A Framing Analysis: the NBA's "One-And-Done"Rule" (2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-19 Phoenix Suns Media Guide 2018-19 Suns Schedule

2018-19 PHOENIX SUNS MEDIA GUIDE 2018-19 SUNS SCHEDULE OCTOBER 2018 JANUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 SAC 2 3 NZB 4 5 POR 6 1 2 PHI 3 4 LAC 5 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON PRESEASON 7 8 GSW 9 10 POR 11 12 13 6 CHA 7 8 SAC 9 DAL 10 11 12 DEN 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:30 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON 14 15 16 17 DAL 18 19 20 DEN 13 14 15 IND 16 17 TOR 18 19 CHA 7:30 PM 6:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:30 PM 3:00 PM ESPN 21 22 GSW 23 24 LAL 25 26 27 MEM 20 MIN 21 22 MIN 23 24 POR 25 DEN 26 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 28 OKC 29 30 31 SAS 27 LAL 28 29 SAS 30 31 4:00 PM 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:30 PM 6:30 PM ESPN FSAZ 3:00 PM 7:30 PM FSAZ FSAZ NOVEMBER 2018 FEBRUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 TOR 3 1 2 ATL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4 MEM 5 6 BKN 7 8 BOS 9 10 NOP 3 4 HOU 5 6 UTA 7 8 GSW 9 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 11 12 OKC 13 14 SAS 15 16 17 OKC 10 SAC 11 12 13 LAC 14 15 16 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4:00 PM 8:30 PM 18 19 PHI 20 21 CHI 22 23 MIL 24 17 18 19 20 21 CLE 22 23 ATL 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 6:30 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 25 DET 26 27 IND 28 LAC 29 30 ORL 24 25 MIA 26 27 28 2:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:30 PM DECEMBER 2018 MARCH 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 1 2 NOP LAL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 2 LAL 3 4 SAC 5 6 POR 7 MIA 8 3 4 MIL 5 6 NYK 7 8 9 POR 1:30 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9 10 LAC 11 SAS 12 13 DAL 14 15 MIN 10 GSW 11 12 13 UTA 14 15 HOU 16 NOP 7:00 -

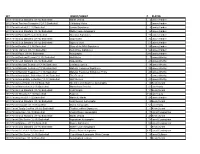

Set Insert/Subset # Player

SET INSERT/SUBSET # PLAYER 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Marks of Gold 2 James Harden 2012 Panini Timeless Treasures (12-13) Basketball Validating Marks 2 James Harden 2011 Panini Limited (11-12) Basketball Jumbo Signatures 4 James Harden 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Mother Lode Autographs 12 James Harden 2011 Panini Past and Present Basketball Breakout Signatures 16 James Harden 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Superscribe 36 James Harden 2011 Panini Gold Standard (11-12) Basketball Signs of Gold 51 James Harden 2013 Panini Prestige (13-14) Basketball Stars of the NBA Signatures 58 James Harden 2013 Panini Titanium (13-14) Basketball New Wave Signatures 56 James Harden 2013 Panini Prizm (13-14) Basketball Autographs 200 James Harden 2012 Panini Past and Present (12-13) Basketball Hall Marks 7 James Worthy 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Superscribe 28 James Worthy 2013 Panini National Treasures (13-14) Basketball Lasting Legacies 19 James Worthy 2013 Panini National Treasures (13-14) Basketball Material Treasures Signatures 29 James Worthy 2013 Panini National Treasures (13-14) Basketball Material Treasures Signatures Prime 29 James Worthy 2013 Panini Immaculate Collection (13-14) Basketball The Greatest 2 James Worthy 2013 Panini Immaculate Collection (13-14) Basketball HOF Heroes 23 James Worthy 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Sketches and Swatches Autographs 12 Kevin Durant 2012 Panini Momentum (12-13) Basketball Momentous Rookies 21 Jan Vesely 2013 Panini Gold Standard -

