The Booth, the Floor and the Wall Dance Music and the Fear of Falling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chris Billam-Smith

MEET THE TEAM George McMillan Editor-in-Chief [email protected] Remembrance day this year marks 100 years since the end of World War One, it is a time when we remember those who have given their lives fighting in the armed forces. Our features section in this edition has a great piece on everything you need to know about the day and how to pay your respects. Elsewhere in the magazine you can find interviews with The Undateables star Daniel Wakeford, noughties legend Basshunter and local boxer Chris Billam Smith who is now prepping for his Commonwealth title fight. Have a spooky Halloween and we’ll see you at Christmas for the next edition of Nerve Magazine! Ryan Evans Aakash Bhatia Zlatna Nedev Design & Deputy Editor Features Editor Fashion & Lifestyle Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Silva Chege Claire Boad Jonathan Nagioff Debates Editor Entertainment Editor Sports Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3 ISSUE 2 | OCTOBER 2018 | HALLOWEEN EDITION FEATURES 6 @nervemagazinebu Remembrance Day: 100 years 7 A whitewashed Hollywood 10 CONTENTS /Nerve Now My personal experience as an art model 13 CONTRIBUTORS FEATURES FASHION & LIFESTYLE 18 Danielle Werner Top tips for stress-free skin 19 Aakash Bhatia Paris Fashion Week 20 World’s most boring Halloween costumes 22 FASHION & LIFESTYLE Best fake tanning products 24 Clare Stephenson Gracie Leader DEBATES 26 Stephanie Lambert Zlatna Nedev Black culture in UK music 27 DESIGN Do we need a second Brexit vote? 30 DEBATES Ryan Evans Latin America refugee crisis 34 Ella Smith George McMillan Hannah Craven Jake Carter TWEETS FROM THE STREETS 36 Silva Chege James Harris ENTERTAINMENT 40 ENTERTAINMENT 7 Emma Reynolds The Daniel Wakeford Experience 41 George McMillan REMEMBERING 100 YEARS Basshunter: No. -

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 2 Live Crew Sports Weekend 2nd II None If You Want It 2nd II None Classic 220 2Pac Changes 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac I Get Around / Keep Ya Head Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 702. Where My Girls At 7L & Esoteric The Soul Purpose A Taste Of Honey A Taste Of Honey A Tribe Called Quest Unreleased & Unleashed Above The Law Untouchable Abyssinians Best Of The Abyssinians Abyssinians Satta Adele 21. Adele 21. Admiral Bailey Punanny ADOR Let It All Hang Out African Brothers Hold Tight (colorido) Afrika Bambaataa Renegades Of Funk Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Agallah You Already Know Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Akon Konvicted Akrobatik The EP Akrobatik Absolute Value Al B. Sure Rescue Me Al Green Greatest Hits Al Johnson Back For More Alexander O´Neal Criticize Alicia Keys Fallin Remix Alicia Keys As I Am (vinil colorido) Alicia Keys A Woman´s Worth Alicia Myers You Get The Best From Me Aloe Blacc Good Things Aloe Blacc I Need A Dollar Alpha Blondy Cocody Rock Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (vinil colorido) Alton Ellis Mad Mad Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Anita Baker Rapture Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Augustus Pablo King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown Augustus Pablo In Fine Style Augustus Pablo This Is Augustus Pablo Augustus Pablo Dubbing With The Don Augustus Pablo Skanking Easy AZ Sugar Hill B.G. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

