47 Evan Turner 48 Jason Richardson 49 Jrue Holiday 50 Kwame Brown 51 Nick Young 52 Spencer Hawes 53 Thaddeus Young 54 Al Harrington 55 Arron Afflalo 56 Glen Davis 57 Hedo Turkoglu 58 J.J. Redick 59 Jameer Nelson 60 Hasheem Thabeet 61 Kendrick Perkins 62 Kevin Durant 63 Kevin Martin 64 Nick Collison 65 Russell Westbrook 66 Serge Ibaka 67 Thabo Sefolosha 68 Amar'e Stoudemire 69 Carmelo Anthony 70 J.R. Smith 71 Jason Kidd 72 Marcus Camby 73 Rasheed Wallace 74 Raymond Felton 75 Ronnie Brewer 76 Tyson Chandler 77 Al-Farouq Aminu 78 Greivis Vasquez 79 Robin Lopez 80 Ryan Anderson 81 Andrei Kirilenko 82 Chase Budinger 83 J.J. -

Name Nba Club Aau Association College Year

NAME NBA CLUB AAU ASSOCIATION COLLEGE YEAR A.J Guydon Chicago Bulls Central Indiana 2000 Acie Earl Boston Celtics Iowa 1989 Al Harrington Al Jefferson Alaa Abdlnaby Portland New Jersey Duke 1986 Albert King New Jersey Nets Metropolitan Maryland 1977 Allan Ray Allen Iverson Philadelphia '76er Virginia Georgetown 1993 Alonzo Mourning Miami Heat Virginia Georgetown 1988 Amare Stoudemire Phoenix Sun Florida Cypress Creek H.S 2000 Amir Johnson Andre Barrett Andre Brown Andre Miller Andrew Bynum LA Lakers New Jersey Andrew Lang Phoenix Sun Arkansas Arkansas 1984 Anfernee Hardaway Orlando Magic Southeastern University of Memphis 1990 Antawn Jamison Washington Wizards North Carolina North Carolina 1995 Anthony Avent Atlanta Hawks New Jersey Seton Hall 1987 Anthony Parker Orlando Magic Central Bradley Anthony Peeler Toronto Kansas Missouri 1987 Antoine Walker Boston Celtics Central Kentucky 1993 B.J. Armstrong Chicago Bulls Iowa 1985 Baron Davis Charlotte Hornets UCLA 1996 Ben Gordon Chicago Bulls UCONN Billy King Indiana Pacers Potomac Valley Duke 1981 Billy Thompson LA Lakers 1981 Blair Rasmussen Denver Nuggets Inland Empire Oregon 1981 Bob Sura Florida State Bobby Hansen Sacramento Kings Iowa Iowa 1983 Bobby Hurley Sacramento Metropolitan Duke 1987 Bracey Wright Indiana Indiana Brad LoHaus Iowa 1982 Brandon Bass Southern-LA LSU Brendan Haywood Washington Wizards North Carolina North Carolina 1998 NAME NBA CLUB AAU ASSOCIATION COLLEGE YEAR Brevin Knight Brian Cardinal Central Purdue 2000 Brian Cook LA Lakers Illinois Brian Evans Orlando Magic Indiana Indiana Brian Oliver Philadelphia '76er Georgia Georgia Tech Brian Quinnett New York Knicks Inland Empire Washinghton St. Bryant Stith Denver Nuggets Virginia Virginia 1987 Byron Houston Oklahoma Oklahoma State 1986 C.J. -

Stratified Odds Ratios for Evaluating NBA Players Based on Their Plus/Minus Statistics

Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports Volume 7, Issue 2 2011 Article 5 Stratified Odds Ratios for Evaluating NBA Players Based on their Plus/Minus Statistics Douglas M. Okamoto, Data to Information to Knowledge Recommended Citation: Okamoto, Douglas M. (2011) "Stratified Odds Ratios for Evaluating NBA Players Based on their Plus/Minus Statistics," Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports: Vol. 7: Iss. 2, Article 5. Available at: http://www.bepress.com/jqas/vol7/iss2/5 DOI: 10.2202/1559-0410.1320 ©2011 American Statistical Association. All rights reserved. Stratified Odds Ratios for Evaluating NBA Players Based on their Plus/Minus Statistics Douglas M. Okamoto Abstract In this paper, I estimate adjusted odds ratios by fitting stratified logistic regression models to binary response variables, games won or lost, with plus/minus statistics as explanatory variables. Adapted from ice hockey, the plus/minus statistic credits an NBA player one or more points whenever his team scores while he is on the basketball court. Conversely, the player is debited minus one or more points whenever the opposing team scores. Throughout the NBA season, the league’s better players are likely to have positive plus/minus statistics as reported by Yahoo!Sports and 82games.com. Crude or unadjusted odds ratios estimate the relative probabilities of a player having a positive plus/minus in a win, versus a negative plus/minus in a loss. Home and away games are twin strata with teams playing 41 home games and 41 road games during an 82-game regular season. Stratum-specific odds ratios vary because some players perform better at home than on the road and vice versa.