Open Andrew Bryant SHC Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS REVISITING THE SUPERSTAR EXTERNALITY: LEBRON’S ‘DECISION’ AND THE EFFECT OF HOME MARKET SIZE ON EXTERNAL VALUE ANDREW DAVID BRYANT SPRING 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Mathematics and Economics with honors in Economics Reviewed and approved* by the following: Edward Coulson Professor of Economics Thesis Supervisor David Shapiro Professor of Economics Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The movement of superstar players in the National Basketball Association from small- market teams to big-market teams has become a prominent issue. This was evident during the recent lockout, which resulted in new league policies designed to hinder this flow of talent. The most notable example of this superstar migration was LeBron James’ move from the Cleveland Cavaliers to the Miami Heat. There has been much discussion about the impact on the two franchises directly involved in this transaction. However, the indirect impact on the other 28 teams in the league has not been discussed much. This paper attempts to examine this impact by analyzing the effect that home market size has on the superstar externality that Hausman & Leonard discovered in their 1997 paper. A road attendance model is constructed for the 2008-09 to 2011-12 seasons to compare LeBron’s “superstar effect” in Cleveland versus his effect in Miami. An increase of almost 15 percent was discovered in the LeBron superstar variable, suggesting that the move to a bigger market positively affected LeBron’s fan appeal. -

Panini America Redemption Report November 9Th 2015

SET INSERT/SUBSET # PLAYER 2014 Panini Court Kings (14-15) Basketball Impressionist Ink 9 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Court Kings (14-15) Basketball Impressionist Ink Sapphire 9 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Paramount (14-15) Basketball Penmanship 8 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Totally Certified (14-15) Basketball Certified Competitor Autographs 2 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Totally Certified (14-15) Basketball Mirror Certified Competitor Autographs 2 Anthony Davis 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Court Kings Autographs 38 Alexey Shved 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Court Kings Autographs Gold 6 Andre Iguodala 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Court Kings Autographs Gold 38 Alexey Shved 2013 Panini Elite (13-14) Basketball Turn of the Century Signatures 75 Blake Griffin 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Rookie Autographs 244 Andre Roberson 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Rookie Autographs Platinum 244 Andre Roberson 2013 Panini Immaculate Collection (13-14) Basketball Patches Autographs 155 Alonzo Mourning 2013 Panini National Treasures (13-14) Basketball Rookie Patch Autographs 117 Alex Len 2013 Panini Preferred (13-14) Basketball Silhouettes 352 Blake Griffin 2013 Panini Prizm (13-14) Basketball Autographs 62 Blake Griffin 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Franchise Signatures Prizms Blue 7 Allan Houston 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Franchise Signatures Prizms Gold 7 Allan Houston 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Franchise Signatures Prizms Purple 7 Allan Houston 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Signatures 34 B.J. Armstrong 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Signatures Prizms Blue 34 B.J. Armstrong 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Signatures Prizms Purple 34 B.J. -

Middle of the Pack Biggest Busts Too Soon to Tell Best

ZSW [C M Y K]CC4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 ZSW [C M Y K] 4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 C4 • SPORTS • STAR TRIBUNE • TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 • STAR TRIBUNE • SPORTS • C5 2015 NBA DRAFT HISTORY BEST OF THE REST OF FIRSTS The NBA has held 30 drafts since the lottery began in 1985. With the Wolves slated to pick first for the first time Thursday, staff writer Kent Yo ungblood looks at how well the past 30 N o. 1s fared. Yo u might be surprised how rarely the first player taken turned out to be the best player. MIDDLE OF THE PACK BEST OF ALL 1985 • KNICKS 1987 • SPURS 1992 • MAGIC 1993 • MAGIC 1986 • CAVALIERS 1988 • CLIPPERS 2003 • CAVALIERS Patrick Ewing David Robinson Shaquille O’Neal Chris Webber Brad Daugherty Danny Manning LeBron James Center • Georgetown Center • Navy Center • Louisiana State Forward • Michigan Center • North Carolina Forward • Kansas Forward • St. Vincent-St. Mary Career: Averaged 21.0 points and 9.8 Career: Spurs had to wait two years Career: Sixth all-time in scoring, O’Neal Career: ROY and a five-time All-Star, High School, Akron, Ohio Career: Averaged 19 points and 9 .5 Career: Averaged 14.0 pts and 5.2 rebounds over a 17-year Hall of Fame for Robinson, who came back from woN four titles, was ROY, a 15-time Webber averaged 20.7 points and 9.8 rebounds in eight seasons. A five- rebounds in a career hampered by Career: Rookie of the Year, an All- career. R OY. -