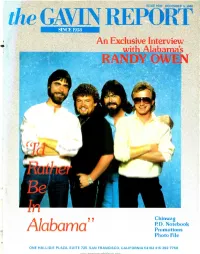

The GAVIN REP SINCE 1958 an Exclusive Interview 'S

IS3UE 1635 OECEIWBEF 5, 1986 the GAVIN REP SINCE 1958 An Exclusive Interview 's Chinwag P.D. Notebook Alabama" Promotions Photo File ONE HALLIDIE PLAZA, SUITE 725 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA E4102 4`5.392.7750 www.americanradiohistory.com P A U L S I M O N G R A C E L A N D ©1986 Warner Bros. Records Inc. From the album Graceland COEC CIO FIATE YOVFR PLAYLIST WITH THESE FOVFR SINGLES. mowÁ F.MVY R1 :AT HErn T oft!1"11:.:.;i From the album Rod Stewart www.americanradiohistory.com the GAVIN REPORT Editor: Dave Sholin TOP 40 CHART Reports accepted Mondays at SAM through 11AM Wednesdays Station Reporting Phone (415)392 -7750 MOST ADDED TW 2 2 1 BRUCE HORNSBY & THE RANGE - The Way It Is (RCA) 5 3 2 WANG CHUNG - Have Fun Tonight (Geffen) 8 4 3 BANGLES - Walk Like An Egyptian (Columbia) 1 1 4 Huey Lewis & The News - Hip To Be Square (Chrysalis) 10 7 5 PRETENDERS - Don't Get Me Wrong ( Sire/Warner Bros.) 14 8 6 DURAN DURAN - Notorious (Capitol) 15 12 7 SURVIVOR - Is This Love (Scotti Bros.) A BOSTON 13 11 8 HOWARD JONES - You Know I Love You...Don't You? (Elektra) Were Ready 17 13 9 GENESIS - Land Of Confusion (Atlantic) (MCA) 24 17 10 BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN- War (Columbia) 120 Adds 19 15 11 J OBBIE NEVIL - C'est La Vie (Manhattan) 3 5 12 Peter Cetera & Amy Grant - The Next Time I Fall In Love (Full Moon/W.B.) 27 19 13 GREGORY ABBOTT - Shake You Down (Columbia) LIONEL RICHIE 12 14 14 Billy Idol - To Be A Lover (Chrysalis) Ballerina Girl 25 22 15 GLASS TIGER - Someday (Manhattan) (Motown) 21 18 16 BILLY OCEAN - Love Is Forever (Jive/Arista) 70 Adds 22 20 17 BEN E. -

L'hantologie Résiduelle, L'hantologie Brute, L'hantologie Traumatique*

Playlist Society Un dossier d’Ulrich et de Benjamin Fogel V3.00 – Octobre 2013 L’hantologie Trouver dans notre présent les traces du passé pour mieux comprendre notre futur Sommaire #1 : Une introduction à l’hantologie #2 : L’hantologie brute #3 : L’hantologie résiduelle #4 : L’hantologie traumatique #5 : Portrait de l’artiste hantologique : James Leyland Kirby #6 : Une ouverture (John Foxx et Public Service Broadcasting) L’hantologie - Page | 1 - Playlist Society #1 : Une introduction à l’hantologie Par Ulrich abord en 2005, puis essentiellement en 2006, l’hantologie a fait son D’ apparition en tant que courant artistique avec un impact particulièrement marqué au niveau de la sphère musicale. Évoquée pour la première fois par le blogueur K-Punk, puis reprit par Simon Reynolds après que l’idée ait été relancée par Mike Powell, l’hantologie s’est imposée comme le meilleur terme pour définir cette nouvelle forme de musique qui émergeait en Angleterre et aux Etats-Unis. A l’époque, cette nouvelle forme, dont on avait encore du mal à cerner les contours, tirait son existence des liens qu’on pouvait tisser entre les univers de trois artistes : Julian House (The Focus Group / fondateur du label Ghost Box), The Caretaker et Ariel Pink. C’est en réfléchissant sur les dénominateurs communs, et avec l’aide notamment de Adam Harper et Ken Hollings, qu’ont commencé à se structurer les réflexions sur le thème. Au départ, il s’agissait juste de chansons qui déclenchaient des sentiments similaires. De la nostalgie qu’on arrive pas bien à identifier, l’impression étrange d’entendre une musique d’un autre monde nous parler à travers le tube cathodique, la perception bizarre d’être transporté à la fois dans un passé révolu et dans un futur qui n’est pas le nôtre, voilà les similitudes qu’on pouvait identifier au sein des morceaux des trois artistes précités. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