The Case for Kevin By

The Case for Kevin By Http://DraftKevinDurant.Blogspot.Com 24 June 2007 Please send comments, questions, corrections and additional citations to: [email protected] Background : In 1984, a decision was made that altered the course of the Portland Trailblazers and left mental and emotional scars on their fan base that exist to this day. That decision, of course, was to draft Kentucky center Sam Bowie with the team’s #2 pick in the NBA draft, leaving Michael Jordan, who became the undisputed greatest basketball player in the history of the world, to the Chicago Bulls at #3. In a recent interview, Houston Rockets President Ray Patterson defended the Blazers’ decision to draft Bowie, stating, “Anybody who says they would have taken Jordan over Bowie is whistling in the dark. Jordan just wasn't that good.”1 “Jordan just wasn’t that good? ” Reading that quote more than twenty years later, it’s almost impossible to fathom that there existed a day in which “basketball people,” the executive who today are paid millions of dollars to judge the relative mental and athletic skills of teenagers, could not determine that the mythic Michael Jordan was, and would be, a better basketball player than the infamous Sam Bowie. Many things have changed since 1984: AAU youth basketball allows fans to watch players at younger ages, the internet disperses grainy street court video across the world, the NBA has its own television network making famous any and all of its players, mathematical algorithms are used by executives to aid in personnel judgment, and scouts, writers, journalists and bloggers are able to weigh the relative merits of players in ways never thought possible in 1984. -

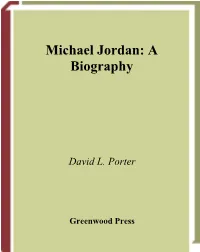

Michael Jordan: a Biography

Michael Jordan: A Biography David L. Porter Greenwood Press MICHAEL JORDAN Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Tiger Woods: A Biography Lawrence J. Londino Mohandas K. Gandhi: A Biography Patricia Cronin Marcello Muhammad Ali: A Biography Anthony O. Edmonds Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography Roger Bruns Wilma Rudolph: A Biography Maureen M. Smith Condoleezza Rice: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Arnold Schwarzenegger: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz and Michael Blitz Billie Holiday: A Biography Meg Greene Elvis Presley: A Biography Kathleen Tracy Shaquille O’Neal: A Biography Murry R. Nelson Dr. Dre: A Biography John Borgmeyer Bonnie and Clyde: A Biography Nate Hendley Martha Stewart: A Biography Joann F. Price MICHAEL JORDAN A Biography David L. Porter GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES GREENWOOD PRESS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT • LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, David L., 1941- Michael Jordan : a biography / David L. Porter. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies, ISSN 1540–4900) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33767-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-313-33767-5 (alk. paper) 1. Jordan, Michael, 1963- 2. Basketball players—United States— Biography. I. Title. GV884.J67P67 2007 796.323092—dc22 [B] 2007009605 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by David L. Porter All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007009605 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33767–3 ISBN-10: 0–313–33767–5 ISSN: 1540–4900 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

The Rebirth of the NBA - Well, Almost: an Analysis of the Maurice Clarett Decision and Its Impact on the National Basketball Association

Volume 108 Issue 3 Article 13 April 2006 The Rebirth of the NBA - Well, Almost: An Analysis of the Maurice Clarett Decision and Its Impact on the National Basketball Association Kevin J. Cimino West Virginia University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Kevin J. Cimino, The Rebirth of the NBA - Well, Almost: An Analysis of the Maurice Clarett Decision and Its Impact on the National Basketball Association, 108 W. Va. L. Rev. (2006). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol108/iss3/13 This Student Work is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cimino: The Rebirth of the NBA - Well, Almost: An Analysis of the Maurice THE REBIRTH OF THE NBA - WELL, ALMOST: AN ANALYSIS OF THE MAURICE CLARETT DECISION AND ITS IMPACT ON THE NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 832 I. OVERVIEW OF APPLICABLE ANTITRUST LAW .............................................. 835 A. The Sherman Act .................................................................... 835 B. Nonstatutory Exemption ......................................................... 836 C. The Eighth Circuit's Interpretation of the Nonstatutory Exemption in Mackey v. National Football League ............... 838 D. The United States Supreme Court's Most Recent Treatment of the Nonstatutory Exemption: Brown v. Pro Football, Inc ...... 839 E. Second Circuit Cases Construing the Nonstatutory Exemption ........................................................ -