ACRONYM 11 - Round 8

ACRONYM 11 - Round 8 1. Kyle Schwarber tore his ACL in 2016 on a play of this type by Jean Segura. Alcides Escobar performed this action in his team's first at bat of the 2015 World Series. A unique one of these actions by Roberto Clemente occurred with the bases loaded and in walk-off fashion. This type of play is scored differently if a (*) defensive error occurs. In 2017, one of these plays by Byron Buxton took just 13.85 seconds after he hit a ball over A.J. Pollock's head. For 10 points, name this type of four-base hit in which the ball remains in play. ANSWER: inside-the-park home runs (or in the park home runs or similar; prompt on "home run") <Nelson> 2. As a child, this character used the mnemonic 'CALM' to control her anger, in which the 'C' stands for "cheese." A love interest of this character creates a graphic novel depicting their hypothetical life together. This woman becomes ordained to officiate the wedding of her parents, one of whom works with this woman on the (*) telenovela The Passion of Santos. During a routine checkup, this Venezuelan girl's doctor makes a profound mistake that results in her seemingly impossible pregnancy. Gina Rodriguez plays, for 10 points, what TV "virgin"? ANSWER: Jane (Gloriana) Villanueva (accept Jane the Virgin; prompt on "Villanueva") <Nelson> 3. The 1983 film Blue Thunder is titled for one of these objects. During the making of a film version of The Twilight Zone, a falling one of these things killed Vic Morrow and two child actors. -

Hall of Fame Andy Partridge

Hall of Fame Andy Partridge Andrew John Partridge (born 11 November 1953) is an English singer, songwriter, guitarist, and record producer from Swindon. He is best known for co-founding the rock band XTC, in which he served as the group's primary songwriter and vocalist. While the band was formed as an early punk rock group, Partridge's music drew heavily from British Invasion songwriters, and his style gradually shifted to more traditional pop, often with pastoral themes. The band's only British top 10 hit, "Senses Working Overtime" (1982), was written by Partridge. In addition to his work with XTC, Partridge has released one solo album on Virgin Records in 1980 called Take Away / The Lure of Salvage. He has also collaborated (as performer, writer or record producer) with recording artists, including Martin Newell, with whom he recorded and produced an album in 1993 entitled The Greatest Living Englishman released in Japan as a duo album. Partridge was producer for the English band Blur during the recording of Modern Life Is Rubbish (1993). He was replaced by Stephen Street at the insistence of their record label, Food. According to Partridge he was unpaid for the sessions and received his expenses only. Partridge also wrote four songs for Disney's version of James and the Giant Peach (1996) but was replaced by Randy Newman when he could not get Disney to offer him "an acceptable deal". In the 2000s, Partridge began releasing demos of his songs under his own name in The Official Fuzzy Warbles Collector's Album and the Fuzzy Warbles album series on his APE House record label. -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: the 1970S: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Key People Allman

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: The 1970s: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Key People Allman Brothers Band: Most important southern rock band of the late 1960s and early 1970s who reconnected the generative power of the blues to the mainstream of rock music. Barry White (1944‒2004): Multitalented African American singer, songwriter, arranger, conductor, and producer who achieved success as an artist in the 1970s with his Love Unlimited Orchestra; perhaps best known for his full, deep voice. Carlos Santana (b. 1947): Mexican-born rock guitarist who combined rock, jazz, and Afro-Latin elements on influential albums like Abraxas. Carole King (b. 1942): Singer-songwriter who recorded influential songs in New York’s Brill Building and later recorded the influential album Tapestry in 1971. Charlie Rich (b. 1932): Country performer known as the “Silver Fox” who won the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year award in 1974 for his song “The Most Beautiful Girl.” Chic: Disco group who recorded the hit “Good Times.” Chicago: Most long-lived and popular jazz rock band of the 1970s, known today for anthemic love songs such as “If You Leave Me Now” (1976), “Hard to Say I’m Sorry” (1982), and “Look Away” (1988). David Bowie (1947‒2016): Glam rock pioneer who recorded the influential album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars in 1972. Dolly Parton (b. 1946): Country music star whose flexible soprano voice, songwriting ability, and carefully crafted image as a cheerful sex symbol combined to gain her a loyal following among country fans. -