Illegal Defense: the Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2004 Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael McCann University of New Hampshire School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Collective Bargaining Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Sports Management Commons, Sports Studies Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Unions Commons Recommended Citation Michael McCann, "Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft," 3 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L. J.113 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 3 Va. Sports & Ent. L.J. 113 2003-2004 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 10 13:54:45 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1556-9799 Article Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael A. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IMPLICIT ATTITUDES AS PRECURSORS OF SPORT CONSUMER BEHAVIOR: PREDICTIVE AND INCREMENTAL VALIDITY OF DUAL ATTITUDE IN ATHLETE ENDORSEMENT EVALUATION By YONGHWAN CHANG A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Yonghwan Chang To Il Rang, Chloe & Claire ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Numerous people have provided invaluable support for the completion of my dissertation. First of all, I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the committee chairperson, Dr. Yong Jae Ko. I am truly indebted for his advice, encouragement, tremendous support, and opportunities he provided for last years at the University of Florida. I cannot find words to express my wholehearted appreciation for him. I would also thank other committee members, Drs. Michael Sagas, Brian Mills, and Chris Janiszewski, who have been really encouraging and supportive. I am also very grateful that I have worked with the best colleagues at the University of Florida and the College of Health and Human Performance. Most importantly, I deeply thank my family and friends. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 LIST OF TABLES ...........................................................................................................................9 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................10 -

The Effect of Early Entry to the NBA

The Effect of Early Entry to the NBA An Examination of the 19-Year-Old Age Minimum and the Choice between On-The- Job Training and Schooling for NBA Prospects Nick Sugai Senior Honors Thesis Amherst College Thesis Advisor: Prof. Rivkin 2010 Sugai 2 Table Of Contents 1. Introduction 3 i. Issue and Historical Background 3 ii. Age Minimum Incentives 7 2. Literature Review 9 3. Choice Framework 12 4. Conceptual Framework 16 5. Empirical Model 22 6. Data 29 7. Results 35 8. Conclusion 47 Sugai 3 PART 1: INTRODUCTION I. Issue and Historical Background Several decades ago, players entering the NBA directly from high school were few and far between. Moses Malone famously made the jump from high school in 1974, and more recently Shawn Kemp experienced early success after joining the NBA in 1989 without college basketball experience. In 1995, however, Kevin Garnett was selected fifth overall in the NBA draft and sparked the modern trend of bypassing college. Part of the reason behind his selection directly from high school was the new NBA collective bargaining agreement that forced rookies to sign under a slotted pay scale for three years rather than negotiate contracts. As Groothuis, Hill, and Perri (2007) suggest, teams could now pay players beneath their marginal revenue product for their first few years in the league and recoup any costs spent for on-the-job training and development.1 Sports journalists jumped on Kevin Garnett’s success story, and standout high school players began to follow his lead after witnessing his immediate impact in the league. -

Study Suggests Racial Bias in Calls by NBA Referees 4 NBA, Some Players

Report: Study suggests racial bias in calls by NBA referees 4 NBA, some players dismiss study on racial bias in officiating 6 SUBCONSCIOUS RACISM DO NBA REFEREES HAVE RACIAL BIAS? 8 Study suggests referee bias ; NOTEBOOK 10 NBA, some players dismiss study that on racial bias in officiating 11 BASKETBALL ; STUDY SUGGESTS REFEREE BIAS 13 Race and NBA referees: The numbers are clearly interesting, but not clear 15 Racial bias claimed in report on NBA refs 17 Study of N.B.A. Sees Racial Bias In Calling Fouls 19 NBA, some players dismiss study that on racial bias in officiating 23 NBA calling foul over study of refs; Research finds white refs assess more penalties against blacks, and black officials hand out more to... 25 NBA, Some Players Dismiss Referee Study 27 Racial Bias? Players Don't See It 29 Doing a Number on NBA Refs 30 Sam Donnellon; Are NBA refs whistling Dixie? 32 Stephen A. Smith; Biased refs? Let's discuss something serious instead 34 4.5% 36 Study suggests bias by referees NBA 38 NBA, some players dismiss study on racial bias in officiating 40 Position on foul calls is offline 42 Race affects calls by refs 45 Players counter study, say refs are not biased 46 Albany Times Union, N.Y. Brian Ettkin column 48 The Philadelphia Inquirer Stephen A. Smith column 50 AN OH-SO-TECHNICAL FOUL 52 Study on NBA refs off the mark 53 NBA is crying foul 55 Racial bias? Not by refs, players say 57 CALL BIAS NOT HARD TO BELIEVE 58 NBA, players dismiss study on racial bias 60 NBA, players dismiss study on referee racial bias 61 Players dismiss