Turntablism and Audio Art Study 2009

TURNTABLISM AND AUDIO ART STUDY 2009 May 2009 Radio Policy Broadcasting Directorate CRTC Catalogue No. BC92-71/2009E-PDF ISBN # 978-1-100-13186-3 Contents SUMMARY 1 HISTORY 1.1-Defintion: Turntablism 1.2-A Brief History of DJ Mixing 1.3-Evolution to Turntablism 1.4-Definition: Audio Art 1.5-Continuum: Overlapping definitions for DJs, Turntablists, and Audio Artists 1.6-Popularity of Turntablism and Audio Art 2 BACKGROUND: Campus Radio Policy Reviews, 1999-2000 3 SURVEY 2008 3.1-Method 3.2-Results: Patterns/Trends 3.3-Examples: Pre-recorded music 3.4-Examples: Live performance 4 SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM 4.1-Difficulty with using MAPL System to determine Canadian status 4.2- Canadian Content Regulations and turntablism/audio art CONCLUSION SUMMARY Turntablism and audio art are becoming more common forms of expression on community and campus stations. Turntablism refers to the use of turntables as musical instruments, essentially to alter and manipulate the sound of recorded music. Audio art refers to the arrangement of excerpts of musical selections, fragments of recorded speech, and ‘found sounds’ in unusual and original ways. The following paper outlines past and current difficulties in regulating these newer genres of music. It reports on an examination of programs from 22 community and campus stations across Canada. Given the abstract, experimental, and diverse nature of these programs, it may be difficult to incorporate them into the CRTC’s current music categories and the current MAPL system for Canadian Content. Nonetheless, turntablism and audio art reflect the diversity of Canada’s artistic community. -

Mahogany Rush, Seattle Center Coliseum

CONCERTS 1) KISS w/ Cheap Trick, Seattle Center Coliseum, 8/12/77, $8.00 2) Aerosmith w/ Mahogany Rush, Seattle Center Coliseum,, 4/19/78, $8.50 3) Angel w/ The Godz, Paramount NW, 5/14/78, $5.00 4) Blue Oyster Cult w/ UFO & British Lions, Hec Edmondson Pavilion, 8/22/78, $8.00 5) Black Sabbath w/ Van Halen, Seattle Center Arena, 9/23/78, $7.50 6) 10CC w/ Reggie Knighton, Paramount NW, 10/22/78, $3.50 7) Rush w/ Pat Travers, Seattle Center Coliseum, 11/7/78, $8.00 8) Queen, Seattle Center Coliseum, 12/12/78, $8.00 9) Heart w/ Head East & Rail, Seattle Center Coliseum, 12/31/78, $10.50 10) Alice Cooper w/ The Babys, Seattle Center Coliseum, 4/3/79, $9.00 11) Jethro Tull w/ UK, Seattle Center Coliseum, 4/10/79, $9.50 12) Supertramp, Seattle Center Coliseum, 4/18/79, $9.00 13) Yes, Seattle Center Coliseum, 5/8/79, $10.50 14) Bad Company w/ Carillo, Seattle Center Coliseum, 5/30/79, $9.00 15) Triumph w/ Ronnie Lee Band (local), Paramount NW, 6/2/79, $6.50 16) New England w/ Bighorn (local), Paramount NW, 6/9/79, $3.00 17) Kansas w/ La Roux, Seattle Center Coliseum, 6/12/79, $9.00 18) Cheap Trick w/ Prism, Hec Edmondson Pavilion, 8/2/79, $8.50 19) The Kinks w/ The Heaters (local), Paramount NW, 8/29/79, $8.50 20) The Cars w/ Nick Gilder, Hec Edmondson Pavilion, 9/21/79, $9.00 21) Judas Priest w/ Point Blank, Seattle Center Coliseum, 10/17/79, Free – KZOK giveaway 22) The Dishrags w/ The Look & The Macs Band (local), Masonic Temple, 11/15/79, $4.00 23) KISS w/ The Rockets, Seattle Center Coliseum, 11/21/79, $10.25 24) Styx w/ The Babys, Seattle